Does Galvanized Steel Conduct Electricity? A Comprehensive Guide to its Electrical Properties

If you’re an engineer or designer, you know that material selection is a game of trade-offs. You’re constantly weighing strength against cost, and corrosion resistance against manufacturability. When it comes to applications involving electricity, another critical property enters the mix: conductivity. This brings us to a question that frequently comes up in workshops, design meetings, and on job sites: Does galvanized steel conduct electricity?

The short answer is: Yes, absolutely.

But as with any serious engineering question, the short answer is rarely the whole story. Galvanized steel’s role in electrical systems is far more nuanced. It isn’t just about whether a current can pass through it but about how well it does, what factors affect its performance over time, and where its unique combination of properties makes it the ideal choice over other metals. Understanding these details is crucial for ensuring the safety, longevity, and reliability of your electrical designs.

What We’ll Cover

This guide will walk you through everything you need to know about the electrical properties of galvanized steel. We’ll explore:

- The fundamental science behind its conductivity.

- Key factors that can alter its electrical performance.

- Its most common and critical roles in electrical applications.

- How it stacks up against other conductive materials like copper and plain steel.

- Potential downsides and critical engineering considerations.

The Science Behind Conductivity: A Look Under the Hood

To really grasp why galvanized steel is a conductor, we need to quickly look at its components and the basic physics of electrical flow in metals.

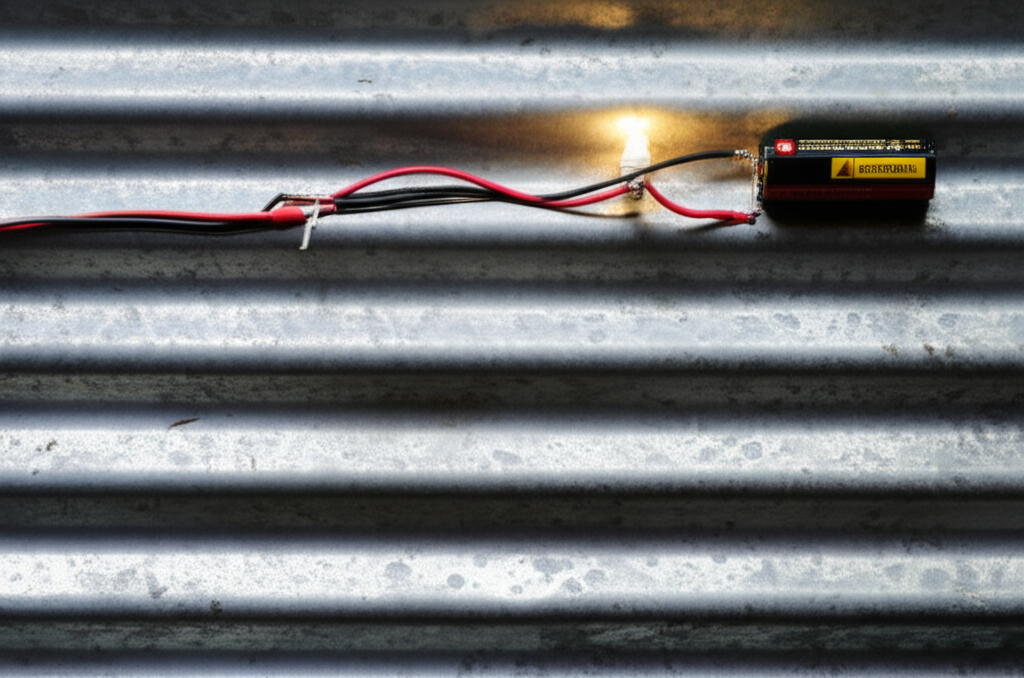

How Metals Conduct Electricity in the First Place

Think of the atomic structure of a metal as a tightly packed lattice of positively charged ions. Surrounding this lattice is a shared “sea” of free-floating electrons. These electrons aren’t tied to any single atom; they’re free to roam throughout the material.

When you apply a voltage across the metal, it creates an electric field. This field acts like a current in a river, pushing the free electrons to flow in a coordinated direction from a negative to a positive potential. This directed flow of electrons is what we call electrical current. The more free electrons a material has and the more easily they can move, the better it conducts electricity.

The Conductivity of Steel and Zinc

Galvanized steel isn’t a single material but a composite. It’s a steel base with a protective coating of zinc. So, to understand its conductivity, we have to look at both parts.

Because both the steel core and the zinc coating are conductors, the entire composite material—galvanized steel—readily conducts electricity. The current can flow through the zinc layer, the steel core, and the intermetallic layers formed between them during the galvanizing process.

Factors Influencing Galvanized Steel’s Electrical Properties

While galvanized steel is fundamentally conductive, its real-world performance isn’t static. Several factors can influence its electrical resistance, and these are critical for any engineer to consider.

Surface Condition: The Oxide Problem

This is arguably the most important factor. When zinc is exposed to the atmosphere, it reacts with oxygen and carbon dioxide to form a thin, stable, and non-porous layer of zinc oxide and zinc carbonate. This passivation layer is fantastic for corrosion protection—it’s the very reason we galvanize steel.

However, zinc oxide is a semiconductor with very high resistivity, meaning it’s a poor conductor of electricity compared to pure zinc.

What does this mean for you? For applications where current flows through the bulk of the material, like a conduit acting as a ground path, this thin surface layer has a negligible effect. The electricity simply flows through the vast, highly conductive metal underneath.

But for applications requiring a reliable connection at the surface—like a grounding clamp attached to a galvanized pipe—this oxide layer can increase contact resistance. Over time, this can lead to a less reliable electrical bond if the connection isn’t properly made. That’s why electrical codes often require scraping or using specialized listed clamps that can bite through this oxide layer to ensure a solid metal-to-metal connection.

Zinc Coating Thickness

The thickness of the zinc coating, determined by whether it’s hot-dip galvanized or electro-galvanized, can have a minor impact. A thicker zinc layer, being more conductive than the steel, might slightly decrease the overall surface resistance of the component. However, since the bulk of the material is steel, its influence on the overall conductivity is usually minimal and not a primary design consideration for most grounding and conduit applications.

Temperature

Like most metals, galvanized steel’s electrical resistance increases as its temperature rises. This happens because the atoms in the metal lattice vibrate more intensely at higher temperatures, getting in the way of the flowing electrons and making their journey more difficult. For the vast majority of electrical applications involving galvanized steel (like grounding and conduit), this effect is well within acceptable limits and doesn’t pose a practical problem.

Galvanized Steel in Electrical Applications: Where It Shines

So, if it’s not as conductive as copper, why is galvanized steel so widespread in electrical systems? Because it offers an unbeatable combination of strength, corrosion resistance, conductivity, and cost-effectiveness.

Grounding and Earthing

Grounding (or earthing) is a critical safety measure that provides a safe path for fault currents to flow to the earth. A good grounding system protects people from electric shock and equipment from damage.

Galvanized steel is a star player here for several reasons:

- Corrosion Resistance: Grounding electrodes, like grounding rods and pipes, are often buried in soil, which can be moist and corrosive. Plain steel would rust away quickly, and that rust (iron oxide) is a terrible conductor. The zinc coating on galvanized steel acts as a sacrificial anode, protecting the steel core for decades and ensuring the grounding path remains intact and conductive. The quality of various motor core laminations is crucial, and similarly, the integrity of grounding materials is paramount for safety.

- Conductivity: It is more than conductive enough to safely carry large fault currents to the ground.

- Strength and Cost: It’s strong enough to be driven into hard soil and is significantly cheaper than using solid copper rods, especially for large projects.

Proper electrical bonding is crucial when using galvanized structural steel or pipes as part of a grounding system to ensure electrical continuity across all connections.

Conduit, Raceways, and Enclosures

Walk onto any commercial or industrial construction site and you’ll see miles of galvanized steel conduit, such as Electrical Metallic Tubing (EMT) or Rigid Metallic Conduit (RMC).

Here, galvanized steel serves three vital functions simultaneously:

Structural Applications and Lightning Protection

Many large structures, from communications towers to substation support structures, are built using galvanized steel. Its inherent conductivity allows these structures to be integrated directly into lightning protection systems. When properly grounded, a galvanized steel frame can safely conduct the massive current from a lightning strike to the earth, protecting the structure and the equipment within it.

Comparing Galvanized Steel to Other Conductors

To make the right design choice, it helps to see how galvanized steel stacks up against the alternatives.

| Material | Primary Composition | Electrical Conductivity (S/m) at 20°C (approx.) | Electrical Resistivity (Ω·m) at 20°C (approx.) | Key Electrical Role/Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper (Pure) | Cu | 5.96 x 10^7 | 1.68 x 10^-8 | Excellent conductor, standard for wiring, high current carrying. |

| Aluminum (Pure) | Al | 3.77 x 10^7 | 2.65 x 10^-8 | Very good conductor, lighter than copper, used for overhead lines. |

| Mild Steel | Fe, C | 5.9 x 10^6 – 1.0 x 10^7 | 1.0 x 10^-7 – 1.7 x 10^-7 | Good conductor, but prone to rust, which is an insulator. |

| Zinc (Pure) | Zn | 1.6 x 10^7 – 1.7 x 10^7 | 5.9 x 10^-8 – 6.2 x 10^-8 | Good conductor, primary component of galvanization. |

| Galvanized Steel | Steel + Zinc | ~5.9 x 10^6 – 1.7 x 10^7 | ~5.9 x 10^-8 – 1.7 x 10^-7 | Conductive, with excellent corrosion resistance. Used for conduits and grounding. |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) | ZnO | 1 x 10^-13 – 1 x 10^-4 | 1 x 10^4 – 1 x 10^13 | Semiconductor/insulator. Increases surface contact resistance. |

| Iron Rust (Fe2O3) | Iron Oxides | 1 x 10^-16 – 1 x 10^-3 | 1 x 10^3 – 1 x 10^16 | Poor conductor/insulator. Destroys electrical continuity. |

Galvanized Steel vs. Copper

There’s no contest here in pure conductivity; copper is about six times more conductive than steel. This is why we don’t make wires out of steel. The energy loss (as heat) would be far too high.

- Choose Copper for wiring and dedicated conductors where electrical efficiency is the top priority.

- Choose Galvanized Steel where you need a combination of conductivity, structural strength, and corrosion resistance at a lower cost, as in conduit and grounding electrodes. This is why we use high-quality electrical steel laminations for motor and transformer cores, where magnetic properties are key, but copper for the windings.

Galvanized Steel vs. Plain Steel

Their bulk electrical conductivity is nearly identical. The defining difference is performance over time. Plain steel will rust when exposed to moisture. This rust layer is highly resistive and will eventually compromise or completely destroy any intended electrical path. The zinc coating on galvanized steel prevents this, ensuring a reliable conductive path for many years. It is this marriage of conductivity and longevity that sets it apart. The complex interplay between the stator and rotor in a motor relies on materials maintaining their properties over time, just as a grounding system relies on the lasting conductivity of galvanized steel.

Potential Downsides and Engineering Considerations

While incredibly useful, galvanized steel isn’t without its challenges. A smart designer knows the limitations of their materials.

Galvanic Corrosion with Dissimilar Metals

This is a big one. The very thing that makes galvanized steel great at protecting itself—its willingness to sacrifice itself—can be a problem if it’s connected to the wrong metal.

The galvanic series tells us how different metals will behave when in electrical contact in the presence of an electrolyte (like water). Zinc is a very “active” metal, while copper is much more “noble.” If you connect a galvanized steel pipe directly to a copper pipe or use a copper grounding clamp on a galvanized rod in a wet environment, you create a battery. The more active zinc will corrode rapidly to protect the more noble copper, destroying the galvanized coating and compromising the connection.

To prevent this, you must use the right connectors. Dielectric unions or bronze/stainless steel clamps are often used to separate the dissimilar metals and prevent this corrosive reaction.

Welding Safety

When galvanized steel is welded, the zinc coating vaporizes, creating zinc oxide fumes. Inhaling these fumes can cause a flu-like illness called “metal fume fever.” While not directly an electrical issue, it’s a critical safety hazard for anyone working with galvanized steel in electrical installations. Proper ventilation and personal protective equipment (PPE) are absolutely essential.

Your Engineering Takeaway: A Conductive Conclusion

Let’s circle back to our original question. Does galvanized steel conduct electricity? Yes. But the real takeaway is that its value lies in its unique balance of properties.

Here’s a summary of the key points to remember:

- It is a reliable conductor. Both its steel core and zinc coating are conductive, making it suitable for applications like grounding paths and conduit.

- Its primary advantage is durability. The zinc coating provides exceptional corrosion resistance, ensuring the electrical path remains intact for decades in harsh environments where plain steel would fail.

- Surface condition matters. A zinc oxide layer can form on the surface, increasing contact resistance. Always use appropriate connectors designed to ensure a solid, long-lasting electrical bond.

- Beware of galvanic corrosion. Avoid direct contact between galvanized steel and more noble metals like copper in moist environments to prevent accelerated corrosion.

Galvanized steel is a workhorse material in the electrical world. It’s not the most conductive material available, but for countless applications—from the grounding rod buried in your backyard to the conduit running through a skyscraper—its blend of strength, cost-effectiveness, and corrosion-resistant conductivity makes it an indispensable and intelligent engineering choice. When designing systems that rely on these properties, like a transformer lamination core that needs to manage magnetic fields efficiently, understanding every aspect of your material is key to success.