What Are Outboard Motors? Your Essential Guide to Marine Propulsion

Every engineer who touches a boat program wrestles with the same core question. What propulsion system gives you the performance you need without blowing your weight, budget, compliance, and maintenance targets. If you’re comparing outboard motors to inboard or sterndrive options or you’re exploring electric outboard motors for a quiet, efficient, and low‑emissions solution you’re in the right place.

At its simplest an outboard motor is a self‑contained engine unit mounted on a boat’s transom. It combines the engine, gearbox, and propeller into one compact marine propulsion system. That architecture packs a lot of advantages. You get power and easy serviceability. You also get flexible installation and strong resale value. And if you’re looking at electric outboard motors you’ll appreciate a quieter ride and simpler drivetrains.

This guide breaks down how outboard motors work, which types fit which boats, and how to weigh key specifications like horsepower, shaft length, torque, propeller pitch, and fuel consumption. You’ll also see a clear engineering explainer on motor laminations and core losses. If you specify or buy traction motors you know this part matters. Laminations directly impact efficiency, thermal performance, and durability in electric outboards and in the alternators found in gasoline outboards.

Before we dive in let’s map the route.

In This Article

- What Exactly Is an Outboard Motor?

- How Outboard Motors Work: The Core Mechanism

- Anatomy of an Outboard: Key Components Explained

- Types of Outboard Motors: Finding the Right Fit

- The Advantages of Outboard Motors

- Where You’ll See Outboards in Action

- Engineering Fundamentals: Why Motor Laminations Matter in Outboards

- Your Options Explained: Lamination Materials and Manufacturing

- Which Application Is This For? Matching Solutions to Boats and Business Goals

- Outboards in Context: Outboard vs Inboard vs Sterndrive

- A Brief History of Outboards

- Cost, Maintenance, Reliability, and Environmental Considerations

- Specifying an Outboard: A Practical Checklist

- Your Engineering Takeaway

What Exactly Is an Outboard Motor?

A concise definition helps. An outboard motor is a self‑contained external power unit that bolts to a boat’s transom. It houses the engine, a gearcase with reduction gears, and a propeller. The unit pivots to steer the boat by redirecting thrust. You can raise or lower it with power trim and tilt to optimize performance or clear shallow water.

Why do builders and operators love them. Because outboards free interior space, simplify maintenance, and scale from tiny portable 2 to 6 horsepower motors to 600+ horsepower V12 units. They power dinghies, bass boats, pontoons, small workboats, and high‑performance center consoles.

From a market view outboards dominate. In the U.S., outboards represent roughly 85% of new powerboat engine sales according to NMMA data. Global market estimates put outboard sales around $11 billion in 2023 with growth projected at about 5.5% CAGR through 2032. Electric outboard motors grow even faster with double‑digit CAGRs in several reports.

How Outboard Motors Work: The Core Mechanism

Outboards follow a simple propulsion principle. The engine converts fuel or electrical energy into mechanical power. That power passes down a driveshaft to a right‑angle gearcase that turns a propeller. The propeller accelerates water rearward and the boat moves forward. Newton still gets the last word.

- Integrated design: The powerhead (engine block, cylinders, fuel injection or carburetor, ignition system, alternator, and ECU) sits on top. The midsection carries the driveshaft, exhaust, and cooling water passages. The lower unit houses the gearcase assembly, water intake, propeller shaft, and skeg.

- Steering and control: You steer by rotating the entire motor which redirects thrust. Smaller motors use a tiller handle. Larger motors use remote control with cables or electro‑hydraulic steering.

- Trim and tilt: Power trim adjusts the thrust line to balance bow rise, planing, and fuel efficiency. Tilt lifts the motor to clear obstacles or trailer the boat.

On electric outboard motors the principle stays the same. The power source changes. A battery feeds an inverter which drives a BLDC or PMSM motor in place of a combustion powerhead. The rest of the drivetrain looks familiar with a shaft, reduction gearset, and prop. Some designs use direct drive.

Anatomy of an Outboard: Key Components Explained

Let’s unpack the “stack” from top to bottom. Knowing the pieces helps you spec, maintain, and troubleshoot.

- Powerhead assembly: The engine block and cylinders do the heavy lifting. Four‑stroke engines dominate because they run quieter, deliver better fuel efficiency, and meet emissions standards more easily. Two‑stroke direct injection designs still show up because they boast a strong power‑to‑weight ratio. You’ll find the ECU, ignition system, spark plugs, and fuel system up here. Modern motors use fuel injection rather than carburetors for cold starts and emissions control. An alternator charges onboard batteries. Displacement in cubic centimeters and cylinder count drive torque and horsepower curves.

- Midsection: Think of it as the backbone. It houses a long driveshaft that carries power to the lower unit. Hot exhaust gases flow through cast passages and exit near the prop hub. The cooling system pulls water up from the lower unit with a water pump impeller then pushes it through the jacketed engine block and thermostat before dumping it overboard.

- Lower unit: Here’s the foot. The gearcase reduces RPM and redirects torque 90 degrees to the propeller shaft. You’ll also see the water intake system, a cavitation or anti‑ventilation plate, and a skeg for protection and directional stability. The gearcase runs in oil. Routine service checks seal integrity because a little water intrusion shortens gear life fast.

- Propeller: Diameter and pitch control load and speed. A higher pitch prop increases top speed at the cost of holeshot. You size the prop to let the engine hit its rated WOT RPM range. That’s how you keep fuel consumption and reliability in the green.

- Mounting bracket and transom interface: Shaft length and transom height must match. Short, long, and extra‑long shafts suit different transom heights. Mounting holes and clamp brackets secure the motor. This interface must carry thrust, torque reactions, and impact loads.

- Control systems: Small motors favor a tiller handle with integrated throttle and shift. Larger boats move to remote control boxes and helm steering. Many boats add power trim and tilt for easier trim adjustment and shallow‑water running.

- Corrosion protection: Saltwater motors lean on anodes for corrosion protection. You’ll see replaceable zinc or aluminum anodes mounted on the lower unit and bracket. They sacrifice themselves to protect the gearcase and other metal parts. Rinse after use. Inspect anodes often.

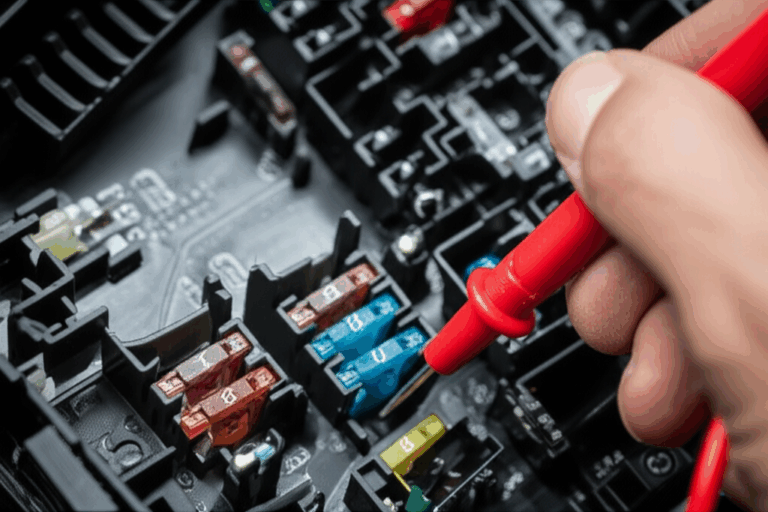

- Diagnostics and electronics: Modern outboards use an electronic control unit with integrated sensors. Dealers plug in diagnostic tools to read codes and parameters for fast troubleshooting. Some brands offer NMEA 2000 connectivity.

- Noise and vibration: Manufacturers tune intake and exhaust paths and add balance shafts or mounts to control noise and vibration. Modern four‑strokes often run 10 to 20% lower in decibel levels than older two‑strokes of the same horsepower.

Types of Outboard Motors: Finding the Right Fit

You can group outboards by cycle, power source, horsepower, and shaft length. The right choice depends on your boat, load profile, and range targets.

- Two‑stroke outboard motors: Lighter and punchier. Older carbureted versions ran dirty. Modern direct injection two‑strokes deliver better fuel efficiency and emissions control. They still shine where power‑to‑weight matters.

- Four‑stroke outboard motors: Quieter, more fuel efficient, and cleaner. These engines dominate today’s market. They pair well with fishing boats, pontoons, and family runabouts.

- Gasoline outboards: The most common power source with a wide range of horsepower ratings. From portable 2 to 6 HP units for dinghies to 150+ HP mid‑range to 600+ HP high performance units that push large center consoles at speed.

- Electric outboard motors: A growing segment. They provide quiet operation and zero local emissions. They fit lakes with strict environmental regulations and users who value low maintenance. They also power trolling motors for precise fishing control. Brands like Torqeedo and Minn Kota have pushed this technology forward.

- Diesel outboards: Less common yet available for commercial and military roles where diesel logistics and safety drive the spec.

- Horsepower categories:

- Portable under 25 HP: Tenders and small boats. Easy to remove and carry.

- Mid‑range 25 to 150 HP: Pontoon boats, fishing boats, and runabouts.

- High performance 150+ HP: Offshore center consoles and speedboats. Often rigged as twins, triples, or quads.

- Shaft length: Short, long, and extra‑long lengths must match transom height measurement. Get this wrong and you invite ventilation, poor cooling water pickup, and sluggish planing.

Note freshwater vs saltwater models. Saltwater outboards carry stronger corrosion protection, stainless hardware, and tougher coatings.

The Advantages of Outboard Motors

Outboards earned their lead for good reasons.

- Easy maintenance and service: You can tilt the motor and service it on the transom. Access beats contortionist work in a cramped engine bay. Labor hours drop for routine maintenance tasks like spark plug changes, gear oil changes, or water pump impeller service.

- Space efficiency: No engine box in the cockpit or cabin. You reclaim space for passengers, storage, or fishing gear.

- Shallow water access: Power trim and tilt let you run shallow. Kick the motor up to avoid obstacles and then drop it for deeper runs.

- Portability: Smaller outboards are truly portable. You can remove them for storage, transport, or theft deterrence.

- Power‑to‑weight: Outboards deliver strong thrust for their size. Modern engines pair refined torque curves with smart gear ratios and optimized propeller design.

- Replaceability: You can unbolt and upgrade when technology shifts. That flexibility reduces lifecycle risk.

- Noise and emissions: Newer four‑stroke gasoline outboards cut noise and emissions compared to older two‑strokes. Electric outboards lower both even further.

Where You’ll See Outboards in Action

- Recreational boating: From dinghies to family cruisers. Outboards carry a huge swath of recreational boating in the U.S. with around 85 million Americans participating each year.

- Fishing: Bass boats, center consoles, skiffs, and flats boats rely on responsive throttle and shallow water handling.

- Pontoons and deck boats: Smooth torque and quiet operation matter on social boats.

- Commercial and utility: Tenders, small workboats, and rescue vessels depend on fast serviceability and downtime minimization.

You’ll spec for cruising speed, top speed, and fuel efficiency. Pick a cruising RPM where the motor runs in its happy zone with low noise and good burn rate. That choice defines range and passenger comfort.

Engineering Fundamentals: Why Motor Laminations Matter in Outboards

If you’re designing or sourcing electric outboards or the alternators inside gasoline outboards this section pays for itself. The core question sounds like this. How do lamination thickness, material selection, and manufacturing method affect efficiency, torque ripple, heat, and noise.

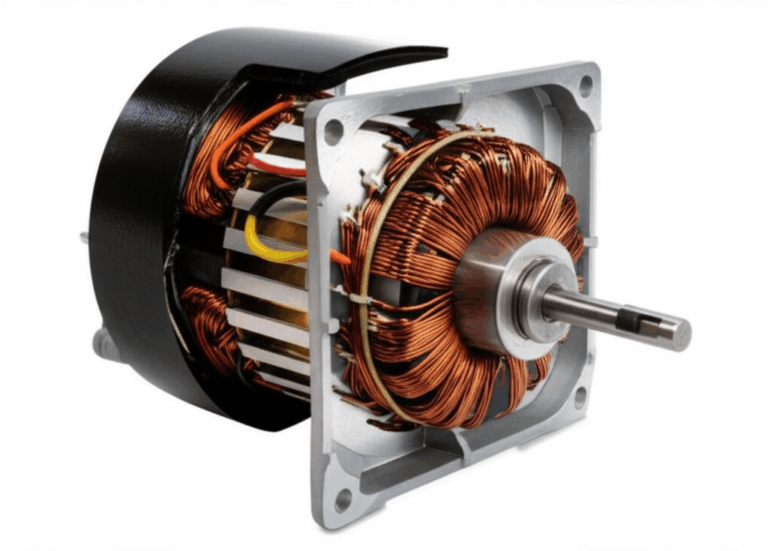

Here’s the short version. Laminations control core losses. Two primary mechanisms steal energy from your motor core: hysteresis loss and eddy current loss.

- Hysteresis loss: Magnetic domains inside the electrical steel flip direction with each AC cycle. That switching costs energy and shows up as heat. Materials with lower coercivity reduce this loss. If the B‑H curve shows steep slopes and a narrow loop you win. Think of coercivity as the material’s resistance to being demagnetized.

- Eddy current loss: Changing magnetic fields induce circulating currents in the core. Those currents create heat that does nothing useful. Laminations with thin insulated sheets break up the current paths and slash those losses.

Analogy time. Imagine a river after a storm. Large whirlpools waste energy and slow flow. Eddy currents act like those whirlpools inside a motor core. Thinner, insulated laminations act like rocks that break one big whirlpool into many tiny ripples. You still get flow yet the waste drops.

What does this mean for outboards.

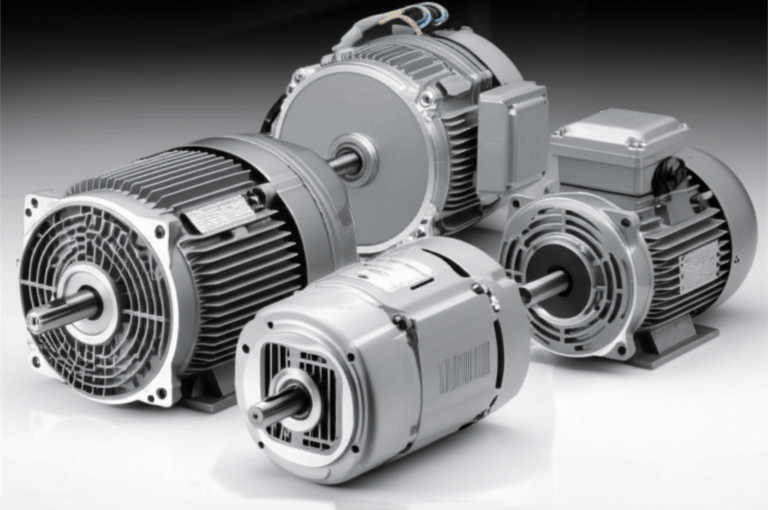

- Electric outboards: BLDC and PMSM machines live or die on efficiency, torque density, and thermal performance. Good motor core laminations push your copper and magnets to do useful work instead of heating the stator.

- Gasoline outboards: The alternator and starter motors also use laminated stator and rotor stacks. Better laminations improve charging performance at low RPM and cut heat under the cowl. That protects electronics and the ECU.

- Acoustic signature: Core losses and torque ripple affect noise and vibration. Better materials and optimized lamination geometry can cut NVH which matters on pontoons and fishing boats where a quiet ride sells.

- Weight and packaging: Higher grade steel and thinner gauges enable more compact motors at a given power. That matters in transom‑mounted packages where weight and balance affect trim, planing, and safety.

If you remember one thing remember this. Laminations let you trade material cost for operating efficiency and temperature. In long‑run duty cycles that trade often pays back quickly.

Your Options Explained: Lamination Materials and Manufacturing

Let’s guide you through the main choices. We’ll separate material considerations from manufacturing and assembly processes. The goal is to help you select based on application, volume, and cost targets.

Material considerations

- Non‑oriented silicon steels (CRNGO): The workhorse for rotating machines. Balanced magnetic properties in all directions make CRNGO a great fit for BLDC and PMSM motors in electric outboards and for alternators in gasoline outboards. You’ll see common thicknesses from 0.35 mm down to 0.2 mm or thinner for higher frequency. Thinner sheets reduce eddy currents yet raise cost and may complicate handling.

- Grain‑oriented silicon steels (CRGO): CRGO shines in transformers because it favors one magnetic direction. Rotating machines rarely use it for stators or rotors. Save CRGO for transformer cores in onboard chargers or shore‑power equipment.

- Cobalt alloys: Excellent at high flux densities and elevated temperatures. You pay a premium. Use them in aerospace or very high power density marine applications where every gram or degree counts.

- Advanced coatings: Each lamination gets an insulating coating that resists inter‑laminar currents. Choose based on thermal rating, punchability, and bond chemistry. Coating class matters if you plan to bond stacks during assembly.

- Stack factor: Real stacks include insulation and air gaps so the effective iron fraction of your stator core or rotor core matters. A higher stack factor improves your flux path without increasing overall dimensions.

If you want a quick refresher on the basics and options explore high quality overviews of electrical steel laminations.

Manufacturing and assembly processes

- Stamping: Ideal for high‑volume production. Progressive dies deliver tight tolerances, low burrs, and excellent repeatability. Tooling costs make sense when you scale.

- Laser cutting: Flexible and precise. You avoid tooling costs and move quickly on prototypes or low‑volume runs. Heat‑affected zones can raise losses so you manage cut strategy and post‑processing. Great for complex shapes and fast iteration.

- Waterjet and wire EDM: Niche options for special materials or when you need burr‑free edges without heat input. Slower and costlier on a per‑part basis.

- Interlocking and mechanical stacking: Think LEGO bricks. Tabs and notches snap laminations together to make a rigid core without welding. That keeps magnetic properties intact and speeds assembly.

- Bonding: Adhesive bonding or resin impregnation creates a solid stack with low vibration and good heat conduction. It also seals edges for corrosion protection in marine environments.

- Welding: Use sparingly on magnetic circuits. Welds introduce local losses. If you must weld choose locations with lower flux and control heat input.

You’ll specify tolerances for slot opening, tooth width, and skew. Skewed slots can reduce cogging torque and acoustic noise in BLDC motors which improves low‑speed trolling performance.

For deeper dives on the stator side review modern stator core lamination practices. When you need to balance back‑EMF, inductance, and thermal paths on the rotating side check rotor core lamination approaches for permanent magnet and induction designs.

Which Application Is This For? Matching Solutions to Boats and Business Goals

Different boats and business models lead to different answers. Let’s get practical.

- Small portable outboards under 25 HP: Weight, portability, and cost rule. Two‑stroke options once dominated. Today you’ll see compact four‑strokes and a growing number of small electric outboards with integrated batteries. Electric options win in lakes with strict environmental regulations and on tender duty where short hops and quiet operation matter.

- Mid‑range fishing boats and pontoons 25 to 150 HP: Four‑stroke gasoline outboards dominate with a wide range of horsepower ratings. You’ll care about fuel consumption, noise levels, and reliability. Electric trolling motors provide low‑speed thrust and precise control. Their stator and rotor stacks benefit from thinner laminations to cut eddy current loss at higher PWM switching frequencies.

- High performance offshore 150+ HP: Multi‑engine rigs want reliable power and serviceable gearcases. Electric main propulsion remains rare at these power levels today due to energy density limits. You still see electrification in auxiliary systems and hybrid concepts.

- Commercial and utility boats: Diesel outboards enter the picture where fuel logistics and safety demand diesel. Electric outboards grow in urban waterways with emissions standards and noise ordinances.

For procurement teams the decision expands beyond the motor. Consider lead times, warranty terms, CE certification needs for Europe, ABYC compliance for electrical systems, and U.S. Coast Guard equipment requirements. If you’re specifying an electric outboard or onboard alternator also align with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) small marine engine emissions standards and any local rules.

Honesty time. Laser cutting looks great in prototyping or complex low‑volume laminations. If you scale to tens of thousands of units with straightforward geometries stamping wins on cost and consistency. Bonded stacks feel solid and quiet yet you must align the adhesive and cure schedule with your coating class and oven capacities.

Outboards in Context: Outboard vs Inboard vs Sterndrive

Quick comparison helps frame the choice.

- Outboard vs inboard: Outboards live outside the hull which frees interior space and simplifies service. Inboards put the engine in the hull which can improve weight distribution and protect the powertrain. Inboards pair well with ski boats and some cruisers. Outboards excel in small to medium boats across many segments.

- Outboard vs sterndrive (I/O): Sterndrives split the difference. The engine sits inside and the drive unit hangs off the transom. You gain a clean swim platform with the drive trimmed down. Service access gets trickier. Outboards place the entire propulsion unit outside which simplifies installation and replacement.

A Brief History of Outboards

The modern outboard story starts with Ole Evinrude who commercialized practical outboards in the early 1900s. The Evinrude name became a fixture under BRP for decades. The market later consolidated around Mercury Marine, Yamaha Motor Co., Suzuki Marine, Honda Marine, and Tohatsu. Brunswick Corporation owns Mercury which anchors the U.S. share. Evinrude’s E‑TEC direct injection two‑strokes pushed emissions improvements early on. The industry then shifted heavily to four‑stroke technology. Today electric players like Torqeedo and powerful trolling motor brands like Minn Kota carry the electric banner. The next wave blends higher efficiency four‑strokes, better direct injection, and expanding electric options.

Cost, Maintenance, Reliability, and Environmental Considerations

Here’s how to think about the ownership side.

- Cost of outboard motors: Prices scale with horsepower, features, and brand. Portable units run modest. High‑performance multi‑hundred‑horsepower motors cost far more. Total cost of ownership includes fuel, oil, routine service, and depreciation.

- Fuel consumption and efficiency: Modern four‑strokes can be 30 to 50% more fuel efficient than older carbureted two‑strokes. Correct propeller pitch and gear ratio matter. Poor prop sizing wastes fuel and reduces top speed. Plan for cruising speed that sits in the engine’s efficient band.

- Reliability and durability: Big brands compete on durability in saltwater and freshwater. Pay attention to cooling system health, water pump impeller service intervals, and clean fuel delivery. Reliability improves when you follow a maintenance schedule and use quality fuel and oil types suitable for your engine.

- Repairs and diagnostics: External access simplifies repairs. Diagnostic tools connect to the ECU for fast fault isolation. Warranty terms vary. A clean service record supports resale value.

- Winterizing an outboard: If you store the boat in freezing climates you must winterize. Stabilize fuel. Fog the cylinders if needed. Change gearcase oil. Drain or protect the cooling system per the manual. Corrosion protection matters here too.

- Corrosion protection: Anodes protect in saltwater. Inspect the skeg and anti‑ventilation plate for damage. Rinse and flush with fresh water after every saltwater run.

- Emissions standards and noise: EPA and international rules shape combustion technology and catalysts. Electric outboards eliminate local emissions and cut noise dramatically. Some lakes require electric propulsion which accelerates adoption.

- Environmental impact: Better fuel efficiency and emissions control reduce impact on local air and water. Electric options pair nicely with renewable charging and help meet corporate sustainability goals.

- Compliance and safety: ABYC standards guide safe electrical systems and fuel setups. U.S. Coast Guard rules set carriage and safety gear requirements. CE certification matters for European markets.

Specifying an Outboard: A Practical Checklist

Use this checklist to avoid common pitfalls. It works for both gasoline and electric outboard motors.

- Boat and mission profile: Hull type, displacement, typical load, and target cruising speed. Add water sports, fishing, or utility tasks if relevant.

- Horsepower rating and torque: Match HP to hull and mission. Consider torque curves for holeshot vs cruising.

- Shaft length and transom height measurement: Verify with the actual hull. A short or long mismatch hurts performance and can cause ventilation.

- Weight of outboard motor: Check weight distribution and trailer tongue weight. Heavy motors change trim and handling.

- Propeller selection: Diameter and pitch to hit rated WOT RPM range with your typical load. Consider three vs four blades, material, and cupping.

- Steering mechanism: Tiller handle vs remote control. Hydraulic or electric assist for larger boats.

- Trim and tilt: Power trim saves arms and improves shallow water access. Make sure trim range matches hull behavior at planing speeds.

- Fuel system: Tank location, fuel type, filtration, and water‑separating filters. Carburetor vs fuel injection matters for cold starts and altitude changes.

- Electrical system: Alternator capacity for house loads, battery chemistry, isolation, and charging needs. For electric outboards plan battery capacity, voltage, BMS integration, and charger specs.

- Environment: Saltwater outboard features, anodes, and coatings. Freshwater models face different corrosion profiles.

- Compliance and documentation: EPA, ABYC, USCG, and CE certification as required. Keep NMMA data handy if you track market norms and resale.

- Service and warranty: Dealer network, parts availability, and warranty coverage. Factor downtime in commercial use.

- Diagnostics: ECU access and compatible diagnostic tools. Software updates and telemetry if available.

- Budget and total cost of ownership: Fuel or energy cost, maintenance schedule, and depreciation.

Your Engineering Takeaway

Here’s the short list you can carry into your next spec review or design meeting.

- Outboards are self‑contained propulsion units that bolt to the transom. They free interior space and simplify service.

- Four‑stroke gasoline outboards lead the market for noise, emissions, and fuel efficiency gains. Two‑stroke direct injection options still shine in power‑to‑weight sensitive roles.

- Electric outboard motors grow fast. They deliver quiet operation and zero local emissions. They rely heavily on efficient laminated stator and rotor cores to hit performance targets.

- Match horsepower, shaft length, and propeller pitch to your hull and mission. Get transom height measurement right or you’ll leave performance on the table.

- Maintenance is straightforward. Pay attention to cooling systems, water pump impellers, gearcase seals, and anodes for corrosion protection.

- For engineers working on electric outboards or alternators, lamination choices matter. Thinner insulated sheets cut eddy currents. Material selection balances cost, losses, and temperature rise.

- Manufacturing choices follow volume and geometry. Stamping dominates high volume. Laser cutting suits prototypes and complex low‑volume parts. Bonded or interlocked stacks reduce NVH without hurting magnetic performance.

If you want to continue your lamination deep dive review the fundamentals and application notes for motor core laminations plus stator and rotor specifics. That background will make your next conversation with a lamination supplier far more productive.

And if you’re in early design on an electric outboard program you can benefit from a quick pass through stator core lamination and rotor core lamination. Those pages outline practical considerations like stack factor, insulation coatings, and skew that directly affect efficiency and NVH in marine duty.

Finally if you need a primer on material options and coating classes for rotating machines scan the overview of electrical steel laminations so you can weigh CRNGO grades and thickness choices with confidence.

Sources and notes

- NMMA industry data shows outboards at roughly 85% of new powerboat engine sales in the U.S. in 2022.

- Market size estimates from firms like Mordor Intelligence and Grand View Research place the global outboard motor market near $11B in 2023 with mid‑single‑digit CAGR projections through the early 2030s.

- Manufacturer specifications and published comparisons indicate modern four‑stroke outboards reduce fuel burn 30 to 50% vs legacy carbureted two‑stroke models with notable reductions in noise levels.

If you want a sanity check on your current spec or a second set of eyes on the lamination stack that sits at the heart of your electric outboard drop your questions. I’m happy to help you weigh trade‑offs and pick a path that keeps your performance, budget, and timeline all on plane.