Unveiling the World of Eddy Current Applications: Where This Electromagnetic Phenomenon Shapes Industries

Every engineer, designer, and technician grapples with invisible forces that dictate the success of a project. From thermal dynamics to electromagnetic fields, understanding these principles is key to innovation. If you’ve ever wondered how a roller coaster stops so smoothly, how metal is sorted at a recycling plant, or how a tiny crack in an airplane wing is found before it becomes a disaster, you’ve stumbled upon the work of one of engineering’s most versatile, yet unsung, heroes: the eddy current.

It’s a silent, invisible phenomenon. Yet, these swirling currents of electricity are a cornerstone of modern technology, quietly ensuring safety, powering industries, and even cooking your food. They represent a fundamental principle of electromagnetism put to work in dozens of practical, ingenious ways.

This guide is for the curious engineer, the diligent technician, and the forward-thinking manager. We’ll demystify eddy currents, moving beyond pure theory to explore exactly where and why they are used across countless industries. You’re in the right place to see how this fundamental force is harnessed to solve real-world challenges.

What We’ll Cover

- Introduction to Eddy Currents: A quick primer on this versatile phenomenon.

- Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) and Inspection: How eddy currents find flaws we can’t see.

- Industrial Heating and Processing: Using eddy currents to generate precise, controlled heat.

- Braking and Damping Systems: The science of stopping without touching.

- Metal Separation and Sorting: How eddy currents clean up our waste streams.

- Niche and Emerging Applications: Exploring the frontiers of eddy current technology.

- How Eddy Currents Work: The underlying physics made simple.

- Why Choose Eddy Currents? A balanced look at advantages and limitations.

- The Future of Eddy Current Technology: What’s next for this powerful tool.

Introduction to Eddy Currents: A Versatile Phenomenon

So, what exactly are these currents?

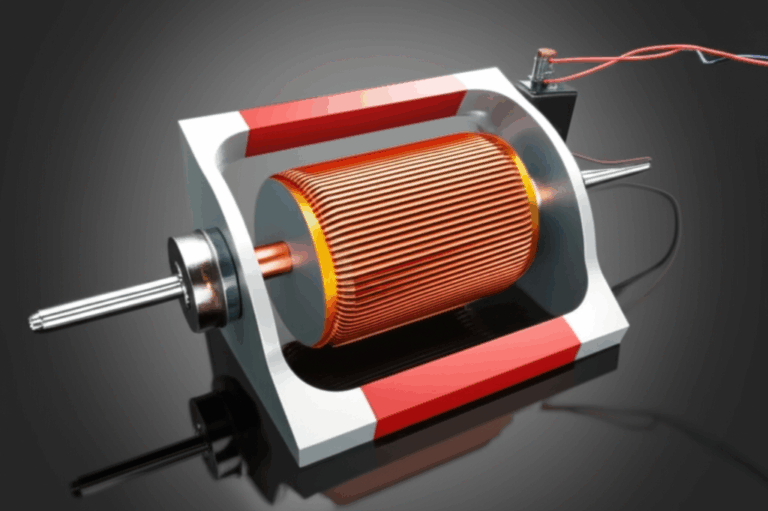

At its core, an eddy current is a localized loop of electrical current induced within a conductor by a changing magnetic field. This happens because of a fundamental law of physics called Faraday’s Law of Induction. When you move a magnet near a piece of metal or expose that metal to an alternating magnetic field, you generate electricity inside the metal itself.

Think of eddy currents like small, unwanted whirlpools in a smoothly flowing river. The river is the main electrical or magnetic path you want. The changing magnetic field is like a disturbance—a rock dropped into the water—that creates these swirling whirlpools. In some applications, like in a transformer lamination core, these “whirlpools” represent energy loss and are something to be minimized. But in many other cases, engineers have figured out how to harness these whirlpools and put them to incredibly productive use.

These induced currents create their own magnetic fields that, according to Lenz’s Law, oppose the original change that created them. It’s this interaction—this “push-back”—that we exploit. The strength and behavior of eddy currents depend on several factors: the strength of the magnetic field, the frequency of the alternating current, the electrical conductivity of the material, and its magnetic permeability. By manipulating these factors, we can make eddy currents perform a vast range of tasks.

Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) and Inspection

Perhaps the most critical application of eddy currents is in non-destructive testing (NDT), a field dedicated to inspecting materials and components without damaging them. Eddy current testing (ECT) is a fast, reliable, and powerful tool for ensuring the safety and integrity of everything from power plants to airplanes.

Detecting Cracks, Flaws, and Defects

The primary use of ECT is finding surface and near-surface defects in conductive materials. When an eddy current probe, which contains a coil generating an alternating magnetic field, is passed over a flawless metal surface, the eddy currents flow in a uniform, predictable pattern.

However, if these currents encounter a discontinuity—like a fatigue crack, a lap, or a seam—their flow is disrupted. This disruption changes the impedance of the coil in the probe, which is instantly detected by the instrument. It’s like a sonar system for metal; the instrument sends out a signal and reads the “echo” to map the terrain of the material’s surface.

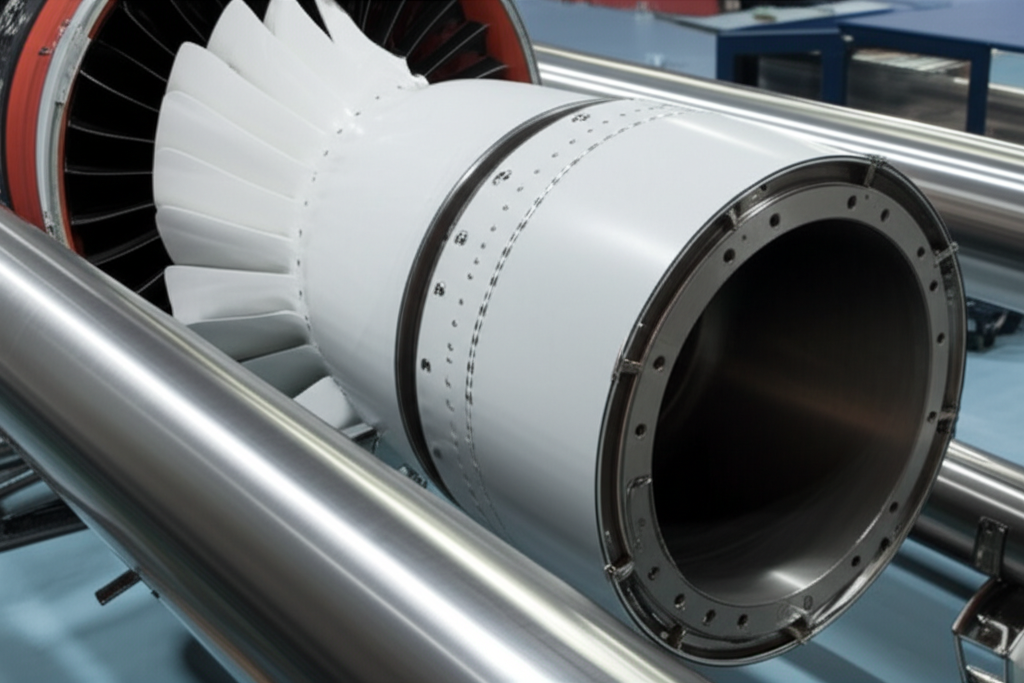

- Aerospace Inspection: This is a life-or-death application. ECT is mandated for inspecting 100% of safety-critical components like turbine blades, landing gear, and aircraft fuselages. It can reliably detect fatigue cracks as small as 0.5 mm, long before they become visible to the naked eye. It can also find sub-surface corrosion hiding under layers of paint, preventing catastrophic failures and extending the service life of an aircraft.

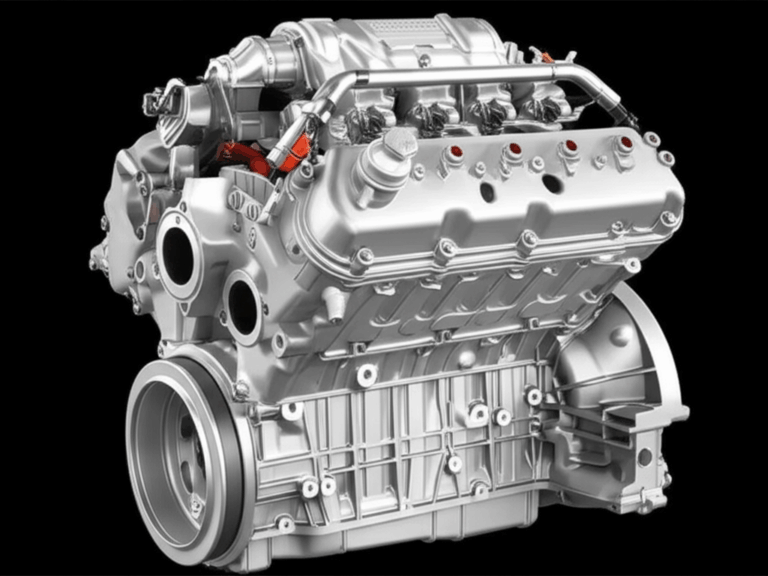

- Automotive Industry: From engine parts and chassis components to wheel rims, eddy currents are used for quality control on the production line, ensuring that every part meets stringent safety standards.

- Power Generation: In power plants, the integrity of heat exchanger tubes is paramount. ECT is used to inspect thousands of tubes for cracking, pitting, and wall thinning, preventing leaks and costly unplanned shutdowns.

Material Characterization and Property Measurement

Beyond just finding flaws, eddy currents can “read” a material’s properties. Because the way eddy currents behave is directly tied to a material’s physical characteristics, we can use them to measure:

- Electrical Conductivity: This is useful for sorting alloys, verifying the proper heat treatment of a component, or assessing heat damage. Different metal alloys have unique conductivity signatures.

- Material Thickness: ECT can precisely measure the thickness of coatings (like paint or anodizing) on a metal substrate or measure the thickness of thin metal sheets and foils.

- Hardness and Microstructure: Variations in material hardness, which often correlate with heat treatment, can also be detected, providing another layer of quality assurance in manufacturing.

Specialized NDT Techniques

The world of ECT is constantly evolving with advanced methods designed to tackle specific challenges:

- Eddy Current Array (ECA): Instead of a single coil, ECA probes use multiple coils arranged in a single assembly. This allows them to scan a much wider area in a single pass, drastically reducing inspection time by up to 50% compared to traditional methods. They also produce detailed C-scan images, which are intuitive, color-coded maps of the inspected surface, making it easier to visualize defects. This is a game-changer for inspecting large surfaces like welds on pipelines or pressure vessels.

- Pulsed Eddy Current (PEC): Standard ECT struggles to penetrate deep into a material or inspect through thick coatings. PEC overcomes this by sending a pulse of electromagnetic energy into the component and analyzing the decaying eddy current signal over time. This technique can inspect for corrosion and wall thinning through thick insulation, fireproofing, and protective coatings without the need for costly and time-consuming removal. It’s invaluable in the oil and gas industry for inspecting pipes and tanks.

- Remote Field Eddy Current (RFEC): Inspecting ferromagnetic tubes (like carbon steel) is tricky for standard ECT. RFEC is a low-frequency technique designed specifically for this. It uses a “through-transmission” method where the signal travels from an exciter coil, through the tube wall, along the outside, and back through the wall to a detector coil. This allows it to detect defects on both the inside and outside of the tube with equal sensitivity.

Industrial Heating and Processing

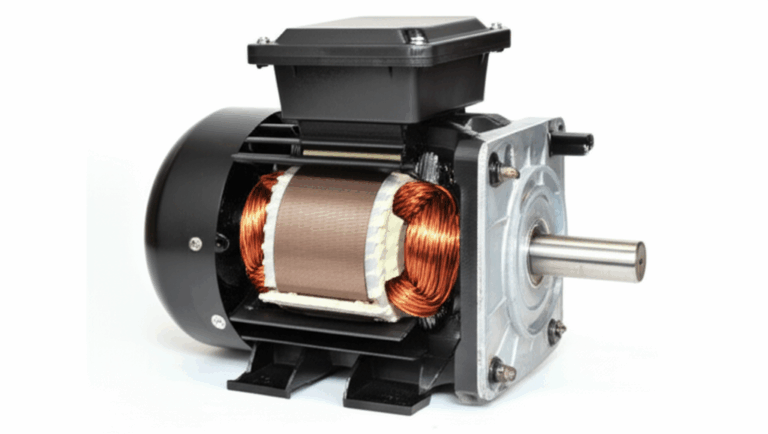

The same energy loss that engineers try to prevent in electric motors can be amplified and used for incredibly efficient heating. When eddy currents swirl through a conductor, their movement against the material’s electrical resistance generates immense heat—a principle known as Joule heating. This is the foundation of induction heating.

Induction Heating

Induction heating is a fast, precise, and clean method for heating conductive materials without any physical contact. An induction coil generates a powerful, high-frequency magnetic field. When a metal part is placed within this field, eddy currents are induced within it, causing it to heat up rapidly from the inside out.

The applications are widespread in metallurgy and manufacturing:

- Hardening and Heat Treatment: For automotive gears, shafts, and bearings, a hard, wear-resistant surface is needed while keeping the core tough and ductile. Induction hardening achieves this perfectly by heating only the surface layer in seconds, followed by a quench. This process is far more energy-efficient—often exceeding 80% efficiency compared to 20-40% for gas furnaces—and allows for precise control over the hardened depth. This is vital for the performance of complex components like the bldc stator core.

- Melting, Forging, and Brazing: In foundries, induction furnaces can melt tons of metal cleanly and efficiently. In forging operations, induction heating brings billets up to temperature in minutes, not hours, improving production rates. It’s also used for brazing and soldering, creating strong, clean joints in everything from plumbing fixtures to aerospace components.

Cooking Appliances

The most common household example of induction heating is the induction cooktop. Beneath the glass-ceramic surface is a coil of copper wire. When you turn it on, an alternating current flows through the coil, creating a magnetic field. If you place a pot made of a magnetic material (like cast iron or stainless steel) on top, the cooktop induces eddy currents directly into the base of the pot. The pot itself becomes the heater, while the cooktop surface remains cool to the touch. This makes induction cooking incredibly fast, safe, and energy-efficient.

Braking and Damping Systems

The opposing force created by eddy currents is the key to another revolutionary application: frictionless braking.

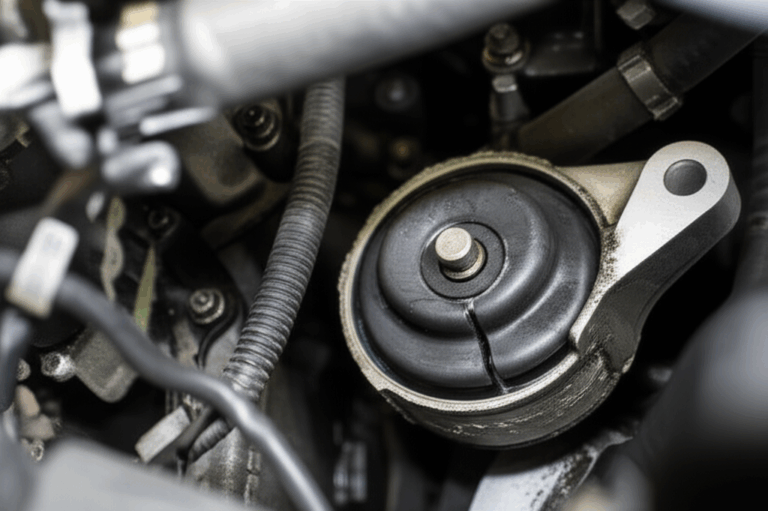

Eddy Current Brakes (Electromagnetic Brakes)

An eddy current brake consists of a non-ferrous conductive disc (like copper or aluminum) rotating between the poles of an electromagnet. When the brake is off, the disc spins freely. But when current is applied to the electromagnet, it creates a strong magnetic field through the disc.

As the disc rotates through this field, eddy currents are induced within it. These currents generate their own magnetic fields that oppose the rotation, creating a powerful braking torque that slows the disc down. The kinetic energy of the rotating object is converted directly into heat within the disc, without any parts ever touching.

This wear-free operation makes them ideal for applications requiring smooth, reliable, and low-maintenance braking:

- Roller Coasters and Amusement Rides: The silent, smooth stop at the end of a high-speed roller coaster is often the work of eddy current brakes. A series of permanent magnets on the track interact with conductive fins on the train car, bringing a 100-mph coaster to a safe stop without the screeching and wear of friction brakes. They are incredibly reliable and function independently of weather conditions.

- High-Speed Trains: In high-speed rail systems, eddy current brakes act as a supplemental system for emergency stops or for reducing speed without wearing out the primary friction brakes. In Maglev trains, which levitate above the track, they are an essential part of the non-contact braking system.

- Heavy Vehicles and Dynamometers: Some heavy trucks use eddy current retarders to assist with braking on long downhill grades, saving the service brakes from overheating. They are also used in dynamometers for testing the torque and power output of engines and motors.

Vibration Damping

The same principle can be used on a smaller scale to damp unwanted vibrations in sensitive equipment. By strategically placing magnets and conductors, the relative motion (vibration) induces eddy currents that create a drag force, effectively smoothing out the motion and stabilizing the system.

Metal Separation and Sorting

In the massive and growing recycling industry, separating valuable metals from a stream of mixed waste is a critical challenge. Eddy current separators (ECS) are the elegant solution for recovering non-ferrous metals.

Eddy Current Separators (ECS)

An ECS works by passing mixed waste on a conveyor belt over a rapidly rotating drum embedded with powerful permanent magnets. This spinning magnetic field induces intense eddy currents in any conductive metals in the waste stream, such as aluminum cans, copper wire, and brass fittings.

As we know, these eddy currents create their own opposing magnetic field. This results in a strong repulsive force that literally throws the non-ferrous metals forward, off the conveyor belt and into a separate collection bin. Other materials like plastic, glass, wood, and paper are unaffected and simply fall off the end of the conveyor.

This technology is essential for the circular economy. ECS units can recover non-ferrous metals from municipal solid waste, shredded cars, and electronic waste with a purity often exceeding 95-98%. This diverts millions of tons of valuable material from landfills and significantly reduces the energy needed to produce metals from virgin ore. It’s a key reason why recycling aluminum is so economically viable. The careful construction of these machines often involves high-quality electrical steel laminations to manage the powerful magnetic fields involved.

Metal Detection

On a simpler scale, the common metal detector operates on the same principle. A handheld detector or an airport security gate generates a primary magnetic field. When a conductive object (like a coin, keys, or a weapon) passes through this field, it disrupts the field by inducing eddy currents within the object. The detector’s receiver coil senses this change and triggers an alarm. This technology is crucial for security screening, where it is used on over 4.5 billion airline passengers annually, as well as in industrial quality control to detect stray metal fragments in food, pharmaceuticals, and textiles.

Niche and Emerging Applications

The versatility of eddy currents continues to inspire innovation in more specialized fields.

- Levitation (e.g., Maglev Trains): In some Maglev designs, eddy currents are used for repulsion. As the train’s powerful magnets move at high speed over conductive coils or plates in the guideway, they induce strong eddy currents. The resulting repulsive magnetic force is powerful enough to lift the entire train, allowing for frictionless, high-speed travel.

- Medical and Biomedical: While MRI is a different magnetic phenomenon, eddy currents play a role in the design of its gradient coils. Researchers are also exploring miniaturized eddy current sensors for medical devices and for specific diagnostic tools that can measure changes in biological tissue conductivity.

- Currency Validation and Security: Vending machines and other automated payment systems use eddy current sensors to validate coins. Each type of coin has a specific metallic composition, giving it a unique conductive signature that the machine can recognize to determine its value and authenticity.

How Eddy Currents Work: The Underlying Principles (Briefly)

To truly grasp the applications, it helps to understand the “why.” The behavior of eddy currents is governed by a few key factors:

Why Choose Eddy Currents? Advantages and Limitations

Like any technology, eddy currents have a distinct set of pros and cons that make them the perfect choice for some jobs and unsuitable for others.

Advantages:

- Non-Contact: For braking, heating, and testing, no physical contact is required, which eliminates wear and tear.

- High Speed and Sensitivity: ECT is extremely fast and can detect incredibly small surface defects.

- Precision and Control: Induction heating allows for precise control over the heated area and temperature.

- Automation Potential: The speed and reliability of eddy current systems make them easy to integrate into automated production and inspection lines.

- Environmentally Friendly: NDT requires no chemicals or consumables, and induction heating is highly energy-efficient.

Limitations:

- Conductive Materials Only: Eddy currents can only be induced in materials that conduct electricity. They cannot be used to inspect plastics, ceramics, or composites.

- Limited Depth of Penetration: Standard ECT is primarily a surface and near-surface inspection method due to the skin effect.

- Sensitivity to Geometry: Complex shapes and rough surfaces can make inspection challenging and may require specialized probes.

- Requires Skilled Operators: Interpreting eddy current signals in NDT requires extensive training and certification to differentiate between defect signals and noise from irrelevant variables.

The Future of Eddy Current Technology

The field is far from static. The future promises even more sophisticated applications driven by advancements in sensor technology, data processing, and artificial intelligence.

- Integration with AI: Machine learning algorithms are being developed to analyze complex eddy current signals automatically, reducing the burden on human inspectors and improving the accuracy and consistency of flaw detection.

- Miniaturization and Wireless Probes: Smaller, more powerful sensors and wireless technology will enable inspections in hard-to-reach areas without cumbersome cables.

- Advanced Array Technology: The trend towards larger and more flexible eddy current arrays will continue, allowing for faster inspection of complex geometries, such as the curved surfaces of an aircraft fuselage.

- Structural Health Monitoring: The dream is to embed or permanently install eddy current sensors into critical structures like bridges, pipelines, and aircraft to provide continuous, real-time monitoring of their structural health.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Role of Eddy Currents

From the silent, steady braking of a train to the invisible scan that guarantees the integrity of a critical weld, eddy currents are a powerful and pervasive force in our technological world. They are a testament to engineering ingenuity—taking a fundamental principle of physics and transforming it into a vast array of practical tools that enhance safety, improve efficiency, and enable new possibilities.

For the engineer and designer, understanding the capabilities of eddy currents opens a toolbox for solving challenges in quality control, manufacturing, and mechanical systems. Whether you are detecting flaws, heating materials, sorting recyclables, or bringing a machine to a gentle halt, this remarkable electromagnetic phenomenon is very often the smartest, cleanest, and most elegant solution.

Your Engineering Takeaway

- Eddy currents are versatile: They are used for inspection (NDT), heating, braking, and sorting across dozens of industries.

- The application dictates the approach: High frequencies are used for surface inspection, while lower frequencies offer deeper penetration for heating or flaw detection.

- It’s a non-contact force: This key advantage eliminates mechanical wear in braking systems and allows for clean, precise heating.

- Material properties are key: The technology is limited to conductive materials, and its effectiveness depends on the material’s specific conductivity and permeability.

- The technology is advancing: Innovations in array probes, pulsed systems, and AI-driven analysis are continuously expanding the power and reach of eddy current applications.

Armed with this understanding, you are better equipped to identify opportunities where this invisible force can be put to work, leading to safer products, more efficient processes, and smarter designs.