The Science Behind Permanent Magnets: Understanding What Causes Enduring Magnetism

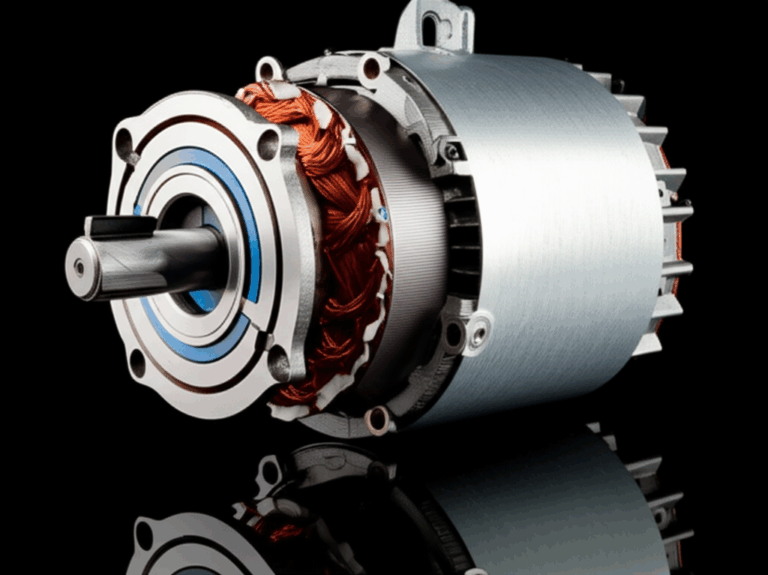

As an engineer or product designer, you constantly work with the consequences of physics. You know that a neodymium magnet will snap to a steel frame with incredible force and that the magnets in a brushless DC motor are fundamental to its operation. But have you ever paused to ask the deeper question: Why? What is it about certain materials that allows them to maintain a powerful magnetic field, seemingly indefinitely, while others don’t?

If you’ve ever found yourself weighing the trade-offs between different magnet grades or trying to understand why a magnet might fail under certain conditions, you’re in the right place. This isn’t just an academic question; it’s a practical one that sits at the very heart of robust engineering design. Understanding the root cause of permanent magnetism empowers you to make smarter material choices, anticipate performance limitations, and have more productive conversations with suppliers.

We’re going to pull back the curtain on this everyday miracle. We’ll travel from the bizarre quantum world of a single electron all the way up to the bulk material properties that define a powerful, lasting magnet.

What We’ll Cover

- The Atomic Origin: A look at how electron spin creates the fundamental building block of magnetism.

- The Prerequisite: Ferromagnetism: Why some materials are special and can exhibit strong magnetic cooperation.

- From Atoms to Bulk Material: Understanding the crucial role of magnetic domains in creating a macroscopic magnet.

- The Making of a Permanent Magnet: Exploring the magnetic “memory” of materials through hysteresis.

- Factors Influencing Magnet Strength: How material composition, manufacturing, and temperature dictate performance.

- Common Types of Permanent Magnets: A practical guide to the properties and causes behind different magnet families.

- Your Engineering Takeaway: A summary of the key principles to empower your design decisions.

The Atomic Origin: Electron Spin and Magnetic Moments

Believe it or not, the story of a massive, powerful permanent magnet begins with one of the smallest things we know: the electron. The cause of magnetism isn’t some mysterious fluid or esoteric force; it’s a fundamental property of matter at the quantum level.

The Fundamental Source: Electrons as Tiny Magnets

Every electron in every atom acts like a minuscule magnet. This magnetism arises from two distinct quantum properties:

So, if every atom is filled with these tiny electron magnets, why isn’t everything magnetic? Why can’t you stick your wooden desk to the refrigerator?

Net Magnetic Moment in Atoms

The answer lies in how electrons are organized within an atom. According to the Pauli Exclusion Principle, electrons typically exist in pairs within their atomic orbitals. When two electrons are paired, they are forced to have opposite spins. One spins “up,” and the other spins “down.”

Imagine placing two small bar magnets side-by-side with their opposite poles touching (North-to-South, South-to-North). Their magnetic fields almost completely cancel each other out. The same thing happens with paired electrons. Their opposing magnetic moments cancel, resulting in a net magnetic moment of zero for that pair.

Permanent magnetism only becomes possible in atoms that have unpaired electrons. These are electrons that occupy an orbital all by themselves. Hund’s rules of electron configuration state that electrons will fill empty orbitals within a subshell before they start pairing up. Elements like iron, nickel, and cobalt are special because their electron configurations leave them with multiple unpaired electrons, each contributing its magnetic moment without being canceled out.

This gives the atom a significant net magnetic moment, turning the entire atom into a tiny, indivisible magnet. But even this isn’t enough to make a material a permanent magnet. You need one more crucial ingredient: cooperation.

The Prerequisite: Ferromagnetism – The Key to Permanence

Having atoms with net magnetic moments is just the first step. To get the powerful effect we see in permanent magnets, these atomic-level magnets need to work together on a massive scale. This cooperative behavior is known as ferromagnetism.

Defining Ferromagnetism: Strong Inter-atomic Interactions

Ferromagnetism is an incredibly strong, quantum mechanical phenomenon where the magnetic moments of adjacent atoms spontaneously align with one another, all pointing in the same direction. Only a few elements—most notably Iron (Fe), Cobalt (Co), Nickel (Ni), and some rare-earth elements like Gadolinium (Gd)—exhibit ferromagnetism at room temperature.

This isn’t a weak attraction; it’s a powerful coupling that locks the atomic moments together. But what causes this “peer pressure” among atoms?

Exchange Interaction: Aligning Electron Spins

The force responsible for this alignment is the exchange interaction. This is a purely quantum mechanical effect with no true classical analogue, but we can think of it as a force that depends on the relative spin orientation of electrons in neighboring atoms.

In ferromagnetic materials, the lowest energy state—the state that matter naturally prefers—occurs when the spins of unpaired electrons in adjacent atoms are aligned in parallel. The exchange interaction makes it energetically favorable for them to all point the same way. This creates a powerful, long-range magnetic order throughout a region of the material.

To put this in perspective, let’s briefly look at other types of magnetism:

- Paramagnetism: In materials like aluminum or platinum, atoms have unpaired electrons, but the exchange interaction is too weak to cause spontaneous alignment. Their atomic moments point in random directions. They are weakly attracted to an external magnetic field, but the moment you remove the field, thermal energy randomizes them again. They have no “memory.”

- Diamagnetism: Materials like copper, gold, and water have no unpaired electrons. They are weakly repelled by a magnetic field. This effect is present in all materials but is so faint that it’s only noticeable in the absence of other types of magnetism.

Ferromagnetism is the only one that has the strong cooperative alignment needed to create a permanent magnet.

From Atoms to Bulk Material: The Role of Magnetic Domains

So, we have atoms with net magnetic moments, and the exchange interaction is forcing them to align. You’d think that any chunk of iron would just be a magnet straight from the factory. But that’s not the case. A common iron nail isn’t a magnet until you make it one.

Why? The answer lies in the concept of magnetic domains.

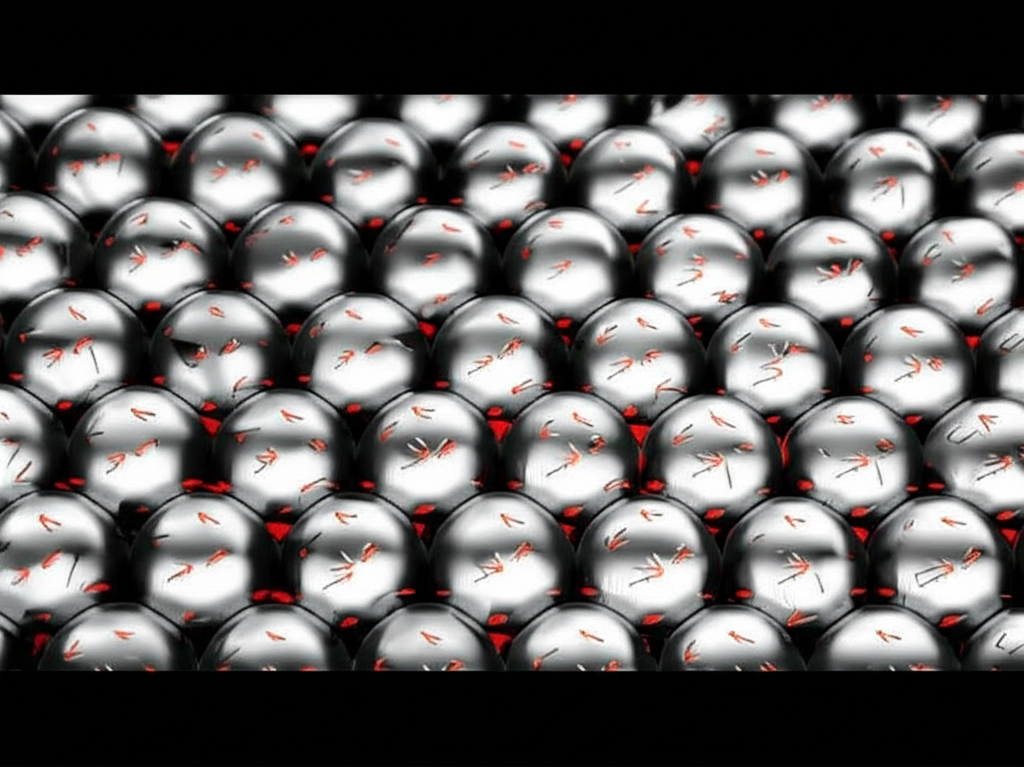

Introduction to Magnetic Domains (Weiss Domains)

Even with the powerful exchange interaction, it’s not energetically favorable for a whole piece of iron to have all of its trillions of atoms pointing in one direction. A massive, single magnetic pole would create a huge external magnetic field, which stores a lot of energy. Nature, being efficient, prefers to find a lower-energy configuration.

It does this by breaking the material up into microscopic regions called magnetic domains (also known as Weiss domains, after physicist Pierre-Ernest Weiss).

Think of it like this: Imagine a country where the law says everyone must face the same direction. But to avoid creating one giant unified front, the country is divided into self-contained provinces. Within each province, everyone dutifully points in the same direction. However, each province is oriented randomly relative to its neighbors—one points north, the next points west, another southeast, and so on.

From the outside, the country appears to have no overall direction. The net effect is zero. This is exactly what an unmagnetized piece of ferromagnetic material looks like. Each magnetic domain is a region where millions of atomic moments are perfectly aligned, creating a fully saturated microscopic magnet. But because the domains themselves are randomly oriented, their magnetic fields cancel each other out on a macroscopic scale.

The boundaries between these regions are called domain walls. These are narrow transition zones where the direction of magnetization gradually shifts from the orientation of one domain to that of its neighbor.

The Magnetization Process: Aligning the Domains

So how do we turn that unmagnetized nail into a magnet? We have to force those randomly oriented domains to align. We do this by applying a strong external magnetic field. This process happens in a few stages:

When you remove the external field, some of that alignment remains. The material’s internal structure and properties will determine just how much alignment is retained, and how difficult it is to undo. This is what separates a temporary magnet from a permanent one.

The Making of a Permanent Magnet: Hysteresis and Material Properties

The ability of a material to retain its magnetism and resist demagnetization is the essence of a permanent magnet. We can visualize this magnetic “memory” using a tool called a hysteresis loop. This graph shows the relationship between the applied external magnetic field strength (H) and the resulting internal magnetic flux density (B) of the material.

The Hysteresis Loop: A Material’s Magnetic “Memory”

Imagine starting with an unmagnetized piece of material (Point 0). As we apply and manipulate an external magnetic field, we trace out a loop:

- Magnetization Curve (0 to Saturation): As we apply an external field (H), the material’s internal magnetism (B) increases as the domains align. Eventually, we reach magnetic saturation.

- Remanence (Br): Now, we reduce the external field back to zero. The internal magnetism doesn’t drop back to zero. It follows a different path. The amount of magnetism left over in the material with no external field applied is called remanence. This is the retained magnetism, the “permanent” part of the magnet.

- Coercivity (Hci): To get the material back to zero magnetism, we have to apply a magnetic field in the opposite direction. The amount of reverse field required to completely demagnetize the material is called coercivity. Think of coercivity as the material’s “stubbornness” or its resistance to being demagnetized.

Materials intended for permanent magnets are engineered to have a wide, “fat” hysteresis loop, signifying both high remanence and high coercivity. In contrast, soft magnetic materials used in applications like transformer cores or silicon steel laminations are designed to have a very “skinny” loop, meaning they magnetize and demagnetize easily with minimal energy loss.

Crucial Properties for Permanent Magnetism

Three key metrics derived from the hysteresis loop define the quality of a permanent magnet:

Magnetic Anisotropy: Directional Preference

What gives a material this high coercivity—this magnetic stubbornness? The key is magnetic anisotropy, which is the property of a material to have a preferred direction of magnetization, often called the “easy axis.” By creating strong anisotropy, engineers can effectively “pin” the magnetic domains in their aligned position, making it very difficult for them to rotate back to a random orientation. This is achieved in several ways:

- Magnetocrystalline Anisotropy: The material’s crystal lattice structure itself has directions along which it is easier to magnetize. In neodymium magnets, the tetragonal crystal structure creates an extremely strong preference along one axis.

- Shape Anisotropy: A long, thin magnetic particle (like a tiny needle) prefers to be magnetized along its longest axis. This principle is used in Alnico magnets.

- Stress Anisotropy: Applying mechanical stress to a material during manufacturing can also induce a preferred direction of magnetization.

Factors Influencing Permanent Magnet Strength and Stability

The theoretical properties described above are brought to life through careful material science and manufacturing. The difference between a weak iron magnet and a powerful rare-earth magnet comes down to three things: what it’s made of, how it’s structured, and how it’s treated.

Material Composition and Alloying

The choice of elements is paramount. The powerful exchange interaction in iron provides high magnetic saturation (leading to high remanence), while rare-earth elements like neodymium and samarium are added for their incredible magnetocrystalline anisotropy, which provides sky-high coercivity. Boron is added to neodymium-iron to stabilize the specific crystal structure needed for these properties to emerge.

Crystal Structure and Microstructure

It’s not enough to just have the right elements. Their microscopic structure (microstructure) is critical. During manufacturing processes like sintering, powders are pressed and heated to form a solid with a specific grain structure. For the highest-grade magnets, this is done in the presence of a strong magnetic field to ensure the crystal grains are all physically oriented in the same direction, maximizing the anisotropic effect. Pinning sites, such as grain boundaries or impurities, are controlled to impede domain wall movement, further increasing coercivity.

Temperature Effects: The Curie Temperature

Heat is the arch-nemesis of magnetism. As you heat a magnet, you introduce thermal energy, which causes the atoms to vibrate more and more violently. This vibration disrupts the orderly alignment of the magnetic domains.

Eventually, you reach a critical point called the Curie Temperature (Tc). At this temperature, the thermal energy completely overcomes the exchange interaction. The material loses its ferromagnetic properties and becomes merely paramagnetic. The long-range magnetic order is destroyed, and the magnet is permanently and irreversibly demagnetized.

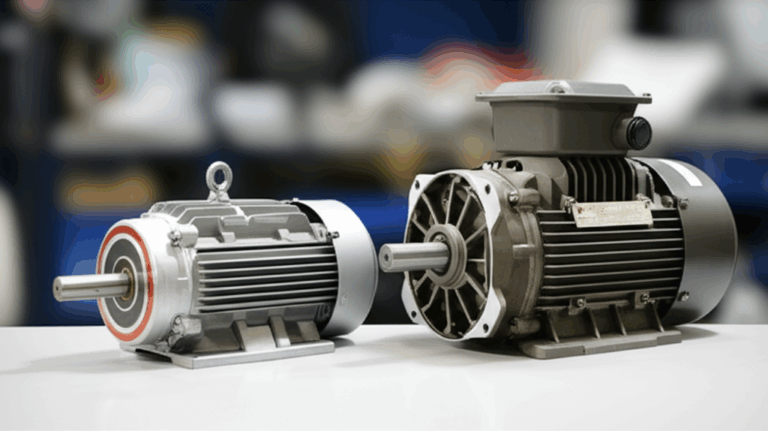

Even well below the Curie temperature, high operating temperatures can cause a magnet to lose some of its strength. This is a critical design consideration, especially in applications like electric motors and generators.

Common Types of Permanent Magnets and Their Causes

The interplay of these factors gives us the families of permanent magnets we use today, each with a unique set of properties rooted in its physics.

| Property | Neodymium (NdFeB) | Samarium-Cobalt (SmCo) | Alnico | Ferrite/Ceramic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Magnetic Cause | Strong exchange interaction (Fe) and extreme magnetocrystalline anisotropy (Nd). | High magnetocrystalline anisotropy and excellent thermal stability from the Sm-Co lattice. | Shape anisotropy of precipitated Fe-Co particles within a non-magnetic matrix. | Magnetocrystalline anisotropy from its hexagonal crystal structure. |

| Key Advantage(s) | Highest strength and energy density. | High-temperature stability, good corrosion resistance. | Excellent temperature stability, high remanence. | Low cost, good corrosion resistance. |

| Disadvantage(s) | Low operating temperature, prone to corrosion. | Higher cost, brittle. | Low coercivity (easy to demagnetize). | Low energy product, brittle. |

- Neodymium Magnets (NdFeB): The champions of strength. Their power is caused directly by the combination of iron’s high saturation and the Nd2Fe14B crystal structure’s massive anisotropy. They are essential in high-performance applications like EV motors, wind turbines, and hard disk drives.

- Samarium-Cobalt Magnets (SmCo): The high-temperature specialists. Their higher Curie temperature makes them the go-to choice for aerospace, military, and industrial applications where thermal stability is more important than raw power.

- Alnico Magnets: A classic design whose permanence is caused by shape anisotropy. During heat treatment, tiny needles of a highly magnetic Fe-Co phase precipitate out. These elongated particles strongly resist being magnetized any way but along their length, giving Alnico its good remanence and excellent temperature stability.

- Ferrite (Ceramic) Magnets: The economical workhorses. Made from iron oxide and barium or strontium carbonate, their magnetism is caused by the magnetocrystalline anisotropy of their hexagonal (“magnetoplumbite”) structure. While not as strong as rare-earth magnets, their low cost and excellent resistance to corrosion make them ubiquitous in everyday applications like refrigerator magnets, speakers, and small DC motors, such as a bldc stator core.

Your Engineering Takeaway: The Interplay of Quantum Physics and Material Science

The seemingly simple force of a permanent magnet is the result of an incredible chain of physical phenomena, scaling all the way from the quantum realm to macroscopic engineering.

Here’s what to remember:

- It Starts with Electron Spin: The fundamental source of magnetism is the intrinsic magnetic moment of unpaired electrons.

- Ferromagnetism is Key: The quantum mechanical exchange interaction forces these atomic moments to align cooperatively, creating strong magnetism.

- Domains Bridge the Gap: A material is divided into microscopic magnetic domains. Magnetization is the process of aligning these domains with an external field.

- Hysteresis Defines Permanence: A material’s ability to retain magnetism (remanence) and resist demagnetization (coercivity) is what makes it a permanent magnet. These properties are locked in by controlling the material’s anisotropy and microstructure.

- Temperature is the Enemy: All permanent magnets will lose their magnetism if heated past their Curie temperature, a critical design limitation.

Understanding these root causes doesn’t just satisfy curiosity—it makes you a better engineer. It allows you to appreciate why a high-coercivity SmCo magnet is needed for a high-temperature sensor, why an NdFeB magnet needs a protective coating, and why a specific manufacturing process is essential for achieving peak performance. This knowledge empowers you to select the right material, design more robust systems, and engage with suppliers on a deeper, more technical level.