What is a Car Starter Motor? Your Complete Guide to How it Works, Symptoms, & More

Every design engineer and procurement lead shares the same first principle. You need robust starts, predictable costs, and a clear path to scale. Whether you’re sourcing a starter motor for a heavy-duty diesel, optimizing a gear reduction starter for smaller packaging, or simply trying to understand why a vehicle shows a slow crank no start in cold weather, you’re in the right place.

We’ll answer two connected questions. First, what does a starter motor do in day-to-day automotive use. Second, how do motor laminations, materials, and manufacturing choices influence torque, heat, cost, and reliability. If you need a quick definition, a car starter motor is a high-torque electric motor that cranks the engine so it can begin combustion. If you need a practical guide, keep reading. You’ll get a step-by-step explanation of the engine cranking mechanism, an engineer’s view of the components that matter, and a procurement-ready overview of options, trade-offs, and costs.

Before we dive in, here’s a fast roadmap.

In This Article

- The Core Function: Getting Your Engine Started

- How a Car Starter Motor Works: A Step-by-Step Explanation

- Anatomy of a Starter Motor: Internal & External Components

- Common Types of Starter Motors

- Signs and Symptoms of a Failing Starter Motor

- Troubleshooting Starter Motor Problems (Basic Diagnosis)

- Starter Motor Maintenance and Lifespan

- Starter Motor Replacement: When & What to Expect

- Materials and Manufacturing for Design Teams: Laminations, Losses, and Processes

- Which Application Is This For? Matching Design Choices to Use Cases

- Your Engineering Takeaway

The Core Function: Getting Your Engine Started

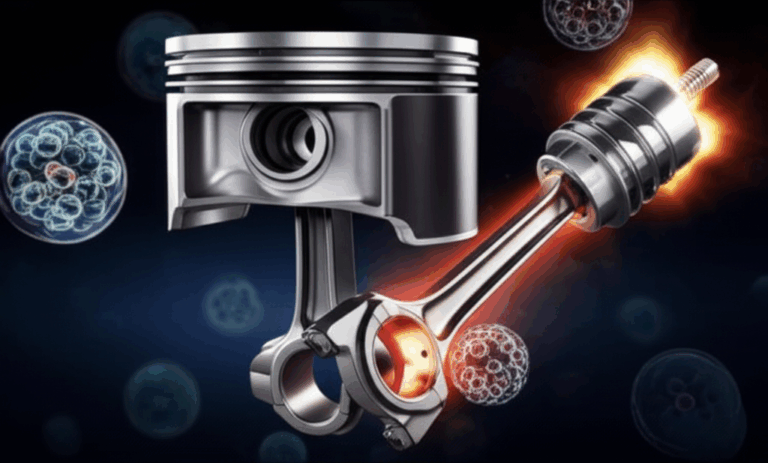

Internal combustion engines won’t start themselves. They need an initial push. The starter motor delivers that push with torque at low RPM so the engine can draw in air and fuel then fire. In technical terms, the starter motor converts electrical energy from the car battery into mechanical rotation. That rotation turns the flywheel ring gear which spins the crankshaft. Once the engine runs on fuel, the starter disengages.

Think of the whole automotive starting system as a carefully choreographed sequence. The ignition switch energizes the starter relay. The relay triggers the starter solenoid. The solenoid engages the pinion gear into the flywheel and also closes high-current contacts that feed the motor. The motor produces torque through its armature windings and field coils or permanent magnets. The engine fires then the solenoid retracts the Bendix drive so the pinion gear pulls back.

That’s the simple version. Now let’s look under the hood and see how each piece works.

How a Car Starter Motor Works: A Step-by-Step Explanation

The Ignition Sequence: From key turn to engine crank

- You turn the key cylinder or press the start button. The ignition switch sends a low-current signal to the starter relay.

- The starter relay closes and sends battery voltage to the starter solenoid S terminal.

- The solenoid plunger moves. This action does two things at once. It pushes the Bendix drive so the pinion gear meshes with the flywheel ring gear. It also closes the solenoid’s high-current contactor so the motor gets full battery power at the M terminal.

- The motor draws a large current. It produces torque and spins the engine. Typical current draw for a car starter sits in the 100–200+ amp range. Big diesels can demand much more cranking amps.

- As the engine fires and outruns the pinion gear, the overrunning clutch in the Bendix drive allows the pinion to freewheel. The solenoid then retracts the pinion. The motor stops.

Key Components in Action

- Starter Solenoid: The solenoid acts as a heavy-duty switch and a mechanical actuator. It handles two roles. It switches high current to the motor and it engages the pinion gear. Inside, a plunger moves under magnetic force and bridges the high-current contacts. If the solenoid plunger sticks or the contactor pits, you get intermittent starting problems, single clicks with no crank, or no crank no start issues.

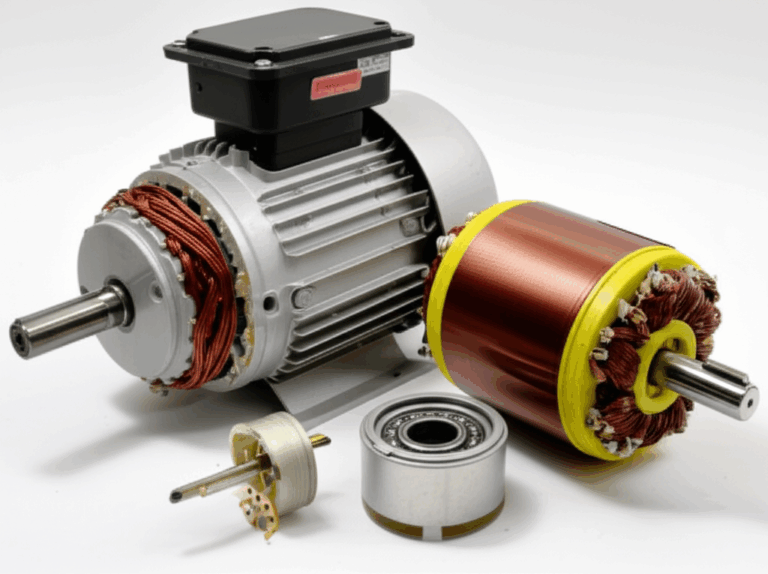

- Electric Motor: Most automotive starters are series-wound DC motors. You’ll see an armature with windings on a laminated iron core, field coils or permanent magnet fields inside the starter housing, a commutator, and carbon brushes. Series winding gives high starting torque at low speed which is exactly what you want for engine cranking.

- Bendix Drive (Overrunning Clutch): This assembly slides the pinion gear into the flywheel during engagement and protects the motor once the engine fires. The overrunning clutch lets the pinion freewheel so the engine doesn’t spin the motor like a generator.

- Pinion Gear: Small but crucial. The pinion gear engages the flywheel ring gear. Damaged pinion teeth cause grinding noise when starting and can chew up the flywheel.

- Flywheel Ring Gear: The big gear on the flywheel or flexplate. It receives torque from the starter. Worn or missing teeth cause intermittent no crank when the engine stops in that spot.

The Power Source: The role of the car battery

The car battery supplies high current at around 12 V nominal. If the battery is weak or if battery terminal corrosion increases resistance, the starter will crank slowly or you’ll hear a click. Low voltage under load mimics many symptoms of bad starter motor problems. Always check battery state of charge and voltage drop before you condemn the starter motor.

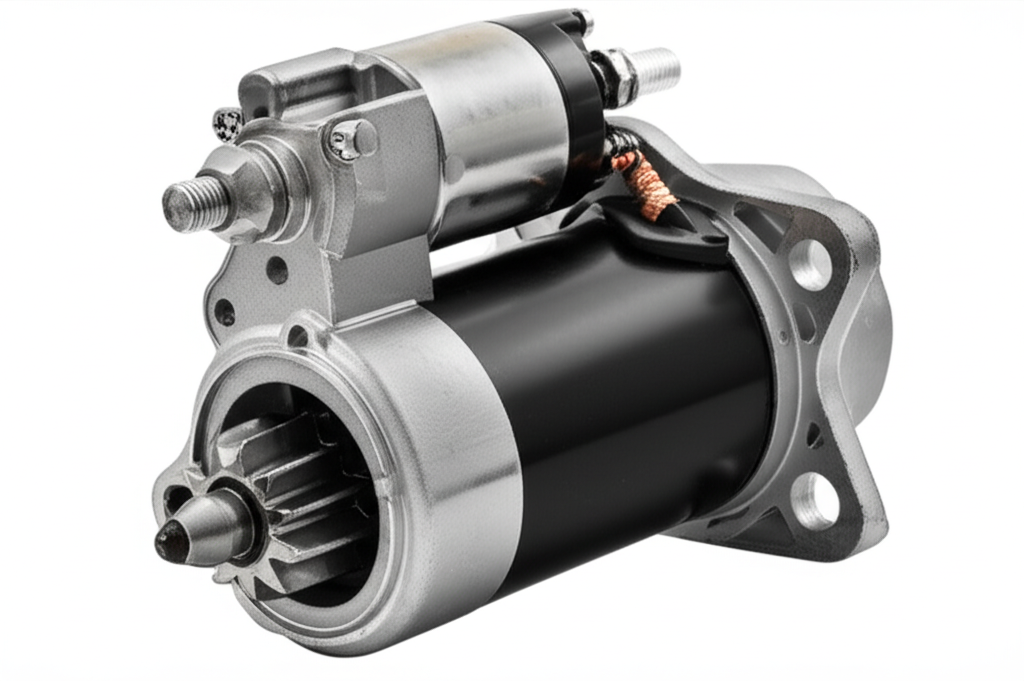

Anatomy of a Starter Motor: Internal & External Components

Main Internal Parts

- Armature: The rotating core with armature windings. It sits on bearings and connects to the commutator. Laminated steel discs make up the core to control eddy current loss.

- Field Coils or Permanent Magnets: They create the magnetic field in the starter housing. Traditional starters use field coils with series winding. Newer compact designs often use permanent magnets.

- Brushes (Carbon) and Commutator: Brushes ride on the commutator segments. They switch current through the armature windings in sync with rotation. Worn brushes and a pitted commutator often cause slow crank, intermittent starting, or no crank.

- Overrunning Clutch and Pinion: Part of the Bendix drive. It transmits torque one way and freewheels the other.

- Bearings/Bushings: Support the armature shaft. Excessive wear can cause armature drag which leads to high current draw and overheating starter motor.

External Parts & Connections

- Starter Housing and Mounting Points: The shell supports everything and bolts to the engine block. Proper alignment matters for quiet engagement with the flywheel.

- Starter Solenoid: Usually mounted on the housing. It contains the plunger and the high-current contactor.

- Electrical Terminals: B+ (battery), S (solenoid control), and M (motor). Clean terminals prevent voltage drop.

- Battery Cables and Ground Cable: Heavy-gauge battery cable feeds the starter. The ground returns current to the battery via the engine block and chassis. Loose wiring or a poor ground wire for starter causes slow or no crank.

- Neutral Safety Switch, Fuses, and the Starter Relay: These protect and control the starting circuit. The neutral safety switch prevents cranking when the transmission is in gear.

The lamination core inside a starter motor

Here’s where motor laminations matter. The armature core and, in some designs, pole pieces in the field path use stacked, insulated laminations. The goal is simple. Reduce eddy currents and hysteresis loss then push more of your battery current into usable torque.

- Why laminations: A changing magnetic field induces currents in iron. Those currents circulate and heat the core which wastes energy. Laminations break up the path into thin slices. Each slice has an insulating coating so eddy currents stay small.

- Material basics: Most starter cores use non-oriented silicon steel grades designed for rotating machinery. You’ll see thicknesses commonly in the 0.35–0.5 mm range for motors though selections vary by design, frequency content, and cost.

- Coatings: Organic or inorganic insulation on each lamination controls interlaminar resistance. The coating must survive stamping and stack assembly without cracking.

- Stack assembly: Interlocking features, rivets, cleats, bonding adhesives, or light welding can form the armature stack. Heat from welding can degrade magnetic properties so engineers choose process and location carefully.

If you want a deeper dive on materials and stack construction, these resources can help:

- Learn how different stack builds influence magnetic path and torque in motor core laminations.

- Explore base material choices and coatings across electrical steel laminations.

- See how grade and thickness within silicon steel laminations affect eddy current loss and cost.

- Understand the role of both the stator core lamination and the rotor core lamination in motor design. Starters use a laminated rotor and field path that follow similar principles.

Common Types of Starter Motors

Direct drive starter motor

Older designs use a direct drive starter. The motor’s pinion gear directly meshes with the flywheel ring gear. These starters are robust but larger and heavier. They demand very high current under load which can stress the electrical system in cold cranking.

Gear reduction starter

A gear reduction starter uses a small, high-speed motor plus a planetary gearset to multiply torque at the pinion. You get more torque in a smaller package and improved efficiency. Gear reduction starters are now common. They shine in high-compression engines and start-stop systems where frequent cycling happens.

Permanent magnet starter

Permanent magnet starters replace field coils with permanent magnet fields. They reduce size and improve efficiency since you don’t waste current energizing field coils. They pair well with gear reduction designs. They do not like sustained overheating or mechanical shock so housing and support design matter.

Windings and magnetic circuit choices

- Series winding: Delivers high starting torque at low speed which is typical in automotive starting systems.

- Shunt winding: Offers steadier speed under load but lower torque at stall. It shows up less in modern starters yet remains a concept worth knowing.

- Armature and field design: Field coils, armature windings, commutator geometry, and brush layout decide torque-to-current behavior. Permanent magnet starter designs shift some of these trade-offs into the magnet material selection and the lamination geometry.

Signs and Symptoms of a Failing Starter Motor

You’ll often hear these in the service bay. The starter motor clicks but the car won’t start. Or you hear a grinding sound starter condition after the engine fires. Let’s decode the common symptoms of bad starter motor issues.

Clicking noise with no crank

A single loud click suggests the solenoid pulls in but the motor doesn’t spin. Causes include a weak car battery, corroded battery terminal connections, a bad solenoid contactor, or a shorted armature. Rapid repeating clicks often point to low voltage under load. Ask yourself first. Can a bad battery mimic bad starter The answer is yes.

Slow or sluggish cranking

If the engine turns over slowly or you see dim dashboard lights when starting, suspect high resistance in the starter circuit. Battery health, a worn starter motor, a dragging armature bearing, or poor ground can cause it. Freezing weather starter issues exaggerate this since cold oil increases engine drag.

Grinding noise when starting

This is the classic pinion gear and flywheel ring gear engagement problem. Misalignment, a damaged pinion, or worn flywheel teeth cause a grinding noise when cranking or a starter motor grinding after start because the pinion stayed engaged.

No noise or no response

If you get nothing, think electrical diagnosis. The ignition switch, starter relay, neutral safety switch, fuses, wiring harness, or the solenoid coil could be open. It could also be a dead starter motor.

Smoke or burning smell

Smoke from starter motor or a burning smell from starter signals overheating. That can come from cranking too long, a short circuit inside the motor, or a stuck engaged starter motor that never disengaged.

Intermittent starting problems

These usually come down to loose wiring, corrosion, failing brushes, a worn solenoid plunger, or a hot soak problem. Hot weather starter problems often stem from heat-soak expanding components which changes clearances and electrical resistance.

Troubleshooting Starter Motor Problems (Basic Diagnosis)

Before you pull the starter, perform a few quick checks. You’ll save time and money.

Check the battery

- Measure open-circuit voltage. Below about 12.4 V suggests a partial charge or worse.

- Load test the battery or crank the engine while watching voltage. If voltage sags significantly, the battery may be the real culprit. About 30–40% of “starter problems” are actually battery-related.

Inspect cables and connections

- Look for battery terminal corrosion. Clean both battery cables and the engine ground. High contact resistance causes voltage drop under load.

- Tug on the ground cable at the engine block. Loose ground points are a common root cause.

- Check fuses for starter motor control circuits and inspect the starter relay.

Listen to the sounds

- Single click with no crank: Solenoid engages but motor doesn’t. Think weak battery, bad contactor, or open motor.

- Rapid clicks: Battery voltage collapses. Recharge or replace the battery and retest.

- Grinding: Misalignment or gear damage.

- Silence: Ignition switch path, neutral safety switch, relay, or wiring.

Voltage drop test for starter

Use a multimeter. During cranking, measure voltage drop across the positive battery cable from the battery positive terminal to the starter B+ terminal. Do the same for the ground side from the starter housing to the battery negative. A voltage drop over a few tenths of a volt per side shows high resistance that needs attention.

Current draw test

Clamp an ammeter on the positive cable. Compare current draw to the vehicle spec if you have it. High current with slow cranking suggests a mechanical drag or a shorted motor. Low current with slow cranking suggests high resistance in the circuits.

Bench test starter motor

If you’ve removed the unit, you can bench test the starter motor. Secure it in a vise, apply battery power to B+, and trigger the solenoid. The pinion should kick out and the motor should spin strong. Safety first. Use eye protection and heavy cables. Keep hands clear of the pinion.

Simple test for solenoid

Briefly bridging the B+ and S terminals can test the solenoid actuation in some designs. Do it with care. Use an insulated tool and only for a moment. This bypasses upstream switches so confirm the vehicle is in park or neutral with the parking brake engaged.

Starter Motor Maintenance and Lifespan

Typical lifespan

On average, you can expect 5–10 years or roughly 100,000–150,000 miles. Some units last the life of the vehicle. Others fail earlier under harsh conditions or frequent start-stop usage.

Common failure causes

- Worn brushes: The most common wear item. Brushes and the commutator take a beating under high current and stop-start duty.

- Solenoid failure: Contacts pit and the plunger can stick.

- Bendix drive failure: The pinion gear or the overrunning clutch can stick or slip.

- Internal shorts and insulation breakdown: Overheating and vibration take their toll.

- Contamination: Oil, dirt, and water ingress cause corrosion and electrical shorts.

Preventative measures

- Maintain the charging system. A weak alternator stresses the battery which hurts the starter. The voltage regulator and starter don’t talk directly yet the charging system impacts the starter’s life.

- Keep connections clean and tight. Battery terminal corrosion raises resistance and causes heat.

- Avoid excessive cranking. Use 10–15 second cranking intervals with cool-down periods to prevent overheating starter motor and damage to armature windings and field coils.

- Protect against contamination. Oil leaks near the starter invite failures. Water crossing can hit low-mounted starters with a splash that causes water damage starter motor over time.

Starter Motor Replacement: When & What to Expect

Repair vs. replace

You can rebuild a unit with brushes, bearings, a new solenoid contact set, and a rebuilt Bendix. That works for some fleets and service centers. Many shops replace the assembly because of labor time and warranty risk. Rebuilding starter motor kit options exist yet require skill. Starter motor repair vs replace becomes a cost and risk decision.

New vs. remanufactured vs. aftermarket

- New OEM: Highest cost but predictable quality. Typical part prices run from about $150 to $400+ depending on vehicle and brand.

- Remanufactured: Strong value for many applications. $80 to $250 is common. Choose a reputable rebuilder who replaces high-wear items and tests the unit.

- Aftermarket: Offers cost savings. Quality varies. Some aftermarket starter options exceed OEM performance while others miss the mark. Evaluate torque specs, current draw, and warranty.

- Brands: Bosch, Denso, Valeo, ACDelco, and Delco Remy supply a large slice of the market.

Labor and total cost

Labor time ranges widely from 1 to 4 hours. Some vehicles put the starter right up front. Others hide it under an intake manifold. Expect total replacement cost between $200 and $800+.

Professional installation vs. DIY

Pros do this quickly with proper safety precautions, a lift, and test equipment. DIY starter replacement is doable with basic tools on many vehicles. You’ll need a floor jack, stands, a socket set, torque specs, and the wiring diagram. Disconnect the battery first. Confirm routing and torque on battery cable connection to the starter and the ground. Double-check the neutral safety switch and relays if a no crank persists after installation.

Materials and Manufacturing for Design Teams: Laminations, Losses, and Processes

If you design or source starter motors, lamination material and the manufacturing route rank among your highest-impact choices. You want maximum torque per amp, minimum heat rise, and a stack that stays tight over millions of starts. Let’s walk through the core questions using the Problem–Explain–Guide–Empower framework.

Problem: You need to hit torque targets at low temperature with a small package and reasonable cost. You also need to survive high ambient under-hood heat and frequent duty cycles in start-stop applications. Your magnetic circuit must deliver peak power without wasting battery energy as heat.

Explain: Eddy currents and hysteresis dominate core loss in ferromagnetic materials. In a DC series motor, the magnetic field varies with commutation. That changing field drives eddy currents within the armature core. Laminations reduce those currents by breaking up the conductive path. Thinner laminations and higher interlaminar resistance cut eddy losses. Materials with low coercivity lower hysteresis loss. Together they reduce temperature rise and increase torque per amp.

Guide: Material considerations vs. manufacturing processes.

Material considerations

- Non-oriented silicon steel (CRNGO): The workhorse for rotating machines. Balanced magnetic properties in all directions. Common thicknesses include 0.5 mm, 0.35 mm, and thinner grades for high-frequency or high-efficiency motors. Starters typically favor mid-range thickness for mechanical robustness and cost.

- Grain-oriented silicon steel (CRGO): Optimized for a single direction of flux and used mainly in transformers. It rarely makes sense in a rotating armature.

- Cobalt-alloy steels: High saturation flux density and good at elevated temperatures. High cost limits use in mainstream starters. You may consider them in aerospace, racing, or extreme power density cases.

- Permanent magnet material choice: If you choose a permanent magnet starter design, magnet grade and temperature rating become critical. Keep magnet demagnetization at bay under hot soak conditions and during current spikes.

Manufacturing and assembly processes

- Stamping: The standard for high volume. It balances accuracy, speed, and cost. Control burr height and direction to protect insulation.

- Laser cutting: Great for prototyping and low volume. Minimal tooling cost. Heat affected zones can increase core loss unless you anneal or specify proper cutting parameters.

- Waterjet or wire EDM: Precise with little thermal impact. Slower and not usually viable for mass production.

- Stack assembly: Interlocking features press together like a LEGO style fit which gives rigidity without welding. Bonding with adhesive offers low-loss stacks with excellent rigidity. Riveting and cleating work yet can slightly disturb local magnetic paths. Welding should be used carefully because heat can harm magnetic properties.

- Insulation and coatings: Choose a coating class that survives your forming and stacking process. Good interlaminar resistance matters for current draw and heat. Confirm compatibility with adhesives if you choose bonding.

Empower: Don’t over-optimize a single parameter. Start with a system model that ties torque, current draw, temperature rise, and mechanical envelope to material spec and lamination thickness. Then tune your process to hit those targets with realistic tolerances and assembly variation. If your team needs a starting point, non-oriented silicon steel around 0.35–0.5 mm with a robust bonding or interlock stack is a proven baseline for automotive starters.

Which Application Is This For? Matching Design Choices to Use Cases

Heavy-duty diesel engines

- Problem: High compression demands high torque at the pinion.

- Guide: Gear reduction starter with a larger planetary gear train. High current allowances in cabling and battery. Consider thicker laminations for mechanical strength but confirm the eddy current penalty is acceptable since temperature can spike under repeated cranks.

- Watchouts: Ensure the overrunning clutch is rated for torque spikes. Validate pinion gear hardness against the flywheel ring gear.

Passenger cars with start-stop systems

- Problem: Frequent cycling and hot soak.

- Guide: Permanent magnet gear reduction starters offer compact size and efficiency. Specify lamination coatings and adhesives that handle repeated thermal cycling. Validate brushes and commutator life under high cycle counts. Consider improved ventilation or heat sinking in the starter housing design.

- Watchouts: Magnet demagnetization at temperature. Hot weather starter problems increase if material ratings are marginal.

Cold climate markets

- Problem: Oil viscosity rises and the engine cranks hard. Battery capacity falls in the cold.

- Guide: Confirm cranking amps requirement with a margin. Reduce circuit resistance with larger battery cables and short ground paths. Select a lamination thickness and grade that minimizes loss because every amp counts in the cold.

- Watchouts: Freezing weather starter issues can reveal marginal brushes and weak solenoids.

Tight packaging in transverse powertrains

- Problem: Space constraints near the transmission and subframe.

- Guide: Gear reduction starter with permanent magnets and a compact planetary set. Use FEM to optimize flux paths in the laminated armature. Interlock stacks reduce axial length without adding bonding equipment.

- Watchouts: Ensure access for service. Avoid sharp heat gradients from exhaust proximity.

Prototyping vs. high-volume production

- Prototyping: Laser cut laminations give you speed and design freedom. You can iterate slot geometry for the armature quickly. Expect slightly higher core loss unless you manage the HAZ.

- High volume: Stamping dies pay off with cost and consistency. Bonding or interlocking reduces noise and vibration and improves reliability in the field.

Frequently Asked Engineering and Service Questions

- How car starter works in plain terms: The ignition switch energizes a relay and the solenoid. The solenoid pushes the pinion into the flywheel and closes a high-current contact. The motor spins and cranks the engine. The overrunning clutch saves the motor once the engine fires.

- Starter motor vs solenoid: The solenoid is the control and engagement device. The motor generates torque.

- What causes starter to fail: Worn brushes, solenoid contact wear, Bendix drive issues, internal shorts, contamination, and overheating.

- Can a bad battery mimic bad starter: Yes. Low voltage under load produces slow cranking or clicking with no crank.

- Voltage drop test starter: Measure voltage loss on the positive and ground sides during cranking. High drop points you to bad connections or damaged cables.

- Bench test starter motor: Secure the unit, energize the solenoid, and verify strong spin and proper pinion throw.

- Direct drive starter motor vs gear reduction starter: Direct drive is simpler but larger. Gear reduction is more compact and efficient with better torque density.

- Permanent magnet starter vs field coil starter: PM starters are efficient and compact. Field-coil designs handle heat and abuse well in some heavy-duty contexts.

- Flywheel ring gear damage: Causes grinding and intermittent no crank. Inspect both the pinion gear and the flywheel during service.

- Intermittent starting problems: Often wiring, relays in the starting circuit, or a neutral safety switch out of adjustment. Sometimes brushes or a solenoid plunger hang up when hot.

- Electrical shorts starter: Visible as high current draw, smoke from starter motor, or a burning smell from starter. Stop cranking and diagnose.

You’ll also hear questions about ignition timing and starter. If ignition timing is severely advanced during cranking, kickback can occur which hammers the pinion and overrunning clutch. Keep timing within spec. You may get engine cranks but won’t fire complaints which point beyond the starter to spark plugs, the fuel pump, or a sensor issue.

The Business Side: Specifications, Costs, and Sourcing

- Starter motor specifications to track: Nominal torque at the pinion, free run current, stall current, RPM for engine starting, and mass. Include thermal rise over a defined duty cycle and any duty cycle limits.

- Current draw starter motor: Validate against battery capability and cable sizing. Use real cold-crank tests where possible.

- Average labor cost starter replacement: Expect one to four hours of labor based on access and platform. That translates to roughly $100–$400+ in labor for most regions.

- Parts decisions: Genuine vs aftermarket parts is a risk-reward trade. Remanufactured vs new starter is a cost and warranty decision. Choose suppliers with clear test protocols.

- Professional starter replacement vs DIY starter replacement: Factor in lift access, safety, and the ability to perform voltage drop tests and a bench test starter motor before returning the vehicle to service.

A Short Primer on Electrical Theory That Matters Here

You don’t need a deep dive into electromagnetic theory to make better choices. A few key ideas help.

- Magnetic permeability: Think of it as how easily a material allows magnetic field lines to pass through it. Like how a sponge soaks up water. Higher permeability reduces magnetizing current and improves torque.

- Hysteresis loss: Energy lost each cycle as the magnetic domains flip. Materials with low coercivity reduce it. In a commutated DC motor, local fields change as commutator segments switch so hysteresis still matters.

- Eddy current loss: Those are the little whirlpools of current induced in the core. Laminations with good insulation break up the whirlpools and cut heating.

- Resistance in starter circuit: Even small resistance at high current creates big voltage drops. That’s why clean, tight connections matter.

If you want standards and references to ground your choices, look to ASTM A677 for non-oriented electrical steel specifications and IEC/IEEE testing practices for core loss characterization. You can also consult SAE and OEM-specific standards for starter performance and durability validation.

Conclusion: The Unsung Hero of Your Car’s Start

The starter motor rarely gets the spotlight. It sits low on the engine and just gets the job done. Yet it ties together high current electrical design, precision mechanics, and magnetic circuits that live or die by lamination choices. Get the laminations right and you unlock higher torque per amp, lower heat, and longer service life. Get the system details right and you avoid costly no crank no start comebacks.

Your Engineering Takeaway

- Define the problem first: torque at the pinion, duty cycle, ambient temperature, packaging, and cost.

- Use laminations wisely: choose silicon steel grades with proper thickness and coatings to reduce eddy currents and hysteresis without sacrificing strength.

- Pick the right architecture: direct drive for simplicity or gear reduction with planetary gears for torque density. Permanent magnet starters cut size and current but demand careful heat and magnet selection.

- Validate the electrical path: low resistance connections, correct cable sizing, robust relays in the starting circuit, and a healthy battery and charging system.

- Diagnose with data: use voltage drop tests, current draw tests, and a clean bench test for the starter motor before replacement.

- Source with confidence: weigh new, remanufactured, and aftermarket options based on specs, warranty, and test practices.

If you’re evaluating materials, stack processes, or complete assemblies for new designs or supplier transitions, set up a focused technical review. Bring your torque targets, duty cycles, and packaging constraints. A short working session with your lamination and starter partners will save you weeks of iteration and will keep the engine roaring when it matters.

—

Sources and further reading: IEC and IEEE publications on rotating electrical machine losses, ASTM A677 for non-oriented electrical steel, SAE standards and OEM test protocols for starting system performance.