How Does an Electrostatic Motor Work? Unraveling the Principles of Electric Field Propulsion

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What Is an Electrostatic Motor?

- Why Should You Care About Electrostatic Motors?

- How Do Charges and Fields Make Force?

- What Parts Make Up an Electrostatic Motor?

- How Does the Variable Capacitance Principle Create Motion?

- How Do Charge Induction and Dielectric Polarization Work?

- How Do We Turn Force Into Smooth Spinning?

- What Are the Pros and Cons?

- Where Do We Use Electrostatic Motors Today and Tomorrow?

- How Do Electrostatic and Electromagnetic Motors Compare?

- How Do We Stay Safe With High Voltage?

- Can You Build a Simple Electrostatic Motor?

- What Do Control Systems and Power Electronics Do?

- What Does the Future Look Like?

- References

- Summary

Electrostatic motors do not use magnets. They use electric fields to pull and push. In this guide I show you how that works in plain English. You will see the parts. You will see the science. You will see where these motors shine. You also learn how they differ from the motors you see every day.

Introduction

Problem: motors can be loud. They can make heat. They can make magnetic noise that upsets medical tools or space gear. Many do not run well in vacuum. Some fail at tiny sizes.

Agitate: that hurts you if you build robots or medical devices. It hurts you if you want quiet flight or micro machines. You try to shrink a coil yet the losses keep rising. You try to go into space yet the grease outgasses.

Solution: use the power of the electric field. Electrostatic motors convert voltage to motion with almost no magnetic flux. The result can be small. It can be precise. It can work in vacuum. It can run cool at micro scale.

I have built and tested simple models. I have read the papers. I will walk you through the core ideas so you can use them too.

What Is an Electrostatic Motor?

An electrostatic motor uses the electrostatic force to make torque. That force comes from an electric field between parts at different electric potential. When you apply voltage you get a field. When a part with charge or polarization sits in that field it feels a force. The rotor turns because the forces do not cancel.

Think of two plates like a capacitor. Pull them closer and the capacitance changes. The field stores energy. The motor takes some of that stored electrostatic potential energy and turns it into motion. This is electromechanical energy conversion without magnets.

Why Should You Care About Electrostatic Motors?

You may need a motor that does not make magnetic flux. You may need less electromagnetic interference (EMI). You may need a motor that works in vacuum. You may want tiny parts made with MEMS (Micro‑Electro‑Mechanical Systems) on silicon. These are sweet spots for electrostatic designs.

You also get very low current at high voltage. That means low I²R loss. It also means you need strong insulation. In short you trade current for high voltage. At small scale that trade pays off.

How Do Charges and Fields Make Force?

Let’s start simple. Positive and negative charge pull or push. Coulomb’s Law says two charges attract if the signs differ and repel if the signs match. The electric field tells you the force a test charge would feel.

There is a handy rule. Force equals charge times field. We write it as F = qE. A potential difference makes the field. A bigger voltage makes a stronger field. The energy density of an electric field grows with the field squared. So a strong field packs a lot of energy that a motor can tap.

What Parts Make Up an Electrostatic Motor?

Every motor like this has three key parts.

- The stator holds fixed electrodes. It connects to a high voltage supply. It makes a steady or time‑varying field. In some designs it makes a rotating electric field. In others it makes a traveling wave along the rim.

- The rotor is the moving part. It can be conductive. It can be a dielectric material that polarizes. It may carry induced charge. It may be textured like a comb in MEMS gear. Designers explore DC electrostatic motors, AC electrostatic motors, synchronous electrostatic motors, and even stepper electrostatic motor ideas.

- The dielectric medium fills the gap. It might be air, a liquid dielectric, a solid dielectric, or vacuum. The dielectric constant or permittivity tells you how the field behaves. Watch the dielectric strength and breakdown voltage so you do not get arcing or spark discharge. Engineers sometimes use insulating oils to raise strength.

I also see special designs. Some use a permanent charge called an electret. Some use electroactive polymers or electrostriction. Some use frictionless bearings to cut loss. Each choice changes performance and safety.

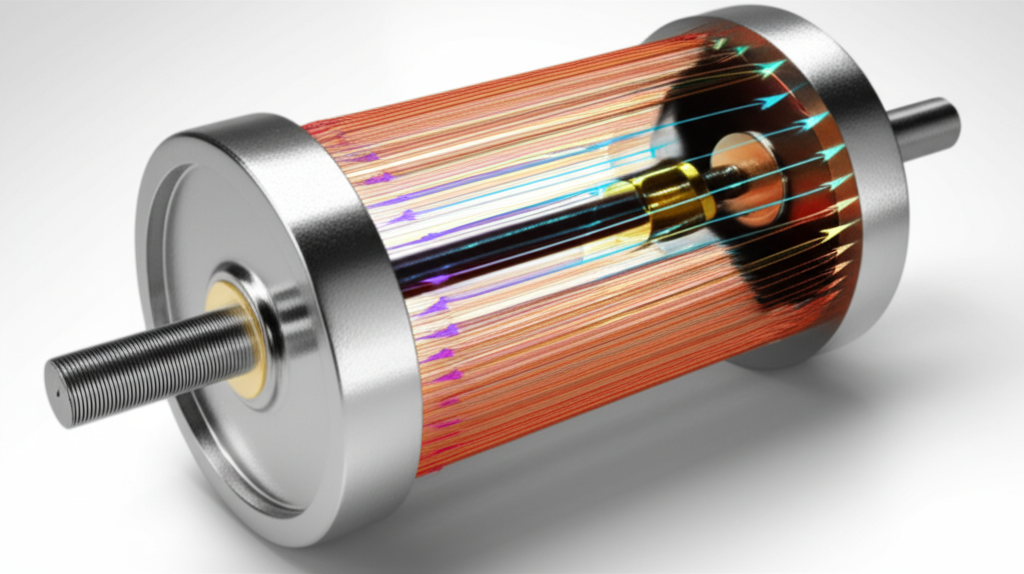

How Does the Variable Capacitance Principle Create Motion?

This is the classic trick. Picture two sets of plates like a variable capacitor. When they line up the capacitance is high. When they are misaligned it is low. The motor pulls toward the high value because that state stores more energy at the same voltage. The pull creates torque.

Designers build planar and cylindrical versions. The rotor teeth chase the stator teeth as the drive switches the electrodes. That change in geometry drives a change in capacitance. The change in capacitance creates force. The force becomes motion. You can scale this down for miniature electrostatic motors in MEMS.

How Do Charge Induction and Dielectric Polarization Work?

In induction type designs you place a neutral conductor in a field. Charges move inside it. The near side gets one sign. The far side gets the other. The near side sees the stronger field. So the net force pulls the rotor toward the stator segment. That is how charge transfer or surface conduction motors can work.

In dielectric polarization motors you place a dielectric in a non‑uniform electric field. The field polarizes the material. The side in the strong field feels more force. So the body moves into the stronger region. That is the base of dielectrophoresis. It links to electrophoretic motors in fluids. It also links to electrostriction and electroactive polymers that change shape when voltage rises.

How Do We Turn Force Into Smooth Spinning?

We need a pattern. We switch the stator electrodes in time. This is commutation. Do it in the right order and the force vector keeps pulling the rotor forward. You can think of it as a traveling wave. The rotor chases the peak. The result is steady spin.

Good control keeps the rotor in step. If the fields move too fast the rotor falls out of synchronization. If they move too slow the torque dips. Pulsed electric fields can help start. High frequency drive can help at speed. With the right control system you get smooth torque and high efficiency.

What Are the Pros and Cons?

Problem: we want motors that fit tiny spaces. We want motors that stay quiet and clean. We want motors that work where magnets do not.

Agitate: you may fight EMI near sensors. You may fight magnetic flux in MRI rooms. You may fight lubrication and outgassing in vacuum. You may fight vibration and noise in haptics.

Solution: electrostatic motors shine in these cases.

Advantages:

- No magnets. Very low magnetic interference. Strong EMI shielding is not always needed.

- Great in vacuum. No iron core loss. Low gas drag. No outgassing from coils.

- High efficiency at micro scale. MEMS electrostatic actuators can reach high speeds with low current.

- Precise position control. Good for precision manufacturing, robotics, and medical devices.

- Can handle extreme temperatures if you choose good polymers or ceramics or use vacuum gaps. You can harden for radiation too.

Disadvantages:

- Needs very high voltage. Often in the kV range.

- Lower torque density at large size than most magnetic motors.

- Risk of dielectric breakdown and arcing. Sensitive to humidity and dust.

- Needs special power electronics for high voltage and high frequency switching.

Where Do We Use Electrostatic Motors Today and Tomorrow?

Today we see strong use in MEMS. Think micro‑robotics, micro‑grippers, and tiny optical switches. Synchronous electrostatic and stepper style drives move micro mirrors by tiny steps. Small forces go a long way when parts are small.

We also see space and lab work. In space exploration you often work in vacuum. You need low EMI. You need radiation hardening. Electrostatic gear fits well. You also see related tech like ion thrusters and ionic wind propulsion. These use electric fields to move ions and air. They are not the same as a motor with a rotor. Yet the electric field propulsion principle is linked.

Looking ahead I see HALE aircraft, quiet drones, and electric vehicle concepts that mix types. I see aerospace actuators and medical tools near MRI suites. I see robotics with soft touch and low vibration. Research at NASA and MIT keeps pushing. So do labs at top schools that publish academic papers and file patents.

How Do Electrostatic and Electromagnetic Motors Compare?

You know brushless DC motors, stepper motors, and piezoelectric motors. They use magnets or strain. They rely on electromagnetism and the Lorentz force. Electrostatic motors use the electrostatic force instead.

Here is a simple table.

| Feature | Electrostatic Motor | Electromagnetic Motor |

|---|---|---|

| Main field | Electric field | Magnetic field |

| Drive | High voltage, low current | Low voltage, higher current |

| Core parts | Electrodes, dielectric gap | Windings, iron cores, magnets |

| Best scale | Micro to small | Small to large |

| EMI | Very low | Higher |

| Vacuum use | Strong | Needs care |

| Torque density | Low at macro | High at macro |

In magnetic designs you care about steel. You care about the shape and stack of laminations. If you work with BLDC or induction motors you know that the quality of the stator core lamination and the rotor core lamination matters a lot. Good electrical steel laminations lower loss and raise efficiency. You can learn more about the material and shapes at this resource on electrical steel laminations. If you want a quick primer on how a stator and rotor pair up take a look at this clear guide to stator and rotor basics.

In electrostatic designs you care about permittivity, dielectric strength, insulation, and breakdown voltage. You also care about scaling laws. Forces scale with area and field. Gaps and breakdown limit the field. That is why tiny motors can do well yet big ones struggle.

How Do We Stay Safe With High Voltage?

High field strength needs care. Air has a dielectric strength that limits safe electric field values. Sharp edges can raise the field and trigger spark discharge. Humid air lowers breakdown. Dust and oil can track and arc.

Use smooth shapes. Use clean solid dielectrics, insulating oils, or vacuum. Mind your creepage and clearance distances. Test with pulsed electric fields first at low duty cycles. Protect with resistors and bleeders. Work with one hand when you probe. Respect kV gear. I do. You should too.

Can You Build a Simple Electrostatic Motor?

You can build a safe demo at very low power. Old books show electret motors, Kelvin water dropper toys, and Van de Graaff generator tricks. These show how charges move. They show how electric fields make motion. Keep it low energy. Keep it behind shields. Do not try high voltage work if you lack training.

A neat demo uses a comb drive in a MEMS kit. You move a tiny beam with voltage. You feel the variable capacitance effect in your hands. You can also try a basic DC electrostatic motor with foil strips and a balloon rubbed plastic. It is crude yet fun.

What Do Control Systems and Power Electronics Do?

The drive must switch high voltage fast. You can use power electronics with solid‑state switches. You can shape waveforms for low noise and smooth vibration. High frequency helps make small motors move with high speed.

You also need control systems. A synchronous design needs the rotor to track the field. A stepper design needs the right commutation pattern and steps. A field‑controlled motor can vary torque by changing potential difference. Closed loop control uses sensors. Open loop control uses timing and load models.

What Does the Future Look Like?

I see three tracks. First is micro. Miniaturization keeps going. MEMS electrostatic actuators fit phones, labs, and micro robots. Second is special settings. Aerospace and space exploration need low EMI and vacuum performance. Third is new ways to fly and move air. Ionic wind propulsion and plasma motors use electric fields to push ions. You may see HALE platforms glide with a faint blue glow and almost no noise.

Will we drive cars with electrostatic traction motors soon. Not likely. Torque density at scale is the wall. That said we may see hybrid parts. We may see electrostatic clutches and tiny electrostatically actuated devices in electric vehicles. We may see non‑contact power transmission across small gaps. The future of electrostatic motors is bright in the niches that fit.

I also look back. Andrew Gordon showed the first “electric whirl” in the 1700s. That was an electrostatic generator era. Then Faraday showed electromagnetic rotation in 1821. Today both paths matter. We pick the right tool for the job.

Problem: you may need a motor right now for a new build. You may need reliable supply and strong cores. You may not be ready to jump to electrostatic parts.

Agitate: delay kills projects. Poor cores waste power. EMI can still bite you if the stack hums.

Solution: use proven steel cores while you explore new tech. If you work with BLDC or stepper designs I suggest sourcing quality laminations. Vendors who focus on core shape and loss can lift your power density and efficiency today.

Bonus: Core Concepts You Will See in Practice

- Electric field strength sets force. Field comes from voltage across a gap.

- Capacitance change with angle creates torque in many designs.

- Permittivity and dielectric constant of the gap matter a lot.

- Gaseous, liquid, and solid dielectrics each bring trade‑offs.

- Scaling laws favor tiny gaps and small devices for best torque density.

- Low current cuts heat. High voltage raises field.

- EMI is low since magnets are absent. That helps in MRI or sensor labs.

- Radiation hardening is doable with the right polymers, ceramics, and layout.

A Quick Comparison Table With Extra Details

| Topic | Electrostatic | Electromagnetic |

|---|---|---|

| Force law | F = qE, Coulomb’s Law | Lorentz force |

| Key parts | Electrodes, dielectric medium | Coils, magnets, iron core |

| Control | Voltage driven, commutation of electrodes | Current driven, commutation of windings |

| Typical voltage | kV range | V to hundreds of V |

| Typical current | pA to µA | mA to A |

| Noise/vibration | Very low possible | Depends on design |

| Environment | Great in vacuum, hot or cold with right materials | Needs cooling, lube, and vent plans |

| Related tech | Electrophoretic motors, ionic wind, plasma motors | Brushless DC, stepper, piezoelectric motors |

References

- NASA Glenn Research Center. Ion Propulsion and Electric Propulsion Overviews.

- MIT research articles on ionic wind propulsion and electrohydrodynamic thrust.

- Textbook: Electromechanical Energy Conversion basics from standard EE curricula.

- University MEMS course notes on electrostatic comb drives and actuators.

- Historical notes on Andrew Gordon’s electrostatic “whirl” and early generators.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Do electrostatic motors work without magnets

A: Yes. They use the electric field not the magnetic field. That is why EMI stays low.

Q: Why do they need high voltage

A: High voltage creates a strong field across a small gap. The field stores energy. The energy turns into force.

Q: Are they safe to build at home

A: Only at very low energy and with care. High voltage can hurt. Start with simple demos and shields.

Q: Where do they beat magnetic motors

A: At tiny size, in vacuum, near MRI gear, and where low EMI and low vibration matter most.

Q: Can they power a car

A: Not now. Torque density is too low at large scale. Research continues.

Key Takeaways

- Electrostatic motors turn electric fields into torque with variable capacitance, charge induction, or dielectric polarization.

- They need high voltage and very good insulation, so mind dielectric strength and breakdown voltage.

- They shine in MEMS, vacuum, aerospace, medical devices, and precision motion control where noise and vibration must stay low.

- They differ from electromagnetic motors that rely on magnetic flux and coils. Choose by use case and scaling laws.

- If you need classic motors today your stator and rotor cores matter. See stator core lamination, rotor core lamination, and broader electrical steel laminations to boost quality. For a clear refresher on parts see stator and rotor basics.