Unraveling the Pure Motor Cranial Nerves: A Definitive Guide

Of course. Here is the article you requested.

Table of Contents

- The Quick Answer You’re Looking For

- Why This Distinction Matters

- Cranial Nerve III: The Oculomotor Nerve – The Master of Eye Movement

- Cranial Nerve IV: The Trochlear Nerve – The Eye’s Downward Gaze Specialist

- Cranial Nerve VI: The Abducens Nerve – The Side-Eye Commander

- Cranial Nerve XI: The Spinal Accessory Nerve – The Shoulder Shrugger

- Cranial Nerve XII: The Hypoglossal Nerve – The Tongue’s Conductor

- What Defines a “Motor Only” Nerve?

- A Quick Look at Sensory Cranial Nerves

- Understanding the “Jack-of-all-Trades”: Mixed Cranial Nerves

- My Favorite Mnemonic for Remembering Nerve Types

- Why This Classification is a Clinician’s Best Friend

- Common Conditions Affecting Pure Motor Nerves

- Are there any other pure motor cranial nerves?

- What’s a good mnemonic just for the pure motor nerves?

- How are pure motor nerves tested in a clinical setting?

- What really distinguishes CN III, IV, and VI?

Which Cranial Nerves Carry Only Motor Information?

When I first started diving into neuroanatomy, the twelve cranial nerves felt like a secret society. Each had a number, a strange name, and a list of functions that seemed impossible to memorize. The question that always popped up on quizzes was, “Which of the following cranial nerves carries only motor information?” It seemed like a simple piece of trivia, but I quickly learned it’s one of the most fundamental concepts for understanding how our brain communicates with our body.

So, let’s get straight to it.

The Quick Answer You’re Looking For

There are five cranial nerves that are classified as purely motor. They are:

- Cranial Nerve III (Oculomotor Nerve)

- Cranial Nerve IV (Trochlear Nerve)

- Cranial Nerve VI (Abducens Nerve)

- Cranial Nerve XI (Spinal Accessory Nerve)

- Cranial Nerve XII (Hypoglossal Nerve)

That’s it. If you’re studying for a test and need the fast answer, memorize that list: III, IV, VI, XI, and XII. These five nerves are the dedicated action-takers of the cranial nerve world. They are all about sending commands out from the brain to make muscles move.

Why This Distinction Matters

You might be wondering, “Okay, so what? Why does it matter if a nerve is motor, sensory, or both?” In my experience, understanding this classification is the difference between simply memorizing facts and truly understanding the nervous system’s logic.

Think of your nervous system as a complex electrical grid. “Motor information” consists of outgoing signals, or efferent signals, that travel from your central nervous system (CNS) to the muscles and glands, telling them what to do. It’s the “go” signal. “Sensory information,” on the other hand, is the incoming data—the afferent signals—that your body sends back to the brain, reporting on what’s happening. It’s the “what we feel” signal.

A pure motor nerve is like a one-way street, dedicated exclusively to delivering commands for movement. Knowing which nerves are one-way streets is incredibly useful, especially in a clinical setting. If a patient can’t move their eye outward, a doctor can immediately suspect an issue with a specific pure motor nerve—the Abducens nerve (CN VI). It helps them narrow down the problem with incredible precision.

The Five Pure Motor Cranial Nerves Explained

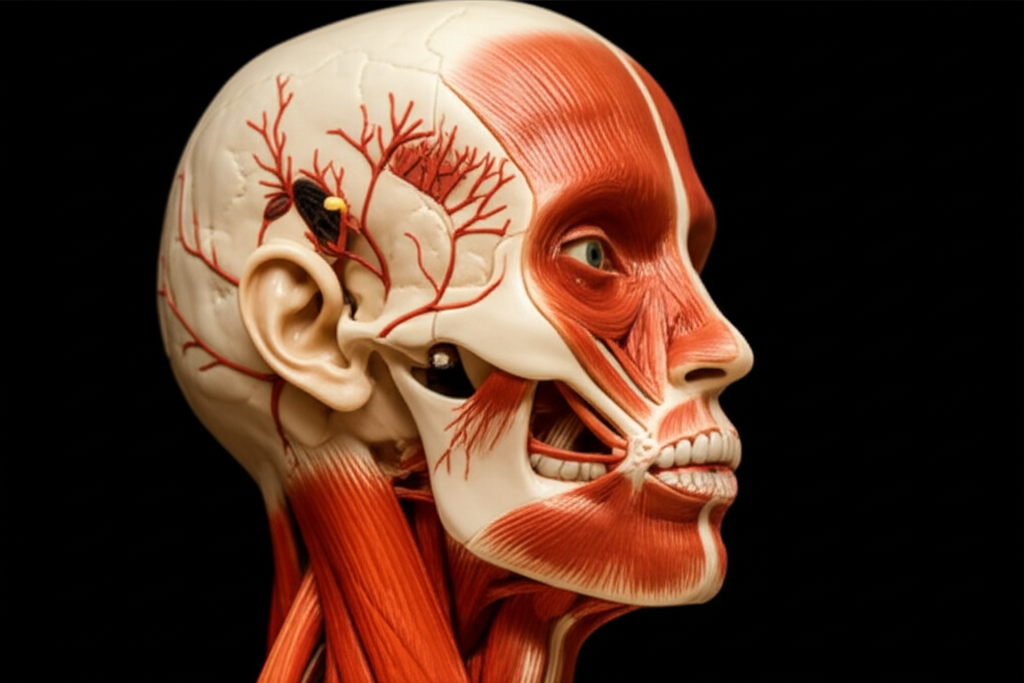

Let’s break down this exclusive club of five nerves. I remember finally grasping their roles when I stopped trying to memorize their names and started visualizing what each one does.

Cranial Nerve III: The Oculomotor Nerve – The Master of Eye Movement

I think of the Oculomotor nerve as the workhorse of eye movement. Its name literally means “eye mover,” and it does the lion’s share of the work.

- Primary Function: CN III controls four of the six extraocular muscles that move your eyeball: the superior, inferior, and medial recti, and the inferior oblique. This allows you to look up, down, and inward toward your nose.

- Secondary Functions: It also does two other crucial jobs. It controls the levator palpebrae superioris muscle, which lifts your eyelid. Without it, you’d have a droopy eyelid, a condition called ptosis. Additionally, it carries parasympathetic fibers that constrict your pupil in bright light and change the shape of your lens for focusing.

My takeaway for remembering it: When I see “Oculomotor,” I think “most of the motion.” It handles almost everything your eye does, from looking around to keeping the lid open. A problem with CN III is dramatic; the eye often drifts “down and out,” the eyelid droops, and the pupil is dilated.

Cranial Nerve IV: The Trochlear Nerve – The Eye’s Downward Gaze Specialist

The Trochlear nerve is a bit of an oddball, but it has a very specific and elegant job. It’s the smallest cranial nerve and has the longest intracranial path. It’s also the only one that exits from the back (dorsal side) of the brainstem.

- Primary Function: CN IV innervates just one muscle: the superior oblique. This muscle works like a pulley system (the trochlea is Latin for “pulley”) to move the eye downward and inward.

- Clinical Relevance: When I was learning about this, a mentor told me to think of the “stair-walking nerve.” People with Trochlear nerve palsy often have trouble looking down to walk down stairs and may see double (vertical diplopia). To compensate, they often tilt their head away from the affected side. It’s a subtle but classic sign.

My takeaway for remembering it: “IV for SO,” meaning Cranial Nerve IV for the Superior Oblique muscle. It’s a specialist with one job: helping you look down and in.

Cranial Nerve VI: The Abducens Nerve – The Side-Eye Commander

The Abducens nerve also has a single, clear-cut function, making it relatively easy to remember.

- Primary Function: CN VI controls the lateral rectus muscle. This muscle’s sole purpose is to pull the eye outward, away from the midline. The movement is called abduction—hence the name “Abducens.”

- Clinical Relevance: Damage to the Abducens nerve is the most common isolated eye muscle palsy. A patient with this issue can’t look to the side with the affected eye. Their eye may drift inward, causing horizontal double vision that gets worse when they try to look sideways.

My takeaway for remembering it: I link the “ab” in Abducens to “abduct,” meaning to move away from the body. CN VI moves the eye away from the nose. It’s the nerve that lets you give someone the side-eye.

Cranial Nerve XI: The Spinal Accessory Nerve – The Shoulder Shrugger

This nerve is unique because it has roots in both the brainstem (cranial root) and the spinal cord (spinal root). However, it’s primarily considered a motor nerve.

- Primary Function: The Spinal Accessory nerve innervates two major muscles in the neck and shoulders: the sternocleidomastoid and the trapezius.

- The sternocleidomastoid helps you turn your head to the opposite side.

- The trapezius allows you to elevate your shoulders (shrug) and stabilize your scapula.

- Clinical Relevance: Because of its long, superficial path in the neck, CN XI is vulnerable to injury during surgeries like lymph node biopsies. When I was shadowing in a clinic, I saw a patient with a damaged accessory nerve. They had a “winged” scapula and a noticeable shoulder droop; they couldn’t shrug their shoulder on that side effectively. It was a powerful lesson in anatomy’s real-world impact.

My takeaway for remembering it: I just think of the number 11 as two shoulders. “Eleven shrugs.” It controls turning your head and shrugging your shoulders. Simple.

Cranial Nerve XII: The Hypoglossal Nerve – The Tongue’s Conductor

The last of our pure motor nerves, the Hypoglossal, is all about the tongue. Its name means “under the tongue.”

- Primary Function: CN XII provides motor control to all the intrinsic muscles (which change the tongue’s shape) and most of the extrinsic muscles (which move the tongue’s position) of the tongue.

- Clinical Relevance: This nerve is essential for clear speech (articulation) and swallowing (deglutition). When there’s a lesion, it causes predictable symptoms. To test it, a doctor will ask the patient to stick out their tongue. If there’s a problem with the right Hypoglossal nerve, the tongue will deviate to the right side. The saying I learned is “you lick your wounds,” meaning the tongue points toward the side of the lesion. You may also see muscle wasting (atrophy) and small twitches (fasciculations) on the affected side.

My takeaway for remembering it: “Hypoglossal” sounds complex, but its function is straightforward. It’s the tongue nerve. Everything from speaking to eating depends on it.

Differentiating Cranial Nerves: Motor, Sensory, and Mixed Functions

To really appreciate why our five pure motor nerves are special, you have to understand the other categories. It’s like learning about the roles on a football team; knowing the quarterback’s job is more meaningful when you also know what the linemen and receivers do.

What Defines a “Motor Only” Nerve?

As we’ve discussed, a pure motor nerve is a one-way communication line. It carries efferent nerve fibers, which are signals moving away from the central nervous system to a target muscle or gland. These are the command-and-control pathways. When a nerve is “purely motor,” it means it doesn’t have any fibers dedicated to sending sensory information back to the brain.

It’s like a simple light switch. The switch (brain) sends a command (electricity) down the wire (nerve) to the bulb (muscle), and the bulb lights up (contracts). There’s no information flowing back up that same wire. This concept is fundamental to the motor principle, where a signal directly causes a mechanical action.

A Quick Look at Sensory Cranial Nerves

In contrast, pure sensory nerves are the body’s data collectors. They only contain afferent fibers, carrying information toward the brain. They are responsible for our special senses. There are three of them:

- Cranial Nerve I (Olfactory): The nerve for smell.

- Cranial Nerve II (Optic): The nerve for vision.

- Cranial Nerve VIII (Vestibulocochlear): The nerve for hearing and balance.

These nerves don’t make anything move; they just report on the world.

Understanding the “Jack-of-all-Trades”: Mixed Nerves

The final group is the mixed nerves. These are the multitasking superstars of the nervous system. They are two-way superhighways, containing both motor (efferent) and sensory (afferent) fibers. They carry commands out and bring information back in, all within the same nerve bundle.

There are four mixed cranial nerves:

- Cranial Nerve V (Trigeminal): Controls chewing muscles (motor) and provides sensation to the face (sensory).

- Cranial Nerve VII (Facial): Controls muscles of facial expression (motor) and carries taste from the front of the tongue (sensory).

- Cranial Nerve IX (Glossopharyngeal): Helps with swallowing (motor) and carries taste and sensation from the back of the tongue (sensory).

- Cranial Nerve X (Vagus): The “wandering nerve” that controls muscles in the pharynx and larynx (motor) and receives sensory information from many internal organs (sensory).

My Favorite Mnemonic for Remembering Nerve Types

Trying to keep all this straight—motor, sensory, or both (mixed)—was a nightmare for me at first. Then I discovered the classic mnemonic that every medical student learns. It’s a lifesaver. To remember the function of each of the 12 nerves in order, just remember this phrase:

“Some Say Marry Money But My Brother Says Big Brains Matter Most”

The first letter of each word tells you the nerve’s type:

- Some (CN I: Sensory)

- Say (CN II: Sensory)

- Marry (CN III: Motor)

- Money (CN IV: Motor)

- But (CN V: Both)

- My (CN VI: Motor)

- Brother (CN VII: Both)

- Says (CN VIII: Sensory)

- Big (CN IX: Both)

- Brains (CN X: Both)

- Matter (CN XI: Motor)

- Most (CN XII: Motor)

This simple phrase was a game-changer for me. It instantly organizes all 12 nerves into their correct functional categories.

Clinical Significance and Assessment

Knowing the pure motor nerves isn’t just an academic exercise. It’s a foundational piece of knowledge for any neurological examination.

Why This Classification is a Clinician’s Best Friend

When a patient comes in with a neurological complaint, a clinician has to act like a detective. The symptoms are clues, and the goal is to localize the lesion—to find exactly where the problem is in the nervous system.

The classification of cranial nerves makes this process incredibly efficient.

- If a patient has purely motor symptoms, like a drooping eyelid or a weak shoulder, the clinician can focus their investigation on the motor pathways and the five pure motor nerves.

- If the symptoms are purely sensory, like a loss of smell or hearing, they’ll look at the sensory nerves.

- If there’s a mix of motor and sensory deficits, like facial paralysis and loss of taste, a mixed nerve is the likely culprit.

This allows for a targeted assessment, saving time and leading to a more accurate diagnosis. Any complex system, from the human body to an engine, will eventually have a motor problem, and knowing how to isolate the issue is key. Just as an engineer tests individual components, a doctor tests individual cranial nerves.

Common Conditions Affecting Pure Motor Nerves

Let’s revisit our five motor nerves and see what happens when they run into trouble.

- Oculomotor, Trochlear, and Abducens Nerve Palsies: Because these three nerves work together to control the eyes, problems with them are common. They can be damaged by microvascular issues (like in diabetes), trauma, tumors, or aneurysms. The result is almost always diplopia (double vision) and strabismus (misaligned eyes), but the specific pattern of misalignment tells the doctor exactly which nerve is affected.

- Spinal Accessory Nerve Injury: As I mentioned, this nerve is often damaged accidentally during neck surgery. The result is weakness of the trapezius muscle, leading to a drooping shoulder, pain, and difficulty lifting the arm above the horizontal plane. It highlights the importance of precise anatomical knowledge during procedures.

- Hypoglossal Nerve Lesions: Strokes and motor neuron diseases like ALS can affect this nerve. The result is dysarthria (difficulty speaking clearly) and dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), along with the classic tongue deviation toward the side of the injury.

Frequently Asked Questions about Cranial Nerves

I get asked these questions all the time, so I wanted to address them directly.

Q: Are there any other pure motor cranial nerves?

A: Nope, just these five: III, IV, VI, XI, and XII. The other seven are either purely sensory (I, II, VIII) or mixed (V, VII, IX, X). This classification is a cornerstone of neuroanatomy.

Q: What’s a good mnemonic just for the pure motor nerves?

A: While the “Some Say Marry Money…” mnemonic is great for all 12, if you just want to remember the motor ones, it’s a bit trickier. I’ve heard students try to make a phrase out of the numbers: 3, 4, 6, 11, 12. Maybe something like, “At 3:46, I ate 11 or 12 M&Ms” (for ‘Motor’). It’s a bit clunky, but sometimes a personal, silly mnemonic is the one that sticks best!

Q: How are pure motor nerves tested in a clinical setting?

A: The tests are surprisingly straightforward and elegant. A clinician will ask the patient to perform actions that isolate the function of each nerve.

- CN III, IV, VI: “Follow my finger with your eyes without moving your head.” The clinician moves their finger in an “H” pattern to test all ranges of eye motion.

- CN XI: “Shrug your shoulders against my hands” (tests trapezius). “Turn your head against my hand” (tests sternocleidomastoid).

- CN XII: “Stick your tongue straight out.” The clinician looks for any deviation, atrophy, or fasciculations.

Q: What really distinguishes CN III, IV, and VI?

A: Think of it as a team with specialized roles, much like the relationship between a stator and rotor in a motor. All three move the eye, but they have different jobs.

- CN III (Oculomotor) is the general manager. It handles most movements (up, down, in) and the eyelid/pupil.

- CN VI (Abducens) is the specialist for moving the eye out.

- CN IV (Trochlear) is the specialist for moving the eye down and in.

Each is a separate nerve taking a different path from the brainstem to the eye socket, so an injury can affect one without touching the others.

My Final Thoughts: The Elegance of Motor Control

Learning the cranial nerves can feel like a brute-force memorization task. But what I’ve come to appreciate over the years is the sheer elegance of the system. The brain doesn’t use one giant, all-purpose nerve to control the head and neck. Instead, it has these 12 specialized pathways, each honed for a specific set of tasks.

The five pure motor nerves are the perfect example of this efficiency. They are the direct lines of action, the executors of the brain’s will to move. From the subtle glance of an eye to the powerful shrug of a shoulder, these nerves translate thought into motion. Understanding them isn’t just about passing an exam; it’s about appreciating the incredible, intricate wiring that makes us who we are.