How to Calculate Motor Torque: Formulas, Examples, and Practical Applications

Table of contents

- Understanding Motor Torque: The Essentials

- Fundamental Formulas for Motor Torque Calculation

- Method 1: Torque from Force and Lever Arm

- Method 2: Torque from Power and Rotational Speed

- Calculating Torque for Specific Motor Types

- DC Motors

- AC Induction Motors

- Synchronous and BLDC Motors

- Servo Motors and Stepper Motors

- Geared Motors

- Practical Considerations That Change Real Torque

- Efficiency and Losses

- Load Type and Motion Profile

- Operating Conditions and Control Methods

- Reading Motor Datasheets

- Continuous vs Stall vs Peak Torque

- Tools and Methods for Measuring Motor Torque

- Common Mistakes and How I Troubleshoot Them

- Real-World Examples and Numbers You Can Use

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts and a Quick Checklist

I did not learn torque from a textbook alone. I learned it on the shop floor with a stopwatch in one hand and a hot motor in the other. Over the years I have sized motors for conveyors, robotics joints, pump skids, and a stubborn turntable that squealed at startup. Every time the same questions come up. How do I calculate motor torque? Which formula fits my case? Where do efficiency, slip, and gear ratios show up? In this guide I will walk you through the exact methods I use. I will share the formulas, the gotchas, and the quick checks that keep me out of trouble.

You will see me use plain units like Newton‑meter (Nm), foot‑pound (ft‑lb), and pound‑force‑inch (lbf‑in). I will talk about RPM, horsepower, watts, and kilowatts. I will show you how torque relates to speed and power. I will also show you how DC motor torque lines up with current and torque constant. If you need a practical way to go from “I know my load and speed” to “I know my required torque” you are in the right place.

Understanding Motor Torque: The Essentials

Torque is rotational force. Think of a wrench on a bolt. You push with a force at a certain distance from the center. That twist is torque. The basic definition looks simple:

- Torque (T) = Force (F) × Radius (r)

Engineers call that product a moment of force. Units matter. In SI units you get Newton‑meters. In Imperial units you get foot‑pounds or pound‑force‑inches.

Standard torque units:

- 1 Nm ≈ 0.73756 ft‑lb

- 1 Nm ≈ 8.8507 lbf‑in

Why do accurate motor torque calculations matter? Because torque sizing drives motor selection. Get it wrong and the system stalls or overheats. Oversize it and you waste money on the motor, the drive, and the energy bill. I see this often. Many industrial motors are oversized by at least a full frame. That hurts efficiency at light loads and drags down power factor. A well chosen motor runs close to its operating sweet spot so it runs cooler and wastes less power.

A few variables show up again and again:

- Force and radius for direct mechanical calculations

- Power and rotational speed for shaft calculations

- Current and torque constant for DC and BLDC motors

- Speed in RPM or rad/s

- Efficiency when you move from electrical input to mechanical output

- Gear ratio and gearbox efficiency when you add a reducer

If you want a refresher on how motors create torque from electromagnetic fields you can skim the basics of the motor principle. I will stay practical here and keep the math as lean as possible.

Fundamental Formulas for Motor Torque Calculation

I keep three torque methods in my toolbox. Force and lever arm. Power and speed. Current and torque constant. Pick the one that matches the data you have.

Method 1: Torque from Force and Lever Arm

The most direct formula comes from physics:

- T = F × r

- Where T is torque, F is tangential force at the radius, r is radius

Example I still use when teaching a new tech:

- You lift a 50 N weight with a 0.1 m radius pulley

- T = 50 N × 0.1 m = 5 Nm

That is the torque required at the shaft to hold the weight right at the threshold of motion. If you want acceleration you will need more. If friction helps or hurts you will need to account for it.

Method 2: Torque from Power and Rotational Speed

This is the most common approach on the job. When I see motor power in kW or HP and I know speed in RPM I go straight to these:

- Metric: T (Nm) = (P (kW) × 9549) / N (RPM)

- Imperial: T (ft‑lb) = (HP × 5252) / N (RPM)

Where do 9549 and 5252 come from? They come from P = T × ω with ω in rad/s and unit conversions to RPM and kW or HP. You do not need to re‑derive this every time. Memorize the constants and move on.

Real systems are not ideal. Efficiency matters. If you only know electrical input power then do this:

- Pout = η × Pin

- Then use P_out in the torque formula

Practical example:

- A 2.2 kW motor nameplate with 90% efficiency at 1450 RPM

- P_out = 0.90 × 2.2 = 1.98 kW

- T = (1.98 × 9549) / 1450 ≈ 13.05 Nm

Imperial example:

- A 5 HP motor at 1750 RPM with 88% efficiency

- P_out = 0.88 × 5 = 4.4 HP

- T = (4.4 × 5252) / 1750 ≈ 13.2 ft‑lb

Do not forget the efficiency adjustment when you estimate shaft torque from electrical power. That mistake trips up many teams.

Tip: I like to convert final torque into lbf‑in for small mechanisms. Multiply ft‑lb by 12 or multiply Nm by 8.8507.

Calculating Torque for Specific Motor Types

Different motor types give you different ways to estimate torque. DC motors give you a neat linear model with current. Induction motors give you a torque‑speed curve with slip. Servos and steppers lean on datasheets. Gears change everything at the output.

DC Motors

For brushed DC and BLDC motors I go to:

- T = Kt × Ia

- Kt is the torque constant in Nm/A or lbf‑in/A

- Ia is the armature current

You will see a back‑EMF constant Ke in V/(rad/s). In SI units Kt equals Ke numerically. That connection comes from Faraday’s Law and Lenz’s Law. It shows how gearheads and motor designers match windings to magnets and speed.

Two real world notes from my bench:

- Winding resistance and voltage set how much current you can pull at a given speed

- As speed rises the back EMF rises which reduces current for a given supply voltage

Worked example:

- A DC motor lists Kt = 0.08 Nm/A

- At 6 A you get T = 0.08 × 6 = 0.48 Nm

- If the motor has a 10:1 gearbox at 85% efficiency the output torque ≈ 0.48 × 10 × 0.85 ≈ 4.08 Nm

That simple line can save you hours during prototyping.

AC Induction Motors

Induction motors do not give a simple current‑to‑torque line. The torque depends on slip. Slip is the difference between synchronous speed and actual shaft speed. You can still estimate rated torque from rated output power and RPM.

- T ≈ (Pout × 9549) / Nshaft

- Where N_shaft is the actual shaft RPM at the operating point

If you do not know shaft RPM then remember synchronous speed Ns = 120 f / p where f is frequency in Hz and p is number of poles. At 60 Hz and 4 poles Ns = 1800 RPM. The motor might run around 1750 RPM at rated load. That difference is slip. The torque‑speed curve has characteristic regions: high starting torque for some designs, a pull‑up region, a breakdown torque peak, then rated torque near nominal speed.

Factors you cannot ignore:

- Supply voltage affects torque production

- Pole count and frequency set synchronous speed

- Stator and rotor currents produce the electromagnetic torque

- Increased slip means more rotor current and more heat

Quick estimate example:

- A 3 kW 4‑pole motor on a 50 Hz system with rated speed 1450 RPM and 92% efficiency

- P_out = 0.92 × 3 = 2.76 kW

- T = (2.76 × 9549) / 1450 ≈ 18.2 Nm

If you need starting torque or breakdown torque check the torque‑speed curve. Do not assume flat torque.

Synchronous and BLDC Motors

Synchronous motors and BLDC motors produce torque using a locked field relationship between stator and rotor. Their torque control can be very linear in field‑oriented control systems. For BLDC you still see T = Kt × I. For PM synchronous you will work with control parameters rather than simple slip.

Torque ripple can creep in with some BLDC and stepper drives. That ripple shows up as vibration at low speed. In many projects I reduce ripple by adjusting PWM frequency, tuning the controller, or picking a motor with better magnet and lamination design.

Servo Motors and Stepper Motors

For servo motors and stepper motors I treat the datasheet as gospel. You will see:

- Continuous torque

- Peak torque

- Holding torque for steppers

- Rated speed and torque curves

- Thermal limits and duty cycle

With servos the drive limits current which limits torque. With steppers the holding torque at standstill looks impressive yet torque falls with speed. Microstepping makes motion smoother yet it does not raise maximum torque. I check the torque‑speed curve and I add a safety factor when inertia mismatch is large.

Geared Motors

Gears change torque and speed. The math is straightforward:

- Tout = Tin × Gear Ratio × η_gearbox

- Nout = Nin / Gear Ratio

I add gearbox efficiency η_gearbox every time. Planetary gearboxes might hit 90% to 95% per stage. Worm gear drives can sit much lower. Grease, temperature, and duty cycle change that number in practice.

A quick conveyor example will show how this plays out in the real world later. For now remember that gear ratios boost torque while they also reduce speed.

Practical Considerations That Change Real Torque

Torque lives in the messy world. Losses, load types, and environment shift your numbers. Control methods shape torque delivery. I learned to respect these factors after cooking more than one motor during a long ramp test.

Efficiency and Losses

You can write down four big buckets:

- Copper losses in windings (I²R)

- Core losses in iron (hysteresis and eddy currents)

- Mechanical losses (friction and windage)

- Stray load losses

Core losses depend on lamination material and thickness. Better laminations mean lower eddy currents and lower heat which boosts efficiency. The quality of the stator core lamination and the design of the rotor core lamination influence torque density and torque ripple. Material choice matters too. High‑grade electrical steel laminations cut core losses which keeps motors cooler under load.

Typical efficiencies I see in the field:

- Small motors under 1 HP often 60% to 80%

- Standard AC induction 1 to 100 HP often 85% to 92%

- Premium efficiency motors (IE3 or NEMA Premium) around 90% to 96%

- Brushed DC motors about 65% to 80%

- BLDC motors often 85% to 95%

Do not guess. Look at the datasheet and nameplate and test your actual system.

Load Type and Motion Profile

Load torque depends on the application. I sort loads into three groups:

- Constant torque: conveyors and positive displacement pumps

- Torque proportional to speed: viscous fan loads and agitators

- Torque proportional to acceleration: inertia dominated moves in robotics and indexing tables

Acceleration torque can fool you. You must add Taccel = Jtotal × α where J_total is the reflected moment of inertia at the motor shaft and α is angular acceleration. Gearboxes reflect inertia by the square of the ratio. Inertia matching between motor and load makes servo systems happier.

Do not forget friction and gravity. Friction adds constant drag. Gravity adds or subtracts torque depending on orientation. I always draw a free‑body diagram even if it is on a napkin.

Operating Conditions and Control Methods

Temperature, supply voltage, and control strategy will change delivered torque.

- Low voltage reduces torque in AC and DC drives

- High ambient temperature reduces continuous ratings due to thermal limits

- VFD control unlocks more flexibility for AC motors with proper tuning

- Soft starters limit inrush but they do not grant continuous speed control

- PWM current control in BLDC and servo systems shapes torque response

- Power factor and harmonics matter on the electrical side yet they do not change shaft torque directly

Reading Motor Datasheets

I read datasheets like a pilot reads a checklist. Slowly and with respect. I look for:

- Rated power and rated speed

- Rated torque if provided

- Efficiency and power factor at load points

- Torque‑speed curves

- Thermal class and duty cycle

- Continuous vs peak current for servos and BLDC

- Stall torque for DC motors and steppers

I also factor in mechanical details. Shaft size. Bearings. Cooling method. Protection class. The torque you can safely make is always bound by thermal and mechanical limits.

Continuous vs Stall vs Peak Torque

These terms confuse teams during reviews so I spell them out.

- Stall torque: maximum torque at zero speed for a DC motor supplied at a given voltage. You cannot hold it for long without overheating

- Continuous torque: torque the motor can deliver indefinitely without exceeding temperature rise

- Peak torque: higher short‑term torque allowed by the drive and motor for a brief period

I design with continuous torque for steady operation then I check that peak torque covers acceleration and disturbances with margin.

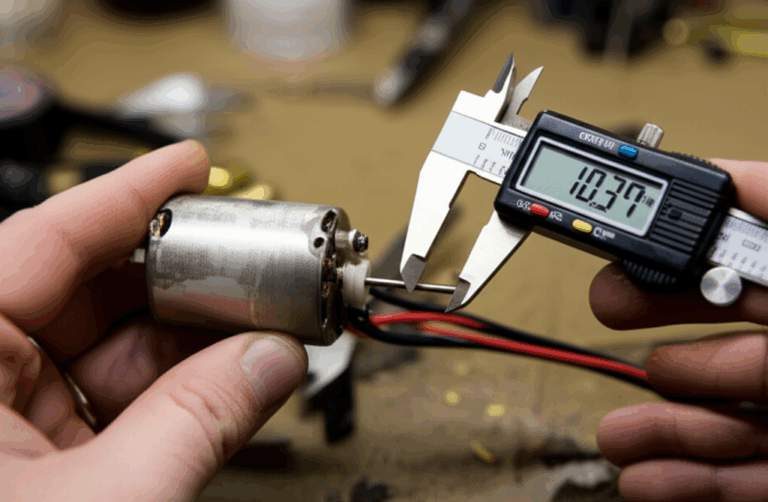

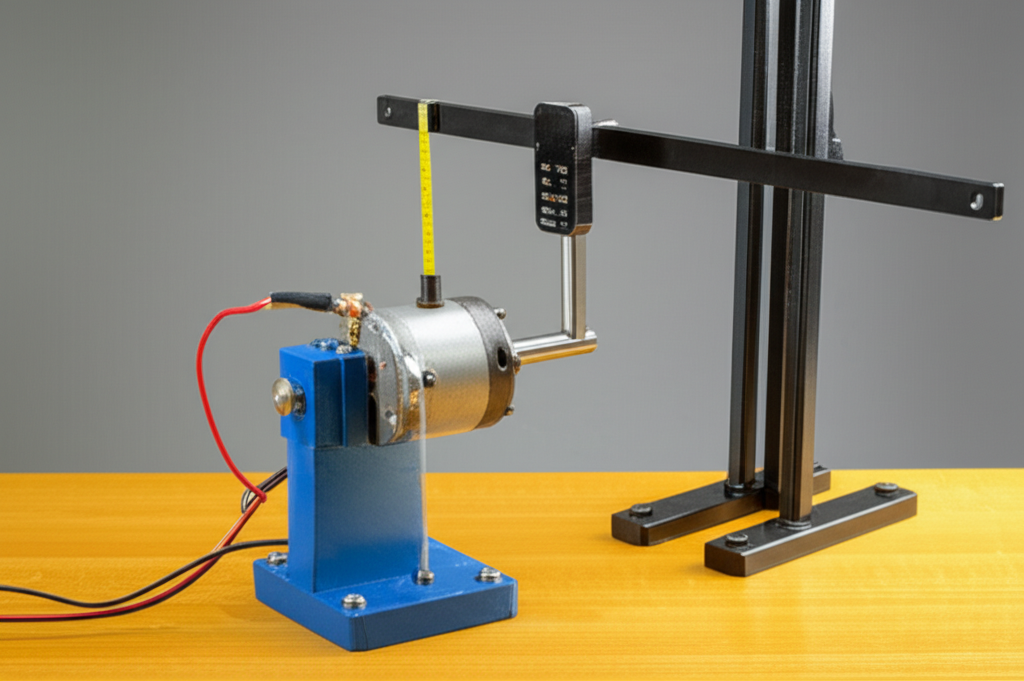

Tools and Methods for Measuring Motor Torque

You do not need a million‑dollar lab to measure torque. You do need a plan and safe fixturing.

- Dynamometer: the gold standard for direct torque and speed measurement. You get torque‑speed curves and efficiency maps

- Inline torque sensor: fits between motor and load. Great for development rigs

- Indirect method: measure current and speed then estimate torque using known constants and losses. This method works well for DC motors with known Kt and for servo systems that expose torque estimates

I also log temperature. If the winding runs hot you might be pushing torque past the safe continuous rating. A small fan can make the difference between a stressed motor and a happy one.

Common Mistakes and How I Troubleshoot Them

I keep a short list of traps that bite people.

- Unit mix‑ups: someone plugs HP into a kW formula or interpolates a curve in ft‑lb while the spreadsheet expects Nm

- Ignoring efficiency: they use input power in the torque formula without multiplying by η

- Forgetting gearbox efficiency: they multiply by ratio then forget the 85% or 90% loss factor

- Confusing input vs output torque: the motor makes Tin but the shaft after a gearbox sees Tout

- Overlooking dynamic torque: steady state looks fine then the system fails during acceleration or start

- Misreading datasheets: peak torque is not continuous torque and holding torque on a stepper is not torque at 1000 RPM

My go‑to troubleshooting approach:

- Verify units everywhere

- Recalculate torque at the exact operating speed and duty cycle

- Measure current and temperature

- Check alignment and friction sources

- Reread the torque‑speed curve and the nameplate

- Confirm that the control strategy matches the load type

Real-World Examples and Numbers You Can Use

Let me share a few simple cases and rules of thumb that I lean on.

Example 1: Power‑to‑Torque quick math

- A 1 kW motor at 1500 RPM

- T = (1 × 9549) / 1500 ≈ 6.37 Nm

- Add a 20:1 gearbox with 90% efficiency

- Output torque ≈ 6.37 × 20 × 0.90 ≈ 114.7 Nm

- Output speed ≈ 1500 / 20 = 75 RPM

- That combination shows why gear reduction is so powerful

Example 2: Conveyor torque

- Move a 200 kg load horizontally at steady speed

- Belt friction coefficient ~ 0.2

- Drive pulley radius = 0.15 m

- Force = m g μ = 200 × 9.81 × 0.2 ≈ 392.4 N

- T_required at pulley = F × r ≈ 392.4 × 0.15 ≈ 58.9 Nm

- If your motor drives the pulley directly you need at least that torque plus a safety factor

- If you use a gearbox then compute motor torque as Tmotor = Tpulley / (ratio × η)

Example 3: Estimating torque from a nameplate

- Nameplate shows 3 HP at 1750 RPM

- T ≈ (3 × 5252) / 1750 ≈ 9.0 ft‑lb ≈ 12.2 Nm

- If the nameplate efficiency is 90% then that torque is already a mechanical number since HP is often rated at the shaft

- If you only know electrical input power then apply efficiency first

Quick ranges I see out there:

- Small hobby DC motors: 0.005 to 0.2 Nm

- Cordless drill motors: 10 to 50 Nm peak at the chuck with gearbox

- 10 HP industrial AC motor: roughly 70 to 80 Nm rated

- EV traction motors: 250 to 500+ Nm peak at the motor shaft and far more at the wheels through gearing

Efficiency vs load rule:

- Most motors hit best efficiency between 75% and 100% of rated load

- Running at 20% load hurts you on efficiency and power factor

- I try to size so the operating point sits near the flat top of the efficiency curve

One more note on the mechanical stack. The magnetics and laminations inside the machine shape torque production. I have seen two motors with the same frame and power rating behave differently under ripple‑sensitive loads because one had superior lamination design. Better laminations cut eddy losses and can improve torque consistency at low speed.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the relationship between torque and horsepower?

- Power connects torque and speed. P = T × ω

- In practical units use T (Nm) = (P (kW) × 9549) / RPM or T (ft‑lb) = (HP × 5252) / RPM

- Double speed with the same power and torque halves. Double torque at the same speed and power doubles

How can I estimate torque from a motor’s nameplate?

- If the nameplate lists output power and rated RPM then plug into the power‑to‑torque formula

- If you only know electrical input power then multiply by efficiency first to get mechanical output power

- Watch your units and remember that kW uses 9549 and HP uses 5252

Why does a motor’s torque change with speed?

- Induction motors depend on slip. Torque rises with slip to a peak then drops near breakdown

- DC and BLDC motors lose available current at high speed due to back EMF which drops torque unless the drive raises voltage

- Cooling and thermal limits also constrain continuous torque at low speed on some frame types

What is the difference between static and dynamic torque?

- Static torque holds a load at rest. Think holding torque on a stepper or stall torque on a DC motor

- Dynamic torque includes acceleration and deceleration components. It must overcome inertia and friction during motion

- You size for both. Hold the load without overheating and still hit your acceleration targets

How do gear ratios change torque?

- Gears multiply torque by the gear ratio then subtract losses due to efficiency

- Speed drops by the same ratio

- Always include gearbox efficiency in your math

What changes when I add a VFD?

- You gain speed control and better match the operating point to the load

- Torque delivery improves at low speed with vector control and encoder feedback

- Do not assume a VFD raises the continuous torque rating beyond the motor’s thermal limit

How do lamination materials affect torque and efficiency?

- Better laminations reduce core losses and heat

- High quality stator and rotor laminations can reduce torque ripple and improve low speed smoothness

- The manufacturing and material of these parts matter so I pay attention when comparing motors

If I only know current on a DC motor can I get torque?

- Yes if you know Kt

- T = Kt × I works well within the linear region

- Watch temperature and continuous current ratings to protect the winding

Final Thoughts and a Quick Checklist

Torque calculations are not mysterious. They are a set of tools you can apply with confidence once you know what information you have. I start with the simplest path.

- Do you know power and speed? Use T = P × 9549 / RPM in SI or T = HP × 5252 / RPM in Imperial. Apply efficiency first if you start from electrical input

- Do you know force and radius? Use T = F × r then add acceleration and friction as needed

- Do you have a DC or BLDC motor with Kt? Use T = Kt × I and keep an eye on thermal limits

- Do you have a gearbox? Multiply by ratio and by gearbox efficiency

- Are you near the continuous torque limit? Check temperature and duty cycle

- Are you mixing units? Stop and convert then recompute

I have one more practical tip. When torque calculations and reality do not line up I look inside the machine. The internal magnetic circuit can tell a story. The quality of laminated steel and the way the stator and rotor are stacked affects loss and torque smoothness. If you want to see how these parts come together in modern builds you can browse motor core laminations. You already saw how better laminations reduce losses and sharpen performance which ties directly back to torque at the shaft.

If you want a single takeaway it is this. Torque is just power and speed in a different suit. Match the formula to your knowns. Respect efficiency and dynamics. Read the curves and do the math twice. Your motor will thank you with quiet operation and cool bearings.

Internal links used in this article:

- motor principle: https://nfdyzyo.top/motor-principle/

- stator core lamination: https://sinolami.com/stator-laminations/

- rotor core lamination: https://sinolami.com/rotor-laminations/

- electrical steel laminations: https://sinolami.com/electrical-steel-laminations/

- motor core laminations: https://sinolami.com/motor-core-laminations/