The 3 Basic Types of Split-Phase Motors: A Comprehensive Guide to Function and Application

Every design engineer and procurement manager eventually faces a critical challenge: selecting the right motor for an application powered by single-phase AC. It’s a landscape filled with trade-offs between starting torque, running efficiency, cost, and complexity. If you’ve ever found yourself weighing these factors, particularly for household appliances, HVAC systems, or light industrial equipment, you’ve likely encountered the term “split-phase motor.” But what does that really mean, and how do you choose the right one?

You’re in the right place. This guide is designed to act as your knowledgeable engineering partner. We’ll break down the three fundamental types of split-phase motors, demystify how they work, and provide clear guidance on where each one shines. We’ll move past the dense textbook definitions to give you the practical knowledge needed to make confident design and purchasing decisions.

What We’ll Cover

- The Starting Problem: Why single-phase motors need a “kick-start” in the first place.

- Type 1: Resistance-Start Induction Run Motor – The simple, cost-effective workhorse.

- Type 2: Capacitor-Start Induction Run Motor – The high-torque powerhouse.

- Type 3: Permanent Split Capacitor (PSC) Motor – The quiet, efficient operator.

- Head-to-Head Comparison: A clear breakdown of key differences to guide your selection.

- Anatomy of a Split-Phase Motor: Understanding the core components that make them tick.

- Your Engineering Takeaway: Actionable advice for your next project.

The Fundamental Challenge: Kicking a Single-Phase Motor into Action

Before we dive into the specific types, it’s crucial to understand why we need to “split” a phase at all. A standard single-phase AC motor, with just one main winding, has a problem. The alternating current creates a magnetic field that pulses back and forth—it gets stronger, weaker, and reverses polarity, but it doesn’t rotate.

Think of it like trying to push a merry-go-round by standing directly in front of it and just pushing and pulling along a single line. You’ll make it shake, but you’ll never get it to spin. To create rotation, you need to give it a push from the side.

That’s precisely the job of the split-phase mechanism. It uses a second, auxiliary winding (also called a start winding) to create a second, out-of-sync magnetic field. This time-delayed “push from the side” generates a weak, lopsided rotating magnetic field—just enough to get the rotor turning. Once it’s up to speed, the motor can continue running on the main winding alone, much like that merry-go-round will keep spinning with occasional pushes once its momentum is established.

The three basic types of split-phase motors are all defined by how they create this out-of-sync magnetic field.

1. Resistance-Start Induction Run (Standard Split-Phase) Motor

The resistance-start motor is the original and most straightforward design in the split-phase family. It’s the very definition of a simple, no-frills solution designed for one thing: getting light loads moving as economically as possible.

How It Works: The Path of Most Resistance

This motor’s cleverness lies in its winding design. It features two windings: the main (run) winding and the auxiliary (start) winding.

- Main Winding: This is built with thicker copper wire, giving it low resistance but high reactance (an opposition to change in current).

- Auxiliary Winding: This is the key to its operation. It’s wound with a smaller diameter wire, resulting in a much higher resistance and lower reactance compared to the main winding.

When you power up the motor, current flows through both windings in parallel. Because of their different electrical properties (resistance vs. reactance), the current flowing through the high-resistance auxiliary winding peaks slightly before the current in the main winding. This small time difference, or phase shift, is enough to create that initial rotating magnetic field we talked about. It’s not a powerful or efficient field, but it works.

Once the motor spins up to about 70-80% of its full rated speed, a centrifugal switch springs into action. This mechanical switch is mounted on the motor’s shaft and is designed to open at a specific RPM. When it opens, it completely disconnects the auxiliary winding from the circuit. The motor then continues to run solely on its more efficient main winding.

Key Characteristics

- Starting Torque: Low. Typically around 125% to 175% of its full-load torque. It’s just enough to overcome the inertia of easy-to-start loads.

- Starting Current: Very high. This is its biggest drawback. The initial current draw can be 6 to 8 times the motor’s full-load running current, which can cause voltage dips or trip breakers if not managed.

- Cost & Simplicity: This is the most economical and mechanically simple of the three types, containing no capacitors.

Common Applications

You’ll find resistance-start motors where the load is minimal at startup. Think of applications that don’t have to fight against a lot of initial friction or pressure.

- Small bench grinders

- Light-duty blowers and fans

- Oil burners in furnaces

- Some small washing machines (older models)

2. Capacitor-Start Induction Run Motor

What if you need to start a load that’s a bit more stubborn? Imagine an air compressor that has to push against pressurized air in the tank, or a conveyor belt loaded with heavy boxes. For these jobs, the low starting torque of a resistance-start motor just won’t cut it. Enter the capacitor-start motor—the high-torque powerhouse of the group.

How It Works: A Jolt of Starting Power

The capacitor-start motor builds on the resistance-start design with one critical addition: a start capacitor wired in series with the auxiliary winding and the centrifugal switch.

A capacitor is an electrical component that stores and releases energy. In this circuit, it has a profound effect on the phase shift. By placing it in series with the start winding, it causes the current in that winding to lead the voltage, creating a much larger phase difference between the start and main windings—much closer to the ideal 90 degrees.

Think of our merry-go-round analogy again. The resistance-start motor gave it a weak shove from the side. The capacitor-start motor gives it a perfectly timed, powerful heave that gets it spinning with authority. This results in a significantly stronger and more uniform rotating magnetic field at startup.

Just like the resistance-start motor, once it reaches about 75% of its operating speed, the centrifugal switch opens. This time, it disconnects both the auxiliary winding and the start capacitor, leaving the motor to run efficiently on its main winding. The interaction between the fields in the stator and rotor is what ultimately drives the machine, but that powerful starting kick is what makes it suitable for tough jobs.

Key Characteristics

- Starting Torque: High to very high. We’re talking 200% to 400% (or even more) of the full-load torque. This is its signature feature.

- Starting Current: While still significant, the starting current is noticeably lower than that of a resistance-start motor for the same amount of starting torque, making it more efficient at getting things moving.

- Cost: The addition of a capacitor and a slightly more robust design makes it more expensive than the standard split-phase motor.

Common Applications

You’ll find these motors anywhere a significant amount of “grunt” is needed to get the job started from a dead stop.

- Air compressors

- Refrigeration units

- Large pumps and conveyors

- Heavy-duty power tools (e.g., large table saws)

- Farm equipment

3. Permanent Split Capacitor (PSC) Motor

The first two motors we discussed are all about the start. Their auxiliary windings are temporary helpers that get switched off once the job is done. But what if you need a motor that’s not just a good starter but also a highly efficient and quiet runner? That’s where the Permanent Split Capacitor (PSC) motor comes in. It represents a more refined and modern approach to single-phase motor design.

How It Works: The Balanced Performer

The PSC motor’s design is elegant in its simplicity. It has a main winding and an auxiliary winding, but here’s the twist: it uses a run capacitor that is permanently wired in series with the auxiliary winding. Crucially, there is no centrifugal switch.

This means the auxiliary winding and the run capacitor are active the entire time the motor is running, not just during startup. The run capacitor is specifically chosen to optimize the phase shift for running conditions, not starting ones. This creates a balanced, two-phase effect while the motor is operating, leading to several key benefits.

Because the capacitor is always in the circuit, it helps improve the motor’s running efficiency and power factor. A better power factor means the motor uses the supplied electricity more effectively, reducing waste heat and lowering energy consumption. The continuous two-phase field also results in smoother, quieter operation with less vibration.

Key Characteristics

- Starting Torque: Low to moderate. Typically only 50% to 100% of the full-load torque. It’s not designed for hard-starting applications.

- Running Efficiency & Power Factor: Excellent. This is its primary advantage. PSC motors are significantly more energy-efficient during continuous operation than the other types.

- Quiet Operation: The balanced magnetic fields result in a motor that runs much more smoothly and quietly.

- Reliability: The absence of a mechanical centrifugal switch removes a common point of failure, making PSC motors very reliable.

- Speed Control: They are often easily speed-controlled by varying the voltage.

Common Applications

PSC motors are the go-to choice for applications that run for long periods and where energy efficiency and low noise are important. They are ubiquitous in modern appliances.

- HVAC fans and blowers (indoor and outdoor units)

- Refrigerator and freezer compressor motors

- Washing machine and dishwasher pump motors

- Ceiling fans

- Office machines

Key Differences: How to Choose the Right Type

Choosing the right motor boils down to matching its characteristics to your application’s demands. Let’s put them side-by-side to make the decision clearer.

| Feature/Metric | Resistance-Start Induction Run | Capacitor-Start Induction Run | Permanent Split Capacitor (PSC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starting Torque | Low (125-175%) | Very High (200-400%+) | Low (50-100%) |

| Starting Current | Very High | Moderate | Low |

| Running Efficiency | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Power Factor | Low (0.5 – 0.6) | Moderate (0.6 – 0.7) | High (0.8 – 0.9) |

| Relative Cost | Lowest | Moderate | Highest |

| Key Component | Centrifugal Switch | Centrifugal Switch & Start Capacitor | Run Capacitor (No Switch) |

| Best For… | Light, easy-to-start loads where cost is paramount. | Hard-to-start loads requiring high breakaway torque. | Continuous-run applications where efficiency and low noise are critical. |

Your Decision Checklist:

- Hard (e.g., compressor, loaded conveyor): You need a Capacitor-Start motor. No question.

- Easy (e.g., small fan, grinder): A Resistance-Start motor is a cost-effective choice.

- Moderate (e.g., appliance pump, HVAC blower): A PSC motor will handle it just fine.

- Intermittently: The lower efficiency of a resistance-start or capacitor-start motor is less of a concern.

- Continuously (hours a day): The energy savings from a PSC motor will quickly pay for its higher initial cost.

- If quiet operation is a priority (like in a home appliance or office environment), the PSC motor is the clear winner.

Essential Components of Split-Phase Motors

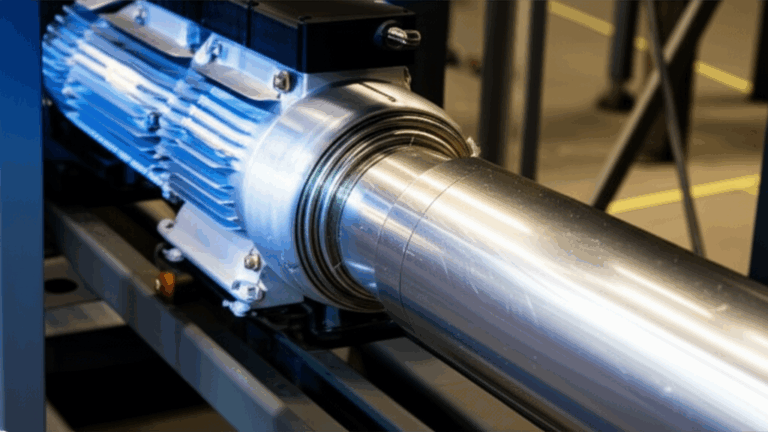

Understanding the key players inside the motor housing helps in both selection and troubleshooting. The quality and design of these parts, especially the magnetic core built from motor core laminations, dictate the motor’s overall performance and lifespan.

- Main (Run) Winding: The primary set of coils inside the stator. It’s designed to be highly efficient for continuous operation after the motor is up to speed.

- Auxiliary (Start) Winding: The secondary set of coils used to create the phase shift for starting. In resistance-start and capacitor-start motors, it is only energized for a few seconds. In a PSC motor, it’s active continuously.

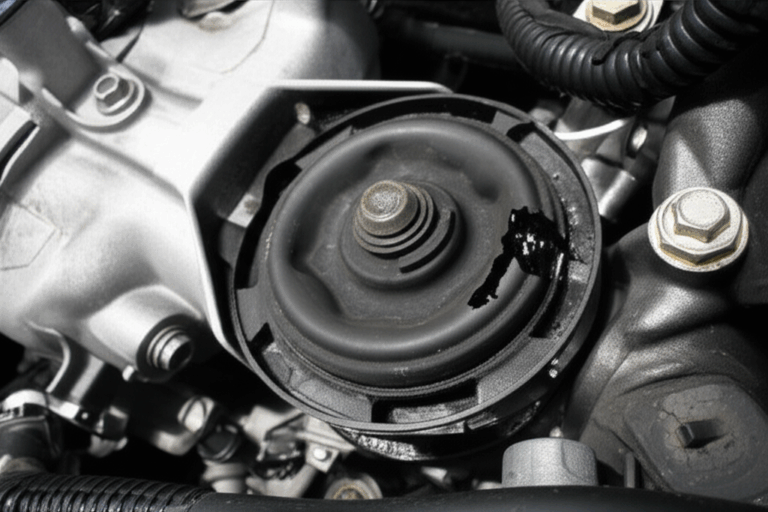

- Centrifugal Switch: A mechanical device found only in resistance-start and capacitor-start motors. It’s a common point of failure; if it gets stuck open, the motor won’t start, and if it gets stuck closed, the start winding will quickly overheat and burn out.

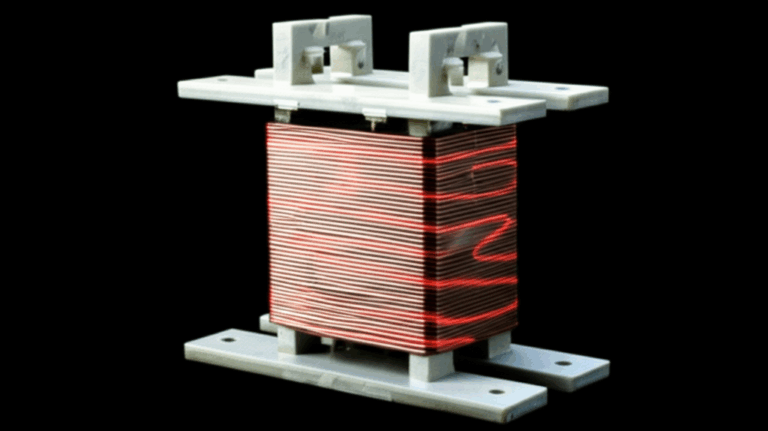

- Start Capacitor: Found only in capacitor-start motors. It’s designed for intermittent, high-energy bursts and will fail if left in the circuit for too long.

- Run Capacitor: Found only in PSC motors. It’s designed for continuous duty and is crucial for maintaining the motor’s efficiency and power factor.

- Stator & Rotor: The stator is the stationary part of the motor containing the windings, typically built from high-quality stator core lamination to manage the magnetic fields effectively. The rotor is the rotating part, and in these motors, it’s almost always a “squirrel cage” design. The quality of the rotor core lamination is just as vital for minimizing energy losses and ensuring smooth rotation.

Your Engineering Takeaway

The world of single-phase motors doesn’t have to be complex. By understanding the core principles and distinct roles of these three split-phase types, you can move from uncertainty to confident decision-making.

Here’s a simple summary to guide your next project:

- For low-cost, light-duty applications, the Resistance-Start motor is a simple and economical choice.

- For demanding applications that require high starting torque, the Capacitor-Start motor is the robust solution you need.

- For applications that run continuously and demand high efficiency and quiet operation, the Permanent Split Capacitor (PSC) motor is the modern, reliable, and energy-conscious option.

Ultimately, selecting the correct split-phase motor isn’t just a technical detail—it’s a critical decision that impacts your product’s performance, reliability, and long-term operating cost. By arming yourself with this knowledge, you are better equipped to specify the perfect motor for the job and have more productive conversations with your suppliers.