Does Mild Steel Conduct Electricity? A Comprehensive Guide

If you’re an engineer, designer, or fabricator, you know that material selection is everything. Every choice comes with a cascade of consequences for performance, cost, and safety. You’ve likely found yourself asking a seemingly simple question that has complex implications: does mild steel conduct electricity? It’s a critical point of curiosity, whether you’re designing an electrical enclosure, specifying a structural frame for a factory, or just ensuring a project is safe. You’re in the right place for a straight answer and a deep dive into the engineering principles behind it.

In This Article

- Yes, Mild Steel Conducts Electricity.

- Why Mild Steel Conducts Electricity: The Science Behind It

- How Well Does Mild Steel Conduct Electricity? (Resistivity & Conductivity)

- Factors Affecting Mild Steel’s Electrical Conductivity

- Practical Applications of Mild Steel’s Electrical Conductivity

- Electrical Safety Considerations with Mild Steel

- Key Takeaways: Mild Steel is a Conductor, But with Caveats.

Yes, Mild Steel Conducts Electricity.

Let’s get right to the point: Yes, mild steel absolutely conducts electricity.

Like all metals, it allows electrical current to flow through it. However, and this is the crucial part for any practical application, it’s not a particularly efficient conductor. Think of it less like a superhighway for electricity and more like a bumpy country road. The traffic gets through but there’s a lot more resistance along the way compared to the smooth pavement of materials like copper or aluminum. This distinction is what makes mild steel perfect for some jobs and a downright hazard in others. Understanding this balance between conductivity and resistance is key to using it effectively and safely.

Why Mild Steel Conducts Electricity: The Science Behind It

To really grasp mild steel’s electrical behavior, we need to look at what’s happening on an atomic level. It isn’t magic; it’s physics. The ability of any material to conduct electricity comes down to its atomic structure and the behavior of its electrons.

Metallic Bonding and Free Electrons

Metals are unique because of how their atoms bond together. Instead of holding their outermost electrons tightly, metal atoms share them in a communal “sea” of electrons that are free to wander throughout the entire structure. This is called metallic bonding.

Imagine a neighborhood where every family lets their kids play freely anywhere on the block. These kids can move from one end of the street to the other without being tied to a single house. These are your free electrons, also known as delocalized electrons. When you apply a voltage across a piece of mild steel, you’re essentially creating an electrical “slope.” This electrical potential difference nudges the free electrons to flow in a coordinated direction, from the negative end to the positive end. This flow of electrons is what we call electrical current. It’s this fundamental conduction mechanism in metals that makes mild steel a conductor.

Composition Matters

Mild steel isn’t pure iron; it’s an iron alloy. Its primary components are iron and a very small amount of carbon (typically less than 0.25%).

- Iron (Fe): As a metal, iron forms the metallic lattice and provides the sea of free electrons needed for conduction. Pure iron is a reasonably good conductor.

- Carbon (C): The carbon atoms, along with other trace impurities and alloying elements, don’t fit perfectly into the iron’s crystalline structure. They act like little obstacles or speed bumps in the path of the flowing electrons. The electrons collide with these imperfections, which scatters them and makes their journey more difficult. This scattering is the source of electrical resistance.

The “mild” in mild steel refers to its low carbon content. This makes it ductile and easy to work with but also means it has fewer “obstacles” than high-carbon steel. Consequently, low-carbon steel (mild steel) generally has a higher electrical conductivity than high-carbon steel, where more carbon atoms get in the way of electron flow.

How Well Does Mild Steel Conduct Electricity? (Resistivity & Conductivity)

Knowing that mild steel conducts electricity is one thing. Knowing how well it conducts is what empowers you to make smart design decisions. We measure this using two inverse properties: resistivity and conductivity.

Understanding Electrical Resistivity

Electrical resistivity is a material’s fundamental property that measures how strongly it opposes the flow of electric current. Think of it as electrical friction. A material with high resistivity is a poor conductor (an insulator), while one with low resistivity is a good conductor. We measure it in Ohm-meters (Ω·m).

For mild steel, the typical electrical resistivity falls in the range of 125 to 200 nano-ohm-meters (nΩ·m). This number might seem abstract, so context is everything.

Electrical Conductivity Values

Electrical conductivity is simply the inverse of resistivity. It measures how easily current can flow through a material. It’s the “go” to resistivity’s “stop.” The standard unit is Siemens per meter (S/m), often expressed as MegaSiemens per meter (MS/m) for metals.

Mild steel’s conductivity is typically around 5 to 8 MS/m. Again, let’s put that in perspective by comparing it to the materials you’re most likely considering for electrical applications.

Comparison with Other Common Metals

This is where the rubber meets the road. Mild steel’s utility as a conductor is defined by how it stacks up against the competition. A common way to standardize this is with the IACS (International Annealed Copper Standard), which sets pure annealed copper at 100%.

| Property | Mild Steel (Typical) | Copper (Annealed) | Aluminum (Pure) | Stainless Steel (304) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical Conductivity | 5 – 8 MS/m | 59.6 MS/m | 37.8 MS/m | 1.4 – 1.5 MS/m |

| % IACS | 8 – 14% | 100% | 63% | ~2.5% |

| Electrical Resistivity | 125 – 200 nΩ·m | 16.78 nΩ·m | 26.55 nΩ·m | ~720 nΩ·m |

| Primary Use as Conductor | Structural, Grounding | Excellent Primary Conductor | Good Primary Conductor | Minimal (High Resistance) |

As you can see, mild steel’s conductivity is only about 10% that of copper. This means for the same dimensions, a mild steel wire would have roughly 10 times the electrical resistance of a copper one. This high resistance causes significant energy loss in the form of heat (known as Joule heating), making mild steel completely unsuitable for applications like electrical wiring in buildings or power lines.

Interestingly, it is much more conductive than stainless steel. The high concentration of alloying elements like chromium and nickel in stainless steel creates far more disruption for electron flow, giving it a much higher resistivity.

Factors Affecting Mild Steel’s Electrical Conductivity

The conductivity value of mild steel isn’t a single, fixed number. It’s a dynamic property influenced by several factors that you need to consider in your design.

Temperature

For most metals, including mild steel, there’s an inverse relationship between temperature and conductivity. As the temperature of the steel increases, its atoms vibrate more vigorously. This increased thermal agitation makes it much harder for the free electrons to find a clear path, causing more frequent collisions and scattering. The result: as temperature goes up, resistivity increases and conductivity goes down. This is a critical consideration in high-temperature environments or in components where the current flow itself generates significant heat.

Alloying Elements and Impurities

We touched on this earlier, but it deserves emphasis. Any element present in the iron that isn’t iron is an impurity from an electrical perspective. While alloying elements like manganese (Mn) and silicon (Si) are added to improve mechanical properties like strength and deoxidization, they invariably increase electrical resistivity. Even minute amounts of phosphorus (P) and sulfur (S), which are often considered undesirable impurities, contribute to electron scattering.

This is why specialized electrical steel laminations, which are designed for applications like transformers and motor cores, are carefully controlled. For instance, silicon steel laminations are intentionally alloyed with silicon because, while it increases resistivity (which is good for reducing eddy currents), it also dramatically improves magnetic properties. The trade-offs are always calculated.

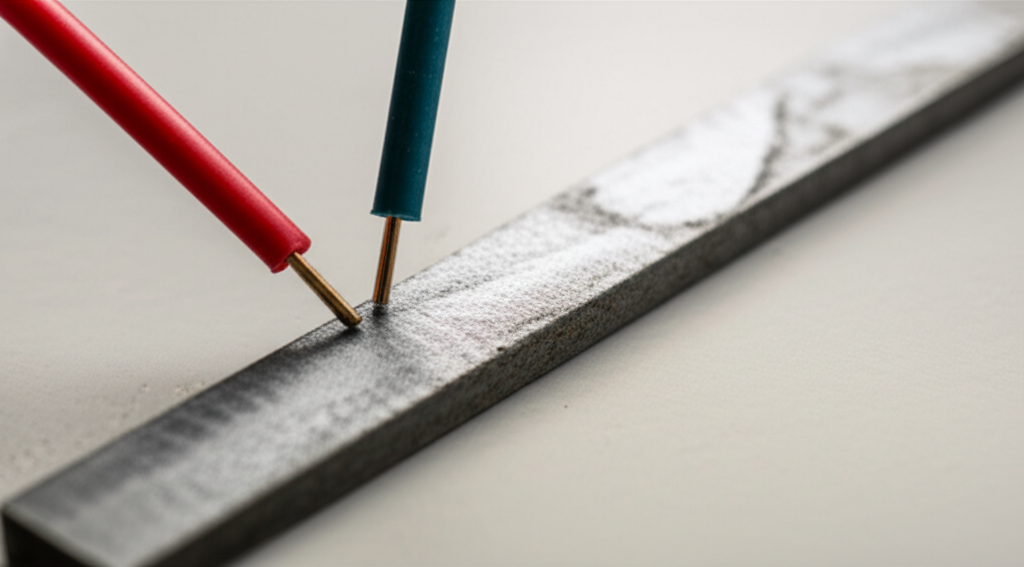

Surface Conditions (Rust and Coatings)

This is perhaps the most critical real-world factor. Mild steel rusts. Rust, or iron oxide, is a ceramic material—and a very effective electrical insulator. A clean, polished piece of mild steel may have predictable conductivity but a layer of rust can completely break an electrical circuit.

This has massive implications for grounding applications. A grounding rod or a structural beam used for earthing can become completely ineffective if its connection point corrodes. The rust layer will prevent a low-resistance path to the ground, creating a serious safety hazard. Likewise, any non-conductive coating like paint, powder coating, or plastic will act as an insulator, and you’ll need to remove it at connection points to ensure electrical continuity.

Cross-Sectional Area and Length

Finally, the basic principles of electricity apply. Just like a wider pipe allows more water to flow, a conductor with a larger cross-sectional area offers less resistance. Conversely, a longer conductor offers more resistance because the electrons have a longer, more arduous journey. This is described by the formula for resistance: R = ρ * (L/A), where ρ is the resistivity, L is the length, and A is the cross-sectional area. When using steel as a conductor, such as for a grounding strap, you must ensure it’s thick enough to handle the potential fault current without overheating.

Practical Applications of Mild Steel’s Electrical Conductivity

Despite its relatively poor performance compared to copper, mild steel’s unique combination of strength, low cost, and moderate conductivity makes it the ideal choice for several important electrical applications.

Grounding and Earthing Systems

This is a primary application. In electrical safety systems, a grounding or earthing path provides a safe route for fault currents to dissipate into the earth, preventing electric shock and equipment damage. This path doesn’t need to be hyper-efficient like a power line; it just needs to be low-resistance enough to be the path of least resistance.

Mild steel is perfect for this. It’s strong enough to be driven into the ground as grounding rods and it’s inexpensive enough to be used extensively. The steel frame of a large building is often bonded together and connected to the main grounding system, turning the entire structure into a part of the safety grid. Its conductivity is more than sufficient for this purpose, provided the connections are kept clean and free of corrosion.

Electrical Enclosures and Conduits

Mild steel is the workhorse material for electrical cabinets, panels, and conduits. Here, its properties serve two functions:

Structural Components and Frames

In machinery and buildings, the steel frame is inherently conductive. While not a primary design feature, this property must be managed. For safety, all metallic frames and structures near electrical systems must be properly bonded and grounded. This ensures that if a live wire accidentally touches the frame, the current will trip a circuit breaker instead of turning the structure into an electrocution hazard.

Welding Electrodes

In many forms of arc welding, a mild steel consumable electrode is used. The welding machine passes a high current through the electrode to the workpiece, creating an electric arc that melts both the electrode and the base metal to form a weld. The electrode’s ability to conduct this high current is fundamental to the entire process.

Electrical Safety Considerations with Mild Steel

Because mild steel conducts electricity, you must handle it with the same respect you’d give any conductive material in an electrical environment.

Proper Grounding is Crucial

This can’t be overstated. Any mild steel component, from a small bracket to a massive I-beam, that has the potential to become energized must be connected to a reliable equipment ground. This is a non-negotiable rule of electrical safety, codified in standards like the National Electrical Code (NEC). An ungrounded steel frame that accidentally gets energized is a hidden and lethal danger.

Corrosion and Its Impact

As discussed, rust is an insulator. A safety ground is only as good as its connections. Regular inspection and maintenance of grounding points on steel structures are essential, especially in corrosive or outdoor environments. A bolted connection that was perfectly conductive on day one could be dangerously resistive after a few years of exposure to moisture. Using conductive pastes or listed hardware for grounding connections can help mitigate this.

Not for Primary Conductors

It’s worth repeating: do not use mild steel for primary electrical wiring. Its high electrical resistance means it will waste a tremendous amount of energy as heat. This heat buildup can be a fire hazard and the voltage drop over any significant length will be unacceptable for powering equipment. The correct materials for this job are copper and aluminum, period. Using mild steel is both inefficient and unsafe. Even in specialized electrical components, like a transformer lamination core, the core is made of a material like silicon steel for its magnetic properties, while the windings that carry the current are made of copper. The same principle applies to motor core laminations where efficiency is paramount.

Key Takeaways: Mild Steel is a Conductor, But with Caveats.

So, where does this leave us? Mild steel’s relationship with electricity is nuanced. Answering the initial question requires looking beyond a simple “yes.”

Let’s recap the essential takeaways for any engineer or designer:

- Yes, It Conducts: Mild steel is a metallic conductor due to the “sea” of free electrons in its atomic structure. It will readily allow current to flow.

- It’s a “Fair” Conductor at Best: Its conductivity is only about 8-14% that of copper. This makes it highly inefficient for transmitting power due to high resistive losses.

- Context is King: Its value lies in applications where its mechanical strength and low cost are the primary requirements, and its conductivity serves a secondary role—be it for safety grounding, structural bonding, or electromagnetic shielding.

- Beware of Rust: Corrosion is the arch-nemesis of mild steel’s conductivity. Rust is an insulator and can render safety-critical grounding connections useless.

- Safety First: Always assume any mild steel structure or component can become electrically live. Proper grounding isn’t just a good idea; it’s a fundamental safety requirement.

By understanding these principles, you can confidently leverage mild steel’s properties to your advantage, making informed decisions that lead to safe, reliable, and cost-effective designs.