Is Steel an Electrical Conductor? A Complete Guide for Engineers

As an engineer or designer, you’re constantly making critical decisions about materials. You weigh strength, cost, durability, and a dozen other factors. When it comes to electrical applications, one question often arises: “Is steel an electrical conductor?” It seems simple, but the answer has significant implications for everything from structural safety to component design.

The short answer is a definitive yes, steel is an electrical conductor.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The real question isn’t if it conducts, but how well it conducts, what factors change its performance, and where its unique properties make it the perfect choice—or a terrible one. If you’ve ever found yourself evaluating steel for grounding, enclosures, or structural components in an electrical system, you’re in the right place. This guide breaks down the science, the practical applications, and the critical trade-offs you need to understand.

What We’ll Cover

- The Science Behind Steel’s Electrical Conductivity: Why it works.

- Steel’s Conductivity: How Does It Stack Up?: A comparison with other metals.

- Factors That Change How Well Steel Conducts Electricity: The crucial details.

- Where Steel Shines: Practical Applications as a Conductor: Its best-fit uses.

- The Other Side of the Coin: Limitations of Steel as a Conductor: When to avoid it.

- Safety First: Working with Steel in Electrical Systems: Non-negotiable practices.

- Your Engineering Takeaway: Key Points to Remember: The final summary.

The Science Behind Steel’s Electrical Conductivity

To understand why steel conducts electricity, we need to look at its atomic structure. Like other metals, steel’s properties are defined by a concept called metallic bonding.

Imagine a tightly packed grid of steel atoms. Each atom contributes one or more of its outermost electrons to a shared “sea” of electrons that are not bound to any single atom. These are called free electrons. They’re untethered and can move freely throughout the metal’s crystalline structure.

When you apply a voltage across a piece of steel, you create an electrical field. This field acts like a current in a river, pushing the free electrons to flow in a coordinated direction from a negative potential to a positive one. This flow of charge carriers is what we call electrical current.

Conductivity vs. Resistivity: Two Sides of the Same Coin

To quantify this property, we use two key measurements:

Every material has some level of both. Excellent conductors have high conductivity and very low resistivity. Insulators, like rubber or glass, have incredibly low conductivity and astronomical resistivity because they lack that sea of free electrons. Steel sits squarely in the conductor category, but as we’ll see, its resistivity is significantly higher than that of copper or aluminum.

Steel’s Conductivity: How Does It Stack Up?

Knowing steel conducts isn’t enough; you need to know where it stands in the league of metals. Context is everything for a design engineer.

Steel vs. Top Conductors: Copper, Aluminum & Silver

When it comes to pure electrical efficiency, steel can’t compete with the top contenders. Let’s look at the numbers.

| Material Type | Electrical Resistivity (µΩ·cm at 20°C) | Electrical Conductivity (MS/m at 20°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Pure Silver | 1.59 | 63.0 |

| Pure Copper | 1.68 | 59.6 |

| Pure Aluminum | 2.65 | 37.8 |

| Mild Steel (Carbon) | 10-20 | 5-10 |

| Stainless Steel (304) | ~72 | ~1.39 |

MS/m = Megasiemens per meter

As you can see, mild carbon steel’s resistivity is roughly 6 to 12 times higher than copper’s. This means for the same-sized wire, steel will generate far more heat and suffer a greater voltage drop when carrying the same amount of current. This is precisely why we don’t use steel for building wiring or motor windings. The energy loss (I²R loss) would be unacceptably high.

Stainless steel is an even poorer conductor, with a resistivity over 40 times that of copper. The chromium, nickel, and other alloying elements that give stainless its incredible corrosion resistance also disrupt the crystal lattice, making it much harder for electrons to flow freely.

Steel vs. Insulators

This one isn’t even a fair fight. Materials like rubber have a resistivity on the order of 10¹⁵ µΩ·cm. That’s a quadrillion times more resistive than steel. This massive difference is why we can safely use steel structures to support live electrical conductors, as long as those conductors are properly insulated. The current will always follow the path of least resistance, which is the highly conductive copper wire, not the steel support beam.

Factors That Change How Well Steel Conducts Electricity

Here’s where things get interesting for engineers. “Steel” isn’t one material; it’s a vast family of alloys, and its electrical properties can change dramatically based on several factors.

1. Composition and Alloying Elements

The single biggest factor is what’s in the steel. Steel is fundamentally an alloy of iron and carbon, but other elements change its properties.

- Carbon Content: Generally, higher carbon content slightly increases electrical resistivity. The carbon atoms distort the iron crystal lattice, creating more “obstacles” for the free electrons to navigate. This is why low-carbon mild steel is a better conductor than high-carbon tool steel.

- Alloying Elements (Chromium, Nickel, Manganese, Silicon): This is the main reason for the huge difference between carbon steel and stainless steel. Elements like chromium and nickel are added to provide corrosion resistance and strength, but they are highly effective at scattering electrons. This scattering dramatically increases resistivity. For applications where conductivity is desired, using a plain carbon steel is far better than a stainless alloy. Specialized electrical steel laminations often include silicon to control magnetic properties, which also affects resistivity.

2. Temperature

For most metals, including steel, electrical resistance increases as temperature rises. When the steel heats up, its atoms vibrate more intensely. These vibrations cause more frequent collisions with the flowing electrons, impeding their path and increasing resistivity. This is described by the material’s resistivity temperature coefficient. It’s a critical consideration in applications where a steel component might heat up under load, as its resistance won’t be constant.

3. Corrosion and Surface Oxidation

This is steel’s Achilles’ heel in electrical applications. Iron oxide, or rust, is a very poor electrical conductor—it’s more of an insulator. A thick layer of rust on a grounding connection or between structural steel components can dramatically increase the resistance of the electrical path.

Case Study: Rebar in Concrete

A study on steel reinforcing bars (rebar) in concrete found that localized corrosion can increase the electrical resistivity of the rebar by several orders of magnitude. This can render cathodic protection systems ineffective and compromise the integrity of a structure’s grounding grid, which often relies on the continuity of the rebar cage.

This is why galvanized steel is often used. The zinc coating provides sacrificial corrosion protection. While zinc has a different resistivity than steel, its primary electrical benefit is preventing the formation of that insulating rust layer, ensuring a reliable conductive path over the long term.

4. Impurities and Structural Defects

Even minuscule impurities or defects in the steel’s crystal structure, like grain boundaries or dislocations, can scatter electrons and increase resistivity. While this is more of a concern at the material science level, it explains why purer metals are almost always better conductors. The heat treatment and work-hardening processes a steel component undergoes can also alter its grain structure and, consequently, its conductivity.

Where Steel Shines: Practical Applications as a Conductor

If steel is a relatively poor conductor compared to copper, why do we use it in electrical systems at all? Because it has two massive advantages: strength and cost. In many applications, these benefits far outweigh its lower conductivity.

1. Grounding Systems

Steel is a workhorse in electrical grounding.

- Grounding Rods: While pure copper rods exist, the most common type is a copper-clad steel rod. The steel core provides the immense strength needed to drive the rod deep into hard soil without bending. The copper cladding provides a corrosion-resistant, highly conductive interface with the earth.

- Structural Grounding: The steel frame of a building or a large industrial facility is often used as a key part of the grounding electrode system. According to the National Electrical Code (NEC), this is a legitimate and effective way to provide a path to earth for fault currents and lightning strikes, provided all connections are properly bonded.

2. Electrical Conduit and Enclosures

Steel conduit (EMT, IMC, and RMC) is used everywhere to protect electrical wiring. Its primary job is physical protection, but it serves a critical secondary electrical function. When installed correctly, the steel conduit itself acts as an equipment grounding conductor, providing a safe path for a fault current to travel back to the breaker panel and trip the circuit. The same goes for steel electrical boxes and enclosures.

3. Structural Elements with Secondary Conduction Roles

Many large-scale systems use steel’s conductive properties out of necessity and convenience.

- Railway Tracks: In electrified rail systems, the overhead lines deliver the power, but the steel tracks themselves often serve as the return path for the traction current. They are also essential for track circuit signaling systems that detect the presence of a train.

- Transmission Towers: The massive steel lattice towers that support high-voltage power lines aren’t there to carry the primary current. However, they are a crucial part of the lightning protection system. The overhead ground wire (the very top wire) is designed to intercept lightning strikes and safely conduct the massive current down through the steel tower and into the earth.

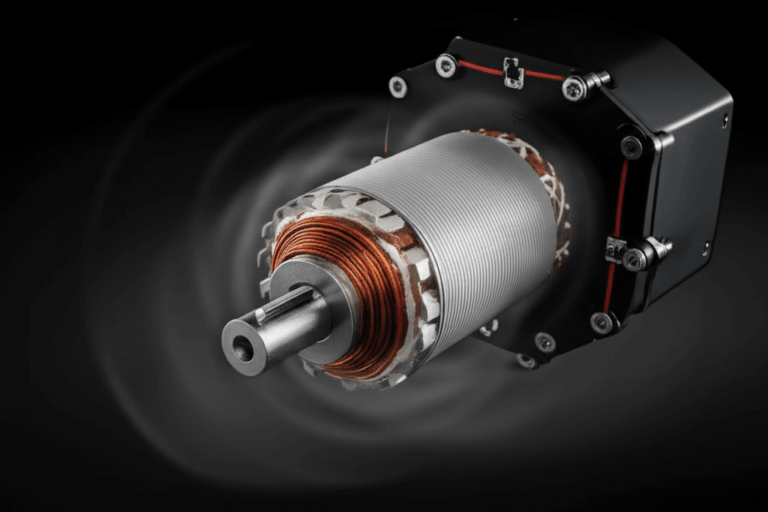

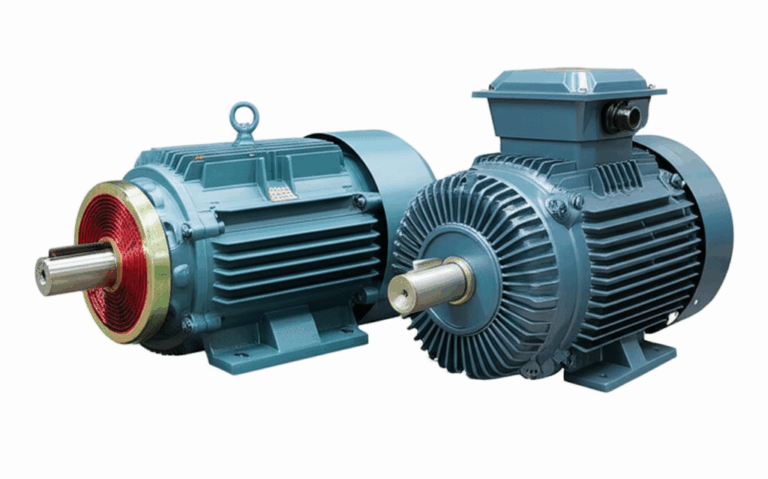

- Components in Motors and Generators: In the world of electric machines, steel is indispensable. The magnetic core, composed of the stator and rotor, is made from specialized steel alloys. While we want to limit electrical currents within the core itself (eddy currents), the entire steel structure provides a path to ground for safety.

4. EMI/RFI Shielding

Steel’s magnetic properties (specifically, its high magnetic permeability) make it an excellent material for shielding sensitive electronics from electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio-frequency interference (RFI). A steel enclosure can absorb and redirect stray magnetic fields, protecting the components inside.

The Other Side of the Coin: Limitations of Steel as a Conductor

Understanding steel’s weaknesses is just as important as knowing its strengths.

1. Higher Resistivity and Energy Loss

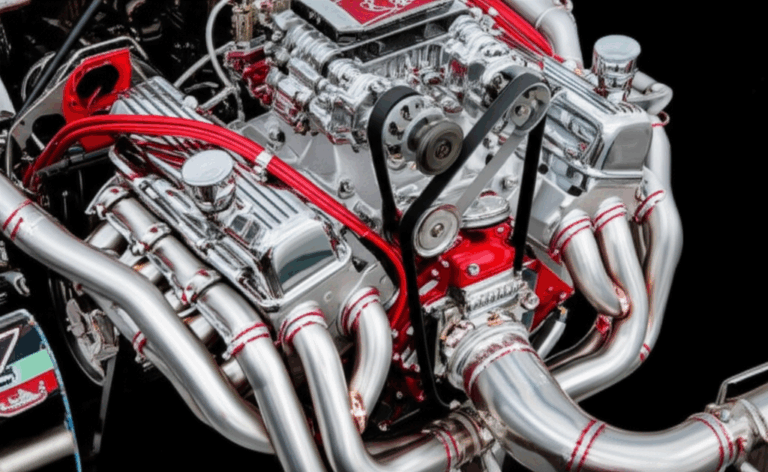

As discussed, steel’s higher resistivity means more energy is converted to waste heat for a given current. This makes it unsuitable for efficient power transmission. Using steel for a long-distance power line instead of aluminum or copper would result in massive energy losses and a significant voltage drop at the destination. Any such issue can be considered a serious motor problem when it comes to efficiency.

2. Magnetic Properties in AC Circuits

This is a huge consideration for engineers. Steel is a ferromagnetic material. When used in an alternating current (AC) circuit, its magnetic properties can cause two major problems:

- Eddy Currents: The changing magnetic field from the AC current induces small, circulating currents within the steel conductor itself. These “eddy currents” do no useful work and only generate heat, representing a significant energy loss. This is the very reason a transformer lamination core is built from thin, insulated sheets of steel—to break up and minimize these wasteful currents.

- Hysteresis Loss: Every time the AC cycle reverses, energy is spent to flip the magnetic domains within the steel. This energy is lost as heat and is known as hysteresis loss.

These losses are why solid steel conduits can get hot when carrying large AC currents and why they are generally avoided for single-conductor, high-current applications unless specific precautions are taken.

3. Weight

For applications like overhead power lines, weight is a primary concern. Aluminum is the material of choice not just for its good conductivity but also because it has a much better conductivity-to-weight ratio than steel or even copper. Lighter wires mean fewer support towers are needed, drastically reducing construction costs.

Safety First: Working with Steel in Electrical Systems

Because steel is a conductor, treating it with respect in any electrical environment is paramount.

- Assume It’s Live: Always assume any steel structure, conduit, or enclosure near electrical equipment could become energized during a fault condition. Never touch it without proper personal protective equipment (PPE) if there’s a risk of an electrical fault.

- Proper Grounding and Bonding: This is non-negotiable. All steel components in an electrical system must be properly bonded together and connected to the main grounding system. This ensures that if a live wire accidentally touches a steel conduit or frame, the fault current has a low-resistance path back to the source, which will trip the breaker or blow the fuse instantly. A poorly bonded connection creates a dangerous shock hazard.

- Insulation is Key: The safety of systems using steel structures relies on the integrity of the primary conductor’s insulation. A frayed or damaged wire can energize an entire steel frame, creating an incredibly dangerous situation.

Your Engineering Takeaway: Key Points to Remember

So, is steel an electrical conductor? Yes, absolutely. But its role is nuanced and specific.

Here’s the final breakdown for your next design review:

- Steel Is a Conductor, Not a Primary Wire: It conducts electricity, but its resistivity is too high for efficient power transmission. Leave that job to copper and aluminum.

- Strength and Cost Are Its Superpowers: Steel is the ideal choice when you need mechanical strength and conductivity is a secondary but necessary function (e.g., grounding rods, conduits, structural grounding).

- The Alloy Matters—Immensely: Plain low-carbon steel is a decent conductor. Stainless steel is a poor conductor. Always check the specific grade of steel you’re using.

- Watch Out for Corrosion and AC: Rust can destroy a reliable electrical connection. In AC systems, steel’s magnetic properties can cause significant energy losses and heating if not properly managed.

Ultimately, steel is a versatile and indispensable material in the electrical world. By understanding its properties—both the good and the bad—you can leverage its strength and cost-effectiveness to build safe, reliable, and efficient systems.