Hysteresis & Eddy Current Losses Explained: Causes, Impact, and Minimization

Every design engineer grapples with the critical challenge of maximizing motor and transformer efficiency while keeping a close eye on production costs and thermal management. If you’ve ever found yourself weighing the trade-offs between different core materials or wondering why a perfectly designed device is still getting hot and wasting power, you’re in the right place. The culprits are often two invisible energy thieves: hysteresis and eddy current losses.

These phenomena, collectively known as “core losses” or “iron losses,” are fundamental hurdles in electromagnetic design. They are the unavoidable price of manipulating magnetic fields to generate motion and transfer power. Understanding them isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s essential for creating efficient, reliable, and cost-effective electrical machines. This guide will break down these complex topics into clear, actionable engineering principles to empower you to make more informed design decisions.

In This Article

- Understanding Core Losses: The big picture of energy loss in magnetic systems.

- Hysteresis Loss: A deep dive into the magnetic “memory” effect.

- Eddy Current Losses: Uncovering the unwanted electrical “whirlpools” in your core.

- Key Differences and Similarities: A head-to-head comparison.

- The Real-World Impact: Why these losses matter for performance and your bottom line.

- Minimization Techniques: A guide to selecting the right materials and design strategies.

- Practical Applications: Where these losses have the biggest impact.

- Your Engineering Takeaway: Key points to remember for your next project.

Understanding Core Losses in Electrical Systems

Before we dissect the two main types of loss, let’s zoom out. Whenever you use an alternating current (AC) to create a fluctuating magnetic field in a material—the very principle behind transformers, motors, and inductors—you will inevitably lose some energy. This energy doesn’t contribute to the useful work of the device. Instead, it converts directly into heat within the magnetic core.

This wasted energy is what we call core loss. It’s a critical factor because it directly dictates the efficiency, operating temperature, and ultimately, the lifespan of your component. Core loss is primarily the sum of two distinct phenomena: hysteresis loss and eddy current loss. While they both stem from the changing magnetic field, their physical origins are quite different. Getting a handle on both is the first step toward controlling them.

Hysteresis Loss: The Magnetic “Memory” Effect

What is Hysteresis Loss?

Imagine trying to rapidly bend a metal paperclip back and forth. You’ll notice it gets warm at the bend. Why? You’re expending energy to overcome the internal friction and restructure the metal’s grain. Hysteresis loss is conceptually similar; it’s a form of “magnetic friction.”

It is the energy consumed to repeatedly reorient the magnetic domains within a core material as the magnetic field rapidly switches direction. This energy is lost as heat in every single AC cycle.

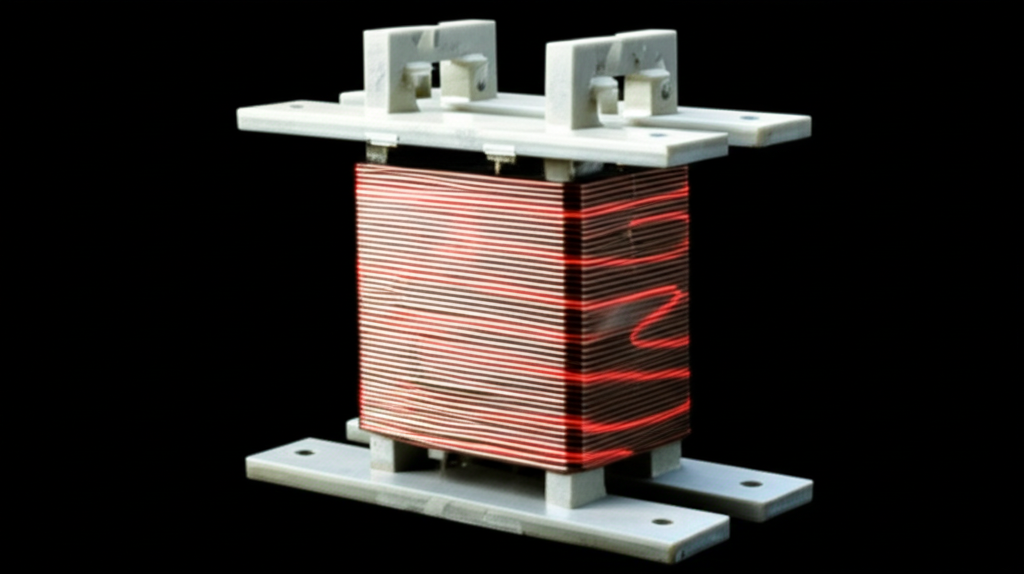

The Physical Mechanism: A World of Tiny Magnets

To understand hysteresis, you need to think of a magnetic material like iron as being composed of countless microscopic regions called magnetic domains. You can picture each domain as a tiny, powerful bar magnet with its own north and south pole.

Visualizing Hysteresis with the B-H Curve

Engineers visualize this process using a B-H curve, or a hysteresis loop.

- H (Magnetic Field Strength): This is the “effort” you apply with your electrical coil.

- B (Flux Density): This is the “result”—how strongly the material becomes magnetized.

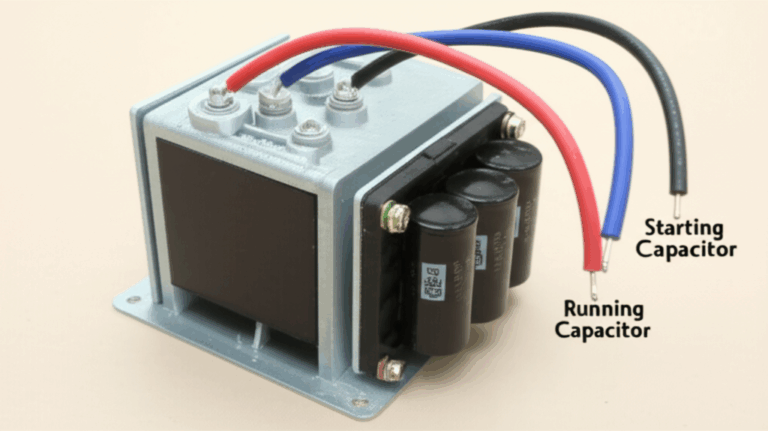

! Two key terms from the B-H loop are retentivity (the residual magnetism left after the external field is removed) and coercivity (the amount of reverse field needed to bring the magnetism back to zero). For low hysteresis loss, you want a material with low coercivity. Hysteresis loss isn’t constant. It’s influenced by: Now let’s switch gears from magnetic friction to an electrical phenomenon. If hysteresis loss is like a paperclip getting warm from bending, eddy current loss is like the heat generated in an induction cooktop. Eddy current loss is the energy lost due to circulating currents induced within the body of a conductive magnetic core. These currents are a direct consequence of the changing magnetic field and serve no useful purpose, only generating heat through a process called Joule heating. The principle here was famously described by Michael Faraday. Faraday’s Law of Electromagnetic Induction states that any change in the magnetic field through a conductive loop will induce a voltage (electromotive force or EMF) in that loop. Eddy current loss is highly sensitive to a different set of parameters than hysteresis loss: Similarities: These losses are far from trivial. Their combined effect has significant engineering and economic consequences. Fortunately, engineers have developed effective strategies to combat both types of core loss. The approach is a two-pronged attack focused on material selection and geometric design. Since hysteresis is an intrinsic property of a material, the primary solution is to choose the right one. The goal is to select a soft magnetic material with a very low coercivity—a “skinny” B-H loop. The fight against eddy currents is primarily won through clever physical design. The goal is to obstruct the paths these currents want to take. Understanding and managing core losses is crucial across a wide range of electrical equipment: Hysteresis and eddy current losses are two sides of the same coin—the coin of core loss in AC magnetic devices. While they are often discussed together, it’s critical to remember their distinct origins and, therefore, their distinct solutions. Here’s the summary to carry into your next design meeting: These losses are an ever-present challenge, but they are not insurmountable. Through careful material selection, thoughtful geometric design, and a solid understanding of the underlying physics, you can effectively manage their impact. This empowers you to build more efficient, cooler-running, and longer-lasting electrical systems. If you’re tackling a specific design challenge, consulting with specialists can help you navigate the trade-offs and select the optimal core solution for your application’s unique demands.Factors Affecting Hysteresis Loss

Eddy Current Losses: Induced Currents Fighting the Flux

What are Eddy Current Losses?

The Physical Mechanism: Faraday’s Law at Work

Factors Affecting Eddy Current Loss

Key Differences and Similarities: Hysteresis vs. Eddy Currents

Feature Hysteresis Loss Eddy Current Loss Origin Magnetic “friction” from reorienting magnetic domains. Electrical currents (I²R loss) induced by a changing magnetic field. Governing Principle Magnetic domain theory, B-H loop characteristics. Faraday’s Law and Lenz’s Law of electromagnetic induction. Primary Material Property Coercivity. Low coercivity is desired. Resistivity. High resistivity is desired. Primary Geometric Factor Minimal dependence on part geometry. Thickness. Loss is proportional to thickness squared. Frequency Dependence Proportional to frequency ($f$). Proportional to the square of frequency ($f^2$). Flux Density Dependence Proportional to $B_{max}^x$ (x ≈ 1.6-2). Proportional to the square of flux density ($B_{max}^2$). Impact of Hysteresis and Eddy Current Losses

Minimization Techniques: Reducing Core Losses

Reducing Hysteresis Loss: The Material Solution

Reducing Eddy Current Loss: The Geometric Solution

Practical Applications and Significance

Your Engineering Takeaway