Is an Engine a Motor? Deciphering the Terminology

Table of Contents

- The Short Answer: Not Always, But Often Interrelated

- Defining “Engine”: What Is It, Really?

- Core Function

- Energy Source

- Examples

- Defining “Motor”: A Broader Category

- Core Function

- Energy Source

- Examples

- The Crucial Differences: Engine vs. Motor

- Primary Energy Source

- Energy Conversion Type

- Technical Specificity

- Where Do They Overlap? The “Prime Mover” Concept

- Both Are Prime Movers

- Interchangeable in Colloquial Use

- Technical vs. Everyday Language

- Common Usage and Contextual Examples

- When to Use “Engine”

- When to Use “Motor”

- A Note on Etymology: How the Words Evolved

- Key Takeaways: Simplifying the Distinction

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Conclusion: Clear Terms for Clear Thinking

I used to lump engines and motors together without a second thought. I grew up hearing “car motor,” “fan motor,” “jet engine,” “diesel engine,” and I assumed they all meant the same thing with different decorations. Then I started working with technicians and engineers. That is when I learned why the question “Is an engine a motor?” comes up so often. It sounds simple yet it hides a useful distinction. You can still talk like a normal human and call the engine in your car a motor. People will understand you. In technical contexts though, your word choice matters because it points to the kind of energy conversion taking place.

Let me walk you through what I learned, what I got wrong at first, and how I explain it now. I will keep this practical and friendly. I will use examples you recognize. You will leave with a clear mental picture that sticks.

The Short Answer: Not Always, But Often Interrelated

Here is the short version I share with friends. An engine is a type of motor, yet not every motor is an engine. Think of “motor” as the umbrella. It covers any device that converts some form of energy into mechanical energy, torque, or motion. An engine sits under that umbrella as a specific kind of motor that uses heat or combustion to do that conversion.

So yes, engines and motors both produce mechanical energy. They just start from different energy sources and rely on different physical principles.

Defining “Engine”: What Is It, Really?

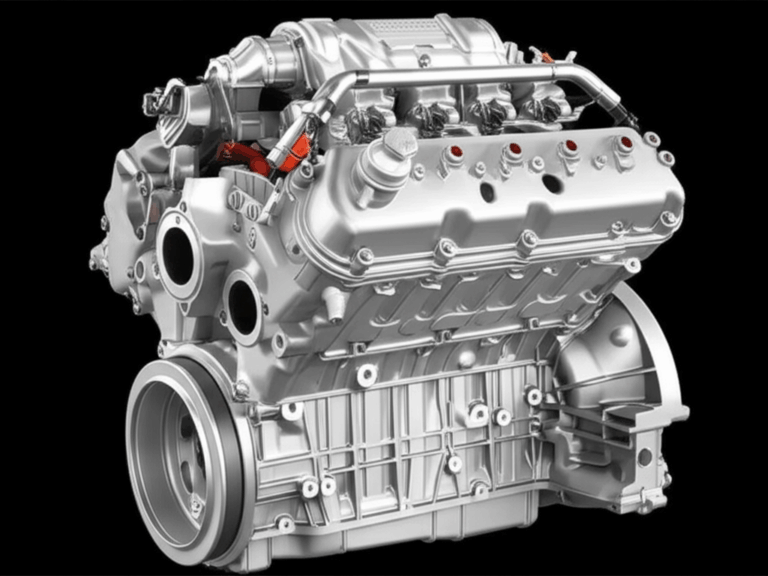

When I say “engine,” a picture of a car’s internal combustion engine probably pops into your head. That is a good start because internal combustion is the most common engine type around you. It is not the only one.

Core Function

An engine converts chemical or thermal energy into mechanical energy. That is the essence. In a gasoline or diesel engine, chemical energy stored in fuel becomes heat through combustion, then pressure, then motion through pistons and a crankshaft. In a steam engine, thermal energy in steam drives a piston or turbine.

This makes an engine a heat engine in broad terms. Heat goes in. Work comes out.

Energy Source

Engines typically consume fuel. Gasoline, diesel, kerosene for jets, natural gas in generators, heavy fuel oil for ships. Some engines use external heat sources. A steam engine burns fuel in a boiler outside the working cylinder. A Stirling engine uses a temperature difference across its chambers with external combustion or even solar heat.

So the energy source for engines lives in fuel or heat. Combustion or significant heat input drives the show.

Examples

- Internal Combustion Engine: The car engine under your hood. This includes gasoline spark-ignition, diesel compression-ignition, and the Wankel rotary engine.

- Diesel Engine: Used in trucks, ships, generators.

- Jet Engine: A gas turbine that compresses air, mixes it with fuel, ignites it, and then accelerates the exhaust to produce thrust.

- Gas Turbine: Used for power plants and aircraft. It is a form of heat engine.

- Steam Engine and Steam Turbine: External combustion with a boiler. Think locomotives and power generation.

- Stirling Engine: External combustion heat engine that runs on temperature differences.

I learned to think about engines through thermodynamics because it explains how heat transforms into useful work. That framing clears up a lot of confusion right away.

Defining “Motor”: A Broader Category

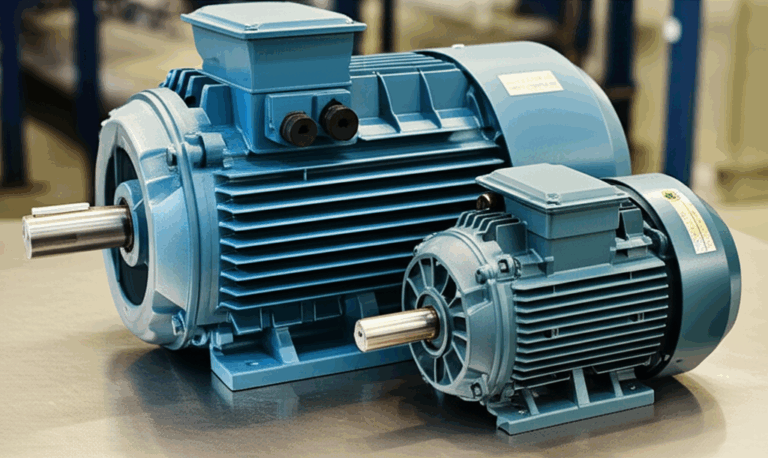

I reach for “motor” when the device converts electricity or fluid pressure into motion. It is the broader, more general word. Motors show up in your life every day, often in quiet ways.

Core Function

A motor converts any form of input energy into mechanical energy. It might be electrical, hydraulic, or pneumatic. The essence is conversion into torque or motion.

- Electric motors rely on electromagnetism. Current creates a magnetic field. That field interacts with a fixed stator field and turns a rotor. That motion spins a shaft, which does work.

- Hydraulic motors convert pressurized fluid into rotational motion.

- Pneumatic motors use compressed air to create movement.

These are not heat engines. They do not rely on combustion or heat. They rely on electromagnetic forces or fluid dynamics.

If you want a clean primer on how electromagnetic motors create torque, I like pointing people to a clear overview of the motor principle. It shows how magnetic fields and current combine to produce motion without jumping into heavy math.

Energy Source

- Electric motors: Electricity from a battery, inverter, or grid.

- Hydraulic motors: Pressurized oil from a pump.

- Pneumatic motors: Compressed air from a compressor.

No combustion required.

Examples

- Electric Motor: Fans, washing machines, power tools, elevators, and the traction motors in an Electric Vehicle.

- Hydraulic Motor: Excavators, winches, industrial drives.

- Pneumatic Motor: Air tools and actuators in factories.

Inside many of these motors you will find a stator and a rotor. The stator holds the stationary magnetic field. The rotor carries conductors or permanent magnets and spins inside that field. If you want a quick visual refresher on the two, this primer on the stator and rotor lays it out in plain terms.

The Crucial Differences: Engine vs. Motor

Here is how I now draw the line. It is simple and it holds up.

Primary Energy Source

- Engine: Fuel or heat.

- Motor: Electricity or pressurized fluid.

That one line solves most debates.

Energy Conversion Type

- Engine: Combustion and thermodynamics. Heat to mechanical work through pressure changes, expansions, and cycles.

- Motor: Electromagnetism, hydraulic fluid dynamics, or pneumatic pressure. Force and motion without burning fuel inside the working parts.

If heat and combustion drive it, I call it an engine. If electromagnetism or fluid pressure drive it, I call it a motor.

Technical Specificity

“Motor” is the broader term. “Engine” is a more specific term. In engineering contexts, an engine is a type of motor. In everyday speech, the words often blur because cars popularized the phrase “motor car.” That history sticks.

Where Do They Overlap? The “Prime Mover” Concept

When I first heard the phrase “prime mover,” I thought it sounded grand. Turns out it is a tidy way to explain the overlap.

Both Are Prime Movers

A prime mover is any device that converts energy into mechanical work to start motion in a system. Engines and motors both fit. They are both prime movers. They both sit at the front of a drivetrain or machine and push everything else into action.

Interchangeable in Colloquial Use

Language evolves. People say “car motor” in everyday speech. Mechanics talk about “motor mounts” even when they work on internal combustion engines. The phrase “motor vehicle” stuck from the early days of the “motor car.” It is all fine in conversation because context clears it up.

Technical vs. Everyday Language

In technical writing or engineering specs, I pick the precise word. I say “electric motors” when I mean electromagnetism. I say “internal combustion engines” when I mean fuel and thermodynamic cycles. That precision avoids confusion and sets expectations about fuel, performance, emissions, and controls.

Common Usage and Contextual Examples

When do I use one term over the other? Here is how I choose without overthinking it.

When to Use “Engine”

- Automotive, but only for gasoline and diesel internal combustion.

- Aircraft propulsion systems such as jet engines and turboprops.

- Marine power for ships that burn fuel.

- Power generation units that burn fuel such as gas turbines and reciprocating generator engines.

- Historic tech such as steam engines and steam turbines.

Example: “The diesel engine in that generator produces 2 MW at full load.”

When to Use “Motor”

- Electric Vehicles. The traction unit is an electric motor, not an internal combustion engine.

- Home appliances such as washers, dryers, fans, and vacuum cleaners.

- Industrial machinery that uses electric, hydraulic, or pneumatic drive.

- Robotics and actuators that produce motion from electric or fluid power.

Example: “This EV has a rear permanent magnet synchronous motor with 250 kW peak power.”

With EVs I still hear “electric engine.” I know what people mean. I say “electric motor” because it is more accurate and it helps the conversation when you talk about torque curves, inverters, and battery management.

A Note on Etymology: How the Words Evolved

I enjoy the word roots because they explain the confusion without scolding anyone. “Engine” comes from Latin ingenium, which means a clever device or invention. It once covered all sorts of contraptions, including siege engines and complex mechanical devices. The word then narrowed as steam engines and internal combustion engines took over heavy work.

“Motor” comes from Latin movere, to move. It described anything that causes motion. That broad meaning stuck when early cars were called motor cars. Marketing and common speech did the rest.

The two streams crossed and stayed crossed. Now we live with both.

Key Takeaways: Simplifying the Distinction

Whenever I teach this to someone new, I distill it down to three statements.

- An engine is a type of motor.

- Engines usually rely on combustion or heat, which makes them heat engines.

- Motors are the broader category for devices that create motion from electricity, hydraulics, or pneumatics.

That is it. Clean and simple.

Digging Deeper: How Engines and Motors Work

You do not need to memorize equations to grasp the core ideas. A few clear examples help.

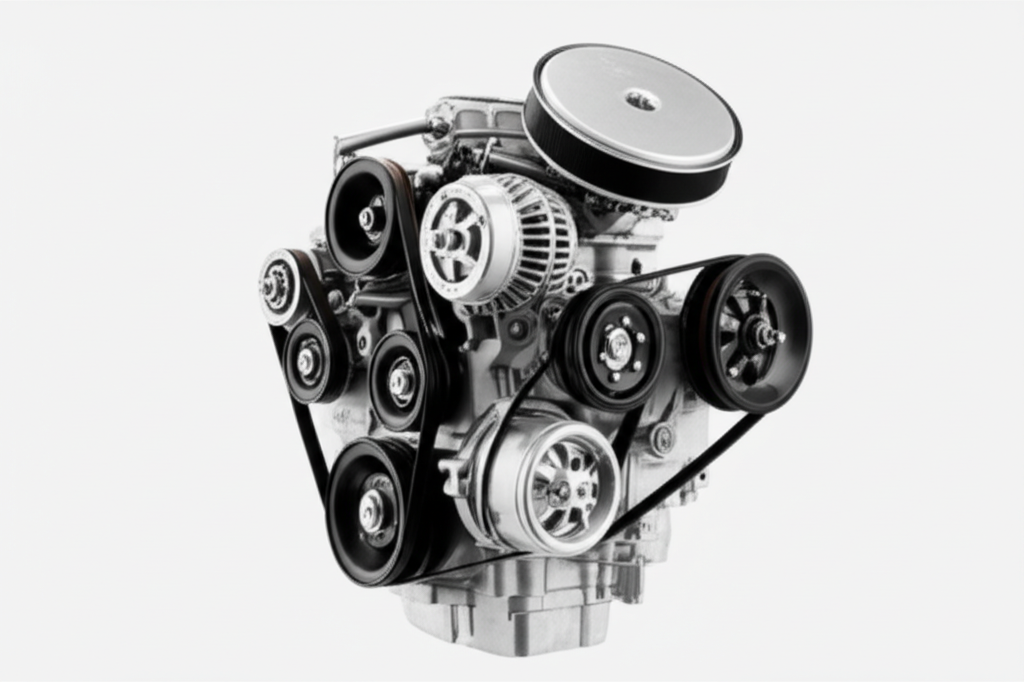

- Internal combustion engine vs. electric motor: The engine burns fuel in cylinders. Pistons move. A crankshaft turns. In the motor, current makes a magnetic field. That field interacts with another field in the stator. The rotor turns. No combustion. No exhaust. The two devices deliver torque to a shaft, yet they do it by different paths.

- Internal vs. external combustion: Internal means fuel burns inside the working chamber like a gasoline or diesel engine. External means fuel burns outside and transfers heat to a working fluid such as steam.

- Jet engine vs. gas turbine generator: They share a core turbine. In a jet, the turbine drives a compressor and the thrust pushes the aircraft forward. In a power plant, the turbine drives an electrical generator through a shaft.

- Hydraulic vs. pneumatic motor: Both use pressurized fluid. Hydraulic uses oil and delivers higher torque at lower speeds. Pneumatic uses air and is lighter and cleaner for tools.

I keep one more mental picture. In electric motors, the stator and rotor often use laminated steel cores to guide magnetic flux. Those laminations reduce eddy current losses and improve efficiency. If you are curious about that detail, this short overview of stator core lamination shows why those stacked sheets matter in real designs. The materials and geometry quietly shape performance.

Even the type of electrical steel affects loss and heat. I learned how manufacturers pick grades for different frequencies and loads because it drives efficiency and noise. If you want to peek under the hood without drowning in jargon, this primer on electrical steel laminations gives a friendly tour of the materials that make motors hum.

Practical Comparisons You Can Feel

Numbers help, yet I like comparisons you can feel.

- Startup behavior: Electric motors deliver max torque at zero rpm in many designs. That is why EVs leap off the line. Internal combustion engines build torque with revs and gearing. You feel a torque curve and shifts.

- Responsiveness: Motors respond instantly to current commands. Engines lag a bit because fuel burns and gases move. Turbochargers add more lag until boost arrives.

- Efficiency: Electric motors usually convert electrical energy to mechanical energy with very high efficiency. Internal combustion engines lose more energy as heat. You feel this as heat under the hood and hot exhaust.

- Maintenance: Electric motors have fewer moving parts and no oil changes. Engines have valves, injectors, fuel pumps, timing chains, and exhaust systems. Maintenance follows that complexity.

All of this traces back to the energy conversion method. Heat cycles versus electromagnetic force.

Power, Torque, and Units: How We Talk About Output

When people say “power” and “torque” they sometimes mix them up. I used to. Torque is the twisting force on a shaft measured in newton-meters or pound-feet. Power is the rate of doing work. In the SI system, power is measured in watts. Horsepower is a traditional unit used in automotive contexts. You can convert horsepower to watts. One mechanical horsepower equals about 745.7 watts.

Engines and motors both produce torque and power. We use the same units. The difference is how the device creates that output and how the torque curve looks across speed.

- Engines often have peak torque in a midrange band. Gearing keeps them in the sweet spot.

- Electric motors may have a flat torque curve across a wide rpm range. Control electronics shape that curve.

When I evaluate devices for a job, I match torque and power to the load and duty cycle. I care about the input energy too because that drives cost, range, emissions, and service.

Why the Words Get Mixed Up

You will still hear people ask, “Is a motor an engine synonym?” That question comes from history and habit.

- “Motor car” set a pattern in everyday speech.

- Early trade names and marketing blurred lines to reach buyers.

- People use “motor vehicle” in law and insurance.

- Some languages and regions use one word for both.

You do not need to correct anyone at a barbecue. You can switch terms for clarity when the conversation gets technical, especially when you compare electric vehicle motors with gasoline engines.

Real-World Contexts That Demand Precision

I learned to pick my words based on the industry setting.

- Automotive industry: Internal combustion engine for gasoline and diesel. Electric motor for EVs. Hybrid vehicles have both and the control system blends them.

- Aerospace industry: Jet engines and turbofan engines for aircraft. Electric motors for actuators or experimental electric propulsion.

- Manufacturing and robotics: Electric motors for conveyors, robots, and CNC machines. Hydraulic motors for high-torque tasks. Pneumatic motors for hand tools and quick actuators.

- Marine: Large diesel engines for propulsion. Electric motors for bow thrusters and hybrid drives.

Different industries also rely on different disciplines behind the scenes. Engines live in thermodynamics. Motors live in electromagnetism and fluid dynamics.

Etymology Meets Engineering: When History Guides Usage

I already covered the Latin roots, yet one more note helps. James Watt’s work on steam engines and the watt unit of power connect history to measurement. Rudolf Diesel gave his name to the diesel engine. Nikola Tesla contributed to AC motor technology and power systems. Karl Benz helped popularize the motor car. Those names pop up because they anchor our language. They also reinforce how engines and motors developed in parallel with different physics.

Edge Cases and Oddballs

What about tricky cases?

- Is a jet engine a motor? Technically it is an engine because it is a heat engine. People might say “jet motor” in casual speech, which is fine, yet “jet engine” is the precise term.

- Is a hydraulic motor an engine? No. It is a motor, not a heat engine.

- Can an electric motor be called an engine? In strict technical language, no. In casual language, people still do it sometimes.

- Are internal combustion engines motors? Yes. They are a type of motor in the broader sense because they convert energy into motion.

I also hear “diesel motor.” I take that as shorthand for a diesel engine. I do not fight it in conversation. I use “diesel engine” when I want to be precise.

Choosing the Right Term When You Write or Present

When I write a spec or explain a design to a mixed audience, I do this:

- I start with a one-line definition to set the frame.

- I use the precise term after that to avoid drift.

- I include one concrete example to lock the idea.

For example: “In this vehicle, the engine drives the generator and the electric motor drives the wheels.” One sentence shows both devices and their roles. No confusion.

A Peek Inside Electric Motors: The Hardware That Matters

You can ignore jargon and still appreciate why certain parts matter.

- Stator and rotor geometry influence torque density and efficiency.

- Laminated cores reduce losses at higher frequencies.

- Material selection balances saturation, loss, cost, and noise.

If you want a gentle materials tour, this quick guide to electrical steel laminations explains why laminations beat solid steel in motor cores. If you prefer a short visual on how the stationary and rotating parts share the work, this primer on the stator and rotor keeps it simple. For an intuitive feel of how current and magnetic fields create motion, the motor principle page connects the dots without heavy math. Finally, if you are curious about how manufacturers build the stationary core that guides the magnetic field, this overview of stator core lamination shows how stacked sheets set performance limits in many designs.

I repeat those links here because many readers ask for a light, non-mathy way to see the pieces. Pictures and simple diagrams stick better than a wall of text.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is a car engine a motor?

A: In everyday speech yes. In technical terms, the thing under the hood that burns gasoline or diesel is an internal combustion engine. It is a type of motor in the broad sense. If you want precision, call it an engine.

Q: Are electric motors engines?

A: No in technical language. Electric motors convert electrical energy to mechanical energy without combustion. Engines use combustion or heat. An engine is a type of motor. An electric motor is not a heat engine.

Q: What is a prime mover?

A: A prime mover is any device that converts energy into mechanical work to start motion in a system. Engines and motors both qualify.

Q: What is the difference between engine vs motor in one sentence?

A: Engines rely on combustion or heat while motors rely on electricity or fluid pressure.

Q: What powers a car today?

A: It depends on the drivetrain. A conventional car uses an internal combustion engine that burns gasoline or diesel. A hybrid has an engine and one or more electric motors. An electric vehicle uses one or more electric motors powered by a battery.

Q: Is a diesel engine a motor?

A: Yes in the broad sense. It is an internal combustion engine which makes it a type of motor. If you want precision, call it a diesel engine.

Q: Is a jet engine a motor?

A: It is a heat engine. We call it a jet engine in aerospace. Casual speech might say jet motor. Technical writing sticks with jet engine.

Q: Is a hydraulic motor an engine?

A: No. It is a motor that converts hydraulic pressure into rotation. No combustion occurs.

Q: What are common misconceptions about engines and motors?

A: Many people think a motor only means electric. Motor is the broader term. Others think engines and motors are complete synonyms, which blurs important differences in energy source and physics.

Q: Why do people say “motor” for a car?

A: History and habit. The early “motor car” phrase stuck. Mechanics also say “motor mounts” for internal combustion engines. Context and culture shaped the language.

Q: What is the core difference engine motor?

A: Engines are heat engines. Motors are broader devices that convert energy into motion, often using electricity or fluid pressure.

Q: What are typical parts of an engine vs a motor?

A: Engines have cylinders, pistons, valves, a crankshaft, and a fuel system. Electric motors have a stator, rotor, windings or magnets, and power electronics. Hydraulic and pneumatic motors have rotors or vanes and pressure seals.

Q: Which term is broader engine or motor?

A: Motor is broader. Engine is more specific.

Q: What units describe output for engines and motors?

A: Both use torque and power. Torque is measured in newton-meters or pound-feet. Power is measured in watts or horsepower.

Q: What is an electric prime mover?

A: It is a motor driven by electricity that acts as the primary source of mechanical power in a system.

Q: Does etymology matter in real life?

A: It helps when you want to understand why words overlap. It also helps you choose the right word when your audience expects precision.

Conclusion: Clear Terms for Clear Thinking

When I finally sorted out “engine vs motor,” I stopped tripping over words and started asking better questions. What energy source does this device use? What physical principles convert that energy into torque? Is it a heat engine or an electromagnetic or fluid-driven motor? Those questions lead to the right term without fuss. They also lead to smarter choices about fuels, batteries, hydraulics, emissions, controls, maintenance, and cost.

So is an engine a motor? An engine is a type of motor. Motors cover any device that turns energy into motion. Engines narrow that to devices that rely on combustion or heat. Use “engine” when you talk about gasoline, diesel, steam, and jets. Use “motor” when you talk about electric, hydraulic, and pneumatic drives. You will sound precise without sounding stuffy. More important, you will think clearly about how the machine in front of you really works.

Internal links used in this article: