Is the Ford 5.4 Triton a Good Motor? A Comprehensive Assessment

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Ford 5.4L Triton V8 – A Legacy of Power and Controversy

- Generations of the 5.4L Triton: 2-Valve vs. 3-Valve Engines

- The 2-Valve 5.4L Triton (1997–2004): Simpler Design, Fewer Systemic Flaws

- The 3-Valve 5.4L Triton (2004–2010+, some models to 2014): Enhanced Performance, Increased Complexity

- The Notorious 5.4L Triton Problems: What to Expect

- Cam Phasers and VCT System Failure (3-Valve Specific)

- Spark Plug Breakage and Ejection

- Timing Chain and Guide Wear (Mostly 3-Valve)

- Low Oil Pressure and Sludge Buildup

- Exhaust Manifold Studs and Ticking

- A Few Other Issues I Watch For

- Strengths and Advantages of the 5.4L Triton

- Performance and Fuel Economy Overview

- Is the 5.4 Triton a Good Motor for You? Buying and Ownership Considerations

- Crucial Pre-Purchase Inspection Points

- Model Years to Prioritize or Avoid

- The Importance of Maintenance Records

- Budgeting for Potential Repairs

- Maximizing Your 5.4L Triton’s Lifespan: Essential Maintenance Tips

- Quick Comparisons: 5.4 Triton vs 5.0 Coyote vs 6.2L V8

- Conclusion: A Nuanced Verdict on the 5.4L Triton

Introduction: The Ford 5.4L Triton V8 – A Legacy of Power and Controversy

I’ve bought, driven, inspected, and helped friends wrench on trucks and SUVs with the 5.4L Triton for years. You see this engine everywhere. Ford put it in F-150s, Expeditions, E-Series vans, Navigators, and Super Duty models. It’s the workhorse that built a reputation for solid torque and big towing numbers. It also picked up a “notorious” label thanks to a few very specific trouble spots.

If you’re wondering “Is the 5.4 Triton a good motor,” you probably want the truth without the internet drama. I’ll give you my straight take. This engine can serve you well if you understand which version you’re buying, what common problems to watch for, and how to maintain it. Some years run like a faithful farm dog. Others need proactive timing work and careful spark plug service. I’ll break it down in plain English, with real-world examples, so you can buy or own with confidence.

One quick note on wording. People say “motor” in conversation though this is a gasoline engine. Don’t confuse it with electric motors that have a stator and rotor. If that distinction helps you while you research, here are simple primers on the motor principle and how a stator and rotor work. You don’t need them to understand the Triton, but I see the terminology mix-up all the time.

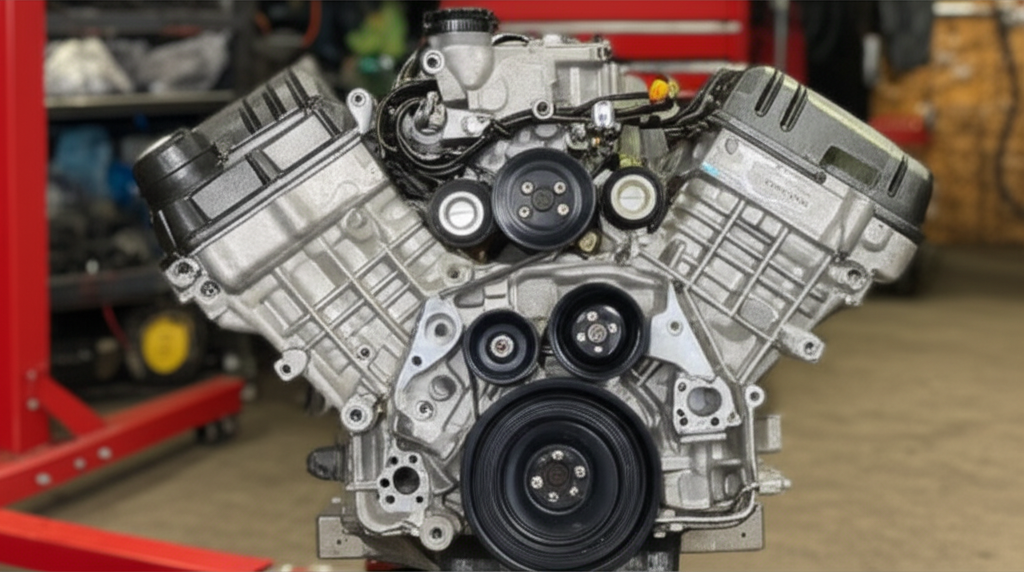

Generations of the 5.4L Triton: 2-Valve vs. 3-Valve Engines

When someone says “5.4 Triton,” they usually mean one of two flavors: the 2-valve (2V) or the 3-valve (3V). Same displacement. Very different ownership experience.

The 2-Valve 5.4L Triton (1997–2004): Simpler Design, Fewer Systemic Flaws

My first 5.4 came in a 1999 F-150. It was a 2V engine and it felt simple and stout. This version lacks the Variable Cam Timing (VCT) system that made the later 3V more powerful but also more complicated. You’ll see the 2V in 1997–2003 F-150s, the early Expeditions, and many E-Series vans and Super Duty trucks of that era.

How did it hold up for me? Very well. The 2V often gets high marks for long-term durability. I’ve seen these engines go past 250,000 miles with basic maintenance. You’ll hear about spark plug ejection on some 2V heads due to short thread engagement. It’s real. I’ve dealt with a blown plug in a friend’s 2002. We repaired the threads with an insert and moved on. It wasn’t fun, yet it wasn’t the end of the world either. Exhaust manifold studs can also snap and cause an annoying tick. I’ve replaced more than a few. It’s a common Ford truck thing.

Big picture on the 2V:

- Reliability: Generally robust with fewer systemic flaws.

- Common problems: Spark plug ejection on some heads, exhaust manifold stud breakage.

- Life expectancy: 200,000–300,000+ miles is common with good care.

- Applications: Ford F-150, Expedition, E-Series, and Super Duty in earlier years.

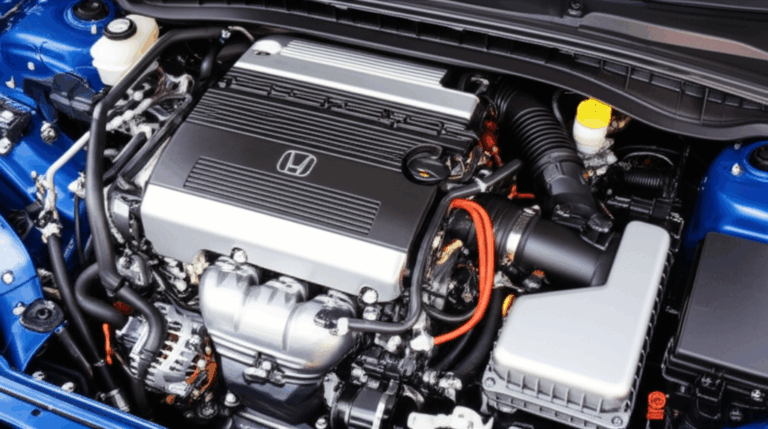

The 3-Valve 5.4L Triton (2004–2010+, some models to 2014): Enhanced Performance, Increased Complexity

Ford updated the 5.4 around 2004 with a 3-valve head and VCT. Power jumped. So did complexity. The 3V showed up in 2004–2008 F-150s, later Expeditions and Navigators, E-Series vans, and some Super Duty applications. Certain models kept it into the early 2010s.

I’ve driven a handful of 3V trucks and I’ve worked through the usual suspects. The engine makes stronger horsepower and torque than the 2V, which makes towing feel easier. The tradeoff sits under the timing cover. Cam phasers rely on clean oil pressure and a healthy timing set. When that system wears or starves, the engine starts to rattle and the trouble begins. Spark plug breakage during removal also haunts early 3V years due to a two-piece plug design and carbon buildup. I’ve used extraction tools more than once.

Why does the 3V wear a “bad” label?

- Cam phaser and VCT issues are common, especially on 2004–2008.

- Timing chains, guides, and tensioners often need service when phasers go.

- Spark plugs break on removal if you don’t follow best practices and use updated one-piece replacements.

Is it all doom and gloom? No. I’ve seen many 3V engines go past 200,000 miles after a proper timing job and careful maintenance. You just have to know what you’re buying and plan for the likely repairs.

The Notorious 5.4L Triton Problems: What to Expect

I don’t sugarcoat these. If you own or plan to own a 5.4 Triton, you should know what’s common, how to spot it, and what it costs.

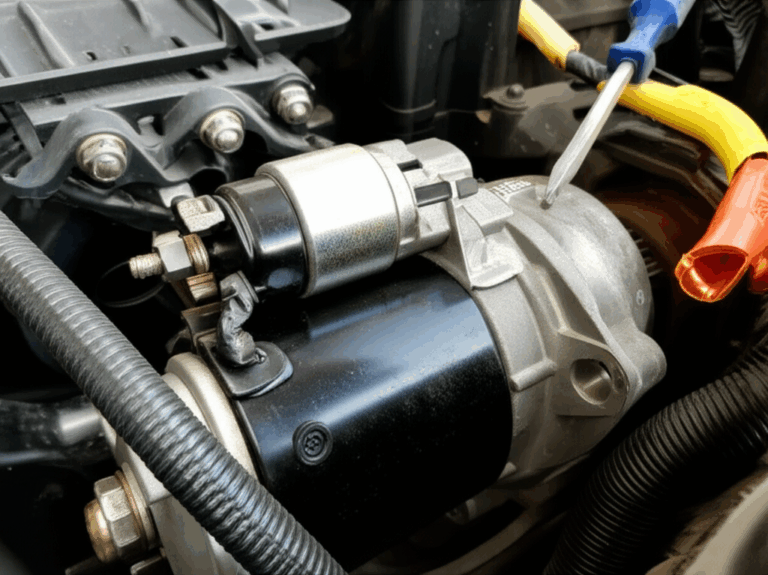

Cam Phasers and VCT System Failure (3-Valve Specific)

This is the big one. On 3V engines, the VCT system adjusts cam timing with oil pressure. When phasers wear or oil pressure drops, the truck starts to tick or knock. I’ve heard that unmistakable diesel-like clatter at idle on a 2006 F-150 that came into a buddy’s driveway. The owner thought it was the exhaust. It wasn’t.

You’ll usually see:

- Ticking or knocking at idle and low RPM, sometimes louder when warm.

- Rough idle and reduced power.

- Check Engine Light. Codes P0011, P0012, P0021, P0022 may pop up.

You fix this with a comprehensive timing job. That means cam phasers, VCT solenoids, chains, guides, and tensioners. Some shops add an oil pump. Quality parts matter. I’ve seen costs vary by region and shop. A full job is not cheap. The upside is big. Engines that get this service often run quietly and reliably for many more miles.

Key takeaways:

- 3V cam phasers fail often, especially on 2004–2008.

- Oil pressure and cleanliness are critical.

- A complete timing service usually beats piecemeal fixes.

Spark Plug Breakage and Ejection

This topic splits by generation.

- 3V spark plug breakage: If you have 2004–2008 original plugs, they can break during removal because of a two-piece design and carbon buildup in the head. I helped on a 2005 Expedition where two plugs snapped and we had to use a specialty removal tool. Expect extra labor and some frustration. Good news. If you install the updated one-piece plugs and follow the proper removal procedure next time, it’s often a one-time headache.

- 2V spark plug ejection: Some 2V heads have limited thread engagement. Under load, a plug can eject and take the threads with it. I’ve seen the aftermath. We installed a thread repair insert and the truck kept working. Not fun. Fixable.

What I do:

- Warm the engine before removal. Use penetrant. Take it slow.

- Follow Ford’s updated removal procedure on 3V plugs.

- Install the updated Motorcraft spark plugs (replacing the problematic early design).

- Stick with the correct torque specs on reinstall.

Timing Chain and Guide Wear (Mostly 3-Valve)

On 3V engines, timing chain guides and tensioners wear as miles pile up and as oil pressure dips. You’ll hear a rattle on cold starts or a persistent chatter at idle. I treat this as part of the cam phaser story. If I’m in there for phasers, I replace chains, guides, and tensioners. Do it once. Do it right.

Symptoms and connections:

- Rattling noise that tracks with RPM.

- Chain slack from worn guides and tensioners.

- Low oil pressure and sludge accelerate the wear.

- Mis-timed cams can cause poor performance and more codes.

Low Oil Pressure and Sludge Buildup

If there’s one maintenance theme for the 5.4 3V, this is it. Oil is everything. The VCT system lives on clean oil and correct viscosity. I’ve seen the difference. Engines that get 5W-20 synthetic blend or full synthetic at 3,000–5,000 mile intervals tend to avoid the worst. Owners who stretch oil changes or run the wrong viscosity invite sludge, low oil pressure, phaser rattle, and timing wear.

Practical notes:

- Stick to 5W-20 unless your specific application calls for something else.

- I prefer synthetic blend or full synthetic.

- Shorter intervals beat long ones on these engines.

- If the engine knocks after an oil change, verify viscosity and oil level. Wrong viscosity can make noise worse.

Exhaust Manifold Studs and Ticking

Both 2V and 3V engines break exhaust manifold studs. Road salt and heat do them in. You’ll hear a ticking on cold starts that quiets down as the metal expands. I’ve replaced studs on a 2V and a 3V. It’s tedious. It’s common. If a shop quotes replacement, I don’t get mad about it. I’ve been there on the other side of the wrench.

A Few Other Issues I Watch For

Not every engine gets these, but I keep my eyes open:

- Vacuum leaks that cause a rough idle or misfire.

- PCV valve and hose issues that lead to oil consumption or lean codes.

- EGR valve faults that trigger the Check Engine Light.

- COPs (coil-on-plug) failures that cause an intermittent misfire.

- Catalytic converter and oxygen sensor issues after long miles.

- Throttle body buildup that makes idle wonky.

- Valve cover gaskets that seep and cook on hot exhaust surfaces.

- Roller followers or lifter noise on high-mile 3V engines.

I also listen for engine tapping after an oil change. If the viscosity is off or the filter drains back poorly, a 3V can sound unhappy. I correct the oil and filter first before I panic.

If you’re the type who loves diagnosing mechanical gremlins, this short read on common motor problem patterns can help you think systematically. Different technology, same problem-solving mindset.

Strengths and Advantages of the 5.4L Triton

For all the drama, the 5.4 Triton still brings real strengths to the table. I’ve leaned on them many times.

- Adequate power and torque: The engine isn’t a drag-strip hero. It pulls trailers and loads well for its era. You’ll get workable towing capacity in F-150s, Expeditions, and Super Duty setups when the truck is configured right.

- Potential for longevity: I’ve seen 2V engines cross 300,000 miles with basic maintenance. I’ve also seen 3V engines do 200,000 miles plus after a proper timing service. Many owners report similar outcomes.

- Parts availability: You can find OEM parts, remanufactured components, and aftermarket options easily. Rock Auto and dealer networks carry what you need. Mechanic familiarity helps keep labor costs reasonable in many markets.

- Affordable used vehicle price: Trucks and SUVs with the 5.4 often cost less than newer Coyote V8 trucks or EcoBoosts. You buy more truck for the dollar if you plan for a timing job or other known issues.

Performance and Fuel Economy Overview

I never bought a 5.4 Triton for fuel economy. You probably aren’t either.

- Power output:

- 2V: Generally in the mid-200 horsepower range with solid torque for the time.

- 3V: Around 300 horsepower and roughly 365 lb-ft of torque depending on year and application. That felt like a nice jump in real-world towing.

- Fuel economy:

- Real-world numbers often land around 12–14 MPG city and 16–18 MPG highway for 4×4 half-ton trucks of the era. A 2WD truck can do a bit better. A heavy SUV or van can do worse.

- By modern standards, the 5.4 drinks fuel. It comes with the territory.

- Towing and payload:

- You can tow in the 9,000–10,000 pound range in the right F-150 configuration. Heavier chassis like Super Duty step that up. Check your specific truck’s tow rating and axle ratio.

Is the 5.4 Triton a Good Motor for You? Buying and Ownership Considerations

When someone asks me this, I start with their expectations. Do you want a budget-friendly truck or SUV that can tow and haul? Are you willing to do proactive maintenance? If that sounds like you, the 5.4 can work well.

Crucial Pre-Purchase Inspection Points

I never buy a 5.4 without doing this checklist:

- Listen for ticking or knocking at idle. A cold start tells the truth on phasers and timing chain noise.

- Scan for codes. P0011, P0012, P0021, and P0022 point to VCT issues on 3V engines. Misfire or lean codes may point to vacuum leaks, coils, or fuel issues.

- Ask for maintenance records. I want proof of regular oil changes with the correct viscosity. I like to see 3,000–5,000 mile intervals.

- Ask about spark plug history on 3V engines. If they’re original on a 2004–2008, I plan for a careful removal process and potential breakage.

- Check for exhaust leaks. A ticking that fades as the truck warms up can be a manifold leak.

- Look for oil leaks at valve covers and the timing cover.

- Inspect the cooling system, serpentine belt, alternator, and water pump. They’re normal wear items that can stack up.

- Look for signs of neglected maintenance. Sludge under the oil cap or coked-up throttle bodies tell a story.

Model Years to Prioritize or Avoid

Every used market is different. I follow this general rule:

- 2V (1997–2004): Usually the safer long-haul bet. Simpler. Fewer systemic flaws. Still watch for spark plug ejection and manifold studs.

- Early 3V (2004–2008 F-150 era): Most likely to need a full timing job and careful spark plug service if those haven’t been done. Many owners flag these as the “years to avoid” unless you document repairs.

- Later 3V: I’ve seen fewer spark plug breakage issues when updated one-piece plugs are already installed. Timing work can still be necessary as miles add up, yet some later examples seem less troublesome. Expedition, Navigator, and E-Series ran the 3V later than the F-150. Check the build year and service history closely.

If you’re shopping a 2009–2010 F-150 with the 5.4 3V, take a hard look at whether it already had timing and phaser service. A documented repair makes that truck far more attractive in my book.

The Importance of Maintenance Records

I treat maintenance records as non-negotiable. A 3V engine that got regular 5W-20 and short intervals often looks inside like it should. Sludge kills these engines. Clean oil saves them. If you’re considering a high-mile 2V, records still matter. They help you judge how the previous owner treated the truck.

Budgeting for Potential Repairs

When I pencil this out for friends:

- 3V timing job: It’s the big-ticket repair. A complete service with phasers, chains, guides, tensioners, VCT solenoids, and possibly an oil pump makes or breaks long-term reliability. Plan for it unless it’s documented as done with quality parts.

- 3V spark plug service: If the plugs are original, build in extra labor for an extraction tool scenario.

- Exhaust manifold studs: Budget for broken studs if you hear that telltale tick.

- Other wear items: Coils, injectors, PCV valves, O2 sensors, and valve cover gaskets add up over time. None of those are exotic.

I don’t throw exact dollar figures around unless I’ve seen the truck in front of me. Regional labor rates vary a lot. Parts price swings between OEM, remanufactured, and aftermarket options also matter.

Maximizing Your 5.4L Triton’s Lifespan: Essential Maintenance Tips

You can squeeze a lot of life out of these engines. I stick to a simple playbook that has paid off for me.

- Use the right oil:

- 5W-20 synthetic blend or full synthetic works well in most applications.

- Change it every 3,000–5,000 miles. I don’t push longer intervals on the 3V.

- If you notice engine tapping after an oil change, verify viscosity, level, and the filter’s anti-drainback performance.

- Keep the VCT system happy:

- On a 3V, treat the VCT solenoids as maintenance items. Replace them proactively if you suspect slow response or see related codes.

- Don’t ignore early ticking or rattling. Early action can save other parts.

- Handle spark plugs the right way:

- Warm the engine. Use penetrant. Follow the proper removal procedure on 3V engines to reduce breakage risk.

- Replace early two-piece plugs with updated one-piece units (Motorcraft SP-515 equivalents).

- Use the correct torque.

- Watch the timing set:

- If you own a 3V past 150,000 miles and you hear consistent rattle, plan a timing job. I replace phasers, chains, guides, tensioners, and usually the VCT solenoids together.

- Keep the rest of the engine healthy:

- Replace the PCV valve and hoses as needed. A stuck PCV can raise oil consumption and create vacuum leaks.

- Clean the throttle body to smooth the idle.

- Repair exhaust manifold studs to prevent hot leaks that cook nearby parts.

- Stay ahead of cooling system service. Overheating never helps timing components.

- Use quality OEM or reputable aftermarket parts. I’ve had good luck mixing OEM with high-quality aftermarket when the budget demanded it.

- Fuel and emissions:

- If you see the Check Engine Light, scan it. Misfire codes point me toward coils and plugs first. Lean codes push me toward vacuum leaks, PCV, or MAF/throttle body issues.

- Catalytic converter efficiency codes show up on high-mile engines. It’s not unusual.

- If you tow:

- Change fluids more often. Heat kills oil and ATF quickly under heavy loads.

- Make sure your gearing and tow package match the trailer weight.

Quick Comparisons: 5.4 Triton vs 5.0 Coyote vs 6.2L V8

I’ve driven all three in different trucks. Here’s how they shake out for me.

- 5.4 Triton vs 5.0 Coyote:

- The 5.0 Coyote makes more power with less drama. It revs better, it sips a little less fuel, and it avoids the 3V’s cam phaser saga. Coyote trucks cost more on the used market. If your budget allows, the Coyote is the stronger everyday choice. If your budget is tight, a 5.4 with documented timing work can be a smart buy.

- 5.4 Triton vs 6.2L V8:

- The 6.2 hauls. It’s a torque monster in Super Duty applications. It also drinks more. If you tow heavy and you want a modern-feeling big V8, the 6.2 wins. If you’re shopping lower-priced half-tons or older SUVs, the 5.4 is more accessible.

- 5.4 Triton vs 4.6L V8:

- The 4.6 often lasts a long time and runs simpler. It gives up torque to the 5.4. Towing feels easier with the 5.4 if you’re moving real weight.

- A quick nod to the Triton V10:

- The V10 tows like a champ in heavy chassis. Fuel economy goes out the window. If you need capability above all else, the V10 fits. For daily use, the 5.4 costs less to run.

Conclusion: A Nuanced Verdict on the 5.4L Triton

So is the 5.4 Triton a good engine? My answer lives in the details.

- The 2V (1997–2004) is the safer bet for long-term reliability. I’ve seen many of them pass 250,000 miles. Watch for spark plug ejection on specific heads and broken manifold studs. Otherwise the design stays simple and strong.

- The 3V (2004–2010 in the F-150 and in some models through the early 2010s) can be a good engine if you handle its known issues. Cam phasers and VCT depend on clean oil and good pressure. Timing sets wear. Early spark plugs break during removal. If you buy a 3V with documented timing service and updated plugs, you can enjoy solid power and long life. If you ignore the noise, it will cost you later.

I’d buy a 5.4 Triton again. I’d check the year and generation first. I’d ask for service records and listen for the telltale idle sounds. I’d budget for a timing job on any 3V that hasn’t had one. I’d use the correct 5W-20 oil and short intervals. Do that and you’ll own a dependable V8 that still pulls its weight.

If you’re new to the “engine vs motor” wording and you want a basic refresher while you shop, here’s a simple guide to the motor principle. The 5.4 Triton is an internal combustion engine, yet the diagnostic mindset carries over no matter what you spin, crank, or turn.