How to Calculate Induction Motor Efficiency: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Formulas, and Standards

Of course. Here is the comprehensive, long-form article based on your instructions.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Why I Became Obsessed with Induction Motor Efficiency

- The Fundamental Concepts You Absolutely Need to Know

- Input Power (P_in): The Juice You’re Paying For

- Output Power (P_out): The Real Work Getting Done

- The Golden Formula of Efficiency

- Understanding Motor Losses: The Energy Thief

- A Deep Dive into Induction Motor Losses

- Electrical Losses (Copper Losses)

- Magnetic Losses (Core Losses)

- Mechanical Losses (Friction and Windage)

- Stray Load Losses: The Mysterious Culprit

- The Two Main Methods for Calculating Motor Efficiency

- Method 1: The Direct Method (Input-Output)

- Method 2: The Indirect Method (Loss Segregation)

- Real-World Factors That Wreck Motor Efficiency

- Decoding Efficiency Standards: What IE and NEMA Mean

- My Go-To Toolkit for Measuring Efficiency

- Conclusion: It’s More Than Just a Number

Introduction: Why I Became Obsessed with Induction Motor Efficiency

I still remember the day it clicked for me. I was a junior engineer on the floor of a massive manufacturing plant, surrounded by the hum of dozens of induction motors. My manager pointed to a huge 100 HP motor driving a pump and said, “That thing costs us over $50,000 a year in electricity.” I was stunned. He then asked a simple question that changed my perspective forever: “But how much of that money is actually doing work, and how much are we just turning into heat?”

That’s the essence of motor efficiency. It’s the difference between productive work and wasted energy. In my experience, understanding how to calculate it is one of the most powerful skills you can have in an industrial setting. It’s not just an academic exercise; it’s a direct path to saving money, improving reliability, and reducing your carbon footprint.

Electric motors are the workhorses of our world, consuming nearly half of all global electricity. Calculating their efficiency isn’t just about finding a percentage. It’s about performing an energy audit on your most critical equipment. In this guide, I’m going to walk you through everything I’ve learned over the years—from the basic formulas to the hands-on testing methods—so you can do the same.

The Fundamental Concepts You Absolutely Need to Know

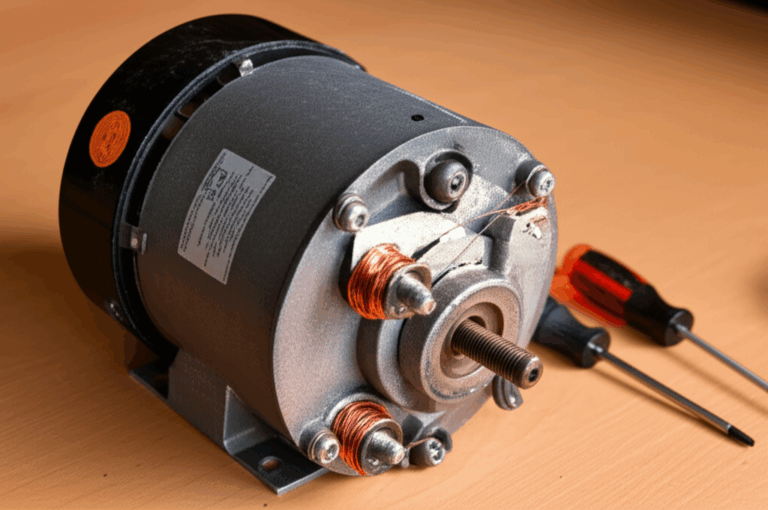

Before we start plugging numbers into formulas, you need to get a solid grasp of a few core ideas. Trust me, getting these right makes everything else fall into place. An induction motor is a wonderfully simple machine in principle. It has two main parts: the stationary part, or the stator, and the rotating part, the rotor. The complex dance between the magnetic fields of the stator and rotor is what creates motion. But how efficiently does it happen?

Input Power (P_in): The Juice You’re Paying For

Input power is the electrical energy you feed the motor from the grid. Think of it as the total amount of “fuel” the motor consumes. We measure this in watts (W) or kilowatts (kW). To find it, you can’t just measure the current and voltage and multiply them together. You also need to account for the power factor, which is a measure of how effectively the current is being converted into useful work.

So, for a three-phase motor, the formula is:

P_in = √3 V I * PF

Where:

-

Vis the line-to-line Voltage. -

Iis the line Current. -

PFis the Power Factor.

You’ll need a good power analyzer or wattmeter to get an accurate reading of this. It’s the baseline for everything. It’s the number on your utility bill.

Output Power (P_out): The Real Work Getting Done

Output power is the useful mechanical work the motor delivers at its shaft. This is what actually drives your pump, fan, or conveyor belt. It’s what you’re really paying for. We measure this in watts or horsepower (HP).

Calculating it involves two key measurements:

P_out = Torque * Speed

Where:

-

Torque (τ)is the rotational force, typically measured in Newton-meters (N-m) or pound-feet (lb-ft). -

Speed (ω)is the rotational speed, measured in radians per second or revolutions per minute (RPM).

Getting this number is often the tricky part, as it usually requires a device called a dynamometer to directly measure the torque and speed under load.

The Golden Formula of Efficiency

Now for the simple part. Efficiency, represented by the Greek letter eta (η), is just the ratio of the useful output power to the total input power. It tells you what percentage of the electrical energy is being successfully converted into mechanical work.

η (%) = (Output Power / Input Power) * 100

If a motor has an efficiency of 95%, it means that for every 100 watts of electricity you put in, you get 95 watts of useful mechanical work out. The other 5 watts? They’re lost.

Understanding Motor Losses: The Energy Thief

Those “lost” 5 watts are what we call total losses. They don’t just disappear; they are converted primarily into heat. This is the crucial concept:

Input Power = Output Power + Total Losses

Calculating efficiency is really a game of accurately accounting for these losses. The lower the losses, the higher the efficiency. Simple as that. The heat generated by these losses is also what limits a motor’s performance and shortens its lifespan.

A Deep Dive into Induction Motor Losses

To really master efficiency calculation, you have to become a detective of energy loss. These losses come from different sources within the motor, and understanding them is key, especially for the indirect calculation method.

Electrical Losses (Copper Losses)

These are also known as I²R losses, and they happen because the copper windings in the stator and rotor have electrical resistance. Just like the element in a toaster, when current flows through the windings, they heat up. This heat is wasted energy.

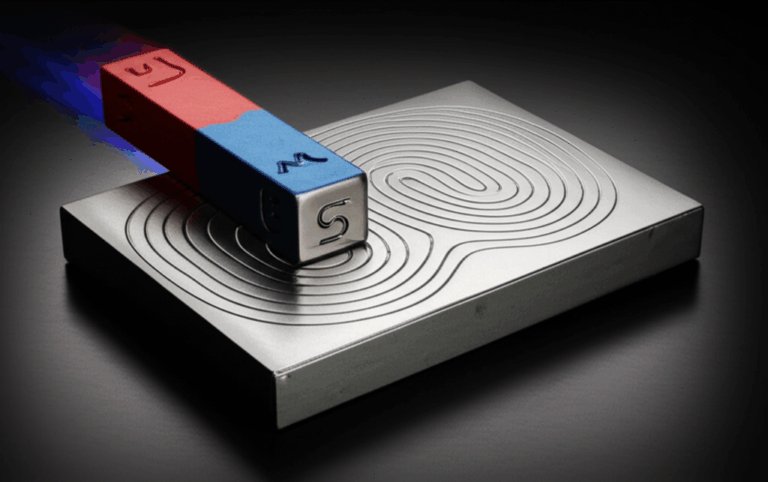

Is) and the stator resistance (Rs). The formula is Psc = 3 I_s² R_s for a three-phase motor.Prc = Slip * Air Gap Power. The quality of the rotor core lamination plays a role here by ensuring the magnetic field is channeled effectively, which indirectly influences the currents and subsequent losses.Magnetic Losses (Core Losses)

These losses occur in the motor’s steel core, which is made of a stack of thin plates. As the magnetic field rapidly alternates, it causes two types of losses in this core material:

Core losses are heavily dependent on the motor’s design and the voltage applied. They are relatively constant as long as the voltage and frequency don’t change.

Mechanical Losses (Friction and Windage)

These are the physical losses that have nothing to do with electricity or magnetism.

Stray Load Losses: The Mysterious Culprit

This is the catch-all category for all the other little losses that are incredibly difficult to measure or predict. They arise from things like non-uniform magnetic fields and complex current patterns under load. For a long time, engineers just approximated them as a small percentage of the output power. Now, standards like IEEE 112 provide methods to estimate them more accurately based on testing.

The Two Main Methods for Calculating Motor Efficiency

Okay, now that you know what you’re measuring, how do you actually do it? There are two main approaches I use, and the right one depends on your situation, your equipment, and the accuracy you need.

Method 1: The Direct Method (Input-Output)

This is the most straightforward and intuitive way to think about efficiency. You simply measure the electrical power going in and the mechanical power coming out at the same time and then divide them.

When I Use It: I use this method when I have the motor on a test bench, I can easily connect to the shaft, and I have a dynamometer. It’s great for verifying a manufacturer’s claims or comparing two motors under identical load conditions.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

P_in), the torque (τ), and the speed (RPM).Pout) from your torque and speed measurements. Then, use the golden formula: η = (Pout / P_in) * 100.Advantages:

- It’s conceptually simple.

- It measures true, real-world efficiency under a specific load.

Disadvantages:

- Requires expensive and specialized equipment (dynamometers).

- It’s often impractical or impossible to do in the field on an installed motor.

- Small measurement errors in both input and output can lead to a larger error in the final efficiency number.

Method 2: The Indirect Method (Loss Segregation)

This is the detective’s method. Instead of measuring input and output directly, you meticulously measure or calculate each of the individual losses we just discussed (copper, core, mechanical, etc.). Then, you add them all up to find the Total Losses.

From there, you can calculate efficiency for any given load. For a specific Pout, the input power would be Pin = P_out + Total Losses. Then you can find the efficiency. This method is defined by standards like IEEE 112 and IEC 60034-2-1 and is considered more accurate, especially for large motors.

When I Use It: This is my go-to for high-accuracy testing, for very large motors that can’t be easily loaded, or when I don’t have a dynamometer.

The Key Tests Involved:

R_s) at room temperature, which you then correct for the motor’s normal operating temperature.P_no-load.Putting It All Together (The Calculation):

Rs, Pno-load, and P_blocked (which represents full-load copper losses).Total Losses = Pcopper + Pcore + Pfw + Pstray.η = (Poutrated / (Poutrated + Total Losses)) * 100.Advantages:

- Extremely accurate if performed correctly.

- Doesn’t require a full-load dynamometer.

- It allows you to calculate efficiency at any load point, not just the one you tested.

Disadvantages:

- It’s more complex and requires a deeper understanding of motor theory.

- Requires several distinct tests and careful calculations.

Real-World Factors That Wreck Motor Efficiency

Calculating efficiency on a test bench is one thing. Maintaining it in the real world is another. I’ve seen perfectly good motors waste a ton of energy because of these common issues:

- Load Level: Motors are most efficient when running between 75% and 100% of their rated load. I’ve walked into countless facilities where a massive 50 HP motor is driving a load that only needs 15 HP. This is called “over-motoring,” and it’s a huge efficiency killer. The motor’s efficiency drops off a cliff at very light loads.

- Voltage Fluctuations and Imbalance: Motors are designed to run on a stable, balanced three-phase supply. Even a small voltage imbalance between the phases can cause circulating currents, dramatically increasing losses and overheating the motor. This is a very common motor problem that can lead to premature failure.

- Poor Power Quality: Harmonics in your electrical supply, often caused by VFDs or other electronics, can distort the voltage waveform. This “dirty power” creates extra magnetic and electrical losses, causing the motor to run hotter and less efficiently.

- Aging and Maintenance: As motors age, bearings wear out, insulation degrades, and lubrication fails. A poorly done motor rewind can also slash efficiency by 1-3% if the shop uses cheaper materials or changes the winding design.

Decoding Efficiency Standards: What IE and NEMA Mean

When you look at a motor’s nameplate, you’ll often see an efficiency rating like “IE3” or “NEMA Premium.” These aren’t just marketing terms; they are standardized efficiency classes that tell you the quality of the motor.

- IEC Standards (Global): The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) uses the “IE” classification system.

- IE1: Standard Efficiency

- IE2: High Efficiency

- IE3: Premium Efficiency (This is the mandatory minimum in many parts of the world, including the EU and USA, for new motors).

- IE4: Super Premium Efficiency

- NEMA Standards (North America): The National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) uses terms like “Energy Efficient” and “Premium Efficient,” which roughly correspond to IE2 and IE3, respectively.

The key takeaway is this: upgrading from an old IE1 motor to a new IE3 motor can result in a 2-8% efficiency gain. That might not sound like much, but for a motor running 24/7, the cost savings can be thousands of dollars per year, often paying for the new motor in less than two years.

My Go-To Toolkit for Measuring Efficiency

If you’re serious about this, you’ll need a few key pieces of equipment. Here’s what’s in my bag when I’m doing a motor audit:

- Power Analyzer: This is the most important tool. It measures voltage, current, power factor, and true input power all in one.

- Tachometer: A non-contact laser tachometer is perfect for safely measuring the motor’s shaft speed (RPM).

- Clamp-on Ammeter: For quick current readings on each phase to check for load and balance.

- Digital Multimeter with Ohms Function: Essential for the DC winding resistance test. A more advanced tool is a digital low-resistance ohmmeter (DLRO) for higher precision.

- Torque Transducer/Dynamometer: This is the big-ticket item for direct method testing.

Conclusion: It’s More Than Just a Number

Calculating the efficiency of an induction motor might seem like a dry, technical task, but I see it differently. Every percentage point of efficiency you can account for—or improve—represents real savings, greater reliability, and a step towards sustainability.

When you learn to measure and understand these losses, you’re no longer just looking at a humming piece of machinery. You’re reading the story of its performance. You’re seeing the wasted energy that’s costing your company money and contributing to unnecessary carbon emissions. And once you can see it, you can fix it. Whether you’re using the quick-and-dirty direct method or the meticulous indirect method, the goal is the same: to turn that invisible waste into visible savings. And that’s a skill worth mastering.