The Invisible Stop: How Eddy Currents Power Electromagnetic Braking Systems

Of course. Here is the article, written according to your specific instructions.

Table of Contents

- Revolutionizing Braking with Electromagnetism

- Understanding Eddy Currents: The Physics Behind the Force

- What Exactly Are Eddy Currents?

- Lenz’s Law: The Guiding Principle of Opposition

- The Core Mechanism: How Eddy Currents Generate Braking Force

- Setting the Stage: The Key Players in Motion

- The Braking Process: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

- The Key Components of an Eddy Current Braking System

- The Magnets: Permanent vs. Electromagnets

- The Conductor: Where the Magic Happens

- The Control System: The Brains of the Operation

- Advantages of Eddy Current Braking: Why I’m a Fan of Contactless Stopping

- The Other Side of the Coin: Limitations and Challenges of Eddy Current Brakes

- Real-World Applications: Where I’ve Seen Eddy Currents Make a Difference

- High-Speed Trains: Stopping from Blazing Speeds

- Roller Coasters and Amusement Rides: The Ultimate Safety Net

- Industrial Machinery and Heavy Vehicles: The Unsung Heroes

- Fitness Equipment: Your Smooth Workout Partner

- Conclusion: The Future of Braking Technology is Electromagnetic

Revolutionizing Braking with Electromagnetism

I’ll never forget the first time I rode a modern roller coaster—one of those that launches you from zero to a hundred miles per hour in a couple of seconds. The acceleration was breathtaking but what truly stuck with me was the stop. There was no screeching, no shuddering, just a powerful, impossibly smooth deceleration that brought the entire train to a halt in what felt like a few heartbeats.

I later learned that this silent, invisible force wasn’t powered by traditional friction brakes. It was electromagnetic braking and at its heart was a fascinating phenomenon called eddy currents.

For most of my life, I associated braking with the familiar squeal of tires or the grinding of brake pads on a rotor. It’s a system of controlled friction that works incredibly well but it has its downsides: wear and tear, noise, and maintenance. What I’ve come to appreciate over the years is the elegance of a system that can stop a speeding vehicle without ever touching it.

In this article, I want to pull back the curtain on this amazing technology. We’ll dive into what eddy currents are, explore the physics that make them work, and look at how they’re being used to make everything from trains to exercise bikes safer, quieter, and more reliable. This isn’t just a science lesson; it’s a look into a revolutionary approach to controlling motion.

Understanding Eddy Currents: The Physics Behind the Force

Before we can talk about braking, we need to understand the star of the show: the eddy current. The name might sound a little strange, but the concept is surprisingly intuitive once you get the hang of it. I remember it finally clicking for me when I saw a simple physics demonstration, and I’ll share that with you in a moment.

What Exactly Are Eddy Currents?

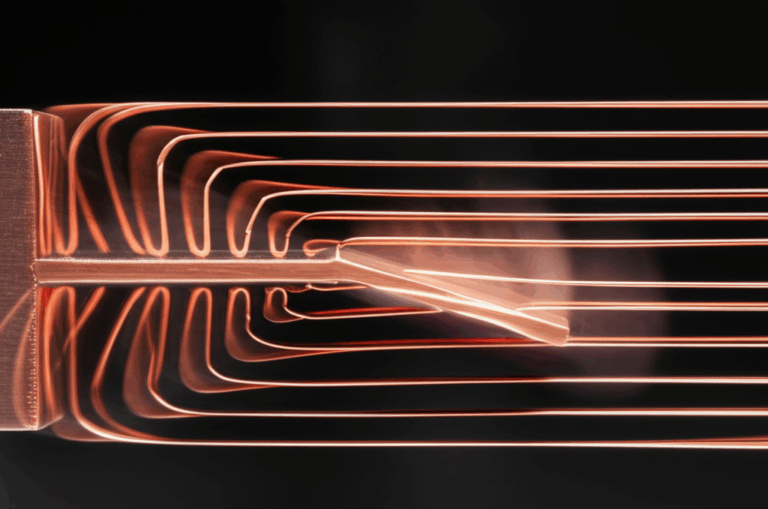

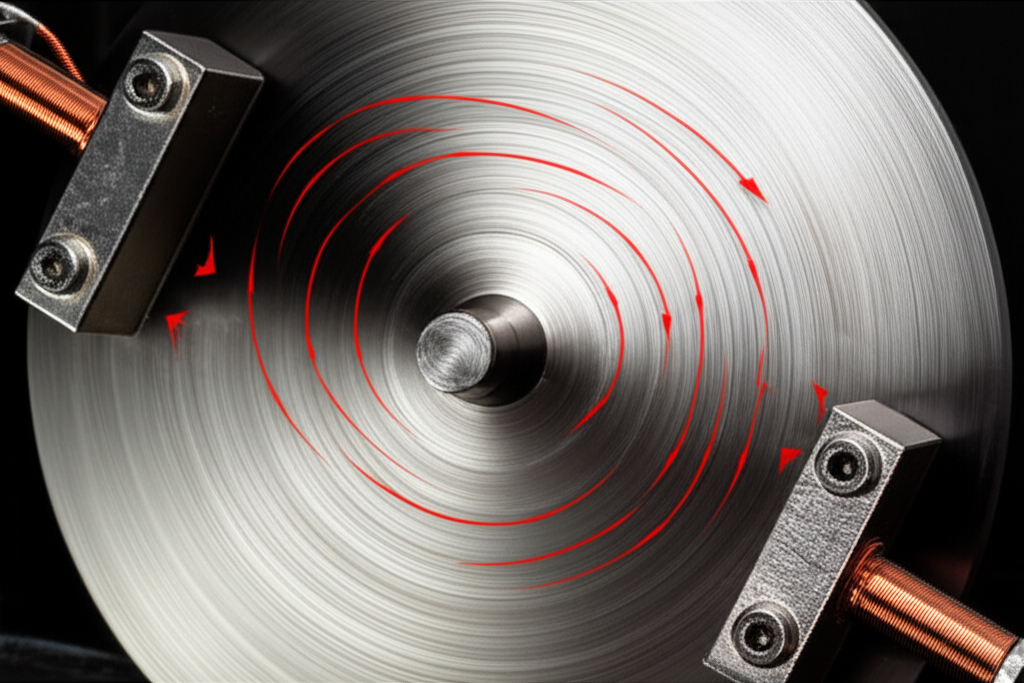

At its core, an eddy current is a localized, circular flow of electricity induced within a conductor. Think of them like little whirlpools or “eddies” of electrical current swirling inside a piece of metal. These currents don’t just appear out of nowhere; they are a direct result of a principle called electromagnetic induction, which the brilliant scientist Michael Faraday discovered.

Here’s the simple version: whenever you move a conductor (like a copper or aluminum plate) through a magnetic field, or change the magnetic field around a stationary conductor, you generate these tiny circular currents inside the material. These are also sometimes referred to as Foucault currents, after the French physicist Léon Foucault who discovered them.

The key takeaway is this: relative motion between a magnet and a conductor creates electricity inside that conductor. It’s this simple fact that forms the foundation for everything we’re about to discuss.

Lenz’s Law: The Guiding Principle of Opposition

Now, here’s where it gets really interesting and where the braking force comes from. These induced eddy currents aren’t just passive bystanders. According to a principle called Lenz’s Law, they generate their own magnetic field. And this new magnetic field is a bit of a rebel—it always opposes the very change that created it in the first place.

This is the “aha!” moment for most people, myself included.

Let me give you that classic analogy I mentioned: Imagine you have a thick copper pipe and a strong magnet. If you drop a non-magnetic piece of steel down the pipe, it falls right through. No surprise there. But if you drop the magnet down the pipe, something incredible happens. It falls in slow motion, as if it’s moving through invisible molasses.

Why? As the magnet falls, its moving magnetic field induces eddy currents in the walls of the copper pipe. Those eddy currents, following Lenz’s Law, create their own magnetic field that pushes back up against the falling magnet, opposing its motion. The pipe isn’t magnetic itself but it becomes an “electromagnetic brake” for the falling magnet.

This opposition, this drag force, is the entire secret behind how eddy currents are used in electromagnetic braking.

The Core Mechanism: How Eddy currents Generate Braking Force

With the physics of Lenz’s Law in our back pocket, we can now look at a practical braking system. It’s one thing to see a magnet fall slowly through a pipe; it’s another to see that same principle stop a 30-ton train. But I can assure you, the science is exactly the same. The main difference between a simple demonstration and a high-speed train is a matter of scale and engineering.

Setting the Stage: The Key Players in Motion

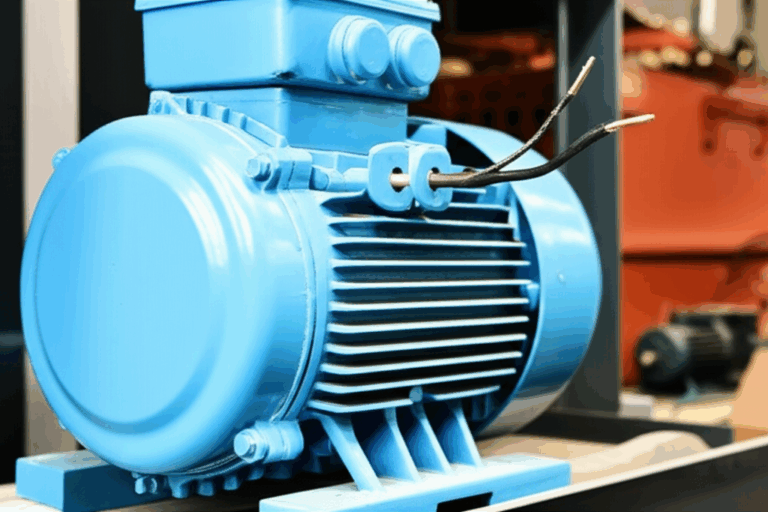

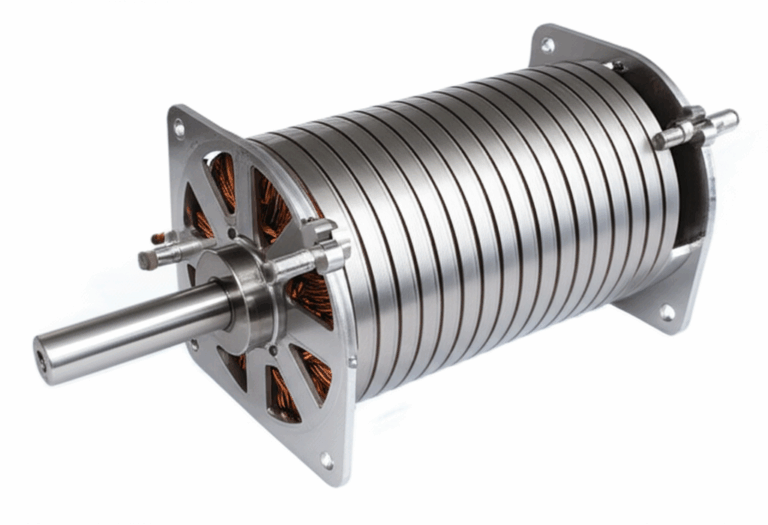

An eddy current braking system has two essential components that interact with each other. The relationship between these parts is similar to what you’d find in an electric motor, involving a stationary part and a moving part. In fact, many of the design principles for the stator and rotor in a motor apply here as well.

The Braking Process: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Let’s walk through what happens when you apply the brakes on a system using eddy currents. I’ll use the example of a roller coaster, where a metal fin on the car passes through a set of magnets on the track.

It’s a beautiful and elegant conversion of energy—from motion to electricity to heat—all without any parts physically touching.

The Key Components of an Eddy Current Braking System

When I first started studying these systems, I was amazed by their simplicity. Unlike a hydraulic friction brake with its calipers, pads, discs, and fluid lines, an eddy current brake is fundamentally just a magnet and a conductor. Of course, the engineering that goes into optimizing them is highly complex.

The Magnets: Permanent vs. Electromagnets

The choice of magnet is one of the most important design considerations.

- Electromagnets: These are the most common choice for applications that require variable braking. An electromagnet is essentially a coil of wire wrapped around an iron core. By controlling the amount of electricity flowing through the coil, you can precisely control the strength of the magnetic field and thus the braking force. This is crucial for applications like train service brakes or industrial dynamometers. The electromagnets are often built using high-quality materials, and the efficiency of the stator core lamination is critical for minimizing energy loss. The downside? They require a constant power source to operate.

- Permanent Magnets: These magnets, made from rare-earth materials like neodymium, have a fixed magnetic field. They are simpler, require no power, and are incredibly reliable, making them perfect for “fail-safe” emergency braking systems. For example, the brakes on many roller coasters use permanent magnets. If the power goes out, the brakes still work perfectly because their force is always present.

The Conductor: Where the Magic Happens

The conductor is the part that moves through the magnetic field, and its properties are just as important as the magnets. It’s typically a disc or a rail made of a non-ferromagnetic but highly conductive material.

- Material: Copper is an excellent conductor, but it’s heavy and expensive. Aluminum is a fantastic alternative because it’s lightweight, has great conductivity, and is more cost-effective.

- Design: The design of the conductor, or the “rotor,” is critical for both generating eddy currents and dissipating heat. In some designs, the rotor core lamination might be slotted to help direct the eddy current paths and improve performance. The ability to shed heat is vital because, in heavy-duty applications, all that kinetic energy turns into a massive amount of thermal energy.

The Control System: The Brains of the Operation

For systems using electromagnets, a sophisticated power electronics control system is required. This system precisely meters the electrical current sent to the electromagnet coils. This allows for smooth, variable braking force. For example, a train operator can apply a little braking force for a gentle slowdown or a massive amount for an emergency stop, all by adjusting the current. This level of control is simply not possible with many friction-based systems.

Advantages of Eddy Current Braking: Why I’m a Fan of Contactless Stopping

After years of working with and studying different mechanical systems, I’ve developed a deep appreciation for designs that prioritize simplicity, reliability, and low maintenance. Eddy current brakes check all of these boxes.

- No Contact, No Wear & Tear: This is the biggest advantage, hands down. Since nothing physically touches, there are no brake pads to wear out, no discs to warp, and no brake fluid to replace. This dramatically reduces maintenance costs and downtime. In heavy-use applications like city buses or theme park rides, the savings can be astronomical.

- Smooth and Precise Braking: The braking force is directly proportional to the relative speed (up to a point). This means the deceleration is incredibly smooth and predictable, without the jerking or grabbing you can sometimes feel with friction brakes.

- High Heat Dissipation Capacity: These systems are designed to convert massive amounts of kinetic energy into heat and are often equipped with cooling fins or other mechanisms to dissipate it effectively. This makes them ideal for slowing down heavy vehicles on long descents, where friction brakes could dangerously overheat.

- Quiet Operation: The absence of friction means the braking is virtually silent. This is a huge plus for passenger comfort on high-speed trains and for reducing noise pollution in urban environments.

- Reliability and Safety: With fewer moving parts and no wear components, eddy current brakes are exceptionally reliable. This is why they are so often used in safety-critical applications like emergency brakes on elevators and roller coasters.

- Effectiveness at High Speeds: The braking force generated by eddy currents increases as the speed increases. This makes them exceptionally good at scrubbing off a lot of speed quickly, which is perfect for high-speed rail.

The Other Side of the Coin: Limitations and Challenges of Eddy Current Brakes

As much as I admire this technology, it’s not a magic bullet. It has some inherent limitations that engineers have to design around. It’s important to understand these to see why eddy current brakes are often used in combination with other systems.

- No Holding Torque: This is the most significant limitation. Because the braking force depends on relative motion, an eddy current brake cannot hold an object completely still. As the speed approaches zero, the braking force drops to zero. This is why you’ll always see a secondary mechanical brake (like a parking brake on a truck or a simple friction clamp on a roller coaster) to hold the vehicle stationary once it has stopped.

- Heat Generation: While they are great at dissipating heat, that heat still has to go somewhere. In very demanding, continuous-use applications, managing this thermal load is a major engineering challenge. Robust cooling systems are often necessary.

- Ineffective at Low Speeds: As mentioned, the braking force diminishes at low speeds. This makes them less suitable as the sole braking system for a vehicle that needs precise control during slow-speed maneuvering.

- Energy Consumption (for Electromagnets): Systems that use electromagnets require a significant amount of electrical power to operate, which adds complexity and an energy cost to the system.

Because of these limitations, you often see eddy current brakes used in a hybrid approach. For example, a heavy truck might use its eddy current retarder for 90% of the braking on a long downhill grade, saving the friction brakes for the final stop and for holding the truck at a standstill.

Real-World Applications: Where I’ve Seen Eddy Currents Make a Difference

This technology isn’t just a lab experiment; it’s out in the world making transportation and industry safer and more efficient every single day.

High-Speed Trains: Stopping from Blazing Speeds

High-speed trains, like the Shanghai Maglev which travels at over 260 mph, present an immense braking challenge. Relying solely on friction brakes at those speeds would be impractical and would lead to massive wear. These trains use electromagnetic systems as their primary service and emergency brakes. The wear-free operation is essential for maintaining a demanding service schedule, and the powerful braking force is a critical safety feature.

Roller Coasters and Amusement Rides: The Ultimate Safety Net

This is where I first fell in love with the technology. Modern roller coasters use rows of permanent magnet fins to provide highly reliable, repeatable, and maintenance-free braking. They can bring a multi-ton vehicle from over 100 mph to a controlled stop in just a few dozen feet, thousands of times a day, without ever wearing out. It’s the ultimate fail-safe system.

Industrial Machinery and Heavy Vehicles: The Unsung Heroes

In the industrial world, eddy current brakes are workhorses. They are used in dynamometers to test the horsepower of engines, where they can absorb and dissipate thousands of horsepower worth of energy for extended periods. On heavy trucks and buses, they are used as “retarders.” This supplemental braking system saves the primary friction brakes from overheating on long downhill stretches, drastically improving safety and extending the life of the service brakes by as much as ten times.

Fitness Equipment: Your Smooth Workout Partner

Have you ever used a high-end stationary bike or elliptical where you can adjust the resistance electronically with the push of a button? Chances are, you were working against an eddy current brake. The system provides a smooth, quiet, and precisely controllable resistance that you just can’t get from a physical friction pad. This is a perfect example of how the underlying motor principle of using magnetism to create force can be adapted for completely different applications.

Conclusion: The Future of Braking Technology is Electromagnetic

From the silent, powerful stop of a bullet train to the smooth resistance of an exercise bike, the application of eddy currents in braking is a testament to elegant physics put to practical use. What started as a laboratory curiosity with a magnet falling through a pipe has evolved into a cornerstone of modern engineering.

What I find most compelling is that this technology solves the fundamental problem of traditional brakes: wear. By replacing physical contact with an invisible magnetic field, we’ve created systems that are safer, more reliable, and far less costly to maintain over their lifetime.

While they may not replace friction brakes entirely due to their lack of holding power, eddy current brakes have carved out an essential role. As we push for faster trains, more reliable machinery, and safer amusement rides, the importance of this invisible stopping force will only continue to grow. It’s a quiet revolution in how we control motion, and it’s happening all around us.