Does Carbon Steel Conduct Electricity? A Comprehensive Guide to its Electrical Properties

As someone who has spent years working with different materials in both structural and electrical projects, I’ve seen this question pop up time and time again. “Does carbon steel conduct electricity?” It seems simple, but the answer has some important nuances that can make or break a project, or even create a serious safety hazard.

Let’s clear this up right away.

Yes, carbon steel absolutely conducts electricity. But that’s just the beginning of the story. The real questions are: How well does it conduct? What makes it conductive? And when should you (or shouldn’t you) rely on it for an electrical application?

Over the years, I’ve learned these lessons firsthand, sometimes the hard way. I want to walk you through everything I’ve discovered about the electrical properties of carbon steel, from the basic science to the practical, real-world implications I see every day.

Table of Contents

- What Makes a Material Conductive Anyway? The Science Behind It

- How Well Does Carbon Steel Conduct Electricity? (Comparisons & Benchmarks)

- Key Factors Influencing Carbon Steel’s Electrical Conductivity

- Carbon Content: The Defining Element

- Alloying Elements: The Other Ingredients

- Temperature: The Heat Factor

- Impurities and Microstructure

- Practical Implications and Real-World Applications

- Grounding Systems: The Unsung Hero

- Electrical Enclosures & Conduits: Protective Pathways

- Structural Components: The Hidden Conductor

- Welding Processes: A Necessary Partnership

- Electrical Safety: The Non-Negotiable

- Carbon Steel vs. Other Steels: A Conductivity Snapshot

- Conclusion: Making Informed Decisions About Carbon Steel

What Makes a Material Conductive Anyway? The Science Behind It

Before we dive deep into steel, let’s take a quick step back. Understanding why something conducts electricity makes everything else click into place. I remember in my early days, I just accepted “metals conduct,” but knowing the ‘why’ changed how I approached material selection.

Think of it like this: electrical current is just the flow of electrons. For electrons to flow easily, a material needs two things:

Metals, including carbon steel, are perfect for this because of something called metallic bonding. In a piece of steel, the iron atoms are arranged in a neat, crystalline grid called a lattice structure. But the outermost electrons of these atoms aren’t stuck to their home atom. Instead, they form a “sea” of delocalized or free electrons that can wander throughout the entire piece of metal.

When you apply a voltage (an electrical potential) across a piece of steel, these free electrons are immediately pushed from the negative end to the positive end. Voilà! You have an electrical current. Materials that don’t have this sea of free electrons, like plastic or rubber, are insulators because there’s nothing available to move and carry a charge.

Now, this brings up two key terms you’ll see a lot:

- Conductivity: This is a measure of how easily current can flow through a material. Higher conductivity means less resistance to flow. The unit for this is often Siemens per meter (S/m).

- Resistivity: This is the exact opposite. It measures how much a material resists the flow of current. It’s an intrinsic property of the material itself. You’ll usually see it measured in Ohm-meters (Ω·m) or, for practical purposes, microhm-centimeters (µΩ·cm).

So, in short: High Conductivity = Low Resistivity. For a great conductor, you want the resistivity to be as low as possible.

How Well Does Carbon Steel Conduct Electricity? (Comparisons & Benchmarks)

So we’ve established that carbon steel is a conductor. But is it a good one? This is where I see a lot of confusion. People hear “metal” and think it’s as good as the copper in their electrical wiring. That’s a dangerous assumption.

The truth is, carbon steel is a decent conductor, but it’s not in the same league as premium conductors like copper, silver, or aluminum.

Let’s put some real numbers to this. The industry standard for comparing conductors is the International Annealed Copper Standard (IACS). Pure annealed copper is set as the benchmark at 100% IACS. Everything else is measured against it.

Here’s a look at where common materials stand, based on data I’ve consistently used for material selection:

| Material | Electrical Resistivity (µΩ·cm) at 20°C | Electrical Conductivity (% IACS) at 20°C |

|---|---|---|

| Silver | 1.59 | 106% |

| Pure Copper | 1.68 | 100% (The Benchmark) |

| Aluminum | 2.82 | 61% |

| Low Carbon Steel | 15 – 20 | 8 – 11% |

| High Carbon Steel | 25 – 30+ | 5 – 7% |

| Stainless Steel (304) | 72 | 2.4% |

| Nichrome | 100 – 150 | ~1% |

| Glass/Rubber | Extremely High | Effectively 0% (Insulator) |

Right away, you can see the story these numbers tell. Low carbon steel, one of the more conductive types, has a conductivity that’s only about 8-11% that of copper. This means for the same size and shape, it has roughly 10 times more electrical resistance.

This single fact is why you don’t see electrical wiring made of steel. The energy loss due to resistance would be enormous, generating a lot of heat and wasting power. However, for many other applications, that level of conductivity is not only acceptable but perfectly suitable. It’s all about choosing the right tool for the job.

Key Factors Influencing Carbon Steel’s Electrical Conductivity

One of the most fascinating things I learned about steel is that “carbon steel” isn’t one single material. It’s a family of alloys, and small changes in its recipe can significantly alter its properties, including electrical conductivity.

Imagine our sea of electrons again. Anything that disrupts the nice, orderly lattice structure of the iron atoms acts like a rock in a river, making it harder for the electrons to flow smoothly. This increases resistivity.

Here are the main culprits I always have to consider.

Carbon Content: The Defining Element

It’s right there in the name! The amount of carbon is the primary factor that defines the type of carbon steel and its mechanical properties like strength and hardness. It also has a direct impact on conductivity.

- Low Carbon Steel (Mild Steel): Contains up to about 0.3% carbon. Because it’s mostly pure iron, its lattice is relatively uniform. This gives it the lowest resistivity (and highest conductivity) in the carbon steel family.

- Medium Carbon Steel: Has about 0.3% to 0.6% carbon. The extra carbon atoms distort the iron lattice, scattering the electrons more. This increases resistivity.

- High Carbon Steel: Contains more than 0.6% carbon. It’s very hard and strong but has the highest resistivity of the group because the lattice is even more disrupted.

The takeaway is simple: as carbon content goes up, electrical conductivity goes down. It’s not a massive drop, but it’s a measurable and important effect.

Alloying Elements: The Other Ingredients

Carbon isn’t the only thing mixed with iron. Steels often contain other elements like manganese, silicon, phosphorus, and sulfur, either as impurities or intentional additions. Just like carbon, these foreign atoms mess with the lattice structure and increase resistivity. This is a huge reason why stainless steel, which is loaded with chromium and nickel, is a much poorer conductor than plain carbon steel.

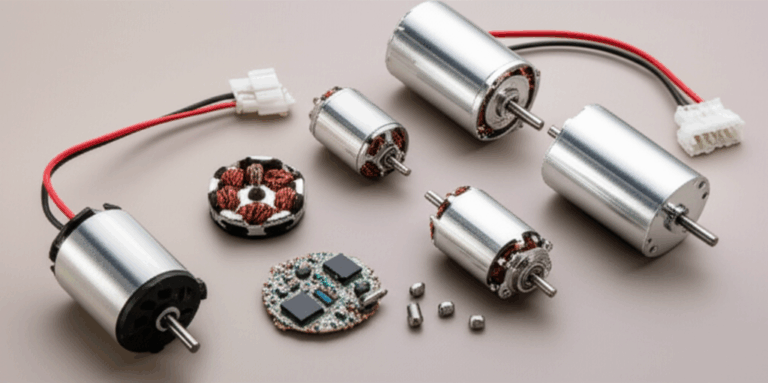

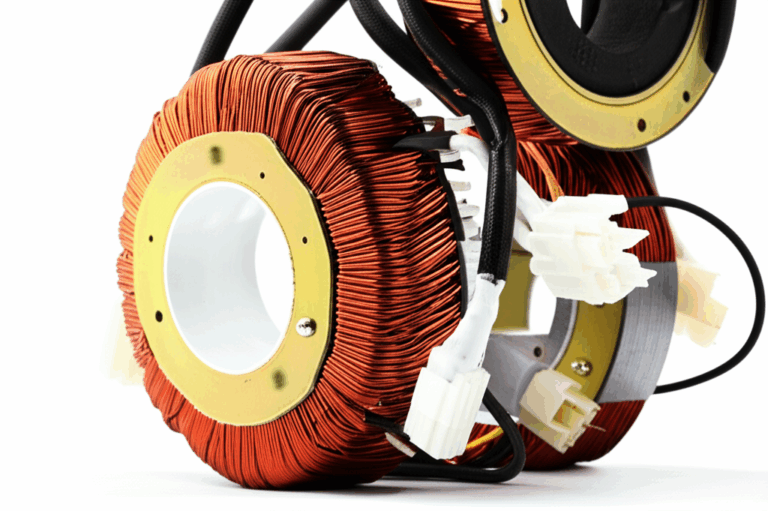

In specialized applications, we even add elements specifically to alter these properties. For example, in the world of motors and transformers, silicon steel laminations are used because the addition of silicon dramatically increases resistivity, which helps reduce energy losses from unwanted eddy currents.

Temperature: The Heat Factor

This is a big one that catches people by surprise. For most metals, including carbon steel, conductivity decreases as temperature rises.

Why? When you heat a metal, its atoms vibrate more intensely. Think of it as the “rocks” in our river analogy starting to shake and move around. This increased vibration makes it far more likely that a flowing electron will collide with an atom, scattering it and impeding its progress. This effect is quite significant; the resistivity of steel can increase by about 0.3-0.5% for every degree Celsius it heats up.

I’ve had to account for this in designs where components might run hot. A steel part that functions perfectly as a ground at room temperature might have too much resistance to do its job safely when it’s next to a hot engine or furnace.

Impurities and Microstructure

Even tiny amounts of impurities can affect conductivity. Furthermore, how the steel is processed—things like heat treatment (annealing, quenching, tempering)—changes its internal crystal structure, or microstructure. While this effect is generally less pronounced than that of alloys or temperature, it can still cause minor variations in electrical properties.

Practical Implications and Real-World Applications

This is where the rubber meets the road. Knowing the theory is great, but understanding how carbon steel’s conductivity plays out in the real world is what truly matters. I’ve used, installed, and worked around carbon steel in countless electrical contexts. Here are the most common scenarios.

Grounding Systems: The Unsung Hero

One of the most common places you’ll find carbon steel in an electrical system is in grounding rods. You might think, “Why not use a copper rod if it’s a better conductor?”

The answer is a classic engineering trade-off: cost vs. performance. While a copper rod would be a slightly better electrical ground, a galvanized carbon steel rod is more than “good enough” for the job. Its job is to provide a safe path for fault currents (like from a lightning strike or short circuit) to dissipate into the earth. It doesn’t need to be hyper-efficient like a power line.

What steel brings to the table is immense strength and a much lower cost. It can be hammered into hard ground without bending or breaking. The zinc galvanizing layer provides corrosion resistance, ensuring it lasts for years. In this application, steel’s blend of adequate conductivity, mechanical toughness, and affordability makes it the perfect choice.

Electrical Enclosures & Conduits: Protective Pathways

Take a look at any industrial facility or commercial building, and you’ll see metal boxes (enclosures) and pipes (conduits) everywhere. Most of these are made from carbon steel.

Their primary job is to physically protect the electrical wiring inside. However, their conductivity plays a crucial secondary role in safety. If a live wire inside the conduit accidentally touches the metal wall, the conduit itself becomes part of the circuit. Because it’s conductive and properly bonded to the grounding system, it provides a low-resistance path for the fault current to flow. This trips the circuit breaker immediately, shutting off the power and preventing the conduit from becoming an electrocution hazard.

If conduits were made of an insulator, that frayed wire would just sit there, energizing the entire metal shell and waiting for someone to touch it. Steel’s conductivity is a built-in safety feature.

Structural Components: The Hidden Conductor

This is an area where I’ve seen major problems arise from a lack of awareness. Steel I-beams, support columns, and frames are everywhere. And because they are conductive, they can become an unintentional part of an electrical circuit.

I once investigated an issue at a processing plant where sensitive electronic equipment was failing randomly. It turned out that a large motor was improperly grounded, and stray currents were traveling through the building’s steel frame, creating electrical “noise” that interfered with the electronics.

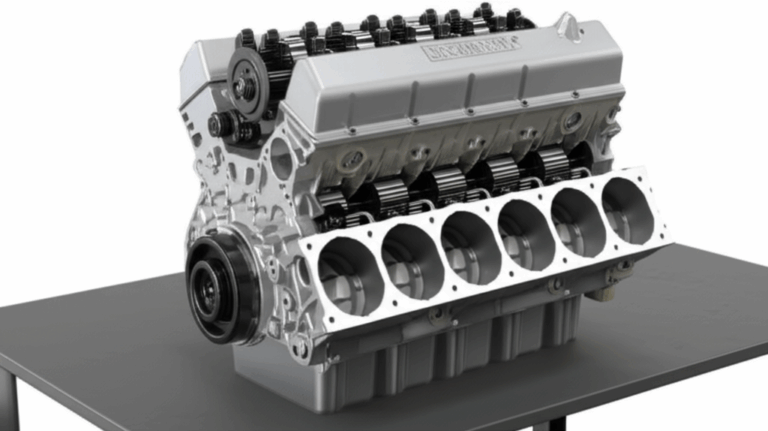

This highlights a critical point: in any environment with electrical systems, you must treat all structural steel as a potential conductor. This is why bonding and grounding standards are so strict in industrial and commercial construction. You have to ensure that all metallic components are tied to a common ground to prevent dangerous voltage differences from building up. Understanding how the stator and rotor interact in motors, and how their stray currents can escape, is vital.

Welding Processes: A Necessary Partnership

Arc welding is fundamentally an electrical process. An electric arc is created between an electrode and the steel workpiece, generating intense heat that melts and fuses the metal.

For this to work, the carbon steel itself must be part of the electrical circuit. You clamp a ground cable to the steel part you’re welding, and the current flows from the welder, through the electrode, across the arc, and through the steel back to the machine. Without steel’s ability to conduct electricity, arc welding simply wouldn’t be possible. The resistance within the steel even contributes to the overall heat generation needed for a successful weld.

Electrical Safety: The Non-Negotiable

The biggest takeaway from all this is safety. Because carbon steel conducts electricity, you must always treat it with respect when it’s anywhere near a live circuit.

- Assume it’s live: If a steel tool, pipe, or structure is touching or could potentially touch an energized wire, assume the entire piece of steel is live.

- Insulation is key: This is why tools used by electricians have thick rubber or plastic handles. The steel shank is a conductor, but the handle provides insulation.

- Grounding, grounding, grounding: I can’t say it enough. Proper grounding is what makes systems with steel components safe. It ensures that if something goes wrong, the electricity has a safe place to go instead of through a person.

Carbon Steel vs. Other Steels: A Conductivity Snapshot

It’s helpful to see how carbon steel stacks up against its relatives in the steel family.

- Carbon Steel: As we’ve seen, it’s a decent conductor. Its conductivity is primarily determined by its carbon content—lower carbon means higher conductivity.

- Stainless Steel: This is a much poorer conductor. The high amounts of chromium (for rust resistance) and often nickel severely disrupt the iron lattice, increasing resistivity dramatically. A typical 304 stainless steel might have only 2-3% the conductivity of copper, making it about 4-5 times less conductive than a low-carbon steel. I’ve seen it used where you need corrosion resistance but less electrical conductivity.

- Cast Iron: Its properties can vary a lot, but it’s generally less conductive than carbon steel. The presence of large graphite flakes or nodules within the iron matrix creates major disruptions for electron flow.

This is why you don’t use stainless steel for grounding rods or cast iron for electrical conduits. Carbon steel hits the sweet spot of properties for many of these applications. Specialized materials like electrical steel laminations are engineered for even more specific roles, like in the cores of motors and transformers where managing both electrical and magnetic fields is critical. For instance, the design of a transformer lamination core relies on steel with high resistivity to minimize energy loss.

Conclusion: Making Informed Decisions About Carbon Steel

So, let’s circle back to our original question: Does carbon steel conduct electricity?

The answer is a definitive yes. It’s a conductor because its metallic structure is full of free-flowing electrons ready to carry a current.

But the most important lesson I’ve learned is that the simple “yes” isn’t enough. The key is understanding its place in the world of conductors. It’s not a high-performance material like copper, but it’s not an insulator either. It occupies a middle ground that, when combined with its incredible strength, workability, and low cost, makes it one of the most versatile and essential materials in both the structural and electrical worlds.

Whether you’re designing a grounding system, installing electrical conduit, or simply working safely around steel structures, knowing that steel is a conductor—and understanding the factors that influence how well it conducts—is fundamental. It allows you to make smart, safe, and effective decisions, turning a simple material property into a powerful engineering tool.