Is Steel a Conductor or Insulator of Electricity? Understanding Its Electrical Properties

Every engineer, designer, and fabricator eventually confronts a fundamental question about the materials they use: how does this behave around electricity? When it comes to one of the world’s most versatile and ubiquitous materials, the question is clear: is steel a conductor or an insulator of electricity? If you’ve found yourself needing a definitive answer for a project, a safety assessment, or just to satisfy your own curiosity, you’re in the right place.

The short, unambiguous answer is: Steel is an electrical conductor.

An electrical current will always pass through it when given the chance. However, this simple fact is just the beginning of the story. Unlike a simple on-or-off switch, steel’s conductivity isn’t a single, static property. It’s a complex characteristic that varies significantly based on the steel’s specific alloy, its temperature, and even its condition. Understanding these nuances is critical for using steel safely and effectively in any electrical or structural application.

This guide will break down the engineering principles behind steel’s conductivity. We’ll explore why it conducts, how different types of steel compare, and where its conductive properties are both a vital asset and a potential hazard.

What We’ll Cover

- What Makes Steel a Conductor? The science behind its atomic structure.

- Steel’s Electrical Conductivity: A Closer Look. Exploring the factors that change how well steel conducts.

- Types of Steel and Their Electrical Properties. A comparison of common alloys like carbon and stainless steel.

- Steel as an “Insulator”? Addressing the Misconception. Clarifying why steel is never a true insulator.

- Practical Applications and Implications. Where steel’s conductivity is used to our advantage.

- Comparison: Steel vs. Other Materials. Putting steel’s properties in context with true conductors and insulators.

What Makes Steel a Conductor?

To understand why steel allows electricity to flow, we need to zoom in to the atomic level. The answer lies in the way its atoms bond together and the behavior of its electrons. It’s less like a series of individual components and more like a collective community.

A. Metallic Bonding and Free Electrons

Metals, including steel’s primary component iron, are defined by a unique type of chemical bond called a metallic bond. Imagine a tightly packed grid of metal atoms. Each atom contributes one or more of its outermost electrons to a shared “sea” of electrons that are no longer tied to any single atom.

These delocalized or “free electrons” are the key to conductivity. They aren’t locked in place but are free to drift throughout the entire metal structure.

Think of it like this: an insulator like rubber is like a parking garage where every car (electron) is assigned to a specific, unchangeable spot. The cars can’t move so no flow is possible. A metal conductor, on the other hand, is like a massive, open parking lot where the cars (electrons) can drive anywhere they want. When you apply a voltage (an electrical “pressure”) across the metal, you create a gentle but consistent push on this sea of electrons causing them to flow in one direction. This directed flow of electrons is what we call an electrical current.

B. Atomic Structure of Steel

Steel isn’t a pure element but an alloy—a material made by mixing a base metal with other elements to enhance its properties. The base metal in steel is iron (Fe), which on its own is a good conductor because of its metallic bonds and free electrons.

The most common alloying element in steel is carbon (C). While carbon itself can be a conductor (like graphite) or an insulator (like diamond), its role in steel is primarily structural. The carbon atoms wedge themselves into the iron crystal lattice making it stronger and harder. However, these additions also disrupt the perfectly ordered structure of the iron atoms.

This disruption acts as a tiny obstacle course for the flowing electrons. As electrons move through the material, they collide with these imperfections and the atoms of other alloying elements. Each collision slows the electron down and converts some of its kinetic energy into heat. This opposition to the flow of current is known as electrical resistance.

Therefore, while all steel conducts electricity because its iron base has a sea of free electrons, the specific amount of resistance it has depends heavily on what other elements are mixed in.

Steel’s Electrical Conductivity: A Closer Look

Now that we know steel is a conductor, the more practical engineering question becomes: how good of a conductor is it? To answer that, we need to look at two key properties: conductivity and resistivity. They are two sides of the same coin.

A. Conductivity vs. Resistivity

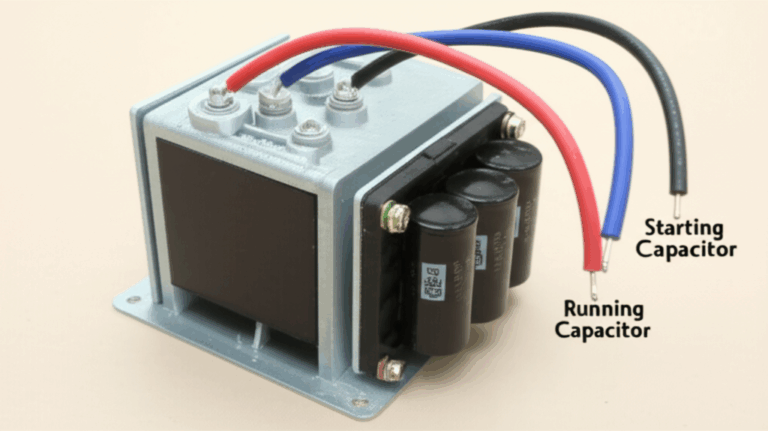

- Electrical Conductivity measures how easily an electrical current can flow through a material. It’s like measuring the width of a pipe—a wider pipe allows more water to flow with less effort. The standard unit for conductivity is Siemens per meter (S/m). A higher Siemens value means a better conductor.

- Electrical Resistivity is the inverse. It measures how much a material opposes the flow of electrical current. It’s like the friction or gunk inside the pipe that slows the water down. The standard unit for resistivity is the Ohm-meter (Ω·m). A higher Ohm-meter value means the material is a poorer conductor (and a better resistor).

For any given material, if you know one value you can calculate the other. In engineering, resistivity is often more commonly cited when comparing metals because it directly relates to energy loss and heat generation via Ohm’s Law.

B. Factors Influencing Steel’s Conductivity

The exact resistivity of steel isn’t a single number. It varies based on several critical factors that a designer or engineer must consider.

- Alloying Elements: This is the biggest factor. Pure iron is a decent conductor but as we add more elements to create different steel alloys, the resistivity almost always increases.

- Carbon (C): Even the small amounts in plain carbon steel increase resistivity compared to pure iron.

- Chromium (Cr) and Nickel (Ni): These are the key ingredients in stainless steel. They are fantastic for preventing corrosion but they significantly disrupt the iron lattice, causing a dramatic increase in electrical resistivity. This is why stainless steel is a much poorer conductor than plain carbon steel.

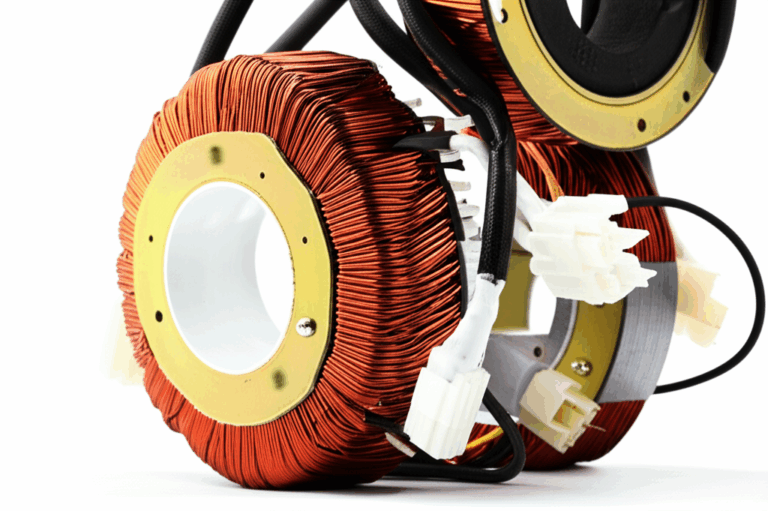

- Manganese (Mn), Molybdenum (Mo), and Silicon (Si): These and other common alloying elements also contribute to increased resistivity. The more “stuff” you add to the iron, the more obstacles you create for the flowing electrons. Many components designed for electrical machinery, such as the stator and rotor, are made from specialized steel alloys to control these properties.

- Temperature: For nearly all metals, including steel, an increase in temperature causes an increase in resistivity. As the material heats up, its atoms vibrate more vigorously. This creates more “traffic” and makes it harder for the free electrons to find a clear path, leading to more collisions and higher resistance. This is a crucial consideration in high-current applications where heat buildup can further increase resistance in a feedback loop.

- Impurities and Microstructure: Beyond intentional alloys, any unintended impurities in the steel can also increase resistivity. The way the steel is processed—whether it’s been hardened, tempered, or annealed—changes its internal crystal structure (microstructure) and can have a measurable effect on its electrical properties.

- Corrosion/Oxidation: Rust (iron oxide) is a poor electrical conductor. A heavily rusted piece of steel may have high surface resistance, even though the uncorroded metal underneath is still conductive. For electrical connections that rely on steel, such as grounding clamps, it’s vital to ensure a clean, rust-free contact point to minimize resistance and ensure a reliable path for the current. This oxidation effect is a key reason why steel isn’t used for direct wiring.

Types of Steel and Their Electrical Properties

The term “steel” covers a massive family of alloys each with a unique recipe and distinct properties. When it comes to electrical performance, the differences can be substantial.

A. Carbon Steel

Carbon steel, which includes common varieties like mild steel and structural steel, is defined by its relatively simple composition: primarily iron and a small amount of carbon (typically less than 2%). Because it has fewer alloying elements to obstruct electron flow, carbon steel is the most conductive type of common steel.

Its resistivity is typically in the range of 1.4 to 1.7 x 10⁻⁷ Ω·m. While this is still about 8-10 times more resistive than pure copper, its combination of strength, low cost, and decent conductivity makes it an excellent choice for applications where it won’t be carrying current continuously over long distances.

B. Stainless Steel

Stainless steel is famous for its exceptional corrosion resistance, which it gets from a high chromium content (usually a minimum of 10.5%). Many common grades, like 304 and 316, also contain significant amounts of nickel.

As discussed, these alloying elements dramatically increase electrical resistivity. The resistivity of 304 stainless steel is around 6.9 x 10⁻⁷ Ω·m—roughly 4 to 5 times more resistive than plain carbon steel. This makes stainless steel a relatively poor conductor. While it will absolutely conduct electricity and can still cause a dangerous shock, it’s not suitable for applications where efficient current flow is the primary goal. Its value lies where you need both structural integrity and corrosion resistance in an environment that may have electrical potential.

C. Other Steel Alloys

The world of steel includes countless other alloys, from ultra-hard tool steels to tough alloy steels used in machine parts. Generally, the rule holds true: the more complex the alloy, the higher the electrical resistivity. Specialized materials like electrical steel (also known as silicon steel) are engineered with specific magnetic properties and controlled electrical resistivity, making them essential for building efficient motor core laminations and transformers.

Steel as an “Insulator”? Addressing the Misconception

Given that some steels are relatively poor conductors, it’s easy to see how a common misconception arises: can steel sometimes act as an insulator?

A. No, Steel is Never a True Insulator

Let’s be perfectly clear: steel is never an electrical insulator. An insulator is a material that has virtually no free electrons and possesses an extremely high resistivity, making it nearly impossible for current to flow. Materials like glass, rubber, plastic, and ceramics are true insulators. Their resistivity is trillions of times higher than even the most resistive stainless steel.

You can safely grab a plastic-coated wire because the plastic insulator prevents the electricity from reaching you. If you grab a bare steel rod that is energized, the current will flow through it—and through you—to the ground.

B. Misinterpretations

The confusion usually stems from two areas:

Practical Applications and Implications

Understanding steel’s conductive nature is essential for its safe and effective use in countless applications. We leverage its properties for much more than just building bridges.

A. Where Steel is Used as a Conductor

In many cases, steel’s combination of strength, durability, and moderate conductivity is exactly what’s needed.

- Structural Grounding/Earthing: This is one of steel’s most important electrical roles. The steel rebar (reinforcing bar) in a concrete foundation and the steel frame of a skyscraper create a massive, effective path to the earth. This grounding electrode system is vital for safety, providing a path for lightning strikes or fault currents to dissipate harmlessly into the ground.

- Electrical Conduits: Steel conduits are pipes used to protect electrical wiring. Not only do they provide physical protection but their conductivity serves a crucial safety function. If a live wire inside accidentally touches the conduit, the steel provides a low-resistance path that will immediately trip a circuit breaker, preventing the conduit from becoming an electrocution hazard.

- Electromagnetic Shielding: The conductive and magnetic properties of steel make it excellent for creating enclosures that block electromagnetic interference (EMI). Steel boxes shield sensitive electronics from outside “noise” and prevent a device’s own emissions from interfering with other equipment.

- Switchgear & Electrical Enclosures: The housings for circuit breakers, panels, and other electrical equipment are almost always made of steel. It provides the necessary strength and fire resistance, and its conductive nature allows the entire enclosure to be easily and effectively grounded for safety.

B. Why Steel is Not Used for Direct Wiring

If steel conducts electricity, why don’t we use it to wire our homes and buildings?

- Higher Resistivity: As mentioned, steel’s resistivity is many times higher than copper’s. Pushing current through a more resistive material generates more heat and wastes more energy. Using steel for wiring would lead to significant energy loss and potentially create a fire hazard due to overheating.

- Corrosion: Most carbon steels rust easily. A corroded electrical connection becomes highly resistive and unreliable, leading to failures and potential arcing.

- Weight and Flexibility: For a given current-carrying capacity, a steel wire would need to be much thicker and heavier than a copper or aluminum one, making it impractical and difficult to install. Copper’s ductility is a major advantage in wiring.

C. Safety Considerations

The most important takeaway is a simple one: Always assume any steel component is conductive. Whether it’s a structural beam, a metal ladder, a fence post, or a tool, treat it as a potential path for electricity if it comes into contact with a live source. Proper grounding of steel structures and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) like insulated gloves are non-negotiable safety practices when working near electricity.

Comparison: Steel vs. Other Materials

To fully appreciate steel’s electrical properties, it helps to see where it stands on the conductivity spectrum. The differences between material classes are not just small—they are astronomically large.

The table below provides a clear comparison of the electrical properties of steel against some of the best conductors, common insulators, and semiconductors.

Table: Electrical Conductivity and Resistivity of Common Materials (20°C / 68°F)

| Material Type | Specific Material | Electrical Conductivity (S/m) | Electrical Resistivity (Ω·m) | Notes / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent Conductors | Silver (Pure) | ~6.30 x 10⁷ | ~1.59 x 10⁻⁸ | Best electrical conductor; high cost limits widespread use. |

| Copper (Pure) | ~5.96 x 10⁷ | ~1.68 x 10⁻⁸ | Standard for electrical wiring, cables, and busbars due to cost, conductivity, and ductility. | |

| Aluminum (Pure) | ~3.77 x 10⁷ | ~2.65 x 10⁻⁸ | Lighter and cheaper than copper; used in power transmission lines. | |

| Steel (Conductors) | Carbon Steel (e.g., 1018) | ~5.9-7.0 x 10⁶ | ~1.4-1.7 x 10⁻⁷ | Good conductor among steels. Used in structural grounding, conduits, enclosures. |

| Stainless Steel (e.g., 304) | ~1.45 x 10⁶ | ~6.9 x 10⁻⁷ | Lower conductivity than carbon steel due to alloying. Used where corrosion resistance is key. | |

| Semiconductors | Silicon (Pure) | ~1.0 x 10⁻³ to 1.0 x 10⁴ | ~1.0 x 10⁻⁴ to 1.0 x 10³ | Conducts under specific conditions; basis for transistors and microchips. |

| Insulators | Glass | ~1.0 x 10⁻¹⁰ to 1.0 x 10⁻¹⁵ | ~1.0 x 10¹⁰ to 1.0 x 10¹⁵ | Used in electrical components, windows. |

| Wood (Dry) | ~1.0 x 10⁻¹⁴ to 1.0 x 10⁻¹⁶ | ~1.0 x 10¹⁴ to 1.0 x 10¹⁶ | Insulator but conductivity increases significantly with moisture. | |

| Rubber (Hard) | ~1.0 x 10⁻¹⁵ | ~1.0 x 10¹⁵ | Used for electrical insulation (wire coatings, gloves). |

A. Vs. Excellent Conductors

When you look at the numbers, the difference is stark. Copper is about 10 times more conductive than carbon steel. This is why it remains the gold standard for wiring; it moves electricity with maximum efficiency and minimum heat loss. While silver is technically the best conductor, its cost makes it impractical for anything but specialty applications. Aluminum, though less conductive than copper, is used for high-voltage power lines because its lighter weight is a major advantage.

B. Vs. Insulators

The gap between steel and an insulator like rubber is almost incomprehensibly vast. Rubber’s resistivity is a quadrillion (a one followed by 15 zeros) times higher than steel’s. This is why even a thin layer of rubber or plastic insulation can safely contain thousands of volts while a thick steel bar cannot. There is simply no comparison; they are fundamentally different classes of material. Even materials we make advanced components out of, such as a transformer lamination core, rely on thin insulating coatings between each layer to function properly.

C. Vs. Semiconductors

Semiconductors like silicon occupy a fascinating middle ground. Their conductivity can be precisely controlled by adding impurities (a process called doping) or by applying an electric field. This ability to switch their conductive state on and off is the foundation of all modern electronics, from transistors to microchips. Steel, as a conductor, cannot be “switched off” in this way.

Conclusion

So, is steel a conductor or an insulator? The answer is definitively a conductor. Its metallic structure, inherited from its primary component iron, provides a sea of free electrons that allows electrical current to flow through it.

However, that’s just the starting point. The key engineering takeaway is that steel is a variable and moderately resistive conductor.

- Steel is a Conductor, Never an Insulator: This is the most critical safety principle. Always treat steel as electrically live in hazardous environments.

- Alloys Determine Performance: The specific type of steel dictates its electrical performance. Plain carbon steel is a reasonably good conductor, while highly alloyed stainless steel is a significantly poorer one.

- A Tool for the Right Job: Steel’s high resistance makes it unsuitable for efficient power transmission like house wiring.

- Essential for Infrastructure and Safety: Its unique combination of strength, low cost, and conductivity makes it indispensable for structural grounding, electrical conduits, and shielding enclosures.

By understanding these principles, you can make more informed decisions in your designs, ensure a safer work environment, and leverage the incredible properties of steel—not just for its strength but for its essential role in our electrical world.