How Long Do Motor Mounts Last? Lifespan, Factors & Replacement Guide

Table of contents

- Introduction: Why Motor Mounts Matter More Than You Think

- Average Motor Mount Lifespan: The Number Everyone Asks Me For

- What Really Affects Motor Mount Life

- Driving conditions and habits

- Environment and fluid leaks

- Mount type and material quality

- Vehicle specifics

- Signs of Bad Motor Mounts: Symptoms You Shouldn’t Ignore

- What Happens If You Don’t Replace Bad Mounts

- Inspection and Maintenance: How I Keep Mounts Alive Longer

- When To Replace Motor Mounts: Practical Rules I Use

- DIY Motor Mount Inspection: A Simple Step‑by‑Step

- Cost, Time, and Warranty: What I Tell Friends Before They Book a Shop

- FAQs I Hear All The Time

- Final Thoughts: Prioritize Motor Mount Health

Introduction: Why Motor Mounts Matter More Than You Think

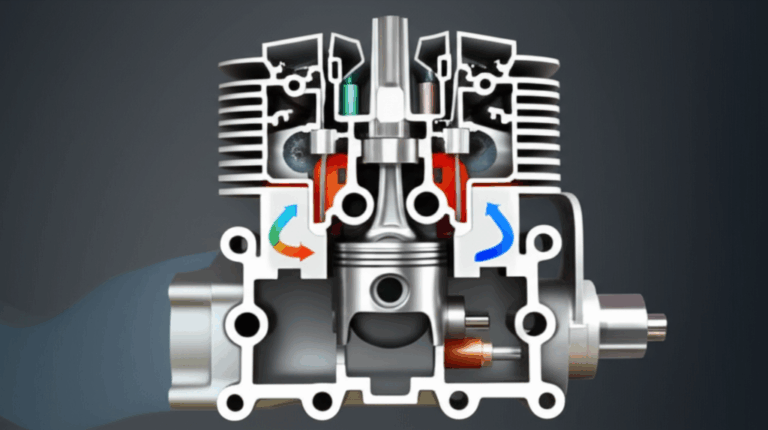

If you’ve ever felt your steering wheel shake at idle or heard a thud when you shift into drive you’ve met a motor mount problem in the wild. I’ve dealt with motor mounts on my own cars and in countless driveway diagnostics for friends. These unassuming chunks of rubber or fluid-filled housings do two big jobs. They secure the engine and transmission to the chassis. They isolate vibration so your teeth don’t chatter on the way to work.

When mounts fail you feel it. The whole car starts to buzz. Shifts get harsh. The engine can rock enough to smack nearby parts. I learned the hard way on my old daily after an oil leak soaked a hydraulic mount. The car went from smooth to shaker table in a week. I replaced the mount and the difference felt like night and day.

Let’s tackle the question that brings most people here. How long do motor mounts last and what can you do about it.

Average Motor Mount Lifespan: The Number Everyone Asks Me For

Here’s the straight answer I give customers and friends.

- Typical lifespan: 5 to 7 years or about 50,000 to 100,000 miles

- Outliers: Some mounts make it past 150,000 miles. I’ve also seen mounts fail before 30,000 miles when abused or soaked in oil

- Transmission mounts often follow a similar timeline but they can last a little longer on gentle highway commuters

That range frustrates people. I get it. Still different materials age differently and driving conditions vary wildly. Mileage is only part of the story. Heat cycles and exposure matter. So does torque. The more the engine twists the more the mounts flex and wear.

What Really Affects Motor Mount Life

I always break this down into four buckets. How you drive. Where you drive. What your mounts are made of. What you drive.

Driving conditions and habits

- Aggressive acceleration and braking: Hard launches twist the powertrain and hammer the mounts. If you love stomping the gas you cut motor mount lifespan by 20 to 50 percent in my experience

- Stop‑and‑go traffic: Constant starts and shifts stress mounts more than steady highway cruising

- Rough roads and off‑road use: Potholes and washboards add vertical shocks and side loads that tear rubber and fatigue metal brackets

- Towing and heavy loads: Torque goes up. Flex goes up. Wear goes up

- Manual transmissions and harsh shifting: Sudden clutch engagement or sloppy mount alignment makes clunking and shortens life

Environment and fluid leaks

- Extreme heat: Hot climates and under‑hood heat bake rubber. Rubber hardens then cracks. Hydraulic mounts also age faster when the internal fluid breaks down

- Extreme cold: Cold makes rubber stiffer. Stiff rubber cracks more easily during big torque events

- Oil and fluid leaks: Engine oil and transmission fluid soften rubber compounds. They swell then split. I’ve seen oil contamination cut mount life by 30 to 70 percent

- Road salt and chemicals: Corrosion attacks metal shells and brackets. Once rust gets under a bonded rubber layer the mount can separate

- Exhaust heat soak: A mount that sits near the exhaust or turbo downpipe sees extra heat. Expect faster degradation without proper heat shielding

Mount type and material quality

You’ll find three common types plus a modern twist.

- Rubber mounts: The classic choice. They offer great vibration isolation and a comfortable ride. They can crack and sag over 5 to 8 years as rubber naturally hardens and checks

- Hydraulic or fluid‑filled mounts: These add liquid chambers for better dampening at idle and low rpm. They feel smoother. They can leak once the internal bladder or seal fails which usually happens after 75,000 miles or so

- Polyurethane mounts: Stiffer and more durable than rubber. Better for performance and torque control. They transmit more vibration into the cabin and can squeak over time. Many last longer than rubber yet you trade comfort for durability

- Active mounts: Some vehicles use electronically controlled or vacuum‑modulated mounts to counter specific vibration frequencies. They ride beautifully. They bring more parts that can fail like internal valves or control systems

Quality matters too.

- OEM vs aftermarket: OEM motor mount life expectancy tends to be more consistent for noise vibration and harshness control. Aftermarket motor mount durability ranges from excellent to awful. Cheap mounts often fail early. I avoid no‑name bargain mounts because they cost more in the long run

- Performance mounts: Performance motor mounts with solid or very stiff construction control engine movement better. They can shorten the life of adjacent parts and your patience due to added vibration

Vehicle specifics

- Engine size and torque: Bigger torque means bigger twist. Turbo engines and diesels can be harder on mounts

- Vehicle weight and subframe design: A heavy vehicle with a soft subframe makes mounts work harder

- Drivetrain layout: Transverse engines use front and rear torque mounts that take a beating during acceleration and braking. Longitudinal setups can load side mounts more when the engine rolls

- Age and mileage: Old rubber degrades even on low‑mileage garage queens. Time matters as much as miles

I also remind EV owners that motor mounts still matter. Electric motors make instant torque which can rock the powertrain. Engineers tune mounts to manage those loads while keeping vibration low. If you’re curious about how an electric motor’s rotating parts interact you can read more about the stator and rotor. That background helped me explain to an EV owner why a worn front mount still caused clunks on throttle even though the motor itself had no idle vibration.

Signs of Bad Motor Mounts: Symptoms You Shouldn’t Ignore

I use a simple mental checklist. You can do the same. If two or more of these show up I inspect the mounts right away.

- Excessive vibration: Steering wheel shakes. Floorboard buzzes. Seats hum. It’s most obvious at idle or when you slip into gear and hold the brake

- Clunking or thudding: You hear a thud during gear changes or when you blip the throttle. Parking lot three point turns become noisy

- Visible engine movement: Watch the engine while a helper blips the throttle in park. If it rocks more than an inch or lifts on one side a mount is probably blown

- Rough shifting or jerking: The drivetrain feels unstable. You feel a knock on and off throttle. Automatics can slam into gear more harshly

- Fluid leaks at the mount: Hydraulic mounts leave a wet stain. Sometimes you’ll see dark fluid on the mount body or crossmember

- Visual degradation: Cracked rubber. Torn or separated rubber from the metal shell. Sagging that lets metal touch metal. That last one makes nasty vibration and can be dangerous

I had a customer with a small crossover that idled fine in neutral but shook in drive. We found the right hydraulic mount leaking and the rubber had collapsed. The replacement fixed the steering wheel shake and the clunk on reverse.

What Happens If You Don’t Replace Bad Mounts

People ask is it safe to drive with bad motor mounts. My short answer is sometimes yet not for long. Here’s why I advise quick action.

- Accelerated wear on other parts: CV joints, driveshafts, and exhaust flex pipes all see more movement and stress

- Possible damage to engine or transmission cases: Excess roll can let metal brackets hammer nearby parts

- Safety risks: Severe failures can let the engine shift enough to affect steering precision or jam a component under extreme conditions

- Rough driving experience: The car feels older than it is which hurts value and makes every trip annoying

A friend waited months after the first clunk. By then the bad front torque mount destroyed the rear mount too. He paid twice for labor. Replace early and you avoid the domino effect.

Inspection and Maintenance: How I Keep Mounts Alive Longer

You can’t prevent all wear yet you can stack the deck in your favor.

- Inspect regularly: I peek at mounts every oil change or at least every 15,000 to 30,000 miles. Look for cracks, sagging, or fluid stains

- Fix leaks fast: Oil contamination kills rubber. If you see a valve cover or rear main seeping deal with it before it soaks the mount

- Drive smoothly: Ease into the throttle. Avoid neutral drops and clutch dumps. Your wallet will thank you

- Use heat shields where needed: If a mount sits near the exhaust make sure shields are present and intact

- Choose quality parts: Go OEM or a reputable aftermarket brand that matches your vehicle’s NVH targets

- Plan by age: At 5 to 8 years I watch mounts closely even on low‑mileage cars because rubber degrades with time

I also like to think about how vibration works at its source. Engines produce torque pulses. Mounts act like tuned filters. If you want a deeper dive into why torque twists the powertrain the basics of the motor principle help. That understanding makes it clear why mounts need specific stiffness and damping to cancel problem frequencies.

When To Replace Motor Mounts: Practical Rules I Use

You won’t find a universal motor mount replacement interval. Mounts don’t wear out on a schedule like oil filters. I replace mounts when:

- Symptoms appear: Vibration, clunks, excess movement, or fluid leaks

- Visual checks show damage: Cracks, tears, collapsed rubber, or separated bonding

- A related repair makes access easy: If the subframe is out for a different repair I replace obviously tired mounts while I’m in there

- Age and environment justify it: Over 8 years in hot climates often means hard brittle rubber even if miles are low

Should you replace all mounts at once. Not always. If one mount fails early due to oil contamination you replace that one and fix the leak. If the car has 120,000 miles and two mounts are failing I often replace the set for balanced performance. Balanced mounts reduce the chance that a fresh stiff mount transfers new stress into an old soft mount.

I also consider transmission mounts. If engine mounts are failing the transmission mount likely isn’t far behind. A wobbly transmission mount can mimic engine mount symptoms with clunks on shifts and extra vibration under load.

DIY Motor Mount Inspection: A Simple Step‑by‑Step

If you’re handy you can spot trouble without fancy tools. Use common sense and follow safety steps. If anything feels risky stop and let a pro handle it.

1) Park on level ground. Set the parking brake. Use wheel chocks

2) Open the hood. With the engine idling watch for movement. Have a helper shift from park to drive to reverse while holding the brake. Small twitch is normal. Big lurch points to a failed mount

3) Shut the engine off. Use a bright light. Inspect each mount

- Look for cracks, splits, or rubber separating from metal

- On hydraulic mounts look for wetness or fluid stains

- Check for sagging or metal‑to‑metal contact

4) Use a pry bar gently: With the engine supported by its own weight apply light leverage near the mount to see if the rubber deforms too easily. Don’t go wild. You’re checking for obvious slop not bending brackets

5) Inspect nearby parts: Exhaust flex joint, half shafts, and the radiator fan shroud for signs of contact or stress

6) Road test: Listen for thuds during takeoff, braking, and shifting. Pay attention to vibrations at idle vs under load

If you’re unsure take photos and get a professional opinion. A mechanic can load the engine safely and pinpoint which mount failed.

Cost, Time, and Warranty: What I Tell Friends Before They Book a Shop

Costs vary by vehicle and mount design. I break it down like this so no one is surprised.

- Parts cost per mount: About 50 to 250 dollars for most rubber or hydraulic mounts. Performance or specialty mounts can cost more

- Labor per mount: About 1 to 4 hours depending on access. Some mounts take 30 minutes. Others require lifting the engine and dropping a subframe

- Total per mount: About 200 to 1,000 dollars all in. Replacing multiple mounts in one visit often saves labor

- Warranty: Many quality mounts carry a 12‑month warranty. Some OEM parts go longer. Keep the receipt and make sure the shop’s labor policy matches the parts warranty

Pro tip. If you already need major work that involves subframe removal coordinate mount replacement then. You save time and usually money.

FAQs I Hear All The Time

How often should I replace motor mounts

- Based on symptoms not mileage. Inspect every 15,000 to 30,000 miles or every 1 to 2 years and replace when you see signs of failure

Can motor mounts last 200k miles

- Yes in gentle highway use with no leaks and good heat management I’ve seen mounts go that far. It’s not common. Expect 50,000 to 100,000 miles as the realistic range

Are cheap motor mounts worth it

- Usually not. Cheap mounts often use poor rubber or weak bonding. They can fail early or transmit more vibration than OEM. I stick with reputable brands or OEM

Is it safe to drive with bad mounts

- Sometimes for a short period if symptoms are mild. I don’t push it. Bad mounts can damage other parts and safety can suffer if the engine moves too much

Do I replace all mounts at once

- It depends. Replace the failed mount right away. If the car has high mileage and the others look tired replacing the set can restore smoothness and prevent repeat labor

What causes premature motor mount failure

- Oil leaks, aggressive driving, extreme heat, poor quality parts, and rough roads lead the list. Fluid‑filled mount leaks and rubber cracking are the most common failure types

How do rubber, hydraulic, and polyurethane mounts compare

- Rubber mounts isolate vibration best for daily driving. Hydraulic mounts isolate idle vibrations even better but can leak with age. Polyurethane mounts last longer in performance use and control torque well yet they transmit more vibration into the cabin

Do transmission mounts last longer than engine mounts

- Sometimes. They often see less heat and oil exposure which helps them live longer. Still a rough engine mount can beat up the transmission mount

What about diesel motor mounts

- Diesels make strong low‑rpm torque. That added twist can shorten mount life. Many diesels use heavy‑duty or hydraulic mounts to control vibration

Are active motor mounts more reliable

- They ride beautifully. Reliability depends on the control system and the quality of the mount. When they fail the symptoms mirror hydraulic mounts plus you might see fault codes in advanced systems

How much play should a motor mount have

- Very little. You should not see more than about half an inch of controlled movement during a simple throttle blip test. Large rocking or a visible lift on one side suggests a failed mount

Can a mechanic tell if my mounts are bad quickly

- Yes. A good mechanic can combine visual inspection with a controlled engine load test and spot a bad mount fast

Do aftermarket performance mounts shorten other component life

- They can. Stiffer mounts shift more vibration into the chassis. That can rattle interior parts and add wear to nearby bushings. It’s a tradeoff between control and comfort

Is there a motor mount life expectancy calculator

- I haven’t found one that predicts reliably because driving style and environment vary. Use inspections and symptoms to guide you

What does a good motor mount look like

- Rubber should be intact with no cracks or separations. The mount should sit level with no sagging. Hydraulic mounts should be dry with no signs of fluid

Deeper Notes on Vibration and Materials

I’ll keep this practical yet if you like the why behind the what this part helps. Engines and motors both create vibration at certain frequencies. Mounts work like filters tuned to block those frequencies. Engineers choose rubber compounds, hydraulic chambers, and void patterns to target frequencies at idle and under load.

Electric vehicles bring their own twist. Electric motors run smoother at low rpm yet they produce strong instantaneous torque. That torque still loads the mounts and subframe. The structure of the motor can influence vibration patterns too. Laminated cores in electric motors help manage magnetic losses and reduce certain vibration tones. If you want to see how those cores come together you can skim this primer on motor core laminations or the material science behind electrical steel laminations. I’ve used that knowledge to explain why some EVs feel glassy smooth while others hum a little at specific speeds. The mounts and the motor both play a part.

Real‑World Examples From My Notebook

- The oil‑soaked mount: A small sedan came in with rough idle vibes and a thud engaging drive. Valve cover leak dripped on the right hydraulic mount for months. The rubber swelled then split and the mount leaked. We fixed the leak and replaced the mount. The vibration disappeared

- The performance tradeoff: A friend installed polyurethane side mounts on a turbo hatch to control wheel hop. It worked and the shifter felt tighter. The cabin buzzed more at idle and low speed. He was fine with the trade

- The high‑mileage highway car: A commuter with 170,000 miles still had original rubber mounts. Highway miles and clean engine bay saved them. We replaced them proactively during a timing job because access was easy and the rubber showed early cracks

Quick Reference: What To Expect In Numbers

I’m not a fan of hard numbers for soft parts yet here’s a practical baseline I’ve seen hold up.

- Average lifespan: 5 to 7 years or 50,000 to 100,000 miles. Some go 150,000 plus. Some fail at 30,000 when abused

- Aggressive driving impact: 20 to 50 percent shorter life

- Oil and fluid leaks impact: 30 to 70 percent shorter life depending on severity

- Hydraulic mount leak likelihood: Goes up after about 75,000 miles

- Rubber aging: Cracking and hardening often show up after 5 to 8 years even with low miles

- Recommended inspection: Every 1 to 2 years or every 15,000 to 30,000 miles

Treat these as guardrails not gospel. Your climate, driving style, and vehicle design move the needle.

How I Choose Replacement Mounts

I keep it simple.

- Daily driver: OEM or OEM‑quality rubber or hydraulic mounts for best comfort

- Performance street: A mix works well. Polyurethane torque mount with quality rubber side mounts often balances control and comfort

- Track or drag: Stiffer mounts or solid mounts can make sense. Not for street comfort or long component life

I avoid no‑name bargain brands. I check warranty terms and I read reviews for premature tearing or leaking. I also match the mount type to the car. If the factory used a hydraulic mount I don’t downgrade to solid rubber unless I accept the extra vibration.

A Note on EVs and Hybrids

EVs use mounts too. They handle torque reactions just like gas cars. Hybrids add start‑stop events and engine kicks that can stress mounts differently. If you own a hybrid and notice a clunk when the engine starts or stops check the torque mount first. Understanding motor structure helps frame those NVH conversations as well which is why I sometimes point curious owners to foundational reads like stator and rotor for context.

Step‑By‑Step Replacement Overview

I won’t turn this into a full DIY because procedures vary by car yet here’s the typical flow so you know what your mechanic is doing.

- Support the engine or transmission with a jack and a wood block or an engine support bar

- Remove components that block access like intake ducts or brackets

- Unbolt the old mount from the engine side and the chassis side

- Compare new and old for height and orientation

- Install the new mount loosely. Lower or shift the engine slightly to relieve bind

- Torque bolts to spec with the vehicle at normal ride height when possible to prevent preloading the rubber

- Reinstall related parts. Road test for vibration and clunks

Shops that specialize in your make move quickly because they know the access tricks. That’s why labor time ranges so much from one car to another.

Final Thoughts: Prioritize Motor Mount Health

If you skimmed to the end here’s the meat. Most motor mounts last 5 to 7 years or about 50,000 to 100,000 miles. Driving style, heat, and leaks can cut that short. Watch for vibration at idle, clunks on shifts, and visible engine movement. Fix leaks fast. Inspect mounts every 15,000 to 30,000 miles or every year or two. Replace based on symptoms not mileage alone. Choose quality parts that match your goals for comfort or performance.

I learned to treat motor mounts as guardians of everything else bolted to the powertrain. Keep them healthy and your car feels tight, safe, and quiet. Ignore them and little problems turn into big bills. If you crave a deeper understanding of torque and vibration you can always explore the fundamentals of the motor principle and the materials behind motor core laminations. It’s nerdy yet it makes you appreciate the humble mount that keeps all that force in check.