AC Motors vs. DC Motors: Which is More Efficient and Why?

Every design engineer, procurement manager, and system integrator eventually faces a fundamental choice that echoes through the entire lifecycle of a product: AC or DC motor? The question often boils down to efficiency. You’re tasked with maximizing performance, minimizing energy consumption, and keeping operational costs in check. If you’ve ever found yourself weighing the trade-offs between different motor technologies and their impact on performance and your budget, you’re in exactly the right place.

The simple answer is that the question itself has evolved. A decade ago, the comparison was simpler. But today, asking “Are AC motors more efficient than DC motors?” is like asking if a truck is better than a car. The real answer is, “It depends entirely on the type of truck, the type of car, and what you need it to do.”

This guide will serve as your engineering partner, breaking down the nuances of motor efficiency. We’ll move beyond the outdated debate of simple brushed DC versus standard AC induction and dive into the modern landscape, comparing today’s high-performance AC motors with VFDs against the true efficiency champions: electronically commutated motors like BLDC and PMSM. We’ll explore the physics behind energy loss, guide you through the options, and empower you to make the most informed decision for your application.

What We’ll Cover

- Understanding Electric Motor Efficiency and Losses: A look at the fundamental principles governing why motors waste energy.

- The Landscape of DC Motors: From traditional brushed designs to modern, high-efficiency brushless technology.

- The Landscape of AC Motors: Exploring the industrial workhorse—the induction motor—and its high-performance synchronous cousins.

- Direct Comparison: AC vs. DC Motor Efficiency Factors: A head-to-head analysis of performance under various conditions.

- Modern Trends and The Verdict on Efficiency: A clear summary of which motor type wins in today’s technological environment.

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Answering your most common questions.

Understanding Electric Motor Efficiency and Losses

Before we compare motor types, let’s establish what we’re actually measuring. At its core, motor efficiency is a simple ratio:

Efficiency (%) = (Mechanical Power Output / Electrical Power Input) x 100

In a perfect world, this would be 100%. But in reality, every motor loses some energy during the conversion from electrical to mechanical power. These losses manifest primarily as heat, which not only wastes electricity but can also reduce the motor’s lifespan. Understanding where these losses come from is the key to understanding efficiency.

Think of these losses like small leaks in a plumbing system. Even if the main pipe is large, enough tiny leaks will significantly reduce the water pressure at the other end. In a motor, these “leaks” are:

- Copper Losses (I²R Losses): This is the heat generated as electrical current flows through the resistance of the motor’s copper windings in both the stator and rotor. Higher current or higher winding resistance means more energy is lost as heat.

- Iron Losses (Core Losses): These losses occur within the motor’s steel core. They are caused by the rapidly changing magnetic field, creating two types of unwanted effects:

- Hysteresis Loss: Energy lost as the magnetic domains within the core material resist being constantly re-aligned.

- Eddy Current Loss: Small, circulating “whirlpools” of electrical current induced in the core by the magnetic field. These currents produce heat and waste energy. This is precisely why motors are built with thin, insulated motor core laminations—to break up these whirlpools and minimize the loss.

- Friction and Windage Losses: These are purely mechanical losses. Friction comes from the bearings, while windage is the air resistance against the rotating components, including any internal cooling fan.

- Stray Load Losses: A catch-all category for miscellaneous losses that are difficult to measure but occur when the motor is under load.

A motor’s efficiency isn’t just a number on a spec sheet; it’s a critical factor that impacts energy bills, thermal management needs, and the overall reliability of your system.

The Landscape of DC Motors: From Traditional to Modern

The “DC motor” category is where the most confusion—and the most significant technological evolution—has occurred. It’s essential to split this into two distinct groups.

A. Traditional Brushed DC Motors

For decades, when someone mentioned a DC motor, this is what they meant.

How They Work: A traditional DC motor uses a clever mechanical switch called a commutator and a set of carbon brushes to deliver current to the rotating armature. As the armature spins, the commutator segments make and break contact with the brushes, reversing the current direction in the windings to maintain continuous rotation.

Efficiency Characteristics:

These motors were popular for good reason: they offer fantastic starting torque and their speed is incredibly simple to control by just varying the input voltage. However, their design comes with built-in efficiency limitations.

The commutator and brushes are their Achilles’ heel. This mechanical system is a constant source of energy loss through:

- Friction: The physical rubbing of brushes on the commutator.

- Electrical Resistance: Voltage drop across the brushes themselves.

- Arcing: Small sparks that occur as the brushes switch between commutator segments.

Furthermore, these components wear down over time, making brushed DC motors a high-maintenance option for continuous-duty applications. Today, their use is mostly confined to low-cost or intermittent-duty applications like toys, automotive window motors, and starters where long-term efficiency isn’t the primary concern.

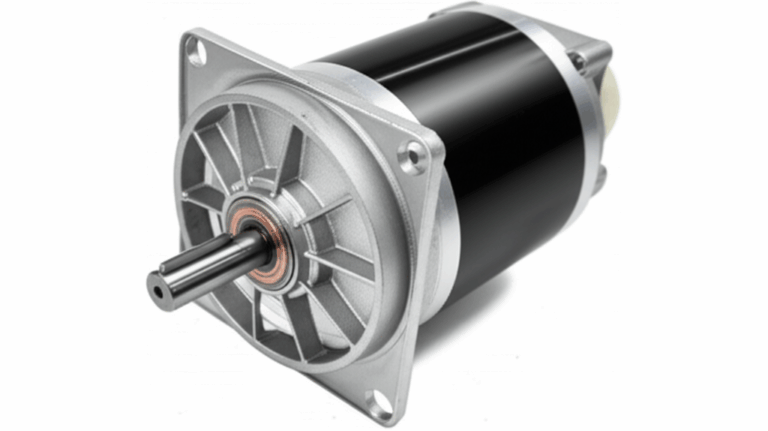

B. Modern Brushless DC (BLDC) and Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSM)

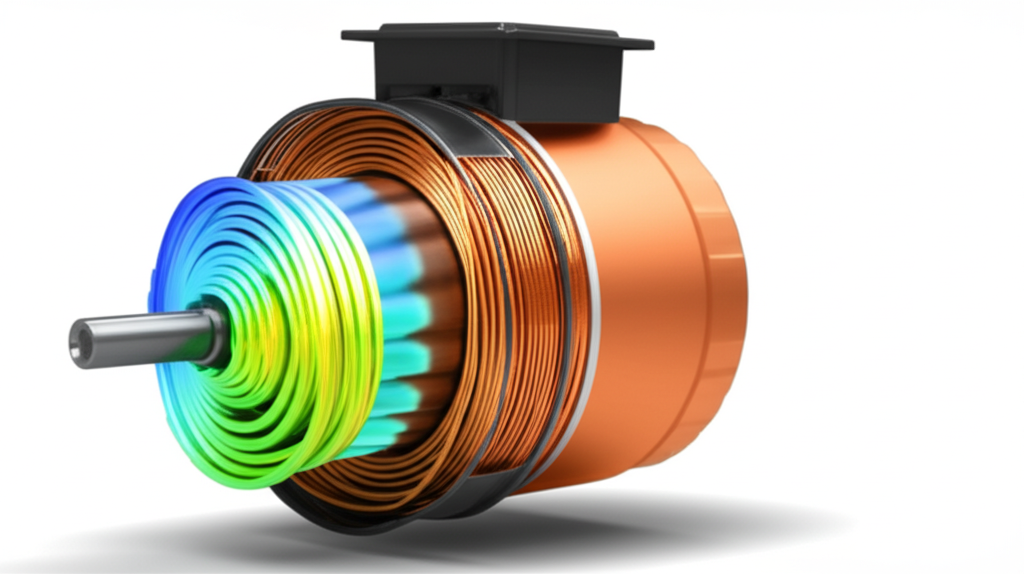

Here’s the most important clarification you’ll read today: Modern “brushless DC” motors are not DC motors in the traditional sense. They are technically three-phase AC synchronous motors that use permanent magnets on the rotor. They are called “DC” because they are powered by a DC source that is converted into AC by an electronic controller.

How They Work: BLDC and PMSM motors brilliantly solve the problems of their brushed predecessors by throwing out the mechanical commutator and brushes entirely. Instead, they use an electronic controller (an inverter) to precisely switch the current in the stationary windings (the stator). This creates a rotating magnetic field that the permanent magnets on the rotor follow. It’s electronic commutation, and it’s a game-changer.

Efficiency Advantages:

By eliminating the brushes, you eliminate a major source of friction, electrical loss, and maintenance. This results in a cascade of benefits:

- Exceptional Efficiency: With no brush losses, BLDC and PMSM motors routinely achieve efficiencies of 85-95% or even higher. Their efficiency also remains high across a much wider range of speeds and loads compared to other motor types.

- High Power Density: They pack more power into a smaller, lighter package.

- Excellent Heat Dissipation: The heat-generating windings are on the stationary outer part of the motor (stator), making it easier to cool.

- Long Lifespan & Low Maintenance: The only wearing parts are the bearings.

These motors have become the standard for high-performance applications. You’ll find them in electric vehicles, high-end HVAC systems (often called ECMs), robotics, drones, and precision industrial machinery. The design of the bldc stator core is critical to maximizing their performance and efficiency.

The Landscape of AC Motors: Induction and Synchronous

AC motors are the undisputed workhorses of industry, primarily because they can be run directly from the grid.

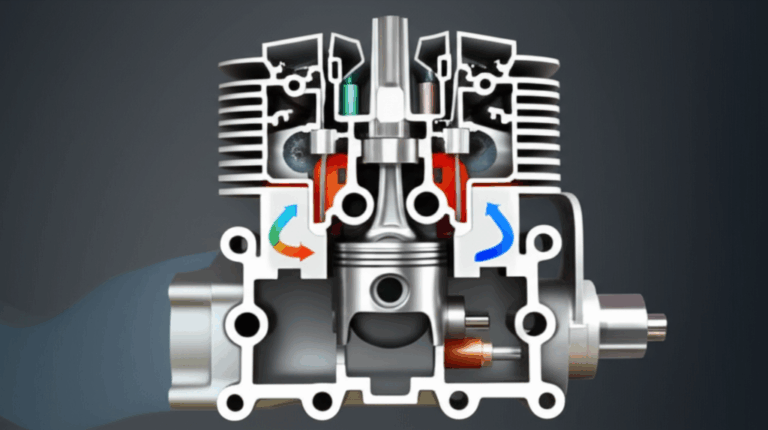

A. AC Induction Motors (AIM)

The squirrel-cage AC induction motor is the most common motor in the world for a reason.

How They Work: An AC induction motor is a marvel of simplicity. AC power is fed to the stator windings, creating a rotating magnetic field. This field induces a current in the rotor bars (which look like a squirrel cage, hence the name). This induced current creates its own magnetic field, which tries to catch up to the stator’s field, causing the rotor to spin. The key is that the rotor always spins slightly slower than the magnetic field—a phenomenon called “slip,” which is necessary to induce current.

Efficiency Characteristics:

- Robust and Reliable: With no brushes to wear out, they are incredibly durable and require minimal maintenance.

- Cost-Effective: Their simple design makes them inexpensive to manufacture.

- High Efficiency Ratings: Modern induction motors, built to standards like NEMA Premium or IEC efficiency classes (IE3, IE4), can be very efficient, often reaching 90-96% at their full rated load.

However, their efficiency can drop significantly when operated at partial loads. This is where the Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) comes in.

The Impact of Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs):

A VFD is an electronic controller that takes standard AC power, converts it to DC, and then inverts it back into a clean, variable AC waveform. This allows for precise control over the motor’s speed. For applications like pumps and fans where the load varies, a VFD can produce massive energy savings (30-50% or more) by slowing the motor down instead of using inefficient mechanical methods like throttling valves or dampers. While the VFD itself has small losses (2-3%), the overall system efficiency is dramatically improved.

B. Synchronous Motors

As the name implies, these motors have a rotor that rotates in perfect sync with the stator’s magnetic field (zero slip). We’ve already discussed the most popular type—the PMSM—in the “modern DC” section. Another important variant is the Synchronous Reluctance Motor (SynRM). SynRMs have a specially shaped steel rotor with no magnets or windings. They rely on the principle of magnetic reluctance to rotate and require a VFD to operate, but they offer very high efficiency (IE4 capable) and are extremely robust, making them a strong, magnet-free alternative to PMSMs in industrial applications.

Direct Comparison: AC vs. DC Motor Efficiency Factors

Now let’s put them head-to-head based on common operating conditions.

| Motor Type | Typical Full Load Efficiency | Key Efficiency Drivers / Limitations | Best Suited For (Common Applications) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Brushed DC | 70-85% | Limitations: Commutator/brush friction, electrical losses, brush wear. | Low-cost, intermittent duty (small appliances, toys). |

| Standard AC Induction | 80-92% | Limitations: Rotor copper losses (slip), inefficient at partial loads. | Fixed-speed industrial pumps, fans, conveyors. |

| NEMA Premium / IE3/IE4 AIM | 90-96%+ | Drivers: Optimized design, high-quality materials, reduced losses. | Continuous, energy-intensive industrial applications. |

| AIM with VFD (System) | 85-95% | Drivers: Optimizes motor speed for load, huge system-level savings. | Variable flow/pressure applications (HVAC, pumps). |

| Brushless DC (BLDC) | 85-95%+ | Drivers: No brushes/commutator losses, permanent magnets. | Drones, robotics, HVAC (ECM fans), consumer electronics. |

| PMSM (AC Synchronous) | 90-97%+ | Drivers: No rotor current losses, high power density. | Electric Vehicles, industrial servo drives, wind turbines. |

| SynRM (AC Synchronous) | 92-96%+ | Drivers: No magnets, no rotor current losses, requires VFD. | Industrial fans, pumps where high efficiency and ruggedness are key. |

A. At Fixed Speed and Full Load

In a straightforward, fixed-speed industrial application, a NEMA Premium AC induction motor is a highly efficient and cost-effective choice. It can match or even slightly exceed the efficiency of a traditional brushed DC motor. However, modern PMSM or SynRM motors will generally be the most efficient options of all due to the elimination of rotor current losses.

B. At Variable Speed and Partial Load

This is where the real separation happens.

- Brushed DC: Efficiency drops, and brush wear can accelerate.

- AC Induction with VFD: Offers excellent efficiency. The ability to match speed to demand is a huge energy saver.

- BLDC/PMSM: This is their sweet spot. These motors maintain incredibly high efficiency across a vast range of speeds and loads, making them the undisputed champions for dynamic, variable-speed applications like electric vehicles and robotics. The quality of the rotor core lamination plays a vital role in managing losses at the high frequencies often seen in these variable-speed drives.

C. Power Conversion and System Efficiency

It’s crucial to look at the whole system. A BLDC motor might be 95% efficient, but it requires a controller that might be 97% efficient, for a total system efficiency of about 92%. Similarly, an AC motor with a VFD has the motor’s efficiency and the VFD’s efficiency to consider. The key takeaway is that the minor losses from modern power electronics are a small price to pay for the massive gains in control and operational efficiency they unlock.

Modern Trends and The Verdict on Efficiency

So, let’s revisit our original question. If we rephrase it for today’s technology, here is the definitive answer.

1. Traditional brushed DC motors are the least efficient modern motor technology for most applications. Their reliance on a mechanical commutator creates inherent losses and maintenance issues that have been solved by other designs.

2. Modern, electronically commutated motors (BLDC and PMSM) are typically the most efficient electric motors available today. Their brushless design and use of permanent magnets minimize internal losses, giving them superior performance, especially in variable-speed, high-power-density applications. They are the clear winners in the efficiency race.

3. High-efficiency AC induction motors (NEMA Premium/IE4) combined with VFDs offer a robust, reliable, and highly efficient solution for a vast range of industrial applications. While a PMSM might be slightly more efficient on paper, a well-implemented VFD-driven induction motor system provides outstanding performance and energy savings.

The trend is clear: the industry is moving away from mechanical commutation and toward electronically controlled systems. Whether it’s a VFD intelligently controlling an AC induction motor or an inverter driving a PMSM in an EV, the future of motor efficiency lies in precise electronic control.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Are BLDC motors truly “DC” motors?

No, not in the way they operate. They are three-phase AC synchronous motors. They get the “DC” name because the system is often powered by a DC source (like a battery) and the electronic controller that creates the AC waveforms is integrated with the motor.

Why are AC induction motors still so widely used?

They are incredibly reliable, low-cost, and require almost no maintenance. For fixed-speed applications where they can run at their optimal load, they provide a fantastic balance of performance, cost, and efficiency. The global infrastructure is also built around AC power, making them easy to deploy.

Does a VFD always make an AC motor more efficient?

No. A VFD introduces its own small energy loss (2-3%). If you have an application that runs at a constant, full speed 100% of the time, connecting the motor directly to the line is slightly more efficient. However, in the vast majority of real-world applications where speed or load varies (like pumps, fans, and conveyors), a VFD will result in significant overall system energy savings by eliminating much larger mechanical inefficiencies.

Which motor type is preferred for electric vehicles and why?

Most modern electric vehicles primarily use Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs). They are chosen for their unmatched combination of high efficiency across a wide speed/torque range (which translates to longer battery range), high power density (more power in a smaller space), and instant torque delivery for excellent performance.

What is the difference between IE3 and IE4 efficiency classes?

These are standards set by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). IE3 is “Premium Efficiency” and IE4 is “Super Premium Efficiency.” Each class represents a significant reduction in energy losses compared to the previous one. For example, moving from IE3 to IE4 can reduce motor losses by about 15-20%, leading to substantial long-term energy savings in continuous-duty applications.