Is Steel a Conductor of Electricity? Understanding Its Electrical Properties & Uses

Every engineer, designer, or fabricator has faced this question, often in a moment of critical decision-making. You might be designing a structural frame that will be near electrical equipment, specifying a material for an enclosure, or simply trying to assess a safety risk on a job site. The question seems simple, but the answer has layers of complexity that directly impact performance, safety, and cost.

So, let’s get straight to it.

Yes, steel is absolutely a conductor of electricity. However, the most important follow-up question is not if it conducts, but how well it conducts. This is where the true engineering challenge lies. Unlike copper or aluminum, which are prized for their exceptional ability to move electrons with minimal resistance, steel’s properties are far more nuanced. It’s a competent conductor but not an outstanding one, placing it in a unique category of materials whose conductivity is sometimes a feature to be leveraged and other times a challenge to be managed.

Understanding this distinction is key to making informed design choices. This guide will walk you through the fundamental science, the critical factors that change steel’s electrical behavior, and the real-world applications where its conductivity is either a hero or a hazard.

What We’ll Cover

- The Science Behind Steel’s Conductivity: A simple look at the physics of why metals conduct electricity.

- Key Factors That Influence Conductivity: How composition, temperature, and processing change the rules.

- A Guide to Different Types of Steel: Why stainless steel and carbon steel behave so differently.

- Steel vs. Other Materials: Putting steel’s performance in context against top-tier conductors and insulators.

- Practical Applications & Implications: Where steel’s conductivity is a benefit and where it’s a limitation.

- Critical Safety Considerations: How to work safely with a material that’s always “potentially live.”

The Science Behind Steel’s Electrical Conductivity

To understand why steel lets electricity flow, you don’t need a Ph.D. in material science. It all comes down to how its atoms are held together.

Metallic Bonding and the “Electron Sea”

Metals like steel are formed by what’s called a metallic bond. You can imagine it like this: picture a grid of positively charged metal ions (the steel atoms minus some electrons) sitting in a fixed structure. The electrons they’ve shed aren’t tied to any single atom; instead, they form a mobile “sea” of free electrons that flow around and among the ions.

It’s these delocalized, free-roaming electrons that are the heroes of electrical current. When you apply a voltage across a piece of steel, you’re essentially creating an electrical “pressure.” This pressure pushes the free electrons in the sea to move in a coordinated direction, and this flow of charge is what we call electrical current. Materials without this sea of free electrons, like plastic or glass, can’t support this flow and are therefore insulators.

Electrical Resistivity vs. Conductivity: Two Sides of the Same Coin

When we talk about how well a material conducts electricity, we use two related but opposite terms:

For any given material, if you know one value, you can find the other. The key takeaway is simple: Good conductors have high conductivity and low resistivity. Poor conductors (but not insulators) have low conductivity and high resistivity.

Steel falls somewhere in the middle of the metallic spectrum. It has a significant sea of free electrons, making it a conductor, but various factors create more “obstacles” for those electrons than you’d find in a material like copper.

Factors Influencing Steel’s Electrical Conductivity

Not all steel is created equal. The exact electrical resistivity of a steel alloy can vary dramatically based on three key factors: its recipe, its temperature, and how it was made.

1. Chemical Composition (Alloying Elements)

Pure iron is a reasonably good conductor. But steel isn’t pure iron; it’s an alloy, and the elements added to it have a profound effect on how electrons flow.

Think of the electron sea again. In pure iron, the atomic structure is fairly uniform, giving electrons a relatively clear path. Every alloying element you add acts like a disruption or an obstacle in that path, scattering the electrons and making it harder for them to flow smoothly.

- Carbon (C): As the carbon content in carbon steel increases, the electrical resistivity generally rises. The carbon atoms distort the iron crystal lattice, creating scattering points for electrons. This is why a high-carbon steel is a slightly poorer conductor than a low-carbon mild steel.

- Chromium (Cr) & Nickel (Ni): These are the magic ingredients that create stainless steel, but they are major disruptors of electron flow. They introduce significant disorder into the atomic lattice, which is why stainless steels have a much higher electrical resistivity (are poorer conductors) than plain carbon steels.

- Silicon (Si): Silicon is a fascinating case. It’s the key alloying element in electrical steel, which is used in applications like transformer lamination core and motor cores. Adding silicon significantly increases the steel’s resistivity. While this seems counterintuitive, it’s done intentionally to reduce energy losses from unwanted “eddy currents” in electromagnetic applications.

2. Temperature

For almost all metals, including steel, a simple rule applies: as temperature goes up, resistivity goes up.

Why? Imagine trying to walk through a quiet, still hallway. It’s easy. Now, imagine that same hallway is filled with people who are all randomly jumping and vibrating. It’s much harder to get through without bumping into someone.

The same thing happens at an atomic level. At higher temperatures, the metal ions in the crystal lattice vibrate more vigorously. This increased thermal vibration creates more “targets” for the flowing electrons to collide with, increasing resistance and reducing conductivity. This effect is why high-current electrical components need to be kept cool to operate efficiently.

3. Microstructure and Processing

How steel is physically formed and treated also impacts its electrical properties.

- Impurities and Defects: Any imperfection in the crystal lattice—whether it’s a stray impurity atom or a structural defect—can scatter electrons and increase resistivity.

- Cold Working vs. Annealing: Processes like rolling or drawing steel at room temperature (cold working) introduce a large number of dislocations and internal stresses. These act as electron-scattering centers, increasing resistivity. Conversely, annealing (heating the steel and cooling it slowly) relieves these stresses and repairs many defects, resulting in a more uniform structure with lower resistivity.

- Grain Structure: Steel is made of tiny crystals called grains. The boundaries between these grains can also impede electron flow. Generally, steels with larger grains tend to have slightly lower resistivity than fine-grained steels.

Electrical Conductivity of Different Types of Steel

With the influencing factors in mind, let’s look at how different families of steel perform in the real world. The differences are not trivial; they can be an order of magnitude apart.

Carbon Steel (e.g., Mild Steel)

This is the workhorse of the steel world. With relatively low amounts of alloying elements (mostly just iron and a small percentage of carbon), carbon steels are the most conductive of the common steel types. Because of their good conductivity combined with strength and low cost, they are frequently used for applications where electrical continuity is important, such as structural grounding and electrical enclosures.

- Typical Resistivity (1010 Mild Steel): ~15 x 10⁻⁸ Ω·m

- Typical Conductivity: ~6.5 x 10⁶ S/m

Stainless Steel

Stainless steel is famous for its corrosion resistance, thanks to a high chromium content (and often nickel). As we discussed, these alloying elements make it a significantly poorer conductor than carbon steel.

- Austenitic Stainless (e.g., 304, 316): These are the most common types. The high concentration of chromium and nickel gives them the highest resistivity among steels—sometimes 40-50 times higher than copper.

- Ferritic Stainless (e.g., 430): With chromium but no nickel, these are slightly better conductors than austenitic grades but still far more resistive than carbon steel.

The poor conductivity of stainless steel is actually a benefit in some applications. For example, it reduces the risk of creating unintended electrical pathways in certain corrosive environments.

- Typical Resistivity (304 Stainless): ~72 x 10⁻⁸ Ω·m

- Typical Conductivity: ~1.4 x 10⁶ S/m

Electrical Steel (Silicon Steel)

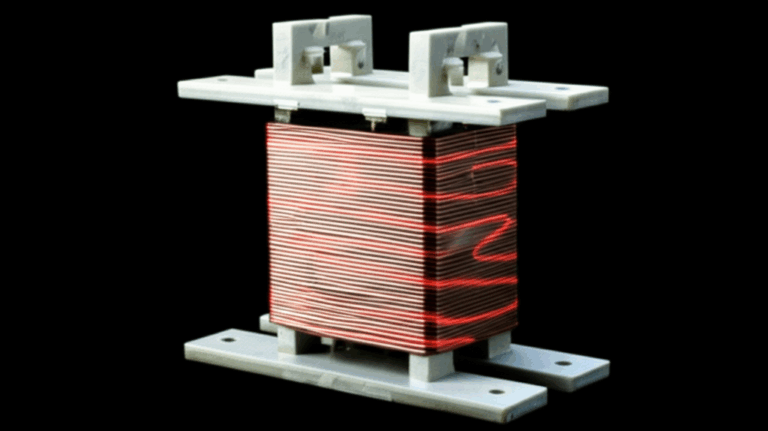

This is a specialty product engineered for the heart of our electrical world: motors, generators, and transformers. As mentioned, silicon is added to iron to deliberately increase its electrical resistivity. This is crucial for minimizing eddy current losses. When a magnetic core is exposed to a changing magnetic field (like in a transformer), small, circular eddy currents are induced in the material. These currents do no useful work; they only generate heat, which is wasted energy.

By making the steel more resistive and by constructing cores from thin, insulated sheets known as electrical steel laminations, engineers can significantly suppress these wasteful currents and dramatically improve the efficiency of the device.

Steel’s Conductivity in Comparison to Other Common Materials

To truly appreciate steel’s electrical properties, it helps to see where it stands in the grand scheme of materials.

| Material | Type/Grade | Electrical Resistivity (ρ) at 20°C (10⁻⁸ Ω·m) | Notes / Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent Conductors | |||

| Copper | Pure | 1.68 | The industry benchmark. Steel has roughly 10 times the resistivity. |

| Aluminum | Pure | 2.82 | Lighter than copper and used for power lines. Steel is ~5-6 times more resistive. |

| Steels | |||

| Carbon Steel | 1010 (Low Carbon) | ~15 | The best conductor among common steels, but still no match for copper. |

| Electrical Steel | M-19 (Silicon Steel) | ~47 | Resistivity is intentionally high to reduce energy loss in magnetic cores. |

| Stainless Steel | 304 (Austenitic) | ~72 | A very poor conductor for a metal, with over 40 times the resistivity of copper. |

| Insulators | |||

| PVC | >10¹⁴ | In a completely different league. The resistivity is trillions of times higher than steel. |

This comparison makes one thing crystal clear: you would never use steel for electrical wiring. The high resistivity would cause an unacceptable amount of energy to be lost as heat (a phenomenon known as I²R loss), leading to massive inefficiency and a serious fire hazard. This is precisely why copper and aluminum dominate the world of electrical conductors.

Practical Applications and Implications of Steel’s Conductivity

Steel’s unique position as a structural material that also conducts electricity means its properties are used—and managed—in countless ways.

Where Steel’s Conductivity is Beneficial

Where Steel’s Conductivity is a Limitation or Requires Caution

Safety Considerations When Working with Steel and Electricity

The single most important rule is to always assume any steel structure is potentially conductive and live. Never make assumptions.

- Verify De-energization: Before working on or near electrical systems, always use a proper tester to verify that circuits are off. Lock out and tag out power sources to prevent accidental re-energization.

- Use Proper PPE: When working around potential electrical hazards, use appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), including insulated gloves, tools, and footwear.

- Understand Grounding: Ensure all metallic systems, including structural steel, conduit, and enclosures, are properly bonded and grounded according to local electrical codes. A proper ground is your primary defense against electric shock.

Conclusion: Key Takeaways on Steel’s Electrical Properties

Let’s circle back to our original question. Is steel a conductor? The answer is a definitive yes, but its story is one of nuance.

- Steel is a Conductor, Not a Connector: It allows electricity to flow but with significantly more resistance than copper or aluminum. This makes it unsuitable for efficient power transmission like wiring.

- Its Properties Are Deliberately Engineered: The conductivity of steel isn’t a one-size-fits-all property. It varies widely depending on the alloy—from the relatively good conductivity of carbon steel to the poor conductivity of stainless steel and the intentionally high resistivity of electrical steel.

- A Material of Duality: Steel’s conductivity is a vital safety feature in applications like grounding and enclosures, while simultaneously being a source of energy loss (eddy currents) that must be engineered around in motors and transformers.

By understanding these properties, you can move beyond a simple “yes” or “no.” You can leverage steel’s strength and conductivity where it benefits your design and mitigate its effects where it poses a challenge. This knowledge empowers you to build systems that are not only functional but also safe, efficient, and reliable.