How Does a 3 Phase Squirrel Cage Induction Motor Work? | The Complete Guide

Have you ever wondered what makes the modern world run? It’s not magic, but it’s close. It’s a simple, powerful engine called the 3-phase squirrel cage induction motor. These motors are the unseen workhorses in factories, buildings, and machines all around you. But how they work can feel like a complex puzzle. This guide is here to solve that puzzle for you. We’ll break it down step-by-step, using simple ideas to explain the powerful science that keeps our world moving.

Table of Contents

- What is This Industrial Workhorse, Anyway?

- What Are the Main Parts of This Motor?

- How Does the Magic of Rotation Actually Start?

- How Does the Rotor Get Power with No Wires?

- Why Does the Rotor Actually Spin?

- What Is “Slip” and Why Is It So Important?

- Are These Motors Hard to Get Started?

- What Makes These Motors So Great (And What Are Their Flaws)?

- Where Will You Find These Motors in the Real World?

- How Can We Make These Simple Motors Even Better?

What is This Industrial Workhorse, Anyway?

Imagine you need a motor for a big, important job. You need it to be strong, tough, and reliable. You don’t want a machine that needs constant repairs or has a lot of delicate parts. That’s a huge problem for any business. Production could stop, costing you time and money, all because a complicated motor broke down. It’s a real headache.

This is where the 3-phase squirrel cage induction motor comes in. Think of it as the Clydesdale horse of the motor world. It’s an asynchronous motor, which is a fancy way of saying its moving part doesn’t spin at the exact same speed as the magnetic field that powers it. It gets its power from a scientific principle called electromagnetic induction, which we’ll explore soon. It’s a self-starting motor that runs on the type of power most factories use: three-phase alternating current (AC) power.

So, why the funny name “squirrel cage”? It’s because of its main moving part, the rotor. If you took the rotor out and looked at it, its shape would remind you of the spinning wheel you might see in a pet squirrel’s cage. It’s a simple, clever design that makes this motor so tough and popular. In fact, these motors make up about 90% of all motors used in industry today!

What Are the Main Parts of This Motor?

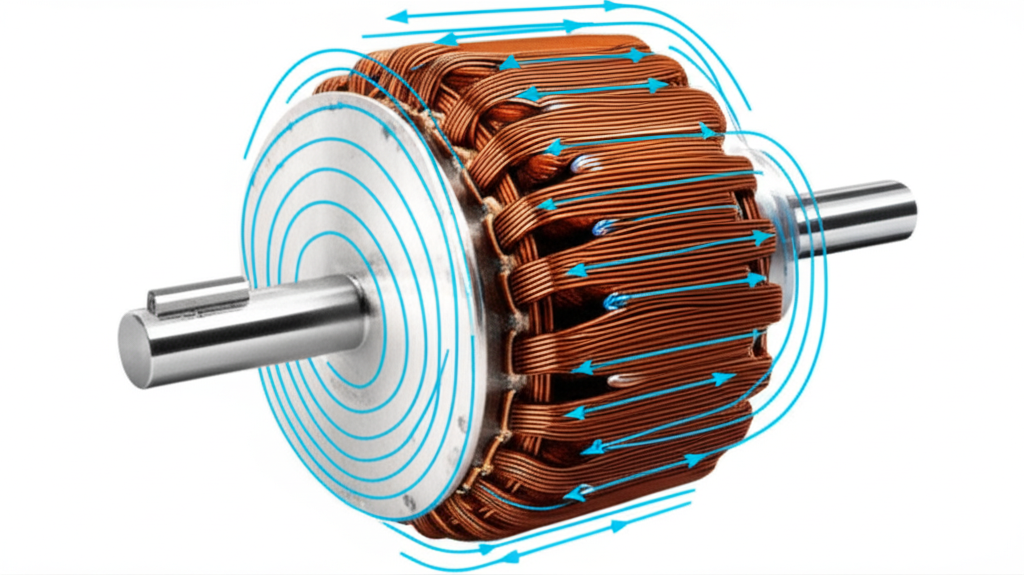

To really understand how something works, you need to know what’s inside. Luckily, a squirrel cage motor has very few parts. It’s built on a simple idea: one part stands still, and the other part spins inside it. These two main parts are the stator and the rotor.

The stator is the stationary, or non-moving, outer part of the motor. It’s a ring made of many thin, stacked layers of high-quality metal. Using thin layers for the stator core lamination is a neat trick that helps reduce wasted energy, which would otherwise turn into heat. Wrapped neatly inside slots in the stator are coils of copper wire. These are the stator windings. When we connect a three-phase power supply to these windings, the stator becomes a powerful electromagnet.

The rotor is the part that rotates. It sits right in the middle of the stator, but it never touches it. The tiny space between them is called the air gap. Just like the stator, the rotor is also made of a laminated core to be more efficient. The “squirrel cage” part consists of heavy bars, usually made of aluminum or copper, running through slots in the rotor. At each end, these rotor bars are connected by end rings, which short-circuits them. This creates a closed electrical path, which is super important for how the motor works. The quality of the rotor core lamination is vital, as it directly influences the motor’s efficiency and performance.

How Does the Magic of Rotation Actually Start?

Here is where the real fun begins. The first step is creating a rotating magnetic field (RMF). A magnetic field is an invisible area of force, like the kind around a fridge magnet. But in a motor, we create a much more powerful one using electricity.

When you send alternating current (AC) through the stator’s three sets of windings, something amazing happens. Because the three currents are slightly out of sync with each other, they create magnetic poles (north and south) that aren’t fixed. Instead, they spin around the inside of the stator at a very high, constant speed. Imagine holding a powerful magnet and spinning it in a circle. That’s exactly what the stator does, but it uses electricity instead of your hand!

This speed is called the synchronous speed. It’s the speed of the magnetic field itself, not the motor. We can figure out this speed with a simple formula: Synchronous Speed (Ns) = (120 x Frequency) / Number of Poles. The frequency is how fast the AC power cycles (usually 60 Hz in the US), and the poles are the magnetic norths and souths created by the windings. This spinning field is the key that unlocks everything else.

How Does the Rotor Get Power with No Wires?

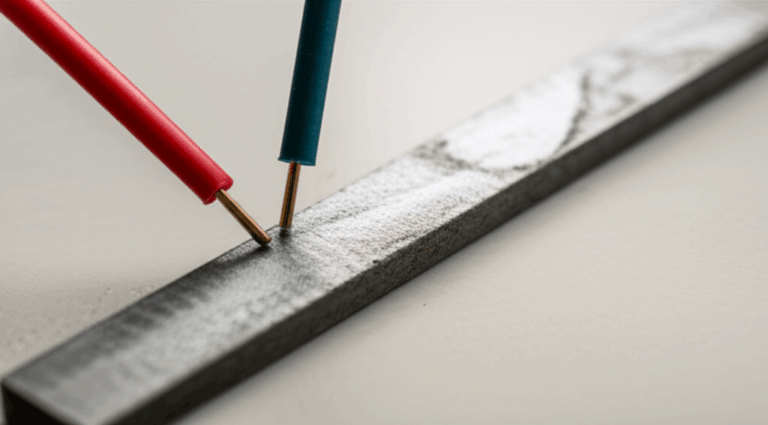

So we have a spinning magnetic field in the stator. But the rotor is just sitting there in the middle, not connected to any power source. How does it get the juice to move? The answer is a brilliant discovery by a scientist named Michael Faraday.

His rule, now called Faraday’s Law of Induction, says that if you move a wire through a magnetic field, or move a magnetic field past a wire, you will create—or “induce”—an electric current in that wire. This is the very same principle used in power plants to generate the electricity for your home.

In our motor, the stator’s powerful rotating magnetic field is constantly sweeping past the stationary bars of the squirrel cage rotor. This moving field “cuts” through the rotor bars, and just as Faraday’s Law predicts, it induces a powerful voltage (called an EMF) and a strong electric current in the rotor bars. Since the bars are connected by end rings, this current flows in a closed loop. The rotor has become an electromagnet without a single wire touching it!

Why Does the Rotor Actually Spin?

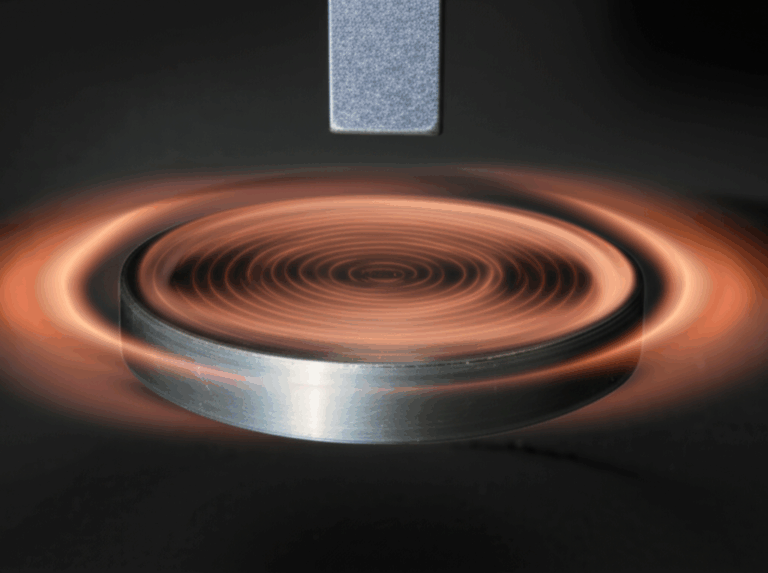

Now we have two magnetic fields: the stator’s RMF and the new one we just created in the rotor. When you put two magnets near each other, they either pull together or push apart. This push and pull is a physical force. In our motor, this force is what creates torque, or the twisting force that makes things spin.

A scientist named Heinrich Lenz figured out an important rule, now called Lenz’s Law. It says that the current induced in the rotor will create a magnetic field that opposes the change that caused it. What does that mean in simple terms? The rotor’s magnetic field will try to stop the stator’s field from sweeping past it. The only way it can do that is to chase after the stator’s field.

Think of it like this: imagine a carrot dangling from a string tied to a stick, held just in front of a donkey. The donkey wants the carrot, so it moves forward to catch it. But as the donkey moves, the carrot also moves, always staying just out of reach. The rotor is the donkey, and the rotating magnetic field is the carrot. The rotor “chases” the RMF, and this chase is what we see as rotation! This turning force on the current-carrying rotor bars is explained by another principle called the Lorentz force.

What Is “Slip” and Why Is It So Important?

Here’s a tricky question: what would happen if the rotor (the donkey) actually caught up to the rotating magnetic field (the carrot)? If the rotor spun at the exact same synchronous speed as the RMF, there would be no relative motion between them. The magnetic field would no longer be “cutting” the rotor bars.

According to Faraday’s Law, if there’s no cutting action, no current is induced in the rotor. If there’s no current in the rotor, it stops being an electromagnet. And if the rotor has no magnetic field, there’s no torque to make it spin. The motor would stop working!

This is why a squirrel cage induction motor is an asynchronous motor. The rotor must always spin slightly slower than the RMF. This difference in speed is called slip. Slip is absolutely essential. It’s the “secret sauce” that allows induction to happen and torque to be produced. For most motors running at full load, the slip is very small, maybe only 2% to 5%. It’s just enough of a difference to keep the magic happening.

Are These Motors Hard to Get Started?

A big advantage of this motor design is that it’s self-starting. As soon as you apply three-phase power, the RMF is created, induction happens, and the rotor starts to spin. It doesn’t need any special tricks to get going.

However, there is one challenge. For the first split second, when the rotor is at a standstill, the slip is 100%. The RMF is cutting the rotor bars at maximum speed, which induces a massive amount of current. This is called the locked rotor current or starting current. It can be 5 to 8 times the motor’s normal running current! This huge surge can cause lights to dim or even trip circuit breakers in a building’s electrical system. This is a real problem for facilities with sensitive equipment.

The agitation comes from worrying about this huge power draw every time a large motor starts. It can put stress on the entire electrical grid of a factory. The solution is to use special starters. A Direct-On-Line (DOL) starter is the simplest, but for bigger motors, engineers use Star-Delta starters or soft starters. These devices reduce the starting voltage, which limits that initial current surge and allows the motor to start up smoothly.

What Makes These Motors So Great (And What Are Their Flaws)?

There’s a reason these motors are everywhere. Their benefits are hard to beat.

Advantages:

- Simple and Rugged: With basically one moving part and no brushes or commutators to wear out, their construction is incredibly robust.

- Low Cost: Their simple design makes them cheaper to manufacture than almost any other motor type.

- Low Maintenance: You just need to make sure the bearings are good and it stays clean. No complex upkeep needed.

- High Efficiency: When running at their rated power, they are very efficient at turning electricity into motion.

Disadvantages:

- High Starting Current: As we discussed, that initial power surge can be a problem for the electrical grid.

- Poor Speed Control (Traditionally): A standard induction motor wants to run at a nearly constant speed. Changing its speed used to be very difficult and expensive.

- Lower Starting Torque: Compared to some other motor types, their initial twisting force isn’t as high, making them less suitable for jobs that need a huge push right from the start, like lifting an elevator.

Where Will You Find These Motors in the Real World?

Once you know what to look for, you’ll see the work of these motors everywhere. Their reliability makes them perfect for jobs that need to run for hours, days, or even years with little fuss.

You’ll find them in all kinds of industrial applications:

- Pumps: Moving water for cities or chemicals in a factory.

- Fans and Blowers: Powering the HVAC systems that keep our buildings comfortable.

- Compressors: Providing compressed air for tools and machines.

- Conveyors: Moving products along an assembly line or luggage at the airport.

- Machine Tools: Running lathes, mills, and grinders with steady power.

They are the backbone of manufacturing, water treatment, and countless other processes that support our daily lives.

How Can We Make These Simple Motors Even Better?

For a long time, the biggest weakness of the squirrel cage motor was its fixed speed. You turned it on, and it ran at one speed. But what if you needed your pump to run slower to save energy? This was a big problem. The agitation was that factories were wasting huge amounts of electricity—and money—by running motors at full speed when they didn’t need to.

The solution came in the form of the Variable Frequency Drive (VFD). A VFD is a smart electronic controller that changes the frequency of the electricity going to the motor. Remember our speed formula? If you change the frequency (f), you change the motor’s synchronous speed. A VFD allows you to control the motor’s speed with incredible precision. This has been a game-changer, allowing these simple motors to be used in complex tasks and saving tons of energy.

Engineers are also constantly improving the efficiency of the motors themselves. They use better materials, tighter tolerances in the air gap, and improved designs for the electrical steel laminations that make up the stator and rotor cores. This has led to international efficiency standards, with ratings like IE1, IE2, IE3 (Premium Efficiency), and IE4 (Super Premium Efficiency). Using a more efficient motor directly translates to lower electricity bills and a smaller carbon footprint.

Here’s a quick look at how important these motors are:

| Aspect | Data/Statistic | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Global Motor Market Share | Squirrel cage induction motors make up 85-90% of all industrial motors. | They are the most common type by far. |

| Industrial Energy Use | These motors use about 70% of all electricity in industry. | Making them efficient is very important. |

| Energy Savings with VFDs | Using a VFD can save 20-50% of the energy used by a pump or fan. | A huge potential for cost and energy savings. |

| Typical Lifespan | A well-maintained motor can last 15 to 25+ years. | They are built to be reliable for a long time. |

| Starting Current | The starting current can be 5-8 times the normal running current. | This is a key challenge to manage. |

Key Takeaways to Remember

The 3-phase squirrel cage induction motor might seem complex, but its working principle is a beautiful dance of physics. Here’s a quick recap of the most important points:

- The Stator Makes a Spinning Field: Three-phase AC power in the stator windings creates a rotating magnetic field (RMF).

- Induction Powers the Rotor: The RMF induces a current in the rotor bars without any physical connection, thanks to Faraday’s Law.

- Magnetic Fields Create Torque: The rotor’s own magnetic field tries to “catch up” to the stator’s RMF, causing the rotor to spin.

- Slip is Essential: The rotor must always spin slightly slower than the RMF. This speed difference, called slip, is what allows the motor to work.

- Simple is Strong: Their rugged design, with few moving parts, makes them reliable, low-cost, and easy to maintain.

- Modern Tech Makes Them Smarter: VFDs have solved the speed control problem, making these motors more versatile and energy-efficient than ever before.