How Strong Is a 3.6 HP 2‑Cycle Boat Motor? Performance, Capabilities, and Real‑World Lessons

Table of Contents

- What I Learned About 3.6 HP in the Real World

- What Does 3.6 HP Really Mean for Boat Propulsion?

- Horsepower vs. Thrust: Why “HP” Alone Can Mislead

- The 2‑Cycle Personality: Light, Simple, Punchy

- Typical Static Thrust Output in Pounds

- Ideal Boat Types for a 3.6 HP Outboard

- Best Suited Uses

- When It’s Not Enough

- Shaft Length, Transom Height, and Mounting Details That Matter

- Speed Expectations: How Fast Can You Go With 3.6 HP?

- What Controls Speed on Small Boats

- Typical Speeds for Dinghies, Jon Boats, and Canoes

- Displacement Hull Speed Limits Explained

- Performance in Varied Water Conditions

- Currents and Wind

- Waves and Rough Water

- Shallow Water, Skinny Creeks, and Weed Beds

- Trolling and Slow‑Speed Control

- 3.6 HP 2‑Cycle vs. Common Alternatives

- Versus a 5 HP Outboard

- Versus an Electric Trolling Motor

- Key Advantages and Disadvantages of 3.6 HP 2‑Cycle Outboards

- Essential Considerations Before You Buy

- Getting the Most From a 3.6 HP Motor

- Prop Size and Pitch

- Setup and Trim

- Fuel Mix, Maintenance, and Storage

- Troubleshooting the Usual Gremlins

- Real‑World Scenarios: What I’ve Seen Actually Work

- Quick Answers to Popular Questions

- Final Verdict: Is a 3.6 HP 2‑Cycle Strong Enough for You?

What I Learned About 3.6 HP in the Real World

I have run small outboards on everything from tiny inflatables to tin jon boats to modest sailboat tenders. A 3.6 HP 2‑cycle motor lands in a sweet spot when you value portability and simplicity. It starts easy. It travels well. It sips fuel at a modest pace. Yet it has hard limits that you feel the moment the wind pipes up or the boat gets heavy.

When I first tried a 3.5–3.6 HP two‑stroke on an 8‑foot inflatable, I expected fireworks. I got steady push and a smile instead. In flat water that setup moved 4–6 MPH with one adult. It felt calm and predictable. Swap to a 12‑foot jon boat with two people and a cooler. Now you watch the bow push water instead of climbing on top of it. The speed drops a notch. The motor still works for fishing or as a tender, yet it stops being your “cover ground fast” option.

So how strong is a 3.6 HP outboard? Strong enough to move small craft with confidence in calm water. Not strong enough to force heavy loads or fight strong current on command. Let me break down the details so you can match expectations to your boat and your water.

What Does 3.6 HP Really Mean for Boat Propulsion?

Horsepower vs. Thrust: Why “HP” Alone Can Mislead

Horsepower measures how fast an engine can do work. It does not tell you how much “push” you’ll feel at the transom. Propeller choice, gear ratio, RPM, and hull type turn horsepower into motion. That is why trolling motors quote thrust in pounds while gas outboards quote horsepower. People feel thrust when they launch or fight a headwind. They notice horsepower as speed once the boat moves cleanly.

You will often see questions about “horsepower to thrust conversion” for marine use. No single formula converts HP to pounds of thrust with accuracy. Prop efficiency changes the picture. Shaft losses matter. Hull drag matters too. Treat any neat conversion chart as a rough guess. The water does not care about neat guesses. It responds to the full system.

If you want to understand how electric motors generate torque and deliver it to a prop, this quick primer on the stator and rotor helps. It does not convert HP to thrust. It does show where that torque comes from in electric systems.

The 2‑Cycle Personality: Light, Simple, Punchy

A 3.6 HP 2‑stroke typically weighs 35–50 lb. That puts it in grab‑and‑go territory. Two‑strokes breathe every revolution, so they tend to feel eager at low RPM. You mix fuel and oil. You accept more noise and smoke than a four‑stroke. In return you get a compact, easy‑to‑service package that loves light boats and simple days on the water.

Typical Static Thrust Output in Pounds

Static thrust for a 3.6 HP outboard usually lands around 30–50 lb. That range depends on the propeller and RPM. On the water that means solid bite at idle and in no‑wake zones. You get smooth docking. You get predictable low‑speed control. You do not get bulldozer push against big current or gusty headwinds with a heavy hull.

Ideal Boat Types for a 3.6 HP Outboard

Best Suited Uses

From my trips and test days, these setups pair well with 3.6 HP:

- Small inflatable dinghies and tenders up to 8–10 feet

- Lightweight jon boats in the 10–12 foot range with one adult or a light load

- Canoes and small rowboats with proper motor mounts

- Auxiliary power for small sailboats up to roughly 20 feet for harbor maneuvering

- Fishing and slow trolling on calm lakes and ponds

- Tender runs from a mooring to the ramp or dock

Keep boat weight light. Think dry weights up to about 250–450 lb before people and gear. The motor shines when the boat sits high and clean. It starts to struggle when the transom settles deep and the bow throws a wall of water.

When It’s Not Enough

I tried to cheat physics a few times. It never paid off.

- Planing larger boats or hefty loads does not happen. You might “semi‑plane” a tiny hard dinghy in perfect conditions with a very light driver. Do not build your plan around that.

- Boats over 12–14 feet or hulls that weigh much over ~400–500 lb dry feel sluggish and sticky.

- Strong river currents or stiff tidal flows can overpower a 3.6 HP setup. Expect slow or negative progress once current creeps past 2–3 MPH with a moderate load.

Shaft Length, Transom Height, and Mounting Details That Matter

Get shaft length right. Most small dinghies and jon boats need a short shaft. Many small sailboat auxiliaries need a long shaft. Mount so the anti‑cavitation plate rides level with or slightly below the hull bottom. Aim for clean water at the prop. Trim so the prop shaft runs parallel to the water at cruising speed.

- Short shaft vs long shaft matters more than people realize

- Transom height and tilt holes affect cavitation and ventilation

- Keep weight centered and low to help small boats track straight

Speed Expectations: How Fast Can You Go With 3.6 HP?

What Controls Speed on Small Boats

Speed depends on four things.

- Hull type: displacement vs planing

- Hull length and waterline

- Weight and trim

- Conditions: wind, waves, and current

Propeller pitch and diameter matter too. So does gear ratio and engine RPM. On small boats, hull type rules the roost. You can throw more power at a displacement hull and still hit a wall. Which leads to…

Typical Speeds for Dinghies, Jon Boats, and Canoes

My numbers match what most owners report:

- 8–10 foot inflatable dinghy with one person: 4–6 MPH (3–5 knots)

- 10–12 foot jon boat with one person: 5–7 MPH (4–6 knots)

- Canoe or light rowboat with careful weight trim: 4–6 MPH

Two people or gear can drop those numbers by 1–2 MPH. Chop and headwind can shave off more. You feel the difference fast. The motor still moves you. It just does not hurry.

Displacement Hull Speed Limits Explained

Most small dinghies and jon boats in this class operate in displacement mode with 3.6 HP. The classic rule of thumb for displacement hulls says top speed in knots equals 1.34 times the square root of waterline length in feet. An 8‑foot waterline gives a hull speed near 3.8 knots. A 12‑foot waterline gives roughly 4.6 knots. You can exceed that a bit on light planing hulls. You will not blast past it without enough power to climb out and plane.

Performance in Varied Water Conditions

Currents and Wind

I watch current and wind first when I run small motors. Light to moderate current near 2 MPH is workable with a light boat. Once current reaches 3 MPH with a load on board, you may squeak by or stall. It depends on hull shape and prop bite. A steady 10–15 knot headwind can feel like driving uphill. Your speed drops. Your fuel burn climbs. Your patience gets a workout.

Think of it like pushing a shopping cart on a level floor vs a carpeted ramp. The cart feels light on tile. It drags and slows on carpet. Water does the same thing to small boats.

Waves and Rough Water

Short, steep chop steals speed. The prop sucks air when the stern lifts. You hear RPM spike. You lose bite. In real chop I throttle back and accept a slower ride. The motor lasts longer. My back thanks me later.

Shallow Water, Skinny Creeks, and Weed Beds

A 3.6 HP outboard often includes a shallow‑water drive or tilt pin that lets the prop skim. Use it with care. Sand and weeds do not show mercy. Keep a spare shear pin if your model uses one. Carry a paddle or a push pole. I treat shallow exploration like I borrowed the skeg from a friend. I go slow. I get home without drama.

Trolling and Slow‑Speed Control

For fishing, a 3.6 HP can troll cleanly at low RPM. It holds a steady crawl without surging. It sips fuel at idle and low throttle. I prefer it over a big outboard idling all day. It does not match the whisper of an electric motor. It does well for lakes where combustion engines are allowed.

3.6 HP 2‑Cycle vs. Common Alternatives

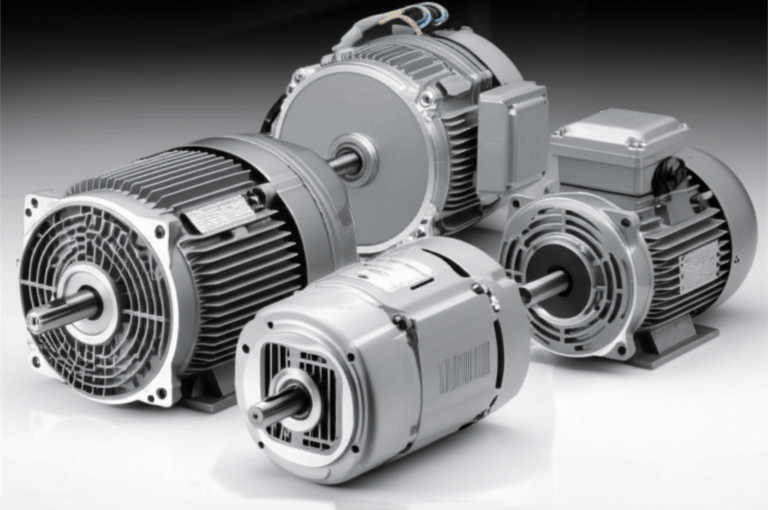

Versus a 5 HP Outboard

The jump from 3.6 HP to 5 HP looks small on paper. It does not feel small on the water. That extra power can push a wider range of 10–12 foot boats and can plane a very light hull with a light driver. You get more headroom for current and wind. You pay with more weight and often more cost. If you want to carry a second person often or haul gear, 5 HP starts to look smart.

Versus an Electric Trolling Motor

People ask if a 55‑lb thrust trolling motor equals a certain HP. You can rough it in and say a 55‑lb motor is somewhere near one horsepower at the prop. Real use tells a better story. Electric motors deliver smooth low‑end torque. They shine for stealth and precise control. They lose ground on top speed and range once you compare to a 3.6 HP gas outboard with a few gallons of fuel. Batteries add weight. They take time to recharge. Gas refuels fast and runs for hours.

If you want to peek inside how electric motors create torque, start with the basics of stator and rotor. Curious about the guts of many modern trolling motors? They rely on brushless designs that use a laminated steel stator for efficiency. This explainer on a BLDC stator core shows how those laminations shape torque and cut losses. The same lamination concept also shows up in motor alternators and transformers to reduce eddy currents. If you want the materials angle, these are called electrical steel laminations. This design detail sits behind the quiet efficiency many anglers love.

For gas outboards, the “motor principle” differs since combustion creates the torque inside a cylinder. If you like fundamentals, this high‑level overview of motor principle will help you connect how torque and RPM translate to useful work in any motor system.

Bottom line in use:

- Electric wins for stealth, instant torque at low speed, and zero local emissions at the point of use

- Gas wins for range, higher top speed on lightweight hulls, and quick refueling

Key Advantages and Disadvantages of 3.6 HP 2‑Cycle Outboards

Pros

- Lightweight and portable for easy carry and mounting

- Simple design with fewer parts than many 4‑strokes

- Good low‑RPM torque for docking and trolling

- Affordable compared to bigger motors

- Easy to service for DIY owners

Cons

- Louder than 4‑strokes and electric options

- Higher exhaust emissions than modern 4‑strokes

- Requires fuel‑oil mixing and careful ratios

- Limited top speed and load handling

- Less fuel efficient at high RPM than a comparable 4‑stroke

Essential Considerations Before You Buy

I run through this checklist with friends who ask for advice.

- Your boat’s size and weight: Aim for dry weights up to ~250–450 lb for best results

- Your passengers and gear: Frequent two‑person trips push the limits fast

- Primary use: Main propulsion, auxiliary for a sailboat, or trolling duty

- Water conditions: Calm lakes reward small motors; strong rivers punish them

- Local rules: Some lakes restrict 2‑stroke engines due to emissions

- Shaft length: Match short vs long shaft to transom height

- Prop size and pitch: Make sure stock prop fits your use; low pitch helps push

- Fuel tank style: Internal tanks are simple; external tanks extend range

- Motor weight: Can you lift it safely on and off the boat?

- Warranty and parts: Easy access to service and spares matters

- Used motor condition: Compression, spark, cooling water stream, and gear oil all tell a story

Getting the Most From a 3.6 HP Motor

Prop Size and Pitch

Small changes in propeller pitch can help a 3.6 HP motor perform better with your hull. A lower pitch prop boosts acceleration and push at lower speeds. It trades off some top‑end speed. That trade helps heavy dinghies and jon boats that live in displacement mode. A higher pitch prop can squeeze a hair more top speed on a very light boat. I start with the stock prop. I only change if I see the engine over‑rev or bog.

What to watch:

- Engine RPM at wide‑open throttle with normal load

- Launch bite and ability to hold speed in light chop

- Signs of cavitation or ventilation when trimmed wrong

Setup and Trim

I see more performance lost to setup than to horsepower. Keep the anti‑cavitation plate near the hull bottom. Square the motor on the transom so the prop sees clean water. Test tilt holes. Trim in for load and chop. Trim out a notch for top speed on a light day if the prop still holds. Balance the boat so it sits level. Move gear forward if the stern squats and drags a big wake.

Fuel Mix, Maintenance, and Storage

Fuel mix ratio matters. Follow your manual’s recommended oil‑to‑gas ratio. Most small 2‑strokes call for something like 50:1. Use fresh fuel. Use a quality 2‑stroke oil. Add fuel stabilizer if the gas will sit more than a few weeks.

Basic maintenance keeps these little engines happy:

- Spark plug: Inspect, clean, and replace as needed

- Gear oil change: Replace at least yearly; look for milkiness or metal

- Cooling system: Confirm a strong tell‑tale stream; clear any salt buildup

- Carburetor: Keep fuel clean; drain bowls for storage to prevent varnish

- Winterizing: Fog the engine, drain or stabilize fuel, and store dry

I pull the prop once a season. I grease the shaft. I check for fishing line behind the hub. I learned that lesson the hard way. Fishing line can chew a seal. Water sneaks into the gearcase. Repairs get expensive.

Troubleshooting the Usual Gremlins

Small 2‑strokes act up for simple reasons. I start with the basics.

- Hard start or no start: Check fuel flow, primer bulb, and spark plug

- Poor idle: Clean idle jet, adjust air screw, and inspect spark plug

- Overheating: Check water intake for blockage and impeller condition

- Slipping or revving without push: Look for ventilation, prop damage, or wrong engine height

- Vibration: Inspect prop for dings and balance; verify motor is tight on the transom

Noise and vibration are part of the deal with small two‑strokes. Rubber mounts help. Good ear protection helps too. I often wear slim earplugs on long runs.

Real‑World Scenarios: What I’ve Seen Actually Work

Here are a few setups I have either run myself or helped tune for friends.

- 9‑foot inflatable tender, one adult, light gear:

- 3.6 HP 2‑stroke with short shaft

- 4–6 MPH in flat water

- Great for mooring to dock runs and quick fishing trips

- Two adults drop speed closer to 3–4 MPH

- 12‑foot jon boat, one adult and modest tackle:

- 3.6 HP 2‑stroke

- 5–7 MPH on calm water with the right trim

- Stable trolling all day at low RPM

- Two adults plus cooler push it toward 4–5 MPH

- 10‑foot hard dinghy used as a sailboat tender:

- 3.6 HP 2‑stroke long shaft when used on a higher transom

- Reliable docking and marina maneuvering in light wind

- Punches into light chop fine; heavy winds slow the dance

- Small river with 2–3 MPH current:

- 3.6 HP outboard can maintain headway upstream with a light hull and one person

- Add a second person or strong gusts and progress fades

- I plan turns with current in mind; I avoid pinching myself against bridge pilings or tight bends

- Shallow lake with weed beds:

- Outboard runs fine at modest speed in open pockets

- I tilt up a notch and idle through thin patches

- Prop guards help at the cost of efficiency; I usually skip them and choose smarter routes

Quick Answers to Popular Questions

How fast is a 3.6 HP boat motor?

- Expect 4–7 MPH depending on hull, load, and conditions. Most setups sit in the 4–6 MPH band.

What can a 3.6 HP motor push?

- Light inflatables, small dinghies, canoes, and lightly loaded 10–12 foot jon boats. It works as auxiliary power on small sailboats for harbor work.

How much thrust does 3.6 HP produce?

- Roughly 30–50 lb of static thrust depending on prop and RPM.

Can a 3.6 HP 2‑stroke plane a boat?

- Not typically. It might flirt with a partial plane on a tiny, very light hull with an equally light driver. Treat planing as a bonus, not a promise.

What fuel consumption should I expect?

- Around 0.3–0.5 gallons per hour at a steady cruise. Throttle position and load swing the number.

How far can I go?

- With a 3‑gallon external tank at a sensible cruise, many owners see 6–10 hours of run time. Your hull and throttle hand set the true range.

Is a 2‑stroke too loud or smoky?

- It is louder than a 4‑stroke and any electric motor. Modern 2‑stroke oils help reduce smoke. Good tune helps too.

What about environmental rules?

- Some lakes or regions limit carbureted 2‑strokes due to emissions. Check local regulations before you buy.

What shaft should I pick?

- Short shaft for most dinghies and jon boats. Long shaft for many sailboat mount heights. Match the anti‑cavitation plate to the hull bottom at install.

What prop should I use?

- Start with the stock prop. If you carry more load and need more push, consider a lower pitch prop. Watch your wide‑open RPM and choose accordingly.

Final Verdict: Is a 3.6 HP 2‑Cycle Strong Enough for You?

I use a 3.6 HP 2‑stroke when I want simplicity and quiet days on small water. It shines on 8–10 foot inflatables and light 10–12 foot jon boats with one person. It excels as auxiliary power for small sailboats and as a dinghy motor for tender chores. It trolls beautifully. It carts around without grunts and groans.

It is not the pick for planing larger craft, hauling heavy friends and gear, or beating strong currents on big rivers. You can ask it to do those jobs. It will try. Physics will shrug.

Here is my rule of thumb. If your boat is small and light and your water is calm most days, a 3.6 HP 2‑cycle gives you honest push, easy ownership, and lots of smiles per gallon. If you want margin for wind, passengers, and current, bump up to a 5 HP. You will not regret the extra headroom.

Take the time to match shaft length to your transom. Keep the prop modest in pitch for better push. Mix your fuel right. Change your gear oil. Winterize if you store the motor in a cold garage. Treat it well. It will pay you back with years of steady service.