The Science and Art of Magnet Making: How Are Permanent Magnets Manufactured?

Of course, here is the comprehensive, long-form article based on your instructions.

Table of Contents

- Atomic Structure and Electron Spin

- Magnetic Domains: The Building Blocks of Magnetism

- Curie Temperature: Losing Magnetism

- Coercivity and Remanence: Defining Permanent Magnet Strength

- Magnetic Anisotropy: Directing Magnetism

- Rare Earth Elements

- Traditional Magnetic Alloys

- Sintered Rare-Earth Magnets (e.g., Neodymium Magnets)

- Bonded Rare-Earth Magnets (e.g., Bonded Neodymium)

- Alnico Magnets

- Ferrite (Ceramic) Magnets

Unlocking the Mystery of Permanent Magnetism

I’ll never forget the first time I held a freshly magnetized, high-grade Neodymium magnet. It wasn’t just a piece of metal; it felt alive. It had this invisible, powerful energy that you could feel pushing and pulling against another magnet in your hand. It made me wonder: how do you take a bunch of raw, seemingly inert materials and turn them into something with such a profound and permanent force?

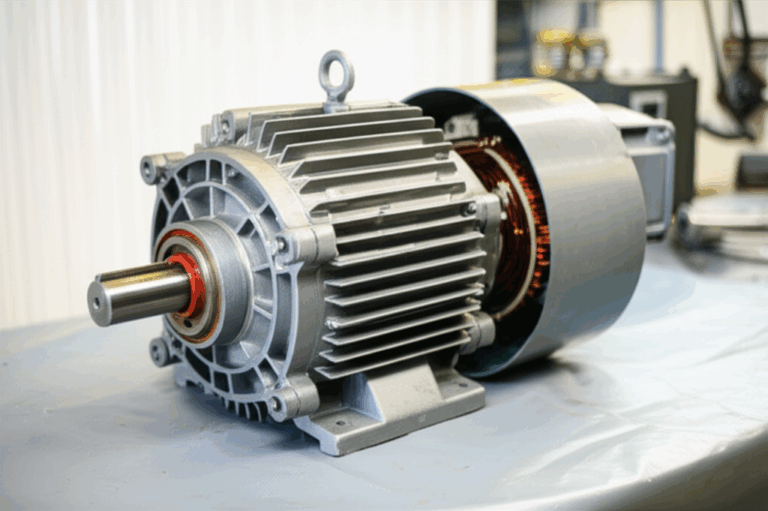

Permanent magnets are the unsung heroes of our modern world. They’re not just for sticking notes to your fridge. They are critical components inside the traction motors of electric vehicles (EVs), the generators of massive wind turbines, the precision sensors in your smartphone, and the speakers that play your favorite music. Without them, much of the technology we rely on simply wouldn’t work.

But understanding how they are made is a journey into a world of incredible science and precision engineering. It’s a process that’s part metallurgy, part physics, and part art. In my years working with these materials, I’ve seen firsthand that creating a powerful, stable permanent magnet is far more complex than just melting some metal and sticking it in a magnetic field. We’re going to pull back the curtain on this intricate process.

The Fundamental Principles Behind Permanent Magnetism

Before we can dive into the nuts and bolts of manufacturing, you need to understand why certain materials can become magnets in the first place. It all starts at the atomic level.

Atomic Structure and Electron Spin

Think of every atom as a tiny solar system. You have the nucleus in the center and electrons spinning around it. Crucially, these electrons also spin on their own axis. This spin creates a minuscule magnetic field, turning each electron into a nano-sized magnet.

In most materials, these electron spins are completely random. For every electron spinning one way, there’s another spinning the opposite way, so their magnetic fields cancel each other out. It’s a chaotic mess. But in a few special materials—like iron, cobalt, and rare earth elements like neodymium—the electrons in their outer shells can align their spins. This is the first ingredient for magnetism.

Magnetic Domains: The Building Blocks of Magnetism

Now, imagine billions of these atoms with aligned spins grouping together. These groups form what we call magnetic domains. You can picture a magnetic domain as a neighborhood where all the individual atomic magnets are pointing in the same direction.

In an unmagnetized piece of iron, however, these domains are still pointing in random directions. One neighborhood points north, another points south, another east, and so on. The overall effect? They cancel each other out, and the material isn’t magnetic. The whole secret to creating a permanent magnet is to get all these domains to point in the same direction—and stay that way.

Curie Temperature: Losing Magnetism

Have you ever wondered if you can “kill” a magnet? You absolutely can, with heat. Every magnetic material has a Curie temperature. If you heat a magnet above this temperature, the atoms gain so much energy that they start vibrating violently. This thermal chaos overwhelms the forces holding the magnetic domains in alignment, and they scramble back into random orientations. The magnetism is gone. For Neodymium magnets, this can happen at surprisingly low temperatures, which is a key consideration in their manufacturing and application.

Coercivity and Remanence: Defining Permanent Magnet Strength

Two words you’ll hear a lot in the magnet industry are remanence and coercivity.

- Remanence (or Magnetic Flux Density) is how much magnetic field a magnet retains after the external magnetizing field is removed. It’s the magnet’s residual strength.

- Coercivity is the magnet’s resistance to being demagnetized by an opposing magnetic field. Think of it as magnetic stubbornness. High coercivity is what makes a permanent magnet permanent.

The goal of the manufacturing process is to maximize both of these properties to create the strongest, most durable magnet possible.

Magnetic Anisotropy: Directing Magnetism

Finally, there’s magnetic anisotropy. This just means the material has a preferred direction of magnetism. During manufacturing, we can encourage the material’s crystal structure to align along a specific axis. This makes it much easier to magnetize the material in that direction and much harder in any other. It’s like giving all the magnetic domains a clear, easy path to follow.

Key Materials Used in Permanent Magnet Production

The “recipe” for a magnet determines its strength, cost, and temperature resistance. There are a few major families of materials we use.

Rare Earth Elements

When you hear about the most powerful magnets, you’re hearing about rare earth magnets. The primary players are:

- Neodymium (Nd), Iron (Fe), and Boron (B): These three form the alloy for Neodymium Magnets (NdFeB), the strongest permanent magnets commercially available. They are the backbone of high-performance applications like EV motors and wind turbines.

- Samarium (Sm) and Cobalt (Co): These are used to make Samarium Cobalt Magnets (SmCo). While not as strong as NdFeB magnets, they have a much higher Curie temperature, making them perfect for high-temperature applications in aerospace and military tech.

- Dysprosium (Dy) and Terbium (Tb): These are “heavy” rare earths added in small amounts to NdFeB magnets. They drastically increase the magnet’s coercivity and resistance to heat, but they are extremely expensive and have a volatile supply chain, which is a huge challenge for the industry.

Traditional Magnetic Alloys

Long before rare earth magnets came along, we relied on other alloys:

- Aluminum (Al), Nickel (Ni), Cobalt (Co), and Iron (Fe): This mix creates Alnico magnets. These are made by casting or sintering and are known for their incredible temperature stability and good corrosion resistance, though their magnetic strength is lower than rare earths.

- Iron (Fe) Oxide, with Barium (Ba) or Strontium (Sr) Carbonate: These ingredients are used to make Ferrite magnets, also known as ceramic magnets. They are the brittle, dark gray magnets you often see. They aren’t very strong, but they are incredibly cheap and have excellent corrosion resistance, making them the most widely produced magnet by volume for things like refrigerator magnets and small DC motors.

General Stages of Permanent Magnet Manufacturing: An Overview

No matter the type, the manufacturing process generally follows a few key stages:

Detailed Manufacturing Processes by Magnet Type

This is where things get really interesting. The specific steps for each magnet type are dramatically different, and I’ve always found the process for sintered Neodymium magnets to be the most fascinating.

1. Sintered Rare-Earth Magnets (e.g., Neodymium Magnets)

This is the high-tech, high-performance route, primarily using powder metallurgy.

2. Bonded Rare-Earth Magnets (e.g., Bonded Neodymium)

Bonded magnets offer a trade-off: they are less powerful than their sintered cousins but can be formed into incredibly complex shapes with tight tolerances, eliminating the need for costly machining.

The process starts similarly, by creating a fine magnetic powder. But instead of pressing and sintering, this powder is mixed with a polymer binder like epoxy or nylon. This magnetic “dough” is then either compression molded (pressed into a mold) or injection molded (injected into a mold, like plastic). The resulting part is durable and precisely shaped. Since it doesn’t go through high-temperature sintering, its magnetic properties are lower, but it’s a fantastic, cost-effective solution for many applications.

3. Alnico Magnets

The manufacturing process for Alnico feels a bit more old-school, often relying on casting.

4. Ferrite (Ceramic) Magnets

Ferrite magnets are made using a ceramic process, which is quite different from the others.

Quality Control and Testing in Magnet Production

From my experience, I can tell you that making a magnet is one thing; making a good magnet consistently is another entirely. Quality control is relentless. We use permeameters to test the magnetic characteristics (the B-H curve) of samples from every batch. We use advanced equipment to check dimensional accuracy down to the micron. Coatings are subjected to salt spray tests to ensure corrosion resistance. Every step is monitored because a small deviation in temperature during sintering or an impurity in the raw materials can ruin an entire batch. The interplay between the different parts, like the stator and rotor, depends on this magnetic consistency for optimal motor performance.

Challenges and Innovations in Permanent Magnet Manufacturing

The world of magnet manufacturing is constantly evolving, driven by some significant challenges.

- Supply Chain Volatility: The heavy reliance on rare earth elements, of which China produces over 80%, creates huge geopolitical and cost risks. I’ve seen the price of Neodymium and Dysprosium swing wildly, making long-term planning a nightmare. This has led to a huge push for innovations that reduce the need for these critical materials. A fantastic example is the Grain Boundary Diffusion (GBD) process, where heavy rare earths like Dysprosium are applied only to the surface of a magnet before heat treatment. They then diffuse into the grain boundaries, boosting coercivity without having to mix these expensive elements into the entire alloy.

- Environmental Impact: Magnet production is energy-intensive. The mining and refining of rare earths can also be environmentally damaging. There’s a growing movement towards recycling permanent magnets from end-of-life products, like hard disk drives and EV motors, and developing more sustainable manufacturing processes.

- Performance Demands: Industries are constantly pushing for smaller, lighter, and more powerful magnets. This drives research into new materials, like iron-nitride magnets, and advanced manufacturing techniques like additive manufacturing (3D printing) of magnets, which could one day allow for the creation of magnets with incredibly complex internal magnetic structures. The quality of materials used in related components, such as high-grade silicon steel laminations, is also critical to achieving these performance gains in motor systems.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Engineered Magnetism

The journey from a pile of metallic dust to a powerful permanent magnet is a testament to human ingenuity. It’s a precise dance of chemistry, physics, and engineering that transforms common and rare elements into materials with an almost magical force. Each step—from the violent chaos of the jet mill to the silent, intense heat of the sintering furnace and the final, powerful jolt of the magnetizer—is carefully controlled to align trillions of atomic-scale domains into a single, unified direction.

The next time you start your electric car or feel the hum of your computer, remember the invisible powerhouses at work. They didn’t just appear; they were forged through a process as fascinating and complex as the technologies they enable. The demand for better, more efficient systems, like those requiring a high-quality bldc stator core, ensures that the science and art of magnet making will continue to push the boundaries of what’s possible.