What Are Eddy Current Losses? Understanding the Basics, Causes, and Mitigation

Every engineer, designer, and manager involved in creating electrical machines faces a common challenge: the relentless pursuit of efficiency. You’re constantly weighing the trade-offs between performance, thermal management, and production cost. In this battle against wasted energy, one of the most significant yet often misunderstood adversaries is eddy current loss. If you’ve ever found yourself trying to optimize a motor, transformer, or inductor design and wrestling with unexplained heat or lower-than-expected efficiency, you’re in exactly the right place.

This is a deep dive into eddy current losses, but we’re going to skip the dense textbook jargon. Instead, think of this as a conversation with an engineering partner. We’ll break down the fundamental physics, explore what causes these losses, and most importantly, discuss the practical, real-world strategies you can use to mitigate them. By the end, you’ll not only understand what eddy current losses are but also feel empowered to make more informed design and material choices for your next project.

What We’ll Cover

- The Physics Behind Eddy Current Losses: How do these energy-wasting currents actually form?

- Key Factors Influencing Eddy Current Losses: What design and material choices make them better or worse?

- Why Eddy Current Losses Matter: Understanding their impact on efficiency, heat, and cost.

- Strategies to Reduce Eddy Current Losses: Your practical guide to taming this invisible force.

- Where Are Eddy Currents Found?: A look at both their harmful effects and surprising benefits.

- Simplified Formula for Eddy Current Losses: A practical tool for design intuition.

- Eddy Current Losses vs. Hysteresis Losses: Clarifying the two main types of core loss.

The Physics Behind Eddy Current Losses: How They Occur

At its heart, the phenomenon of eddy currents is a direct consequence of one of the foundational principles of electromagnetism, discovered by the brilliant scientist Michael Faraday. You don’t need a Ph.D. in physics to grasp it; a simple analogy will do the trick.

Electromagnetic Induction (Faraday’s & Lenz’s Laws)

Faraday’s Law of Induction states that if you change a magnetic field near a conductive material, you will induce a voltage, or what’s technically called an electromotive force (EMF), within that material. Think of it like this: a moving magnetic field “pushes” the electrons in the conductor, creating electrical pressure. The faster the magnetic field changes, the stronger the push.

Lenz’s Law adds a crucial detail: the direction of this induced current will always be such that it creates its own magnetic field that opposes the original change. Nature, it seems, resists change. This push-and-pull is the engine behind eddy current formation.

Formation of Eddy Currents

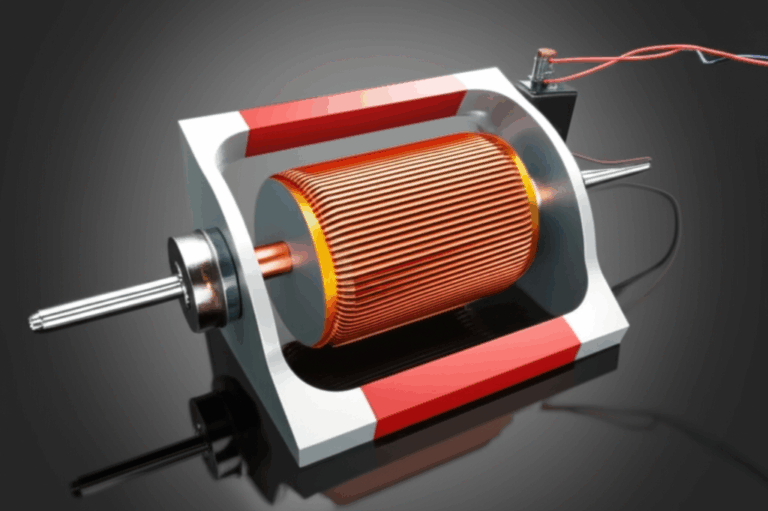

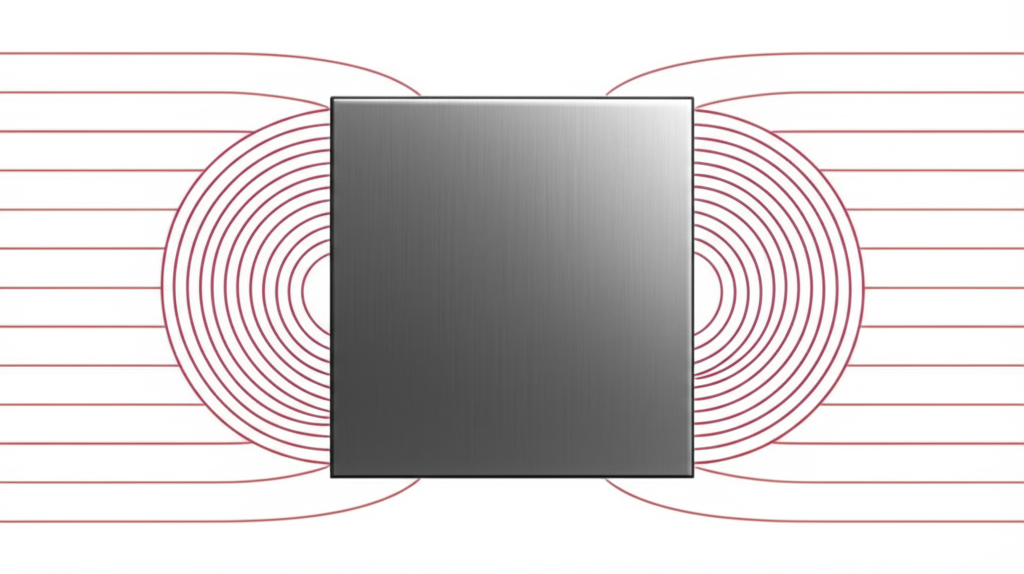

Now, imagine a solid block of iron or copper inside a coil of wire carrying an alternating current (AC). The AC current creates a magnetic field that is constantly and rapidly changing direction and strength. According to Faraday’s Law, this changing magnetic flux induces voltages all throughout the iron block.

Since the iron is a conductor, these voltages cause currents to flow. But these currents don’t have a neat wire to follow. Instead, they form small, circulating loops within the material itself.

Here’s the key analogy: Think of eddy currents like small, unwanted whirlpools in a river. The main flow of the river is the energy you want to use, but the changing magnetic field creates these chaotic, swirling eddies of electrical current within the core material. These currents, also known as Foucault currents, do no useful work. They just spin around, consuming energy.

The Joule Heating Effect

So, what happens to the energy consumed by these swirling currents? It turns into heat. This is due to a principle called Joule heating, described by the simple formula P = I²R. It means that any current (I) flowing through a material with electrical resistance (R) will dissipate power (P) as heat.

Since the conductive core material has inherent resistance, these circulating eddy currents generate heat. A lot of it. This heat is the “eddy current loss.” It’s energy that should have been converted into useful magnetic flux or mechanical work but is instead wasted as thermal energy, warming up the component and reducing the overall system efficiency.

Key Factors Influencing Eddy Current Losses

Understanding that eddy currents are wasteful whirlpools is the first step. The next, more critical step for any engineer is knowing which knobs to turn to make those whirlpools smaller and less impactful. The losses are not random; they are governed by a few key parameters.

Frequency of the Magnetic Field (f)

This is one of the biggest factors. Eddy current losses are proportional to the square of the frequency (f²). This means if you double the operating frequency of your device, you don’t just double the losses—you quadruple them.

For instance, moving a design from a standard 60 Hz grid application to a 400 Hz aerospace application theoretically increases eddy current losses by a factor of (400/60)², which is roughly 44 times! This quadratic relationship is why managing these parasitic losses is absolutely paramount in high-frequency power electronics, switched-mode power supplies, and variable frequency drives.

Material Properties

The material you choose for your magnetic core is a critical decision. Two properties are especially important:

- Electrical Resistivity (or its inverse, Conductivity σ): Higher resistivity makes it harder for currents to flow. Think of it as adding rocks and obstacles to the riverbed, which disrupts the formation of strong whirlpools. Materials with high electrical resistivity will have lower eddy current losses. This is why pure iron, a great conductor, is a poor choice for AC applications. Instead, engineers use materials like silicon steel, where adding silicon significantly increases resistivity.

- Magnetic Permeability (μ): Permeability is how easily a material allows magnetic field lines to pass through it, much like how a sponge easily soaks up water. While high permeability is generally good for creating a strong magnetic circuit, very high permeability can sometimes concentrate the flux and contribute to higher losses if not managed properly.

Material Geometry (Thickness, t)

Here’s where the physical design of the core comes into play. Eddy current losses are also proportional to the square of the material’s thickness (t²) perpendicular to the magnetic flux.

A thick, solid block of metal provides a wide, easy, low-resistance path for large eddy currents to form. It’s like a deep, wide river allowing for massive whirlpools. But what if you could break that river up into many tiny, shallow streams? That’s precisely the idea behind laminations. By using a stack of very thin sheets, you dramatically shrink the path available for the currents, forcing them into much smaller, higher-resistance loops and slashing the resulting losses. A case study shows that reducing lamination thickness by just 50% (e.g., from 0.5 mm to 0.25 mm) can decrease eddy current losses by up to 75%.

Magnetic Flux Density (B)

Finally, the strength of the magnetic field itself plays a role. Losses are proportional to the square of the maximum magnetic flux density (B²). A stronger magnetic field induces a larger voltage, which drives larger eddy currents, leading to greater heat dissipation. This means pushing a core material closer to its magnetic saturation point will not only risk poor magnetic performance but will also dramatically increase core losses.

Why Eddy Current Losses Matter: Consequences and Impact

Okay, so there are some energy losses. But what’s the real-world bottom line? Why should you dedicate design time and budget to mitigating them? The consequences are significant and ripple through the entire lifecycle of a product.

Reduced Efficiency in Electrical Devices

This is the most obvious consequence. In devices like transformers, motors, and generators, eddy current losses represent a direct drain on efficiency. A portion of the electrical energy you put in is immediately converted to useless heat instead of performing its intended function. Globally, it’s estimated that core losses in electrical machines contribute to 0.5% to 1.5% of all generated electrical power being wasted. That amounts to hundreds of billions of kilowatt-hours annually—a staggering economic and environmental cost.

Excessive Heat Generation

Wasted energy doesn’t just disappear; it becomes heat. Excessive heat is the enemy of reliability. High operating temperatures can:

- Degrade Insulation: The insulation on copper windings is often the first thing to fail, leading to short circuits and catastrophic device failure.

- Cause Thermal Runaway: In some cases, as the component gets hotter, its properties can change in a way that increases losses further, creating a vicious cycle of ever-increasing temperature.

- Require Bulky Cooling Systems: The need to dissipate this extra heat often requires larger heat sinks, fans, or even liquid cooling systems, adding cost, size, and complexity to the final design. In high-power converters, these losses can create localized “hot spots” exceeding 150°C, a critical challenge for thermal management.

Wasted Energy and Economic Costs

For any application, from a massive grid transformer to a tiny power converter, wasted energy is wasted money. Upgrading older industrial motors with cores made from more advanced materials can improve efficiency by 1-2%. While that sounds small, for a large industrial facility, a 1% gain can translate into tens of thousands of dollars in annual electricity savings.

Performance Degradation

The combination of lower efficiency and higher temperatures leads to overall performance degradation. A motor won’t deliver its rated torque, a transformer’s voltage regulation may suffer, and the lifespan of the entire system will be shortened. Managing eddy current losses isn’t just about saving a few watts; it’s about ensuring the device performs reliably for its entire service life.

Strategies to Reduce Eddy Current Losses

Fortunately, engineers have developed several highly effective strategies to combat eddy current losses. The right approach depends on the application, frequency, and cost targets.

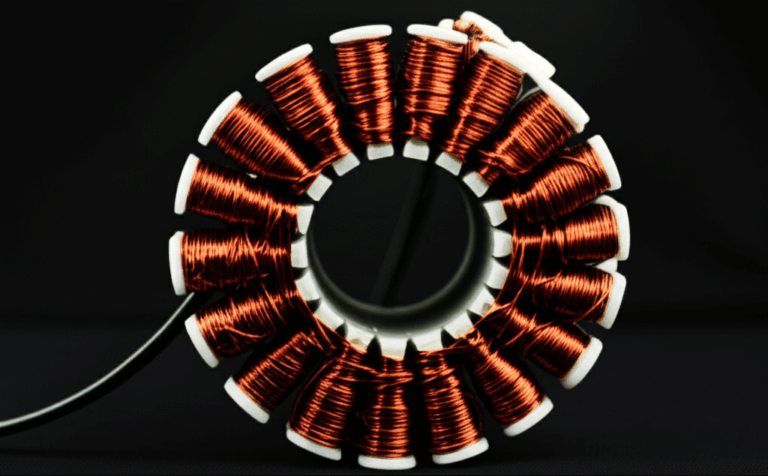

Laminated Cores

This is the single most common and effective technique. Instead of using a solid core, the core is constructed from a stack of very thin sheets, or laminations. Each sheet is coated with a thin, insulating layer (like varnish or an oxide layer).

This design brilliantly breaks up the large, low-resistance paths that eddy currents love. The currents can still form within each individual lamination, but because the laminations are so thin, the loops are tiny and their path resistance is very high. This fundamentally constrains the “whirlpools,” drastically reducing the overall loss. The quality of the electrical steel laminations is therefore a primary factor in the efficiency of the final device.

Using High-Resistivity Materials

Choosing the right material is your next line of defense. The goal is to select a material with high electrical resistivity without compromising too much on desirable magnetic properties like high permeability and low hysteresis.

- Silicon Steel: This is the workhorse of the industry for motors, generators, and transformers operating at grid frequencies (50/60 Hz). Adding a small percentage of silicon (typically up to 3-4%) to iron increases its resistivity by four to five times, slashing eddy current losses by 80% or more compared to pure iron. There are various grades of silicon steel laminations optimized for different performance levels.

- Amorphous Metals: For higher-frequency applications, amorphous metals offer even higher resistivity and come in the form of extremely thin ribbons (around 0.025 mm). They can have 60-70% lower overall core losses than the best silicon steels.

- Ferrites: At very high frequencies (kilohertz to megahertz), metallic cores become untenable. Ferrites, which are ceramic magnetic materials, are the solution. They are essentially electrical insulators, so their resistivity is enormous. This makes eddy current losses practically negligible, though they have other limitations like lower magnetic saturation levels.

- Cobalt Alloys: In high-power-density and high-performance applications like aerospace, cobalt-iron alloys offer superior magnetic saturation and performance at high temperatures, but at a significant cost premium.

Optimized Core Geometry and Design

The shape of the core matters. Designing a magnetic circuit to ensure the flux path is as uniform as possible and that the cross-sectional area perpendicular to the flux is minimized can help reduce losses. Toroidal (donut-shaped) cores, for example, are excellent at containing the magnetic flux within the core, reducing leakage flux that can cause eddy currents in nearby conductive components.

Where Are Eddy Currents Found? (Both Harmful & Beneficial)

While engineers spend a lot of time fighting eddy currents, it’s important to remember that they are a natural phenomenon—and sometimes, a very useful one.

Harmful Examples (Where Losses Are Undesirable)

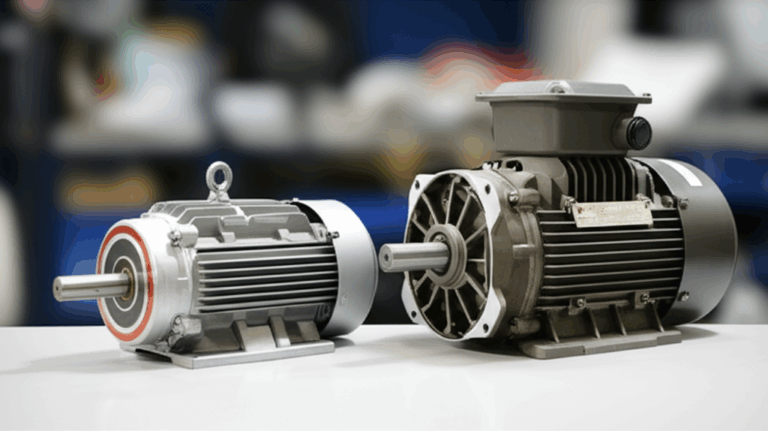

This is where most of our focus has been. The generation of eddy currents in the magnetic cores of these devices is a primary source of energy waste and heat.

- Transformers: Losses in the transformer lamination core directly reduce the efficiency of power transfer.

- Motors and Generators: Core losses in both the stator and rotor components reduce mechanical output and generate heat that must be managed.

- Inductors and Power Electronics: In high-frequency switched-mode power supplies, eddy currents are a dominant loss mechanism that limits power density and efficiency.

Beneficial Applications (Where Eddy Currents Are Utilized)

Sometimes, we can put those “whirlpools” to good use. By intentionally inducing large eddy currents, we can leverage the resulting effects.

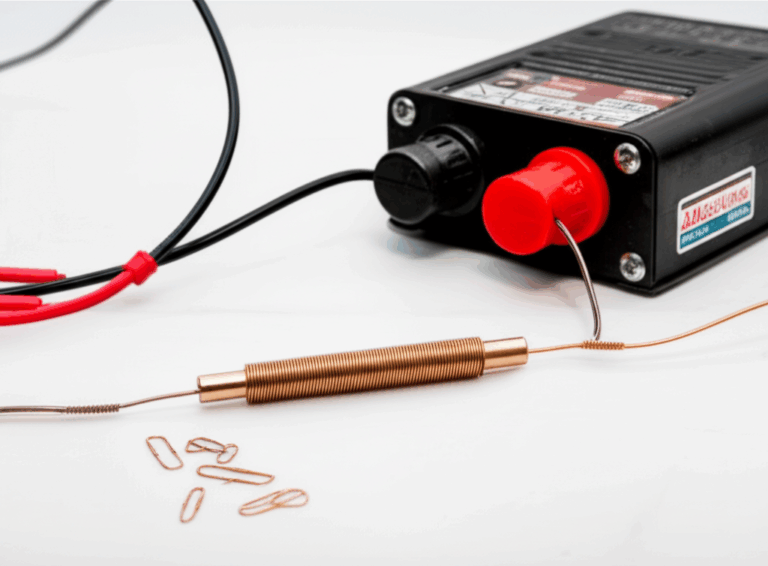

- Induction Heating: By placing a conductive workpiece (like a steel part) inside a strong, high-frequency magnetic field, we can induce massive eddy currents within it. The resulting Joule heating can raise the part’s temperature to hundreds or thousands of degrees in seconds, perfect for applications like heat treating, forging, or even induction cooktops.

- Eddy Current Braking: This technology provides smooth, frictionless braking. A strong magnet is moved past a conductive but non-magnetic disc (like aluminum or copper). This induces eddy currents in the disc, which in turn create an opposing magnetic field that slows the disc down. You’ll find these systems on high-speed trains and roller coasters.

- Metal Detectors: A metal detector works by generating a changing magnetic field in a search coil. When a conductive object passes nearby, eddy currents are induced in the object. These currents create their own weak magnetic field, which the detector’s receiver coil picks up, triggering an alert.

- Non-Destructive Testing (NDT): Eddy current probes can be used to detect cracks and flaws in conductive materials. A crack disrupts the normal flow of the induced eddy currents, and this disturbance can be measured by the probe.

Simplified Formula for Eddy Current Losses

While precise calculations require complex finite element analysis (FEA) software, a simplified formula of proportionality is incredibly useful for building engineering intuition. It encapsulates all the factors we’ve discussed:

$P_e \propto f^2 B^2 t^2 \sigma$

Where:

- $P_e$ = Eddy Current Power Loss

- $f$ = Frequency

- $B$ = Maximum Flux Density

- $t$ = Lamination Thickness

- $\sigma$ = Electrical Conductivity of the material

You don’t need to memorize the constants, but deeply understanding these squared relationships is a superpower for any designer. It tells you instantly that doubling the frequency is far more detrimental than doubling the flux density (in terms of its effect on losses) and that halving the lamination thickness is a powerful tool for loss reduction.

Eddy Current Losses vs. Hysteresis Losses (Brief Comparison)

When engineers talk about “core loss” or “iron loss,” they are typically referring to the sum of two separate phenomena: eddy current losses and hysteresis losses. It’s crucial to know the difference.

- Eddy Current Losses: As we’ve covered, these are due to induced

I²Rheating from circulating currents. They are highly dependent on frequency, thickness, and material resistivity. Think whirlpools. - Hysteresis Losses: This is the energy lost due to the friction of repeatedly realigning the microscopic magnetic domains within the material every time the magnetic field reverses. Imagine you have a box full of tiny compasses and you have to use energy to physically flip them all back and forth 60 times a second. That energy is lost as heat. This loss depends on the material’s properties (specifically the area of its B-H hysteresis loop) and is proportional to frequency (not frequency squared). Think magnetic friction.

Together, these two loss mechanisms account for the majority of energy wasted in a magnetic core. At lower frequencies, they can be comparable, but as frequency rises, eddy current losses quickly begin to dominate.

Your Engineering Takeaway

Managing eddy current losses is not an esoteric academic exercise; it’s a fundamental aspect of designing efficient, reliable, and cost-effective electrical systems. By understanding the core principles, you can move from guessing to making strategic decisions.

Here are the key takeaways to empower your next design:

- Losses are Proportional to Squares: Remember that losses skyrocket with frequency (f²), thickness (t²), and flux density (B²). This should guide your intuition when making design trade-offs.

- Lamination is Your First Defense: Never use a solid core for an AC application. Using thin, insulated laminations is the most powerful and common method for breaking up wasteful eddy currents.

- Material Selection is Critical: Choose materials with high electrical resistivity for the operating frequency of your application. This often means silicon steel for low frequencies and ferrites or amorphous metals for high frequencies.

- Heat is the Enemy: Eddy current losses manifest as heat. Always consider the thermal implications of your core design, as heat is a primary driver of component failure and reduced lifespan.

Understanding these invisible currents empowers you to control them. It allows you to have more productive conversations with material suppliers and manufacturing partners, leading to a final product that is not only more efficient and reliable but also more competitive in the market.