How Do Motors Work? Motor Lamination Physics Every Engineer Should Know

Every design engineer faces the same fork in the road. You need higher motor efficiency yet you also need to control cost, manage heat, hit noise targets, and keep lead times reasonable. You open the spec and see choices everywhere: lamination thickness, steel grade, insulation class, stacking method, stamping versus laser, skew angle, rotor bar geometry. You know laminations sit at the heart of your stator and rotor. You also know they quietly decide your torque, back EMF, losses, and even how your procurement plan shakes out. This guide explains the physics behind those decisions and shows you how to choose materials and processes with confidence.

If you’ve ever wondered how lamination thickness affects eddy currents, why hysteresis losses change with alloy and coating, or which manufacturing flow best fits your volume and tolerance needs, you’re in the right place.

In This Article

- Why Lamination Choice Drives Efficiency and Cost

- The Physics Behind Laminations: Eddy Currents, Hysteresis, and Magnetic Circuits

- Material Considerations: Silicon Steel, Cobalt Alloys, and Amorphous Options

- Manufacturing and Assembly Processes: Stamping, Laser, Bonding, and Interlocking

- Application Fit: Induction, BLDC, PMSM, Servo, Stepper, and Transformers

- Performance and Control Implications: Torque, Back EMF, VFDs, and Thermal Management

- Procurement and Quality: Cost Drivers, Tolerances, and Supplier Questions

- Engineering Takeaways and Next Steps

Why Lamination Choice Drives Efficiency and Cost

Let’s start with the problem. Motors convert electrical energy into mechanical energy. They do it through electromagnetic fields and forces. That conversion never happens perfectly since the core “wants” to waste some input as heat. Two culprits lead the charge: eddy current loss and hysteresis loss. Laminations break up eddy currents and lower hysteresis loss. Thickness, grade, and insulation shape the outcome.

- Thin laminations cut eddy current paths. Think of eddy currents as little whirlpools of electrons driven by changing magnetic fields. Thinner insulated layers turn big whirlpools into small ripples.

- Low-loss alloys shrink hysteresis. The hysteresis loop (the B-H curve) tells you how much energy you lose per magnetization cycle. Alloys with low coercivity (resistance to demagnetization) and optimized grain structure waste less energy.

Your lamination stack dominates core losses which in turn drive copper losses, thermal management, and power density decisions. It affects torque-speed characteristics, back EMF, efficiency, and even audible noise and vibration through magnetostriction and mechanical resonance. Good lamination engineering pays for itself across the whole motor lifecycle.

Engineers, product designers, and procurement managers ask the same questions:

- Which material delivers the right performance per dollar at my operating frequency?

- How thin should I go before manufacturing cost and handling risk outweigh loss reduction?

- Should I stamp or laser cut? When does interlocking beat bonding?

- How do stator and rotor lamination tolerances influence torque ripple, vibration, and noise?

We’ll answer these head on.

The Physics Behind Laminations: Eddy Currents, Hysteresis, and Magnetic Circuits

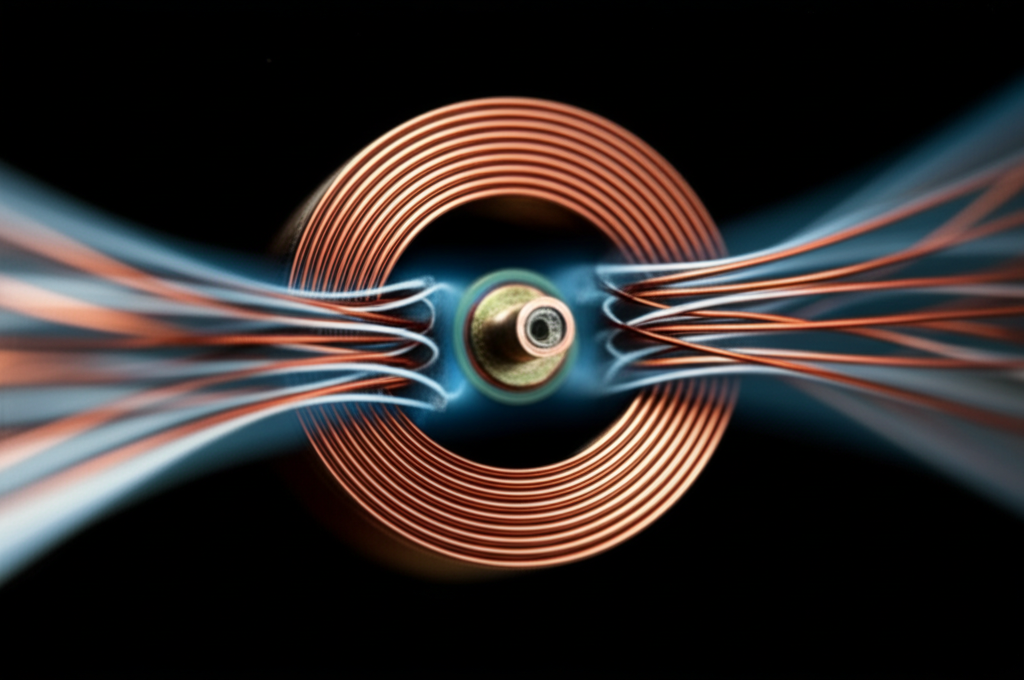

Every motor rides on common physics. Maxwell’s equations set the stage. Ørsted showed that current produces a magnetic field. The Right-Hand Thumb Rule gives field direction around a current-carrying conductor. The Lorentz force explains why a current in a magnetic field feels a force. Fleming’s Left-Hand Rule helps you visualize the torque direction in a DC machine. Faraday’s Law of Induction shows how changing magnetic fields induce voltage and current. These laws are not trivia. Laminations exist because of them.

Electromagnetism and Magnetic Circuits

A stator’s windings create magnetomotive force (MMF). That MMF pushes magnetic flux through a magnetic circuit formed by stator teeth, yoke, air gap, rotor, and back through the return path. Magnetic permeability tells you how easily the material lets flux through. High permeability is like a sponge soaking up water. Magnetic reluctance is the flip side. It resists flux flow the way a narrow pipe resists water flow.

You shape flux with slot geometry, tooth width, air gap length, and lamination grade. You want high flux density where it creates useful torque and limited saturation where flux runs out of room. Saturation hurts efficiency and increases harmonics. Laminations help you hit that sweet spot since they enable high-permeability paths with manageable losses.

Why Eddy Currents Form and How Laminations Stop Them

Faraday’s Law says a changing magnetic field induces an EMF. In a solid core, that EMF drives circulating currents that make heat. These are eddy currents. Their magnitude grows fast with thickness. For a given frequency and flux density, eddy current loss scales roughly with the square of lamination thickness and with the square of frequency. Double the thickness and you get about four times the eddy loss. Increase frequency and those losses climb steeply.

Insulated laminations slice the core into thin plates. Each layer sees the changing flux yet the insulation blocks big loops of current that would otherwise flow through the thickness. Thinner laminations and higher resistivity materials shrink those loops and the heat they generate.

Hysteresis Loss and the B-H Loop

Hysteresis loss happens because a magnetic material doesn’t flip its domains freely. It takes energy to reverse magnetization every cycle as the flux swings. The B-H loop area equals the energy lost per cycle. Materials with low coercivity and narrow loops lose less energy. Silicon additions in steel lower hysteresis loss and raise electrical resistivity. Grain orientation and annealing tune the microstructure which reshapes that loop.

Back EMF, Torque, and the Air Gap

As the rotor turns through the stator field, Faraday’s Law bites again. Motion in a magnetic field induces a voltage that opposes the applied voltage. This back EMF rises with speed and limits current draw at high RPM. It also sets your torque-speed curve since torque roughly scales with current while speed pushes current down via back EMF. Laminations influence back EMF through magnetic flux, stator tooth shape, rotor geometry, and overall magnetic circuit design.

Torque comes from the Lorentz force on conductors and the interaction of magnetic fields. You can write torque as proportional to the product of magnetic flux, current, and effective armature length or, in field terms, as the interaction of stator and rotor MMF. Laminations let you achieve high flux density without unacceptable core losses. That gives you higher torque per amp and better power density.

Induction Motor Physics in a Nutshell

In an induction motor, three-phase currents in stator windings create a rotating magnetic field (RMF). That RMF sweeps past rotor bars and induces currents in them. Those rotor currents create their own field which fights the cause per Lenz’s law. The rotor “chases” the stator field yet it never quite catches up at load. That lag is slip. Synchronous speed depends on supply frequency and pole count: ns = 120f/p. Laminations are vital here since both stator and rotor see changing fields at line frequency and at slip frequency. Eddy current and hysteresis losses multiply without proper lamination thickness and coatings.

Stepper, BLDC, PMSM, SRM, and Universal Motor Notes

- BLDC and PMSM motors use permanent magnets on the rotor and driven stator fields to create torque. Back EMF shape and harmonic content depend on lamination geometry and slot/pole configuration. Laminations lower loss at switching frequencies used by power electronics and variable frequency drives.

- Stepper motors rely on discrete steps created by toothed stator and rotor structures. Laminations control flux path sharpness, detent torque, and efficiency.

- Switched reluctance motors (SRM) drive torque through changing reluctance. Steel saturation and lamination thickness dominate performance and noise.

- Universal motors run from AC or DC. Laminations limit AC losses and keep temperature in check at high speed.

Across all types, laminations shape magnetic flux density, flux linkage, inductance, torque ripple, and acoustic signature. You feel their impact in efficiency, thermal behavior, and control dynamics.

Material Considerations: Silicon Steel, Cobalt Alloys, and Amorphous Options

Your material choice is where physics meets procurement. You control eddy currents with thickness and resistivity. You control hysteresis with alloy, grain structure, and annealing. You balance all that against cost, availability, and manufacturability.

Silicon Steels for General-Purpose Motors

Non-oriented silicon steel (often called M-grades) is the workhorse for motors and generators. It offers:

- Pros: Good magnetic permeability, lower hysteresis loss than plain carbon steel, higher electrical resistivity to reduce eddy currents, widely available supply chain, competitive cost.

- Cons: Losses rise with frequency which limits high-speed or high-frequency performance without going very thin.

Typical thickness ranges include 0.35 mm, 0.30 mm, and 0.27 mm for industrial motors. High-efficiency designs push to 0.20 mm or thinner. Thinner saves loss yet increases cost and handling risk.

If you want a concise overview of options and trade-offs, see this reference on electrical steel laminations. It covers how silicon content, coating type, and gauge influence loss and manufacturability.

Cobalt-Iron Alloys for High Power Density and High Frequency

Cobalt-iron alloys deliver higher saturation flux density than silicon steel. That lets you run higher flux without saturation which boosts torque density. Cobalt grades also improve performance at elevated frequencies due to optimized microstructure and resistivity. You see them in aerospace actuators, high-speed spindles, and advanced PMSM and BLDC machines.

- Pros: High magnetic flux density, strong performance in high-power-density applications, better high-frequency loss profile compared to standard M-grades.

- Cons: High cost, tighter processing requirements, harder on tooling.

Amorphous and Nanocrystalline Materials

Amorphous metals and nanocrystalline alloys offer very low core losses at high frequency thanks to ultra-thin ribbon thickness and unique structure. They shine in transformers and specialized high-speed machines. They’re brittle and tricky to process though. You can’t always stamp them easily. Bonded or cut-and-stack processes can work for prototypes or niche designs.

What About Grain-Oriented Steel?

Grain-oriented silicon steel (CRGO) focuses on transformers that run at near constant flux direction. Motors see rotating fields. That rotation erases many benefits of oriented grain unless your design exploits it in a very specific way. For most motors, non-oriented grades (CRNGO) make more sense.

Key Magnetic Properties to Watch

- Permeability: How much flux you can drive per unit MMF.

- Coercivity: The field needed to demagnetize. Lower coercivity cuts hysteresis loss.

- Remanence: The residual magnetization after field removal. It shapes hysteresis behavior.

- Core loss curves versus frequency and flux density: Real data beats assumptions. Use supplier curves based on IEC 60404 tests where possible.

- Saturation flux density: Higher saturation allows higher torque density before the B-H curve flattens.

- Resistivity: Higher resistivity reduces eddy currents at a given thickness.

Define terms clearly in your doc set. It avoids confusion later in procurement and test.

Manufacturing and Assembly Processes: Stamping, Laser, Bonding, and Interlocking

How you make laminations matters as much as what they’re made of. Different manufacturing routes drive tolerances, burr height, cost, and magnetic performance.

Stamping: The High-Volume Workhorse

You design and build a progressive die, then punch silicon steel coils into shapes at speed. For high volumes and repeatable geometry, nothing beats stamping.

- Pros: Low piece cost at volume, consistent burr control with good tooling, fast cycle times, high repeatability.

- Cons: Upfront die cost, limited flexibility for design changes, potential for burrs that raise interlaminar shorts and increase loss.

Keep an eye on burr height and direction. Burrs that bridge insulation reduce effective stack resistance which increases eddy currents. Specify maximum burr height and call out deburring or tumble if needed. Verify stack factor since it dictates how many laminations fit a stack height.

Laser Cutting: Flexible and Precise for Prototypes and Complex Shapes

Fiber lasers cut intricate profiles and speed up iteration. Perfect for prototype BLDC stators with unusual slot shapes or small pilot runs.

- Pros: No die cost, quick changeovers, excellent dimensional control, ideal for complex geometries or variable skew.

- Cons: Heat-affected zones can degrade magnetic properties if you don’t anneal. Slower than stamping for large runs. Higher per-part cost.

Laser edges may need stress relief annealing to recover magnetic permeability and reduce hysteresis. Work with your supplier on a post-cut anneal schedule aligned with alloy specs.

Wire EDM and Waterjet

EDM gives pristine edges with minimal burrs. It’s slow. Waterjet avoids thermal effects though it struggles to hold the same edge quality on very thin gauges. Both fit niche cases.

Stacking Methods: Interlocking, Bonding, Welding, and Clamping

- Interlocking: Tabs and notches click together like LEGO bricks. You get structural integrity without adhesive or weld heat. Great for many stators and rotors. It can raise local flux leakage if tab geometry isn’t tuned.

- Bonding: Adhesive between laminations creates a rigid, quiet stack. Bonded stacks reduce vibration and noise which helps servo and EV applications. Adhesive adds cost. Cure schedules add time.

- Welding: Spot or seam welding secures stacks fast. The heat-affected zone can hurt magnetic properties near the weld. Use sparingly and away from high-flux regions when possible.

- Cleating or Riveting: Mechanical fasteners hold stacks. Good for serviceability or certain rotor stacks. Adds mass and potential imbalance if not symmetric.

Stress Relief and Annealing

Forming, stamping, or laser cutting introduces residual stress. Stress raises coercivity and hysteresis loss. Post-process annealing recovers properties. Follow alloy-maker guidance. Lean on standards like ASTM A677 or IEC 60404 for property measurement and process verification. You can’t skip this step in performance-critical designs.

Insulation Coatings and Stack Factor

Interlaminar insulation keeps eddy currents from hopping between plates. Common coatings include inorganic phosphate types and organic films rated for temperature class. Specify voltage withstand, adhesion, and thickness. More insulation lowers stack factor which reduces the amount of metal per stack height. You trade small loss reductions against a slightly larger stack or lower flux. Balance it in the mechanical and thermal model.

Skew and Rotor Bar Geometry

In induction machines, rotor bar skew lowers cogging and torque ripple. It can reduce harmonic losses and acoustic noise. Skew adds manufacturing complexity. The sweet spot depends on slot/pole combination and target torque-speed characteristics.

For squirrel cage rotors, rotor bars and end rings set rotor resistance. That resistance shapes slip at load and thus torque speed behavior. Laminated rotors with properly insulated stacks cut core losses at slip frequency and improve efficiency.

If you want a concise primer on the stack itself and why geometry matters, skim the overview of motor core laminations. It will help you align manufacturing choices to your electrical goals.

Application Fit: Induction, BLDC, PMSM, Servo, Stepper, and Transformers

Not every lamination solution fits every motor. Let’s match common architectures with lamination choices.

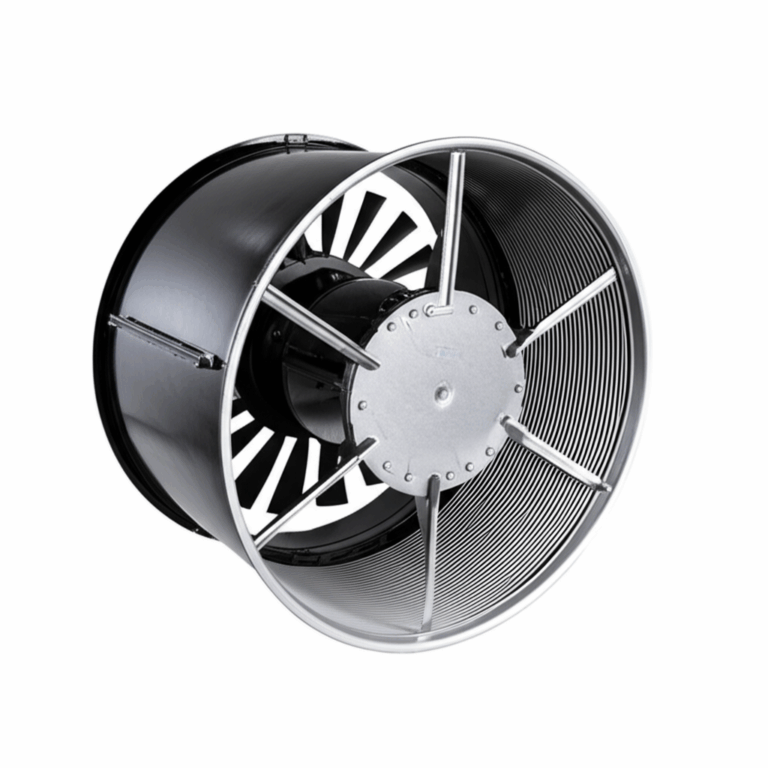

Induction Motors (Single-Phase and Three-Phase)

- Physics: Rotating magnetic field in stator. Induced current in rotor. Slip delivers torque.

- Lamination Focus: Low core losses at line frequency. Robust stator teeth that hold slot liners and handle thermal cycling. Laminated rotors to reduce rotor core and stray losses. Skew to reduce noise and torque ripple.

- Materials: CRNGO silicon steels with thickness around 0.35 mm to 0.27 mm for industrial motors. Push thinner if efficiency mandates it and your process can hold burrs low.

Explore specific component considerations for rotor core lamination when your design needs tighter slip control or reduced harmonic losses.

BLDC and PMSM Motors

- Physics: Permanent magnets on rotor. Electronic commutation creates stator fields. Back EMF shape drives control strategy and torque ripple.

- Lamination Focus: Thin laminations curb switching-frequency eddy currents. Tooth shape and slot fill factor guide flux linkage and inductance. Low-loss steels help at high electrical frequencies in high-speed designs. Bonded stacks can cut acoustic noise in EV and robotics.

- Materials: High-grade silicon steels or cobalt alloys for high power density. Consider 0.20 mm or thinner laminations for high-speed applications.

If you’re deep in BLDC prototyping with nonstandard slot shapes or skew, laser-cut short runs can speed iteration. For end-product volumes, stamping and interlocking often win on cost and consistency.

Servo Motors

Servo drives push frequent accelerations and decelerations. Core losses and copper losses both matter. Low inertia helps dynamic response. Thin laminations reduce loss at the higher electrical frequencies produced by field-oriented control and high PWM rates. Bonded stacks and tight tolerances help minimize torque ripple and audible noise.

Stepper Motors

Teeth define step size and holding torque. Lamination accuracy sets detent torque and smoothness. Magnetic flux density and reluctance changes drive torque. High-precision stamping or laser cutting make a difference because geometry repeats with every step.

Universal Motors

They run on AC or DC. Laminations limit AC losses at high speed. Brush and commutator components define maintenance cycles. Laminations must manage heat since these motors often run hot due to copper and core losses.

Transformer Cores

Not a motor, yet closely related. Transformers use laminations to reduce eddy current and hysteresis losses at line frequency. If you’re managing both motors and transformers, the physics aligns. If you need a quick refresher, this overview of transformer lamination core helps you link material choices across product portfolios.

Stator vs Rotor Focus Areas

- Stator: Slot geometry, tooth tips, yoke thickness, and insulation all shape magnetic flux density, torque production, and noise. Sizing and stack factor affect available copper window which hits copper loss and thermal rise.

- Rotor: For induction motors, rotor bar geometry and lamination skew drive slip and torque ripple. For PMSM and BLDC, rotor back iron thickness supports magnet flux without saturating while minimizing mass.

If you want to dig deeper into stator options, see stator core lamination for a component-level view that ties geometry to performance and manufacturability.

Performance and Control Implications: Torque, Back EMF, VFDs, and Thermal Management

You don’t pick laminations in a vacuum. They interact with control strategy, power electronics, and mechanical packaging.

Torque-Speed Characteristics and Slip

Torque-speed curves express the balance between applied voltage, back EMF, winding resistance, and core losses. Laminations determine magnetic flux and therefore back EMF constants. In induction motors, rotor and stator lamination losses change with slip and frequency. A small change in core loss can shift temperature which in turn changes winding resistance and torque under load.

Back EMF and Inductance

With BLDC and PMSM, you tune back EMF constant (Ke) and phase inductance to fit your inverter voltage and current limits. Laminations influence both. Higher permeability and careful tooth geometry increase flux linkage. That boosts back EMF and torque per amp. It also changes inductance which affects current ripple under PWM. Good lamination design makes your power electronics’ job easier.

Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs) and PWM Effects

VFDs adjust electrical frequency to control synchronous speed in AC motors. High switching frequencies help current control yet raise iron loss due to additional harmonics. Thin laminations and low-loss alloys pay off here. Watch for bearing currents and common-mode voltage that can create stray losses. Grounding and filtering help.

Thermal Management and Efficiency

Core losses become heat. Joule heating in copper adds more. Mechanical losses from bearings and windage finish the picture. Your lamination decision reduces the heat you must carry away with the housing, airflow, liquid cooling, or heat sinks. Lower core loss reduces steady-state temperature and extends insulation life. That pays back in reliability and service intervals.

Acoustic Noise and Vibration

Magnetostriction in laminations can create a humming tone. Slot harmonics and torque ripple add chatter. Bonded stacks, skewed rotors, and optimized tooth shapes reduce noise. Better laminations improve vibration behavior since they cut forcing functions at the source.

Reliability and Protection

Motors see overloads, starts, and regenerative events. Laminations handle thermal cycling and mechanical stress as the stack expands and contracts. Insulation integrity protects against interlamination shorts. Steady lamination quality improves protection system accuracy since thermal models rely on predictable loss.

Diagnostics and Failure Analysis

When motors overheat or fail to meet torque targets, look at core loss first, especially after a design change. Check thickness, burr height, coating integrity, and annealing records. Infrared thermography and loss separation tests can isolate whether copper or core losses create the heat. Vibration analysis and noise measurements can indicate lamination looseness or stack defects.

Procurement and Quality: Cost Drivers, Tolerances, and Supplier Questions

You don’t buy laminations by physics alone. You need a supply plan that fits volume, quality, and budget.

Major Cost Drivers

- Material grade and thickness: Thinner gauges cost more and are harder to handle.

- Yield and scrap: Nesting efficiency and coil width utilization matter.

- Tooling: Progressive dies cost money and time yet deliver low run-rate cost.

- Secondary processes: Deburring, bonding, annealing, and coating add cost and schedule.

- Inspection and quality: Tight tolerances and full PPAP or APQP deliver confidence with some cost.

Tolerances That Matter Most

- Tooth width and slot opening: These affect flux density and slot fill.

- Stack height and stack factor: These determine copper window and magnetic path length.

- Burr height and direction: These influence interlaminar shorts and eddy current loss.

- Roundness and concentricity: These affect air gap uniformity and torque ripple.

- Insulation class and coating thickness: These determine interlamination resistance and temperature capability.

Quality and Standards

Ask for material certifications with core loss and permeability test data per IEC 60404 methods. Confirm annealing cycles and coating specs. For tooling, request capability studies on tooth width and burr height. If you build safety-critical systems, request PPAP elements like process flow, FMEA, control plans, and gauge R&R.

Supplier Questions to Ask

- Which silicon steel grades do you stock and at what thicknesses? What are typical lead times?

- How do you control burr height on high-speed stamping lines?

- What annealing schedules do you support for laser-cut or stamped parts?

- What stack assembly methods do you recommend for my volume and noise target?

- Can you provide loss versus frequency data at my target flux density?

- How do you verify interlamination resistance and stack factor?

- What is your experience with EV-grade BLDC stators or high-speed spindles?

If you’re scoping a new program and want a simple starting point, review the range of motor core laminations to align options with your application’s torque, speed, and cost targets.

What’s Really Going On Inside the Motor: A Fast Refresher

Before you lock a spec, it helps to refresh how the hardware creates torque. It keeps everyone aligned from design through procurement.

Stator and Rotor Roles

- Stator: The stationary core carries the windings that create the working magnetic field. Laminations minimize eddy currents as the field changes with AC supply or inverter-driven waveforms.

- Rotor: The rotating core interacts with that field. In induction motors, rotor bars carry induced currents that produce torque. In PMSM and BLDC, rotor magnets interact with stator fields. In DC motors, the armature windings on the rotor see commutated current via brushes and a commutator.

For a component-focused summary, see this concise overview of stator core lamination. It highlights how the stationary core sets the stage for flux paths and copper utilization.

DC Motor Snapshot

Apply voltage to the armature windings inside a magnetic field and the Lorentz force pushes on the conductors. That creates torque. As the rotor spins, the commutator flips current every half turn so torque keeps the same direction. Back EMF rises with speed and limits current. Laminations keep core losses in check as current reverses rapidly under load and as the field changes in each slot.

Induction Motor Snapshot

Feed the stator with three-phase AC and you get a rotating magnetic field. It induces rotor currents through Faraday’s Law. Those currents interact with the stator field and produce torque. The rotor lags the stator field slightly which is slip. Laminations in stator and rotor keep losses low at line frequency and at slip frequency.

BLDC and PMSM Snapshot

The inverter sends controlled AC into the stator windings. The rotor’s permanent magnets follow the rotating stator field. Electronic commutation replaces mechanical brushes. Laminations minimize high-frequency core loss driven by PWM and electrical frequency. The result is high efficiency, high torque density, and precise control with field-oriented control.

Practical Design Levers You Can Pull

Tie the physics back to knobs you can actually turn.

- Lamination thickness: Thinner reduces eddy current loss especially at higher frequency. It raises cost and manufacturing complexity. Good choice for high-speed PMSM or BLDC and premium efficiency induction motors.

- Alloy selection: Standard CRNGO silicon steel for general-purpose. Higher-grade steels or cobalt for high power density and frequency. Amorphous for specialized high-frequency uses.

- Insulation coating: Specify interlamination resistance, temperature class, and compatibility with bonding or interlocking. Confirm stack factor impact.

- Tooth geometry and slot design: Influence flux density, saturation, copper fill, inductance, and torque ripple. Use FEA to guide trade-offs.

- Skew and pole-slot combination: Reduce cogging and acoustic noise. Watch efficiency trade-offs.

- Assembly method: Interlocking for volume and robustness. Bonding for noise and rigidity. Welding for speed yet keep heat zones away from high-flux regions when possible.

- Annealing: Recover magnetic properties after cutting or stamping. Don’t skip it on critical parts.

Common Missteps and How to Avoid Them

- Chasing ultra-thin laminations without tooling and handling plans. You end up with bent parts, high scrap, and longer lead times.

- Ignoring burr height. Small burrs can become big losses when they short layers together.

- Underestimating the impact of coatings on stack factor. You lose window area and then struggle to hit copper fill and temperature rise targets.

- Skipping stress relief. Residual stress raises hysteresis loss and wrecks your predicted efficiency.

- Picking CRGO for motors without a specific reason. It’s great for transformers. It’s usually not the right choice for rotating flux.

- Forgetting rotor core losses. Stators get the attention. Rotors still heat up and set thermal limits in induction machines.

Real-World Impacts You Can Measure

- Efficiency: Better laminations can boost full-load efficiency by several tenths of a percent in industrial motors. That sounds small. It’s not when you multiply by thousands of hours and utility rates.

- Thermal Headroom: Lower core loss drops winding temperature rise. That extends insulation life and reduces failures.

- Acoustic Performance: Bonded stacks and optimized skew reduce tonal noise. Customers notice.

- Power Density: Higher saturation materials and thin laminations let you cut mass and size at the same torque. That matters in EVs, drones, and robotics.

Your Engineering Takeaway

Here’s the distilled playbook.

- Nail the physics:

- Eddy current loss drops with thinner laminations and higher resistivity alloys.

- Hysteresis loss drops with low coercivity and proper annealing.

- Laminations set flux paths which shape torque, back EMF, and efficiency.

- Choose material on application:

- CRNGO silicon steel for most motors at 50/60 Hz and inverter drives.

- Cobalt alloys for high power density or high frequency.

- Amorphous only when your process and frequency justify it.

- Match process to volume:

- Stamping for volume and cost.

- Laser for prototypes and complex shapes. Anneal to recover properties.

- Interlocking for structural simplicity. Bonding for low noise and stiffness.

- Control the details:

- Specify burr height, stack factor, insulation class, and anneal.

- Verify loss curves at your frequency and flux density.

- Use skew and tooth geometry to manage torque ripple and noise.

- Plan procurement smartly:

- Align thickness and grade with supplier capability and lead time.

- Ask for IEC 60404 test data and process controls.

- Balance piece price with lifecycle efficiency savings.

When you put these steps together, you don’t just buy laminations. You buy efficiency, thermal headroom, quieter operation, and predictable performance.

Next Steps: Empower Your Design and Sourcing

- Define your operating points: electrical frequency range, flux density targets, torque-speed envelope, and thermal limits.

- Pick a starting material: choose an M-grade silicon steel and a target thickness based on frequency. Move thinner only if efficiency gains outweigh cost and complexity.

- Lock key specs into your drawing:

- Lamination thickness, coating type, and insulation class.

- Max burr height and stack factor range.

- Required anneal and allowable assembly methods.

- Validate with quick-turn samples:

- Use laser-cut laminations for fit and FEA correlation. Anneal after cut.

- Measure core loss at operating flux and frequency. Confirm against supplier data.

- Prepare for production:

- Engage a stamping supplier early. Review die design, grain direction assumptions for non-oriented steel, and inspection plans.

- Choose bonding or interlocking based on noise targets and volume.

If you need a single reference page to ground your team’s discussion on component scope and trade-offs, share this overview of motor core laminations as a common baseline. Then align stator and rotor requirements with component-specific guidance like stator core lamination and rotor core lamination.

Finally, remember the simple truth behind all of this. Motors move because electric currents and magnetic fields interact. Laminations make that interaction efficient, cool, quiet, and cost effective. Get the laminations right and the rest of the design gets easier.

References and standards to consult as you finalize specs:

- IEC 60404 series for magnetic property measurements and core loss testing methods.

- ASTM standards such as A677 and related documents for electrical steel specifications and processing guidance.

- IEEE publications on motor efficiency, core loss modeling, and variable frequency drive impacts.

Notes:

- The relationships discussed here follow established physics: Faraday’s Law of Induction, Lorentz force, Maxwell’s equations, and standard motor concepts like synchronous speed, slip, and back EMF.

- Efficiency calculations use the classic approach: mechanical output power divided by electrical input power while accounting for copper losses (I²R), core losses (eddy currents and hysteresis), and mechanical losses from friction and windage.

With this framework, you can choose lamination materials and processes that serve your performance goals and your business goals. When you’re ready, bring in your supplier’s engineering team and walk through your frequency, flux, and cost targets together. Good questions lead to good cores which lead to great motors.