What Does a Starter Motor Do? Your Car’s Essential Engine Ignition Explained

Meta description: Discover what a starter motor does and why it matters. See how electrical and mechanical design—especially motor laminations—drive performance, reliability, and cost. Learn the components, failure symptoms, diagnostic tips, and how to pick the right lamination materials and manufacturing processes.

Every product designer and procurement team has faced this question from a different angle. A driver asks why the car won’t start. An engineer asks why the starter’s current draw is high and torque still lags. A purchasing lead asks why this starter costs more than the last one. The same component sits at the center of all three threads. The starter motor.

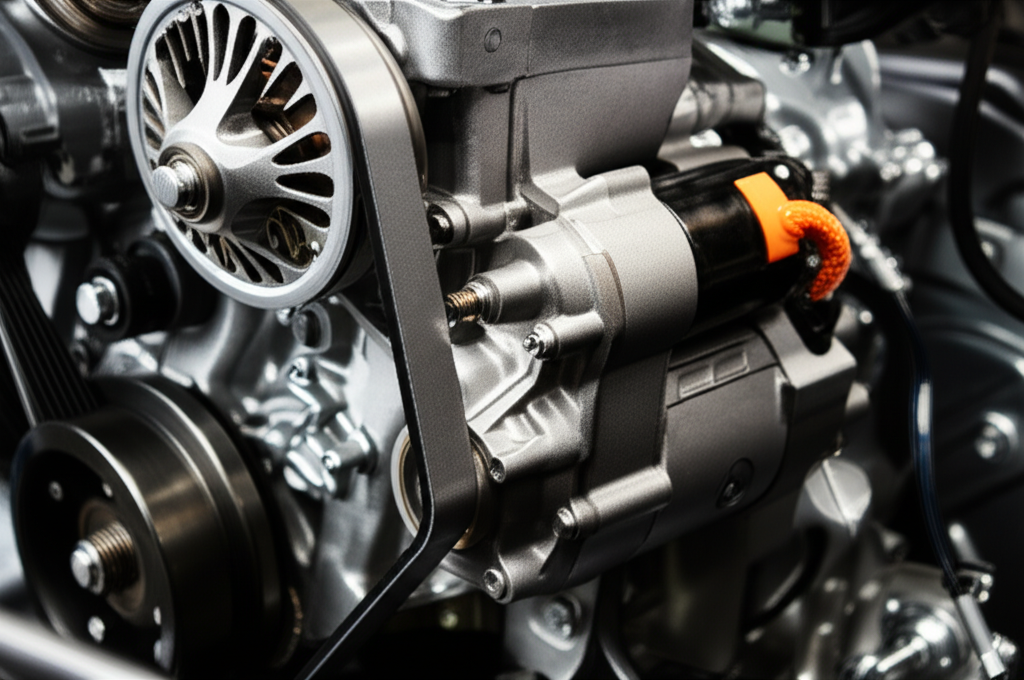

Here’s the core problem. The internal combustion engine can’t start on its own. It needs a strong, short burst of mechanical power to turn the crankshaft past compression. The starter motor supplies that burst. When it works you don’t think about it. When it fails your whole product looks bad.

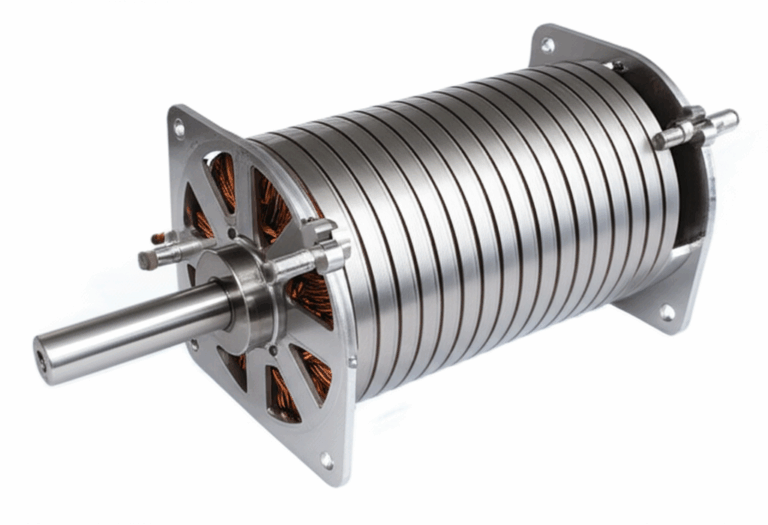

The engineering truth under the hood is simple yet subtle. A starter is a high-torque DC motor with a solenoid and a pinion gear that engages the flywheel’s ring gear. It must deliver serious torque at low speed for a few seconds. It must do it over and over in heat, cold, and grime. That’s a tough brief. The heart of meeting it lies in the electromagnetic steel, the lamination stack design, and the manufacturing process you choose.

Below you’ll find the fundamentals, the practical symptoms, the diagnostics, and the material and process choices that drive real-world outcomes. We’ll stay clear, direct, and actionable.

In This Article

- The Starter Motor’s Core Function: Giving Your Engine Life

- How a Starter Motor Works: Step-by-Step Ignition Process

- Key Components of a Starter Motor: The Parts That Make It Work

- Why Your Vehicle Can’t Start Without a Functional Starter Motor

- Common Symptoms of a Failing Starter Motor: What to Listen For

- Troubleshooting Starter Motor Issues

- Lifespan and Maintenance Considerations

- Engineering Fundamentals: Laminations, Core Losses, and Torque

- Your Options Explained: Materials and Manufacturing for Starter Motor Laminations

- Which Application Is This For? Best-Fit Choices by Use Case

- Data and Specifications at a Glance

- Engineering FAQs

- Your Engineering Takeaway

The Starter Motor’s Core Function: Giving Your Engine Life

A starter motor is a compact, high-torque electric motor that cranks the engine so combustion can begin. It takes electrical power from the 12V battery and converts it into mechanical rotation. Think of it like a kick-start for the engine. Without that first push the internal combustion engine won’t run because it cannot self-start from a stop.

Why it’s essential:

- It overcomes static friction, compression, and pumping losses.

- It spins the crankshaft fast enough to draw in air, compress it, and ignite fuel.

- It bridges a design catch-22. The engine needs to be spinning to create power. It needs power to start spinning.

How a Starter Motor Works: Step-by-Step Ignition Process

The Starting Sequence: From Key Turn to Engine Roar

- It pushes the pinion gear forward.

- It closes a high-current contact that powers the motor.

Mechanical and Electrical Harmony

The starter’s geometry and electromagnetic design must work in lockstep. The motor must deliver high peak current and high torque for a short duty cycle. Mechanical elements like the Bendix drive, the ring gear, and the overrunning clutch must engage cleanly under load. Electrical elements like brush contact, commutator segments, and the steel lamination stack must minimize loss while supporting a sharp torque rise.

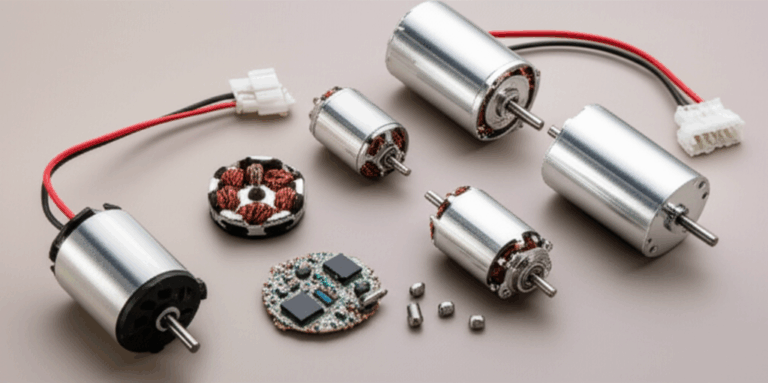

Key Components of a Starter Motor: The Parts That Make It Work

- Solenoid: An electromechanical relay and actuator. It slides the pinion into the ring gear and closes the high-current circuit.

- Electric motor: A series-wound or permanent magnet DC motor with armature, brushes, commutator, and field windings or magnets. It converts electrical energy to mechanical rotation.

- Bendix drive and pinion gear: A helical mechanism that aids engagement with the flywheel ring gear. Some designs use gear-reduction starters for better torque density.

- Overrunning clutch: Allows the pinion to freewheel once the engine fires. It prevents the engine from over-spinning the motor.

- Housing: A robust enclosure that supports bearings and shields electrical parts from heat and debris.

- Electrical interface: Heavy power cable, ground wire, Terminal 30 for battery power, Terminal 50 for solenoid activation, and sometimes a starter relay in the circuit.

Inside the motor, the steel lamination stack—both armature and stator—sets magnetic performance. Laminations reduce eddy current losses. They keep heat down. They preserve torque in those critical few seconds of cranking.

Why Your Vehicle Can’t Start Without a Functional Starter Motor

An internal combustion engine needs motion to pull in air and compress the mixture. Yet it has no motion at a stop. The starter motor bridges that gap by forcing the first few revolutions. It turns the crankshaft so the ignition coil, spark plugs, and fuel pump can do their jobs. No starter means no crank. No crank means no combustion. No combustion means no start.

Common Symptoms of a Failing Starter Motor: What to Listen For

These symptoms often surface when drivers search “car won’t start” or “why won’t my car start.” They also guide engineers and technicians during validation and diagnosis.

- Clicking noise: A sharp solenoid click with no crank can point to low battery voltage, a high-resistance connection, or a failing solenoid.

- Slow cranking: The engine cranks slowly. You hear labored rotation. The battery might be weak. The starter could have worn brushes, a bad commutator, or high internal resistance.

- Grinding noise on start: Grinding or screeching indicates poor pinion engagement with the flywheel ring gear. It can damage both gears.

- Free-spinning starter: The motor spins with a whine but the engine doesn’t turn over. The pinion may not be engaging or the overrunning clutch may be slipping.

- No noise or no crank: Total silence usually points to a dead battery, a failed ignition switch, a bad starter relay, an open circuit, or a failed starter solenoid.

- Smoke or burning smell: Overheating from a short, a locked rotor, or extended cranking creates smoke and odor. Stop and diagnose.

- Intermittent starting: Works sometimes then fails. Check loose connections, corroded terminals, the neutral safety switch, or heat-soak issues.

Related terms you may see in service notes:

- Engine cranking and turning over the engine refer to the same event. The crankshaft rotates due to the starter.

- Hot start and cold start can stress different failure modes. Heat raises resistance. Cold thickens oil and raises torque demand.

- Starter whine, starter grind, and screeching noise from starter describe different acoustic clues.

- Starter motor noise changes as brushes wear and as gears lose alignment.

Troubleshooting Starter Motor Issues

Start simple then work toward the motor.

- Differentiate from a dead battery: Check battery voltage at rest and under load. A healthy battery reads about 12.6V at rest. During crank it can dip but not collapse. A jump start is a quick field test, although it’s not a full diagnosis.

- Look for voltage drop: Measure voltage at the starter during cranking. Significant drop along the power cable or ground path points to high resistance. Clean corroded terminals. Check the ground strap to the chassis.

- Check the starter circuit: Inspect the ignition switch, starter relay, and Terminal 50 control wire. Look for open circuits, damaged wiring harness sections, or a neutral safety switch signal issue on automatic transmissions.

- Perform a starter current draw test: High draw with slow cranking can indicate internal binding or shorted windings. Low draw with no crank can indicate an open circuit or poor engagement.

- Inspect mechanical engagement: Listen for grinding. Check for damaged teeth on the flywheel ring gear. Assess the Bendix drive, gear reduction mechanism on gear reduction starters, and the overrunning clutch.

- Confirm other engine systems: The starter can crank yet the engine won’t run. That points to fuel pump, ignition coil, spark plugs, or compression issues.

When to call a professional mechanic:

- You see smoke, smell burning, or hear metal-on-metal grinding.

- Voltage and current tests show internal motor faults.

- The starter is buried and difficult to access on your vehicle.

Lifespan and Maintenance Considerations

Typical lifespan:

- 80,000 to 150,000 miles or 5 to 10 years for many passenger vehicles.

Major drivers of life:

- Frequent starts increase wear. City delivery vehicles and start-stop systems cycle starters more often.

- Climate matters. Heat raises electrical resistance. Cold increases torque demand due to thicker oil.

- Electrical health matters. A weak battery or high resistance in cables forces the starter to work longer and hotter.

Cost and service:

- Average replacement cost ranges from roughly $300 to $600 total depending on the vehicle. Parts range from about $50 to more than $400. Labor varies by access and region.

- Starters are usually replaced rather than repaired in the field. You can extend life by maintaining a healthy battery and clean terminals.

Voltage and current:

- Operating voltage is 12V DC for most passenger cars. Some trucks and heavy equipment use 24V systems.

- Peak current draw ranges from about 100A to 600A. Cold conditions, engine size, and compression drive that number.

Common failure causes:

- Worn brushes reduce contact and torque.

- Solenoid failure prevents engagement or current flow.

- Damaged gears cause grinding and poor engagement.

- Electrical shorts or opens in windings or cables.

- Bearing failure leads to drag and electrical overload.

Warranty:

- Many new or remanufactured starters carry 1 to 3 year warranties.

Engineering Fundamentals: Laminations, Core Losses, and Torque

Here’s where design teams win or lose the battle for efficient cranking.

Why laminations:

- Eddy currents: A changing magnetic field induces circular currents in solid steel that create heat and waste energy. Laminations break those loops into tiny paths. Less current flows. Less heat forms. More of your battery power becomes torque.

- Hysteresis loss: As the steel’s magnetic domains flip direction they dissipate energy as heat. Lower coercivity reduces this loss. The B-H curve tells you how easily a material magnetizes and demagnetizes.

An analogy that sticks:

- Picture eddy currents as whirlpools in a river. A solid block of steel lets big whirlpools form. Laminations with insulation act like a net of barriers that break those whirlpools into small ripples. Smaller ripples waste less energy.

Key parameters:

- Lamination thickness: Thinner laminations reduce eddy currents. They do cost more to stamp and handle.

- Electrical steel grade: Silicon content, grain orientation, and coating class all influence loss and permeability.

- Permeability: Think of it as how easily the material lets magnetic flux pass through. High permeability helps you get torque efficiently.

- Coercivity: It’s the material’s resistance to demagnetization. Lower is better for reducing hysteresis loss.

- Insulation coating: It sets interlaminar resistance. It also affects stacking factor and thermal performance.

Starter-specific context:

- Starters operate at low mechanical speed with high torque for short bursts. Frequencies in the steel are modest compared to high-speed motors. You still need laminations to curb eddy currents under high current. You also need a robust stack that won’t shift during vibration and shock.

If you want to dig deeper into foundational material options you can review typical electrical steel laminations. That overview gives you a sense of coating classes, thickness ranges, and use cases.

Your Options Explained: Materials and Manufacturing for Starter Motor Laminations

Material considerations:

- Non-oriented silicon steels (CRNGO, often called M-grades): The workhorse choice for many DC motors. They balance cost and performance. Good for general-purpose starters with moderate frequencies and short duty cycles.

- Pros: Widely available, cost-effective, consistent performance.

- Cons: Higher core loss than premium alloys at high frequency. Usually acceptable in starters.

- Grain-oriented silicon steels (CRGO): Optimized for one flux direction. They excel in transformers with unidirectional flux. Starters experience rotating fields in the armature, so CRGO rarely fits.

- Pros: Low core loss in the preferred direction.

- Cons: Not ideal for rotating machines with varying flux direction.

- Cobalt-bearing alloys: Very high saturation and strength for extreme power density. Aerospace and specialty high-temperature solutions use them. Most automotive starters won’t justify the cost.

- Pros: High flux density margins and thermal resilience.

- Cons: Expensive and harder to process.

- Permanent magnet vs wound-field: Field structure shifts lamination requirements. PM starters still use laminated armatures to control losses. Series-wound starters use laminated stators and armatures.

Manufacturing and assembly processes:

- Progressive-die stamping: The go-to process for production volumes. It offers tight tolerances, good burr control, and low cost at scale. It requires upfront tooling investment.

- Laser cutting: Ideal for prototypes or low volumes. It offers flexibility and quick changes. Heat-affected zones can influence edge loss and stacking factor so you must tune process parameters.

- Wire EDM: Very precise for difficult geometries. Slower and more expensive. Use it when tolerances matter more than speed.

- Interlocking laminations: Tabs and notches snap together like LEGO bricks. You avoid welding and keep magnetic properties intact. Great for high-volume stacks.

- Bonding and varnish: Adhesive bonding reduces vibration and noise. It also stabilizes the stack and improves thermal paths.

- Welding: Strong but risky for magnetic properties if done poorly. Use carefully with fixtures and process controls.

Where the laminations live in a starter:

- Stator side: In wound-field starters the pole pieces use laminated stacks. In PM starters the stator often uses magnets attached to a steel shell. The shell can include laminated back-iron in some designs. See what matters most in a stator core lamination.

- Rotor side: The armature core always uses laminations on a shaft. Slots hold the windings. The commutator sits on one end. Precision matters here for balance and slot geometry. Explore a typical rotor core lamination.

Tie the design to procurement:

- Define the lamination thickness, insulation class, and stacking factor explicitly in drawings.

- Specify acceptable burr height and edge quality. These influence iron loss and mechanical integrity.

- Call out assembly method: interlock, bonding, rivets, or welds.

- Align tolerances with the winding process and slot fill targets. High slot fill helps torque yet raises thermal density.

If you’re benchmarking or sourcing across multiple motor types you can compare broader motor core laminations to see how base principles carry over into BLDC stator cores, induction rotors, and transformer laminations.

Which Application Is This For? Best-Fit Choices by Use Case

Automotive gasoline engines:

- Typical 12V systems with short duty cycles. CRNGO silicon steel with moderate lamination thickness often balances performance and cost.

- Interlocking or bonded stacks withstand vibration. Gear reduction starters help reduce current draw and improve cold cranking.

Diesel engines and heavy trucks:

- Higher compression raises torque demand. 12V passenger diesels or 24V heavy equipment require stronger gear reduction and robust armature stacks.

- Choose higher saturation materials and tighter burr control. The duty cycle may be longer during glow plug waits and cold starts.

Start-stop systems:

- Frequent cycling increases mechanical and thermal fatigue. Reinforce bonding and improve brush materials. Reduce core losses to manage heat during repeated short bursts.

Extreme climates:

- Cold increases cranking torque. Hot increases electrical resistance. Material stability and insulation class matter. Seals and coatings fight corrosion.

Prototyping and rapid iteration:

- Laser cutting accelerates design loops. Watch heat-affected zones and adjust thickness or coating as needed. Transition to stamping for cost at scale.

High-reliability fleets:

- Delivery vehicles take relentless cycles. Invest in improved brush grades, higher interlaminar insulation, and bonded stacks. You pay a bit more up front to avoid vehicle downtime later.

Be honest about limitations:

- Laser cutting offers precision for complex geometries and prototypes. Stamping usually beats it in cost and consistency for high volumes.

- Cobalt alloys deliver power density. They rarely pencil out for mainstream automotive starters.

Data and Specifications at a Glance

Use these ranges as planning guardrails. Confirm with your supplier and your validation data.

- Typical lifespan: 80,000 to 150,000 miles or 5 to 10 years.

- Average replacement cost: About $300 to $600 total. Parts range $50 to $400+. Labor depends on access and shop rate.

- Operating voltage: 12V DC for passenger vehicles. 24V in some trucks and equipment.

- Current draw: About 100A to 600A on initial engagement depending on engine size, temperature, and design.

- Common failure causes: Worn brushes, solenoid failure, damaged gears, electrical shorts or opens, and bearing failure.

- Warranty: Often 1 to 3 years for new or remanufactured units.

- Impact of frequent starts: Wear rises on brushes, Bendix, and gear train. Start-stop and delivery cycles demand stronger designs.

Engineering FAQs

Is the starter a DC motor or something else?

- It’s a DC motor. Most are brushed series-wound designs for high starting torque. Some use permanent magnets for the field.

What’s the difference between a starter and an alternator?

- The starter converts electrical energy to mechanical energy for a short burst. The alternator converts mechanical energy back to electrical energy to charge the battery while the engine runs.

What is a gear reduction starter?

- It uses a small high-speed motor with a reduction gear set to boost torque at the pinion. You get better torque density and often lower current draw.

How do Terminal 30 and Terminal 50 figure into diagnostics?

- Terminal 30 brings battery power to the starter. Terminal 50 carries the solenoid activation signal. Verify both during crank to separate control issues from power issues.

What about brushless starters?

- Brushless designs exist in integrated starter-generators and some advanced systems. Classic stand-alone starters in most vehicles remain brushed.

How do laminations help with such a short duty cycle?

- Even short bursts create changing magnetic fields. Laminations cut eddy current loss and heat so more battery energy turns into torque.

Who manufactures automotive starters?

- Many well-known suppliers produce starters including Bosch, Denso, Valeo, ACDelco, and Delco Remy among others.

The Starter Motor Through the Diagnostic Lens

If you’re writing a troubleshooting guide or designing an on-board diagnostic routine keep these checkpoints in mind. They mirror the way technicians think while they distinguish starter vs battery vs wiring issues.

- Car won’t start but lights work: Check voltage drop during crank. High drop suggests cable resistance or an internal starter problem.

- Car makes clicking noise: Often the solenoid clicks without full engagement due to low voltage or a weak battery. Verify with a multimeter and a starter current draw test.

- Engine cranks slowly: Look at battery state of charge, cable resistance, and brush wear. Slow cranking can also point to high engine friction in cold weather.

- No noise or no crank: Check the ignition switch, starter relay, neutral safety switch, and fuses. Confirm an intact ground.

- Grinding noise on start: Inspect the flywheel ring gear and pinion alignment. Look at Bendix drive health and mounting position.

- Intermittent starting: Heat soak can cause high resistance. Loose connections and corroded terminals also play a role.

- After battery replacement the car still won’t start: Confirm the terminals are tight and clean. Check the starter circuit and the solenoid.

You can summarize the car ignition sequence like this: ignition switch or push-button start sends an ignition signal, starter relay and solenoid act, power flows from the battery, the pinion gear engagement happens, the engine cranking begins, and the engine catches once fuel and spark join. That’s the car ignition sequence in a nutshell.

A Few Design Notes on Current, Torque, and Thermal Limits

- Torque constant and copper: Higher copper fill in the armature slots increases torque per amp. It raises thermal density too. Balance winding fill against allowable temperature rise during cold crank.

- Saturation margin: Pick an electrical steel grade that stays below saturation at peak current. Saturation reduces torque gains and wastes energy as heat.

- Brushes and commutator: They set current transfer capability. Brush grade and spring force matter for cold starts and high vibration.

- Bearings and alignment: Misalignment raises friction. It steals torque and raises current draw.

- Overrunning clutch: It must disengage fast once the engine fires. Failure causes screeching noise from the starter and rapid wear.

Procurement Checklists That Save Time

- Material: Grade, thickness, and insulation class clearly specified. Include target core loss at a test flux density and frequency relevant to your use case.

- Geometry: Slot details, burr limits, and stacking factor stated with inspection criteria.

- Assembly: Interlock tab spec, bonding adhesive type, or weld callouts with heat control plan.

- Electrical: Resistance and inductance of the armature windings with tolerance. Brush grade and commutator spec.

- Validation: Cold crank torque, current draw at defined temperatures, cycle life targets, and environmental test plans.

Work these into your RFQs to avoid surprises later. Your supplier will thank you.

Where Starter Design Meets System-Level Reliability

The starting system isn’t just a motor. It’s a circuit and a mechanism.

- Car electrical system: The battery, alternator, fuses, relay, wiring harness, and ground path set the starter’s environment. A strong alternator keeps the battery ready. A weak alternator creates a slow decline that ends with a no-start complaint.

- Controls: The ignition switch and immobilizer or keyless entry system decide when the starter can operate. A remote start system adds logic and timing.

- Safety: The neutral safety switch prevents crank in gear. It reduces surprises.

- Diagnostics: Voltage drop test and current draw test with a multimeter catch most faults without tearing the car apart.

End-User Experience Matters

Drivers don’t care about lamination thickness. They care about whether the engine cranks confidently on a cold morning. You control that experience with choices upstream—steel grade, slot geometry, bonding method, and QC on burrs and insulation. Small details flip user sentiment from “car starts slow” to “car starts strong.”

Your Engineering Takeaway

- The starter motor converts 12V battery energy into a high-torque burst that turns the crankshaft and initiates combustion.

- Clean mechanical engagement matters. The solenoid, Bendix drive, pinion gear, ring gear, and overrunning clutch must cooperate under load.

- Laminations are not an afterthought. They cut eddy current and hysteresis losses so more current becomes useful torque rather than waste heat.

- Material selection is contextual. CRNGO silicon steels fit most starter use cases. Cobalt alloys are overkill for mainstream designs.

- Manufacturing process drives cost and performance. Stamp for volume. Laser cut for prototypes. Use interlocks or bonding to stabilize stacks and reduce noise.

- Diagnostics follow a pattern. Separate battery, wiring, and starter faults with voltage drop and current draw tests.

- Life and cost vary. Many starters last 80k to 150k miles. Replacement commonly runs $300 to $600 depending on access and parts choice.

- Align engineering and procurement early. Specify lamination thickness, insulation class, stacking factor, and assembly method to avoid late-stage surprises.

If you’d like a structured overview of lamination families for rotating machines you can scan examples of motor core laminations. The stator and rotor examples above show where tolerance, coating, and assembly decisions move the needle in a starter.

Ready for next steps?

- Define torque, current, and duty cycle targets at your cold-crank worst case.

- Lock a lamination material and thickness range that stays below saturation at peak current.

- Pick a manufacturing path—stamping or laser—based on volume and geometry.

- Call out interlock or bonding so the stack stays tight under vibration.

- Align test plans to validate cold and hot start, intermittent starting, and long-term wear.

When you do that you’ll walk into your supplier review with confidence. You’ll get a starter that cranks hard, runs cool, and keeps customers out of the “car won’t start” line.

Notes on trusted references and standards:

- IEC 60034 covers rotating electrical machines at a high level.

- ASTM standards such as A677 cover nonoriented electrical steel specifications.

- IEEE transactions and industry handbooks discuss DC motor design, core losses, and steel grades in more depth.

If you need support translating targets into lamination drawings, slot geometry, or process controls, bring your torque and current curves and we’ll turn them into clear specs.