Unlocking the Power: What Are the Key Properties of Permanent Magnets?

Over my years working on everything from custom electric motors to intricate sensor assemblies, I’ve learned a crucial lesson the hard way: not all magnets are created equal. I once spent weeks designing a compact, high-power prototype, only to watch it fail spectacularly because the magnet I chose couldn’t handle the operating temperature. It was a frustrating, expensive mistake, but it taught me that understanding the fundamental properties of permanent magnets isn’t just academic—it’s the bedrock of successful engineering and design.

Thinking of a magnet just as “strong” or “weak” is like describing a car by only saying it’s “fast” or “slow.” It misses the whole picture. Is it fast off the line? Can it maintain that speed? Does it overheat? How much power does it pack for its size?

In this guide, I’m going to walk you through the key properties of permanent magnets, breaking them down in a way that I wish someone had for me when I started. We’ll go beyond simple definitions and look at what these characteristics actually mean for your project.

Table of Contents

- What Are the Properties of Permanent Magnets?

- Introduction to Permanent Magnets

- Fundamental Magnetic Properties

- Remanence (Br) – The Residual Magnetism

- Coercivity (Hcj or Hc) – Resistance to Demagnetization

- Maximum Energy Product (BHmax) – The Magnet’s “Working Power”

- Curie Temperature (Tc) – The Point of Demagnetization

- Maximum Operating Temperature (Tmax) – Practical Heat Limit

- Other Important Characteristics

- Physical and Mechanical Properties

- Magnetic Anisotropy – Directional Preference

- Temperature Coefficients – Performance Over Temperature

- Reversible vs. Irreversible Losses

- How Properties Vary Across Magnet Types

- Neodymium (NdFeB) Magnets

- Samarium Cobalt (SmCo) Magnets

- Alnico Magnets

- Ferrite (Ceramic) Magnets

- Factors Influencing Permanent Magnet Properties

- Conclusion: Understanding Properties for Optimal Application

Introduction to Permanent Magnets

At their core, permanent magnets are materials that generate their own persistent magnetic field without needing an external power source. Think of them as tiny, self-contained sources of invisible force. This ability is what makes them foundational components in thousands of technologies we use every day, from the motors that power electric vehicles to the sensors in your phone and the hard drives that store your data.

But what gives a magnet its specific personality—its strength, its heat tolerance, its resistance to being “turned off”? It all comes down to a handful of core properties. Let’s dive in.

Fundamental Magnetic Properties

When you look at a magnet’s data sheet, you’ll see a bunch of symbols and numbers. At first, it can look like alphabet soup. But once you know what they mean, you can predict exactly how that magnet will behave. Here are the “big four” you absolutely need to know.

Remanence (Br) – The Residual Magnetism

- What it is: Remanence, symbolized as Br, is the measure of the magnetic flux density left in a magnet after the external magnetizing field is removed.

- What it really means: In simple terms, Br tells you the raw, inherent strength of the magnet. If you were to stick a magnet to a fridge, the force holding it there is a direct result of its remanence. It’s the baseline strength of the magnet when it’s just sitting there, doing its job.

- Units: You’ll typically see this measured in Tesla (T) or Gauss (G). One Tesla equals 10,000 Gauss. So, a magnet with a Br of 1.2 T is the same as one with 12,000 Gauss.

For applications like holding, lifting, or magnetic separation, a high remanence is often the top priority. You want the strongest possible magnetic field in a given space, and Br is your first indicator of that.

Coercivity (Hcj or Hc) – Resistance to Demagnetization

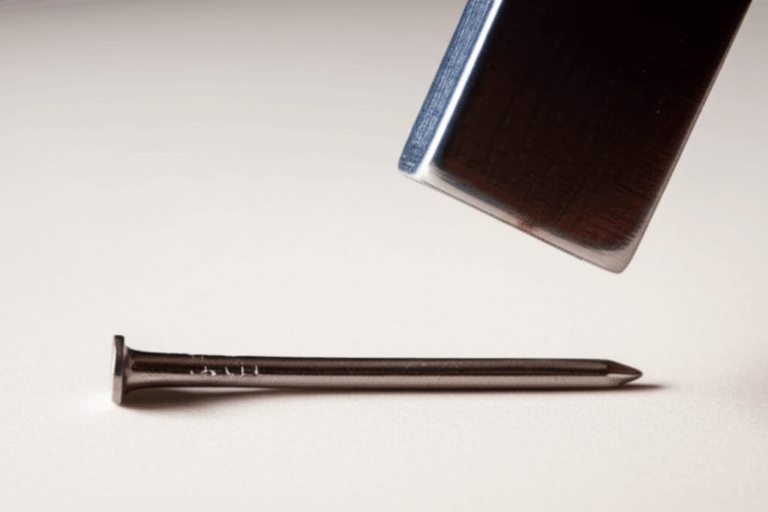

- What it is: Coercivity (Hcj) is the measure of a magnet’s resistance to being demagnetized by an external magnetic field.

- What it really means: This is all about toughness. Think of coercivity as the magnet’s stubbornness. A magnet with high coercivity can withstand strong opposing magnetic fields, high temperatures, and physical shock without losing its magnetism. It’s a measure of magnetic stability. A low-coercivity magnet, on the other hand, can be easily weakened or even completely demagnetized.

- Units: Coercivity is measured in kiloAmpere per meter (kA/m) or kiloOersted (kOe).

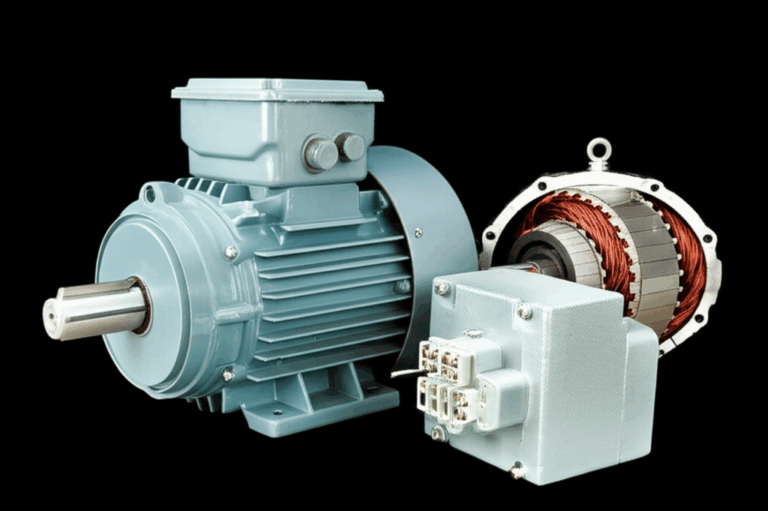

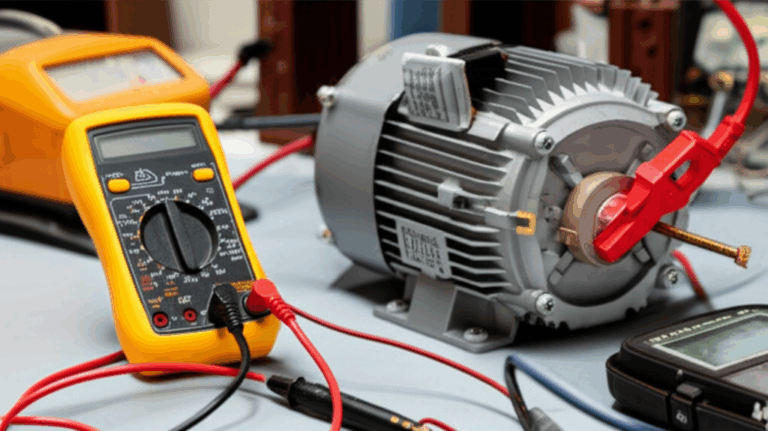

In my experience, this is a property that people often overlook until it’s too late. It’s especially critical in applications like electric motors, where the magnet is constantly exposed to changing and opposing magnetic fields generated by the coils. For instance, the performance of a high-speed motor relies heavily on the relationship between the permanent magnets and the surrounding coils, which essentially make up the stator and rotor. A magnet with low coercivity would quickly weaken in that environment, leading to a catastrophic loss of performance.

Maximum Energy Product (BHmax) – The Magnet’s “Working Power”

- What it is: The Maximum Energy Product (BHmax) represents the point on the magnet’s demagnetization curve where the product of magnetic flux density (B) and magnetic field strength (H) is at its maximum.

- What it really means: This is the single best indicator of a magnet’s overall performance. If remanence (Br) is the magnet’s raw strength and coercivity (Hc) is its toughness, then BHmax is the total “power” it can deliver for its size. A magnet with a high BHmax can produce a strong magnetic field in a small package. It’s a measure of efficiency.

- Units: You’ll see this expressed in kilojoules per cubic meter (kJ/m³) or MegaGauss Oersted (MGOe).

When I was working on that EV motor prototype, BHmax was my holy grail. We needed to generate as much torque as possible in the smallest, lightest motor we could build. That meant we needed a magnet with the highest possible energy product. A higher BHmax allows for miniaturization and improved efficiency, which is why Neodymium magnets, with their incredibly high BHmax values, are the kings of modern high-performance applications.

Curie Temperature (Tc) – The Point of Demagnetization

- What it is: The Curie Temperature is the specific temperature at which a magnet permanently loses its magnetic properties and becomes paramagnetic (no longer a magnet).

- What it really means: This is the magnet’s self-destruct temperature. Once you heat a magnet past its Curie point, it’s game over. Even after it cools down, it won’t be a magnet anymore unless you re-magnetize it. It’s an absolute upper limit that you must never exceed.

Think of it like the melting point of ice. Once you go past 0°C (32°F), it’s no longer ice; it’s water. Similarly, once you go past the Curie Temperature, it’s no longer a permanent magnet.

Maximum Operating Temperature (Tmax) – Practical Heat Limit

- What it is: The Maximum Operating Temperature is the highest temperature at which a magnet can be used continuously without suffering significant, irreversible loss of its magnetism.

- What it really means: This is the number you should care about for practical design. While the Curie Temperature is the point of no return, Tmax is the safe, practical limit. Exceeding Tmax won’t instantly destroy the magnet, but it will cause it to permanently lose some of its strength. The hotter you go past Tmax, the more strength it will lose for good.

This was the property that bit me in my early prototype. I chose a standard-grade Neodymium magnet with a Tmax of 80°C. Under load, my motor was hitting 100°C. The magnet didn’t die completely, but it lost about 15% of its strength permanently, and the motor’s performance tanked. Lesson learned: always design with a healthy safety margin below Tmax.

Other Important Characteristics

Beyond the big four, there are other characteristics that can be just as important depending on your application. I’ve learned to consider these as part of a complete picture.

Physical and Mechanical Properties

Magnets aren’t just magnetic; they’re also physical objects. Their mechanical properties matter a great deal.

- Brittleness: Most high-performance magnets, like Neodymium and Samarium Cobalt, are very brittle. They behave more like ceramics than metals. I’ve seen them chip, crack, or even shatter if they’re dropped or allowed to snap together uncontrollably. Alnico, on the other hand, is much more ductile and can be machined more easily.

- Corrosion Resistance: This is a huge one. Neodymium magnets, for all their strength, are notoriously prone to corrosion—they rust easily. That’s why they almost always come with a protective coating (like nickel, zinc, or epoxy). In a humid or harsh environment, an uncoated NdFeB magnet will crumble into dust. Ferrite and Alnico magnets, however, have excellent corrosion resistance and often don’t need any coating.

- Density: The weight of the magnet can be critical in applications like aerospace or portable electronics.

Magnetic Anisotropy – Directional Preference

Most modern magnets are anisotropic, which means they have a preferred direction of magnetization. During the manufacturing process, a powerful magnetic field is applied to align the material’s crystalline structure. This makes the magnet much stronger along that specific “axis of orientation.” If you try to magnetize it in any other direction, it will be significantly weaker.

Isotropic magnets, like some bonded or cast Alnico types, have no preferred direction and can be magnetized along any axis. They are weaker overall but offer more flexibility in some applications. For nearly all high-performance uses, I exclusively work with anisotropic magnets to get the most magnetic force for the size.

Temperature Coefficients – Performance Over Temperature

This tells you how much a magnet’s properties change as the temperature fluctuates. You’ll usually see two values: one for remanence (Br) and one for coercivity (Hcj). They are expressed as a percentage change per degree Celsius (%/°C).

A negative temperature coefficient for Br (which is typical) means the magnet gets slightly weaker as it gets hotter and slightly stronger as it gets colder. For coercivity, the change can be more dramatic. Understanding these coefficients is vital for designing systems that need to perform consistently across a wide temperature range.

Reversible vs. Irreversible Losses

This is tied to the temperature coefficients and Tmax.

- Reversible Loss: This is a temporary drop in magnetic strength when a magnet is heated. As long as you stay below the maximum operating temperature, the magnet will regain its full strength when it cools back down.

- Irreversible Loss: This is a permanent loss of strength that occurs when a magnet is heated beyond its Tmax or exposed to a strong demagnetizing field. The only way to restore this lost strength is to completely re-magnetize the material.

How Properties Vary Across Magnet Types

The real magic happens when you see how these properties combine in different magnet materials. There is no single “best” magnet—the right choice is always a trade-off.

Neodymium (NdFeB) Magnets

- The Powerhouse: These are the strongest permanent magnets commercially available, boasting the highest Br and BHmax by a long shot.

- My Experience: Whenever a project demands maximum power in a minimal space, NdFeB is my first choice. They are essential for high-performance applications like EV motors, wind turbine generators, and high-fidelity headphones. For instance, in a brushless DC motor, a powerful NdFeB magnet allows for a more compact and efficient bldc stator core design.

- The Downsides: They have a relatively low maximum operating temperature (starting around 80°C for standard grades), are very brittle, and will rust away without a protective coating.

Samarium Cobalt (SmCo) Magnets

- The High-Temp Champion: SmCo magnets are the second strongest type but their real advantage is their exceptional performance at high temperatures. They have a very high Tmax and Curie Temperature.

- My Experience: When I’m designing something for a harsh, high-temperature environment—like military, aerospace, or downhole drilling sensors—SmCo is the go-to material. They are also highly resistant to corrosion.

- The Downsides: They are expensive and just as brittle as Neodymium magnets.

Alnico Magnets

- The Temperature Veteran: Alnico magnets have the best thermal stability of all. They can operate at incredibly high temperatures (up to 550°C) and have an extremely high Curie Temperature.

- My Experience: Before rare-earth magnets came along, Alnico was king. Today, I use them in applications like high-temperature sensors, guitar pickups, and some types of meters where extreme temperature stability is more important than raw power. The historical significance of Alnico is tied to the very foundation of how we understand the motor principle in many classic designs.

- The Downsides: Their biggest weakness is a very low coercivity, meaning they can be easily demagnetized by external fields. They are also relatively low in terms of energy product compared to rare-earths.

Ferrite (Ceramic) Magnets

- The Workhorse: You’ve seen these everywhere—they are the black magnets on your refrigerator. Ferrite magnets have lower magnetic strength (low Br and BHmax).

- My Experience: What they lack in strength, they make up for in other areas. They are incredibly low-cost, have good coercivity (resisting demagnetization), and boast fantastic corrosion resistance. I use them in countless cost-sensitive applications like affordable DC motors, loudspeakers, and magnetic separators.

- The Downsides: They are brittle and have much lower strength than rare-earth magnets.

Factors Influencing Permanent Magnet Properties

A magnet’s final properties aren’t just a result of its chemical formula. Several factors come into play:

- Material Composition: Tiny changes in the alloy, like adding dysprosium to Neodymium magnets, can dramatically improve their coercivity and temperature resistance.

- Manufacturing Process: Whether a magnet is sintered (powdered metal fused with heat), cast (molten metal poured into a mold), or bonded (magnetic powder mixed with a polymer binder) has a huge impact on its final properties. The processes used to create components that work with magnets, such as producing high-quality electrical steel laminations, are equally crucial for the performance of the entire magnetic circuit.

- External Factors: Exposure to strong opposing magnetic fields, extreme temperatures (hot or cold), and even radiation can alter a magnet’s properties over time.

Conclusion: Understanding Properties for Optimal Application

As I learned from my own early mistakes, choosing the right magnet is a balancing act. You can’t just pick the one with the highest BHmax and call it a day. You have to look at the entire picture.

- Do you need raw strength? Look at Remanence (Br) and Energy Product (BHmax).

- Will the magnet face opposing fields or high heat? Coercivity (Hcj) and Maximum Operating Temperature (Tmax) are your most important metrics.

- Is it for a high-temperature furnace sensor or a cryogenic application? Check the Curie Temperature and Temperature Coefficients.

- Will it be exposed to moisture or rough handling? Consider corrosion resistance and brittleness.

- And finally, what’s your budget?

By taking the time to understand these core properties, you move from simply picking a magnet to strategically selecting a critical engineering component. It’s the difference between a project that works and one that excels.