How to Tell if Your Fan Motor Fuse is Blown: A Step-by-Step Diagnostic Guide

- Table of Contents

- Introduction: Is Your Fan Not Working?

- Safety First: The Precautions I Never Skip

- Quick Checks Before You Touch a Fuse

- Where I Find Fan Motor Fuses in Real Life

- HVAC Systems

- Cars and Trucks

- Home Appliances

- Visual Inspection: What a Blown Fuse Looks Like

- The Definitive Multimeter Test: My Go-To Method

- If the Fuse Is Blown: What That Really Means

- Replacing the Fuse the Right Way

- When I Call a Professional Technician

- Case Studies From My Notebook

- HVAC Blower Fan Not Turning On

- Car AC Fan Not Blowing

- Bathroom Exhaust Fan Failure

- Costs, Tools, and Realistic Expectations

- Preventive Tips That Save Fuses

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Conclusion: Diagnose With Confidence

Introduction: Is Your Fan Not Working?

I know that sinking feeling. You flip the switch on the AC or set the thermostat to “Cool” and nothing moves. Maybe your furnace fan won’t turn on. Maybe your car AC fan isn’t blowing. You start wondering if the motor died or if the entire system went belly up.

Before you assume the worst, check the simplest protection device in the circuit. The fan motor fuse. It often takes the hit when something goes wrong downstream. I’ve seen this play out in HVAC systems, cars, and home appliances. A blown fuse can stop a perfectly good fan from spinning. It can also point to a deeper electrical problem that needs attention.

In this guide I’ll walk you through exactly how I tell if the fan motor fuse is blown. I’ll show you where I find fuses, what I look for, how I test them with a multimeter, and what to do next. I’ll keep the steps practical and safe. You’ll see some real examples from my own repairs. By the end you’ll be able to diagnose a blown fuse with confidence.

Safety First: The Precautions I Never Skip

Electricity deserves respect. I follow these rules every time because they keep me safe.

- Disconnect power. Pull the plug on an appliance. Switch off the furnace power switch. Turn off the outdoor condenser disconnect. Remove the car key and disconnect the battery negative if needed. I treat power as live until I test it.

- Wear safety glasses and insulated gloves. I prefer thin electrical safety gloves for a good grip.

- Work in a dry area. No wet floors. No damp walls. No water nearby.

- Avoid touching bare metal. I use a fuse puller or insulated pliers when possible.

- Keep one hand behind my back when probing. It reduces the chance of current passing across my chest.

- Never bypass a fuse with wire or foil. That hack invites a fire.

I also keep a small ABC fire extinguisher nearby. I’ve never needed it during fuse testing, yet I like knowing it stands ready.

Quick Checks Before You Touch a Fuse

A blown fuse is a common culprit. It isn’t the only one. I knock out a few easy checks first. These quick steps often save time.

- Confirm power supply. Make sure the main power switch is on. Check the circuit breaker. If it tripped, reset it once. Breakers that trip again point to a short circuit or motor issue.

- Thermostat sanity check. For HVAC, set the thermostat to “Cool” or “Heat” and select “Fan On” or “Auto” with a temperature that will trigger the system. Wrong settings can mimic a failure.

- Visual fan inspection. Look for debris in a condenser fan. Check for dirt buildup on a blower wheel. Spin the fan blades gently by hand with power off. They should move freely with no scraping.

- Listen for clues. A humming motor that won’t spin often points to a failed capacitor or stuck bearings. Rapid clicking may indicate a relay or contactor issue. Silence can mean no power to the fan.

- Smell test. A burning odor or smoke signals trouble. I cut power right away and investigate wiring and motor windings.

If the fan still refuses to run, I move to the fuses.

Where I Find Fan Motor Fuses in Real Life

Fuses live in predictable places. The fuse you want depends on the system you’re working on. Here’s where I look.

HVAC Systems

- Furnace control board. Many furnaces use a small 3 to 5 amp blade fuse on the control board. It protects the low-voltage control circuit. If that fuse blows, the blower often won’t run.

- Outdoor condenser panel. Central AC units usually have fuses in the outdoor disconnect. These protect the high-voltage circuit. You may also find a smaller fuse for the condenser fan motor inside the unit’s electrical compartment.

- Near thermostat wiring. Shorted thermostat wiring can blow the low-voltage fuse on the control board. Check for scrapes or bare spots where wires pass through sheet metal.

Use the appliance’s wiring diagram or the panel label if available. I look for labels like FAN, BLOWER, A/C, COND FAN, or FURNACE. The owner’s manual always helps. If you have one, use it.

Cars and Trucks

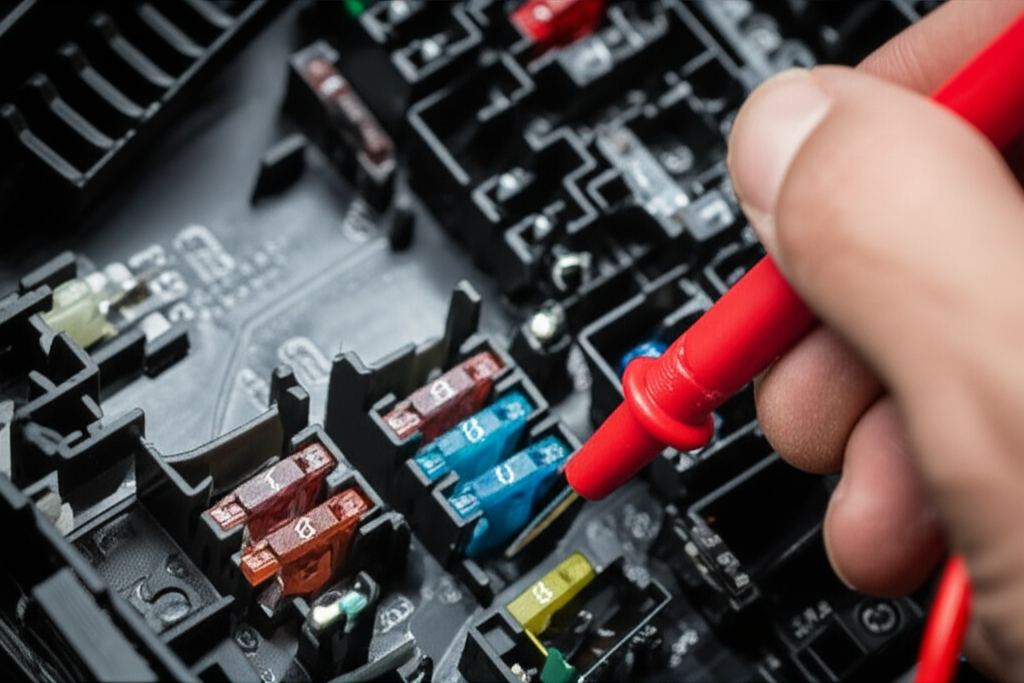

- Under-hood fuse box. Radiator fans, AC condenser fans, and blower motors often have dedicated blade fuses or maxi fuses under the hood. The cover usually has a fuse box diagram.

- Cabin fuse panel. The heater blower fuse or relay sometimes lives in the passenger compartment near the dash or kick panel. Look for labels like HTR, BLOWER, or FAN.

- Relays. A bad relay can mimic a blown fuse. If the fuse checks out, test or swap the fan relay with a known good one of the same type.

I always check the owner’s manual for the correct fuse location and rating. It saves time. It also prevents guesswork that can cost money.

Home Appliances

- Behind the control panel. Microwaves and ovens often hide glass or ceramic fuses behind the controls. You must remove screws to access them.

- Near the fan motor. Refrigerators and electric dryers may have thermal fuses or standard fuses protecting the fan circuit.

- Inside the main fuse area. Many appliances use one or more fuses near the power entry point or control board.

Again, the owner’s manual is your friend. It tells you fuse type, location, and rating. I don’t assume. I verify.

Visual Inspection: What a Blown Fuse Looks Like

I always cut power before I touch a fuse. Then I pull the suspected fuse with a fuse puller or insulated pliers. A visual inspection can solve the mystery in seconds.

Here’s what I look for by fuse type:

- Glass fuse. These look like tiny glass tubes with end caps. A good fuse has an intact metal filament inside. A blown fuse often shows a broken filament, a melted blob, or soot on the glass.

- Blade fuse. These common automotive style fuses have two metal blades and a colored plastic body. You can see a metal strip through the top window. If the strip is broken, melted, or the plastic shows burn marks or bulging, the fuse is blown.

- Cartridge fuse. These cylindrical fuses can be ceramic or glass. Some have visible windows. Others don’t. Many blown cartridge fuses show burn marks or a strong odor.

Visual checks help, yet they aren’t perfect. I’ve pulled fuses that looked fine then failed under a multimeter test. I call the multimeter the referee.

The Definitive Multimeter Test: My Go-To Method

A continuity test or resistance test takes the guesswork out. I use a simple digital multimeter. You don’t need a fancy model. You just need one that has continuity and ohms.

My step-by-step process:

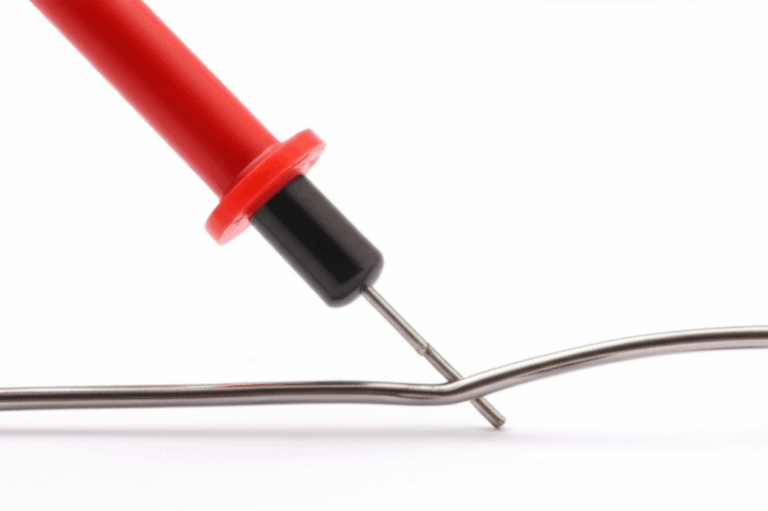

1) Remove the fuse from its socket. Testing in place can give false readings due to parallel paths.

2) Turn on the multimeter. I set it to continuity if the meter has an audible beep. If not, I set it to ohms (Ω).

3) Touch the probes together to confirm the meter works. You should hear a beep on continuity. You should see a near-zero resistance reading on ohms.

4) Place one probe on each metal end of the fuse. Hold them steady.

5) Read the result:

- Good fuse. The meter beeps on continuity. The ohms reading hovers near 0 Ω. You may see readings like 0.2 Ω or 0.3 Ω due to probe and fuse resistance.

- Blown fuse. The meter stays silent on continuity. You see OL or infinite resistance on ohms. That means open circuit.

That’s it. This quick test works on blade fuses, glass fuses, and cartridge fuses. It works on HVAC control board fuses and automotive fuses. It works on appliance fuses too. I rely on it every time.

If the Fuse Is Blown: What That Really Means

A fuse doesn’t blow for fun. It acts like a guard dog that barks when something crosses the line. Replace it blindly and you risk another failure. You also risk damage or fire if the real problem is severe.

In my experience, blown fan fuses come from a few common issues:

- Short circuits. Frayed wiring, rubbed-through insulation, a pinched wire under a panel, or an internal short in the fan motor windings can cause a direct short to ground. The fuse pops quickly to protect the rest of the circuit.

- Overcurrent or overload. The motor draws more current than normal. This happens when bearings seize, blades jam, airflow gets blocked by dirt, or the blower wheel binds. I also see overcurrent when a motor capacitor fails. The motor hums but won’t start which boosts current draw until the fuse gives up.

- Component failure. A bad relay or contactor can stick or chatter. That stress can blow a fuse in some designs. A failing thermostat circuit can short low-voltage wires and blow the furnace control board fuse.

- Wrong fuse rating. If someone installed a lower-amp fuse than specified, normal start-up current can blow it. That’s an easy fix once you catch it.

I always try to identify the root cause before I install a new fuse. It saves me from doing the same job twice.

Replacing the Fuse the Right Way

Once I confirm a blown fuse and I have a plausible cause addressed, I replace the fuse. I follow a few strict rules.

- Match the exact amperage rating. If the label says 10A, I use a 10A fuse. Nothing higher. A higher rating removes overcurrent protection and invites overheating.

- Match the fuse type. Blade for blade. Glass for glass. Slow-blow for slow-blow if specified. Fast-acting for fast-acting. The type matters because it affects how the fuse behaves during start-up current surges.

- Inspect the holder or socket. I look for heat damage, corrosion, or loose contacts. Burned fuse holders can create more heat and future failures.

- Restore power and monitor. If the new fuse blows immediately, I cut power again. There is a short circuit or a failed component that needs attention. If it holds and the fan runs, I still keep an eye on things for the next hours or days.

I never install a bigger fuse to get by. That quick fix can turn a small problem into a dangerous one.

When I Call a Professional Technician

I enjoy DIY work. I also know when to bring in a pro.

- The new fuse blows right away. That screams short circuit or a seized motor. You need deeper diagnostics that may involve live testing and component isolation.

- I smell burning insulation or see smoke. I stop immediately and call a tech.

- I can’t identify the root cause. Guessing with electricity gets expensive and risky.

- The system is complex or high voltage. HVAC outdoor units and electric ovens carry risk. If I’m not sure, I get help.

- The motor hums and the capacitor tests fine. Some issues require specialized tools and training.

A good tech saves time and protects your equipment. I see the service call fee as insurance against bigger problems.

Case Studies From My Notebook

I’ll share three quick stories that show how this plays out in the real world.

HVAC Blower Fan Not Turning On

I got a call from a friend. The furnace wouldn’t blow air even though the thermostat clicked and the furnace lit. I cut power to the furnace, removed the blower door, and checked the control board. The small blade fuse on the board looked intact, yet the blower stayed silent. I pulled the fuse and tested it with my multimeter. OL. The fuse was blown.

Next question. Why did it blow? I inspected the low-voltage wiring. I found a spot where the thermostat wire had rubbed against a sharp edge on the furnace cabinet. The wire jacket wore through and shorted to the metal. That can blow the 3 to 5 amp control fuse in a flash. I repaired the wire with proper splices and protective grommet. Then I replaced the fuse with the exact same rating.

Power on. Thermostat to “Fan On”. The blower roared to life. We monitored the system for a day with no further issues.

Car AC Fan Not Blowing

My own car once lost the cabin blower on a hot day. No air from the vents. I checked the owner’s manual for the blower fuse location. The under-hood fuse box had a labeled slot for HTR/BLWR. I pulled the blade fuse and checked it. The metal strip had a clear break. I replaced it with the same amp rating.

The fan ran again, yet it sounded off at low speed. I suspected a failing blower motor resistor or a blower motor drawing extra current. I tested the blower motor current with a clamp meter and compared it to specs. It ran high at certain speeds. I decided to replace the blower motor since it was on its way out. The new motor pulled proper amperage and the problem never returned.

Bathroom Exhaust Fan Failure

An older bathroom exhaust fan stopped working after years of service. I killed power at the breaker and opened the housing. I found a small inline glass fuse tucked near the motor wiring. The filament had clearly melted. The fan wheel was packed with dust and hair which increased load and current draw. I cleaned the housing and wheel. The motor spun freely by hand after cleaning.

I matched the fuse type and amperage, then reassembled the fan. Power on. It worked. Lesson learned. Restricted airflow and dirt can kill fuses and motors slowly.

Costs, Tools, and Realistic Expectations

Tools I keep ready:

- Digital multimeter with continuity and ohms. A basic model works fine.

- Fuse puller or needle-nose pliers with insulated handles.

- Replacement fuses. I carry a small assortment of blade fuses, glass fuses, and cartridge fuses in common ratings.

- Insulated gloves and safety glasses.

- Screwdriver set for panel access.

- Owner’s manual or service guide.

Costs I see often:

- Fuses run cheap. Most cost between $1 and $10 depending on type and rating.

- A multimeter runs $15 to $50 for a basic unit.

- Professional diagnostics range from $75 to $200 as a service call fee in many areas. Parts and labor add to that if deeper repairs are needed.

- If the motor or capacitor failed, you might see $150 to $800+ depending on system and parts.

Expectation check:

- Visual inspection and a multimeter test solve fuse questions fast. You can confirm good vs blown in minutes.

- Finding the root cause can take longer. Shorts hide in wiring harnesses. Motors can fail intermittently. Relays can chatter under load.

- If a new fuse blows quickly, stop. A persistent fault needs proper repair.

Preventive Tips That Save Fuses

A little prevention reduces blown fuses and keeps fans happier.

- Keep blades and blower wheels clean. Dirt acts like a brake. It increases current draw and heat.

- Maintain airflow. Replace air filters on schedule. Clear leaves and debris around outdoor condenser units. Check for blocked vents or grilles.

- Inspect wiring at stress points. Look where wires pass through metal. Add grommets or loom where needed.

- Replace weak capacitors. A failing run capacitor will make a motor hum and stall. It also pushes current up which can blow fuses.

- Check vibration. Loose mounts let motors shake which rubs wires and stresses bearings.

- Verify proper fuse ratings. Wrong fuses fail too soon or too late. Neither is good.

Frequently Asked Questions

- How do I know if a fuse is blown without a multimeter?

- Look for a broken metal strip in a blade fuse or a broken filament in a glass fuse. It works sometimes. It misses hidden failures. I still recommend a multimeter continuity test for accuracy.

- My fan motor hums but won’t spin. Could the fuse be the problem?

- If it hums, you have power past the fuse. The fuse is likely good. The issue could be a failed capacitor or seized motor bearings. Cut power and investigate.

- Can I use a higher amp fuse to stop nuisance blowing?

- No. A higher fuse rating removes protection. It increases the risk of melted wiring and fire. Find and fix the root cause instead.

- Where is the fan fuse located in my specific appliance or car?

- Check the owner’s manual. Look for a fuse box diagram or wiring diagram. For cars, the fuse box cover usually lists fuse numbers and functions. For HVAC, check the furnace control board and the outdoor unit’s electrical panel.

- What’s the difference between a blown fuse and a tripped breaker?

- A breaker can reset. A fuse must be replaced. Both protect against overcurrent. Breakers respond mechanically. Fuses respond by melting their internal link.

A Simple Primer on Motors and Why Fuses Matter

Fans rely on electric motors. Those motors have stationary parts and rotating parts. If you want a friendly overview, this explainer on stator and rotor gives helpful context. When insulation inside the motor breaks down, you can get shorted windings. That spikes current which blows the fuse.

Motor design and materials also influence heat and efficiency. Better laminations reduce eddy current losses which lowers heat and helps reliability. If you want to see what I mean, skim this page on motor core laminations. It’s not required for troubleshooting. It does explain why some motors run cooler and last longer.

If you’re curious about the stationary magnetic core specifically, this overview of stator core lamination shows how careful design reduces losses. Less loss means less heat. Less heat means less stress on the electrical system which also means fewer nuisance fuse failures in tight designs.

Finally, if you’re troubleshooting a persistent fan motor issue and want a structured approach, this guide on diagnosing a motor problem walks through common failure patterns. I use similar logic when I chase intermittent faults that love to hide.

Putting It All Together: My Diagnostic Flow

When I face a fan not working, I walk through a simple flow. You can copy this pattern.

1) Confirm power and settings.

- Check the main switch and breaker. Reset a tripped breaker once and then stop if it trips again.

- For HVAC, verify thermostat mode and temp. Set “Fan On” for a direct blower test.

2) Observe and inspect.

- Listen for humming, clicking, or silence.

- Smell for burning odor.

- Spin the fan by hand with power off. It should move freely.

- Remove debris and clear airflow restrictions.

3) Find the fuse.

- HVAC. Check the furnace control board fuse and the outdoor disconnect and panel.

- Automotive. Check under-hood and cabin fuse boxes by the diagram.

- Appliances. Check near the control panel, near the motor, or at the main fuse area.

4) Test the fuse.

- Pull the fuse with power off.

- Use a multimeter for continuity or resistance.

- Confirm blown vs good.

5) If blown, hunt the cause.

- Inspect wiring for shorts or chafing.

- Check the motor capacitor for HVAC and appliances.

- Look for seized bearings or blocked blades.

- Check relays and contactors for sticking or arcing.

6) Replace with the exact same fuse type and AMP rating.

- Inspect the socket for heat damage or corrosion.

- Restore power and test operation.

7) If the new fuse blows or the fan still fails, call a pro.

- You likely have a short to ground, an open circuit in the wrong place, or a dead component.

This sequence keeps me safe. It keeps me efficient. It also keeps me from throwing parts at a problem.

Deeper Dive on Causes: What I See Most

- Short to ground in wiring. I see this in cars where harnesses rub on brackets. I see it in furnaces where thermostat wires pass through sharp metal. I look for corroded terminals and loose connections too since heat and oxidation increase resistance and create hot spots.

- Motor overload. Dirty blower wheels, clogged filters, and blocked vents raise static pressure. The fan works harder which draws more amperage. Fuses blow in marginal situations.

- Capacitor failure. Single-phase AC motors rely on capacitors for start or run phases. A failed run capacitor often gives you a humming motor that won’t spin. The current rises and can blow a fuse if protection sits upstream.

- Relay or contactor faults. Pitted contacts increase resistance and heat. Sticking contacts can cause unexpected motor behavior. Both stress the circuit.

- Wrong or tired fuse. I find undersized fuses after someone guessed during a late-night repair. I also find old fuses with corroded ends that drop voltage. Replace questionable fuses even if they test okay because corrosion can mask trouble.

Electrical schematics help tie these clues together. I like to sketch a quick circuit diagram when I chase a stubborn problem. It keeps me methodical.

Special Notes by System Type

- HVAC blower motors. The furnace control board fuse protects low-voltage controls. If it blows, look at thermostat wiring and accessory circuits first. Blower motors and capacitors still fail often. Check airflow too since a dirty filter can force the motor to labor.

- Outdoor condenser fans. You may find issues at the contactor or the run capacitor. Louvered panels can pinch wires during reassembly. I inspect those paths carefully.

- Automotive radiator and AC fans. Relays and temperature switches play a big role. I’ve solved “fan not spinning” by replacing a bad relay more than once. The fuse tells you power protection tripped. The relay can be the root cause. This is why I don’t stop after the fuse swap.

- Appliances. Microwaves and ovens use high-voltage parts. Many also have thermal fuses. Those protect against overheating, not short circuits. If a thermal fuse is open, find the reason for the heat. Blocked vents, dead cooling fans, or failed thermostats can sit at the root.

Signals That Help Me Decide

- Humming motor plus good fuse. Likely capacitor or seized bearings.

- No sound plus blown fuse. Likely shorted wiring or motor windings. Could be a control board short on HVAC.

- Clicks with no motion and good fuse. Likely relay or contactor not switching power through. Could be low voltage supply issues too.

- Burning smell or smoke. Stop. Disconnect power. Inspect for charred insulation or melted connectors.

Final Reminders on Ratings and Types

Fuse ratings matter. I match the amperage rating exactly. I also match the type.

- Blade fuses. Common in automotive and some appliances. Ratings are color coded. I still read the numbers to avoid mixups.

- Glass fuses. Often fast-acting. Used in older or specific appliances and electronics.

- Ceramic and cartridge fuses. Often higher interrupt ratings. Many are slow-blow to tolerate start-up surges.

- Slow-blow vs fast-acting. Motors draw extra current at startup. Many designs call for a slow-blow fuse. The service manual or label will tell you which one you need.

If the owner’s manual calls for a specific part number, I use it. It takes guesswork out of the equation.

Conclusion: Diagnose With Confidence

A fan that won’t run can ruin your day. A simple fuse test can turn it around fast. I always start safe. I confirm power and settings. I check for obvious issues like debris or airflow restriction. I find the fuse by the diagram or manual. I trust my multimeter for a continuity test because it settles the question.

If the fuse is blown, I don’t just slap in a new one. I look for short circuits, overloaded motors, failed capacitors, corroded terminals, or relay problems. I replace the fuse with the exact same amp rating and type. If it blows again, I stop and call a pro. That saves money and protects the system.

You can do this. You can find the right fuse. You can test it accurately. You can make smart calls about what comes next. Start with safety. Use your meter. Let the clues guide you. Then fix the root cause so the fuse protects your system instead of ending your day.