How Does Eddy Current Work? A Comprehensive Guide to Its Principles & Applications

As an engineer or designer, you’re constantly dealing with the forces that drive our world, both seen and unseen. You meticulously calculate stresses, analyze thermal loads, and optimize for efficiency. But what about the invisible forces at play within your materials? If you’ve ever wondered how a roller coaster brakes smoothly without touching the track, how an induction cooktop heats a pan without a flame, or how an aircraft wing is inspected for microscopic cracks, you’ve stumbled upon the powerful and ubiquitous phenomenon of eddy currents.

Understanding how eddy currents work isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s a critical piece of knowledge for anyone involved in designing, manufacturing, or maintaining high-performance equipment. It’s the key to unlocking higher efficiency, ensuring safety, and making more informed material and process decisions. This guide is for you—the engineer, the designer, the problem-solver. We’ll break down the physics, explore the applications, and empower you to leverage this fundamental principle in your work.

What We’ll Cover

- The Fundamental Principle: Electromagnetic Induction: A look at the core physics of Faraday’s and Lenz’s laws that make it all possible.

- How Eddy Currents are Generated in a Conductor: A step-by-step explanation of how these electrical “whirlpools” are born.

- Detecting and Interpreting the Unseen: How we can “listen” to the signals from eddy currents to learn about a material’s condition.

- Real-World Applications: Where Eddy Currents Make an Impact: From non-destructive testing to high-speed trains, we’ll explore where this technology shines.

- The Engineering Trade-Offs: Advantages and Limitations: A balanced look at the pros and cons of using eddy current technology.

- Your Engineering Takeaway: A summary of actionable insights to guide your design and decision-making process.

The Fundamental Principle: Electromagnetic Induction

At the very heart of eddy currents lies one of the pillars of physics: electromagnetic induction. This isn’t some obscure concept; it’s the same principle that allows generators to create electricity and transformers to step voltage up or down. To truly grasp how eddy currents work, we first need to understand the two key laws that govern this interaction, discovered by scientific pioneers Michael Faraday and Heinrich Lenz.

Faraday’s Law of Induction: The Spark of Creation

In the 1830s, Michael Faraday made a groundbreaking discovery: a changing magnetic field can create an electric current in a nearby conductor. This is the essence of his Law of Induction.

Think of it this way: imagine you have a simple loop of copper wire connected to a voltmeter. If you just hold a bar magnet stationary inside the loop, nothing happens. But the moment you start moving the magnet—either pushing it in or pulling it out—the voltmeter needle jumps. You’ve just induced an electromotive force (EMF), or voltage, which drives a current through the wire. The key isn’t the magnetic field itself, but the change in the magnetic field passing through the loop (what physicists call magnetic flux). The faster the change, the stronger the induced current.

Lenz’s Law: The Law of Opposition

Faraday told us that a current is induced, but Heinrich Lenz later figured out which way it flows. Lenz’s Law is beautifully simple and profound: the induced electric current will flow in a direction that creates its own magnetic field to oppose the very change that produced it.

It’s like nature’s brake pedal or a law of electrical inertia. If you push the north pole of a magnet toward a coil, the induced current will create its own north pole to push back against you. If you pull it away, the current will reverse to create a south pole to try and pull it back. This opposition is not a minor detail—it is the entire basis for how we detect, measure, and utilize eddy currents for everything from finding flaws to braking a train.

How Eddy Currents are Generated in a Conductor

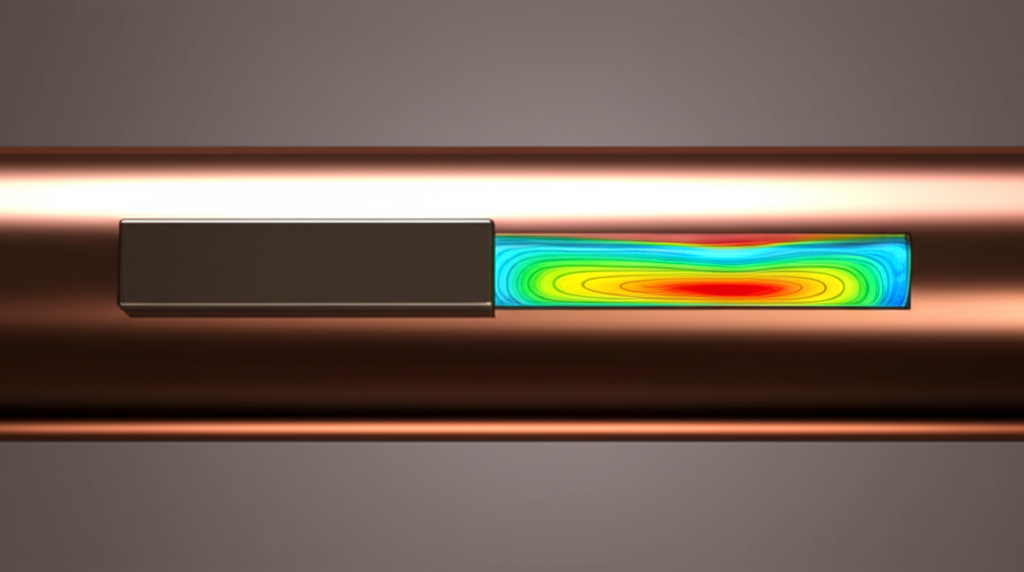

Now that we have the fundamental physics down, let’s apply it to a solid piece of metal. Unlike a simple wire, a block of aluminum or steel is a bulk conductor. When you bring a changing magnetic field near it, you don’t just induce a single current path. Instead, you create countless localized, circular paths of current within the material itself.

These swirling, circular flows of electrons are eddy currents, also known as Foucault currents after their discoverer.

Here’s the step-by-step process:

1. The Dynamic Duo: Alternating Current (AC) and Coils

To create the necessary changing magnetic field, we typically use a probe containing a coil of wire and pass an alternating current (AC) through it. Because the AC is constantly and rapidly switching direction, it generates a primary magnetic field that is also constantly fluctuating—expanding, collapsing, and reversing polarity thousands of times per second. This AC coil is the engine that drives the entire process.

2. The Conductor’s Response: Birth of the “Whirlpools”

When this fluctuating primary magnetic field penetrates the surface of a nearby conductive material (like a sheet of titanium or a copper pipe), it works its magic according to Faraday’s Law. It induces voltages within the material, which in turn drive the flow of eddy currents.

Think of the primary magnetic field as a large paddle stirring a calm river (the conductor’s free electrons). The stirring motion creates small, circular whirlpools—the eddy currents—that swirl just below the surface. These currents aren’t just random; they flow in closed loops in planes perpendicular to the magnetic field. The way these currents are managed is critical in electrical devices, often requiring specialized electrical steel laminations to minimize their energy-wasting effects.

3. Key Factors That Dictate Eddy Current Behavior

The size, strength, and depth of these eddy currents aren’t constant. They are highly dependent on a few key properties of the material and the test setup, which is what makes them so useful for inspection and measurement.

- Material Conductivity: This is a measure of how easily a material allows electricity to flow. A highly conductive material like copper or aluminum will support strong, large eddy currents. A less conductive material like stainless steel will have weaker ones. This is why eddy currents can be used to sort different metals.

- Magnetic Permeability: This describes how easily a material can be magnetized or support a magnetic field. Ferromagnetic materials like iron and steel have high permeability, which strongly concentrates the magnetic field and has a dramatic effect on the test coil. Non-ferromagnetic materials like aluminum or titanium have very low permeability.

- Test Frequency: The frequency of the AC in the probe coil is a crucial variable.

- High Frequency: Creates strong eddy currents that are concentrated very near the surface. This is excellent for detecting tiny surface-breaking cracks.

- Low Frequency: Generates weaker eddy currents that penetrate deeper into the material, allowing for the detection of subsurface flaws.

- This phenomenon is known as the skin effect, and managing this trade-off between sensitivity and depth of penetration is key to successful testing.

- Coil-to-Material Distance (Lift-off): The strength of the magnetic field drops off rapidly with distance. Even a tiny gap between the probe and the test surface (known as lift-off) can significantly weaken the eddy current response. While often a nuisance, this effect can also be harnessed to measure the thickness of non-conductive coatings, like paint on metal.

Detecting and Interpreting the Unseen

So, we’ve created these invisible whirlpools of current inside a material. But how do we use them to find a crack or measure conductivity? The answer lies back with Lenz’s Law—the law of opposition.

The Secondary Magnetic Field: The Echo in the System

The eddy currents swirling inside the material are, themselves, a moving electric charge. And as we know, any moving charge creates its own magnetic field. According to Lenz’s Law, this secondary magnetic field generated by the eddy currents directly opposes the primary magnetic field from the coil.

This interaction is a delicate dance. The primary field induces the eddy currents, and the eddy currents create a secondary field that pushes back on the primary field. It’s this “push back” that we can measure.

The Language of Impedance: How We Read the Signals

The primary coil in our probe has a property called impedance, which is essentially its total opposition to the flow of alternating current. When the coil is in the air, its impedance has a certain value. But when you bring it near a conductor, the opposing secondary magnetic field from the eddy currents affects the primary coil, causing its impedance to change.

Here’s the brilliant part: anything that disrupts the flow of the eddy currents will change their secondary magnetic field, which in turn causes a measurable change in the probe coil’s impedance.

- A crack or flaw acts like a dam in the river, forcing the eddy current “whirlpools” to divert around it. This makes them smaller and weaker.

- A change in conductivity (e.g., due to heat treatment) changes how easily the currents can flow.

- A change in thickness can limit how large the current loops can become.

Each of these disruptions creates a unique signature—a change in both the magnitude and phase angle of the coil’s impedance.

From Signal to Solution: Instrumentation and Analysis

Modern eddy current instruments are incredibly sophisticated. They precisely drive the coil with a stable AC frequency and then measure these minute changes in its impedance. These changes are often displayed on an impedance plane graph, where different signals correspond to different conditions like lift-off, cracks, or material variations.

A skilled NDT technician learns to interpret these signals, much like a doctor reads an EKG. They use reference standards with known defects to calibrate the instrument and then analyze the signals from the test part to identify and characterize any hidden flaws.

Real-World Applications: Where Eddy Currents Make an Impact

The principles of eddy currents are not confined to the lab. They are the backbone of critical technologies across dozens of industries, ensuring safety, improving quality, and enabling new innovations.

Non-Destructive Testing (NDT): The Industrial Workhorse

This is arguably the most significant application of eddy current principles. Eddy Current Testing (ECT) is a powerful method for inspecting conductive materials without damaging them.

- Flaw and Crack Detection: In the aerospace industry, ECT is a frontline defense against metal fatigue. According to NDT standards, it can reliably detect fatigue cracks as small as 0.25 mm (0.01 inches) in critical aluminum aircraft components like wing skins and fastener holes, preventing catastrophic failures.

- Heat Exchanger Tube Inspection: Over 70% of the tubes in power plants and petrochemical refineries are inspected using eddy current methods. It’s fast, requires no messy couplant, and can quickly identify issues like pitting, corrosion, and stress corrosion cracking in critical components like heat exchangers and the transformer lamination core. Specialized techniques like Remote Field Eddy Current (RFEC) are used for ferromagnetic materials like carbon steel.

- Material Sorting: In high-volume manufacturing, eddy current sorting systems can verify material properties on the fly, processing up to 1000 parts per minute. This ensures, for example, that an automotive assembly line doesn’t accidentally use an incorrect aluminum alloy or an improperly heat-treated steel component.

- Corrosion Under Insulation (CUI): A specialized technique called Pulsed Eddy Current (PEC) can detect wall thinning and corrosion through thick layers of insulation and weather jackets. A case study from the oil and gas industry showed that using PEC saved a plant $100,000 to $500,000 per inspection cycle by avoiding the costly and time-consuming process of stripping insulation. This same push for efficiency through advanced physics drives innovation in the design of modern motor core laminations to reduce energy losses.

Eddy Current Braking Systems: Stopping Without Touching

Remember Lenz’s Law? The opposing magnetic field creates a drag force. Eddy current brakes harness this force to provide incredibly smooth, silent, and wear-free braking. A powerful electromagnet is positioned next to a rotating metal disc (like a train wheel or a conductive rail). When the magnet is energized, it induces massive eddy currents in the moving disc. These currents create a powerful opposing magnetic field that exerts a strong retarding force, converting the vehicle’s kinetic energy into heat in the disc.

German ICE high-speed trains use these brakes to generate up to 5 kN of braking force per module, operating effectively at speeds over 300 km/h (186 mph) without any friction or mechanical wear. You’ll also find them on roller coasters for a smooth stop and in industrial machinery and exercise equipment.

Induction Heating: Cooking and Forging with Magnetism

Eddy currents aren’t just for inspection and braking; they can also generate immense heat. When eddy currents flow through a material with electrical resistance (which all materials have), they dissipate energy as heat (a phenomenon called joule heating).

In an induction furnace, a large coil carrying a high-frequency AC surrounds a metal crucible. This induces massive eddy currents within the metal, causing it to heat up and melt—without any external flame. An induction cooktop works the same way, inducing eddy currents directly in the bottom of your steel or cast-iron pan. This method is incredibly efficient; up to 90% of the energy is transferred directly to the pan, compared to just 40-55% for a gas range.

Metal Detectors: Finding Treasure and Ensuring Safety

A hobbyist’s metal detector and an airport security scanner both operate on eddy current principles. The detector’s search head contains a coil that transmits a changing magnetic field into the ground or toward a person. If a conductive object (like a coin, weapon, or piece of foil) passes through this field, eddy currents are induced within it. These currents generate their own weak, opposing magnetic field, which is then picked up by a second receiver coil in the detector head. Modern security scanners are sensitive enough to reliably detect metal objects as small as 0.5 grams.

The Engineering Trade-Offs: Advantages and Limitations

Like any technology, eddy current methods have distinct strengths and weaknesses. Understanding these is crucial for selecting the right tool for the job.

The Strengths of Eddy Current Technology

- High Sensitivity: It is extremely sensitive to surface and near-surface cracks and flaws.

- Non-Contact: The probe does not need to touch the part, and no liquid couplant is required (unlike ultrasonic testing).

- Fast and Portable: Inspections can be performed very quickly, and the equipment is often lightweight and battery-powered.

- Versatile: It can be used not only for flaw detection but also for measuring material properties, sorting alloys, and gauging coating thickness.

- Unaffected by Surface Conditions: Can inspect through thin layers of paint, dirt, or coatings that would interfere with other methods.

The Boundaries of the Technology

- Conductive Materials Only: It cannot be used on non-conductors like plastics, ceramics, or composites.

- Limited Penetration Depth: The skin effect restricts its use to surface and near-surface inspection. It’s not suitable for finding deep internal flaws in thick components.

- Sensitive to Geometry: Complex shapes, sharp edges, and variations in the part’s geometry can create confusing signals that are difficult to interpret.

- Requires Skilled Operators: Interpreting the impedance plane signals requires significant training and experience to differentiate between flaws and non-relevant indications.

- Calibration is Key: The instrument must be carefully calibrated on reference standards that are acoustically and geometrically similar to the part being tested.

Your Engineering Takeaway

Eddy currents are a powerful manifestation of fundamental electromagnetic laws. By understanding how they are generated and how they interact with materials, we can harness them for a vast array of practical applications that make our world safer, more efficient, and more advanced.

Here are the crucial points to remember:

- The Foundation: Eddy currents are born from Faraday’s and Lenz’s Laws—a changing magnetic field induces a current in a conductor that creates its own field to oppose the change.

- The Mechanism: An AC-driven coil creates a primary magnetic field, which induces swirling eddy currents in a test material. These currents produce an opposing secondary magnetic field.

- The Signal: Any discontinuity in the material—a crack, corrosion, or change in alloy—disrupts the eddy currents. This disruption is detected as a change in the probe coil’s electrical impedance.

- The Variables: The outcome is controlled by four key factors: the material’s conductivity and permeability, the test frequency, and the distance between the probe and the part (lift-off).

- The Applications: This principle is the engine behind non-destructive testing, frictionless braking systems, efficient induction heating, and sensitive metal detectors.

Grasping these principles empowers you to ask the right questions, engage in more effective conversations with NDT specialists, and appreciate the complex physics at play in both industrial processes and everyday technology. For a deeper dive into how these very principles are meticulously controlled to maximize performance in electric motors, exploring the design and material science behind stator core lamination can provide invaluable insights into the practical application of electromagnetic theory. As technology continues to advance with innovations like array probes and AI-driven signal analysis, the reach and power of eddy current technology are only set to grow.