What is a Permanent Magnet? Understanding Their Science, Types, and Everyday Uses

Every engineer, product designer, and procurement manager has encountered them. From the simple refrigerator magnet holding up a child’s drawing to the high-performance heart of an electric vehicle’s motor, permanent magnets are one of the most pervasive and vital components in modern technology. If you’ve ever found yourself weighing the trade-offs between different magnetic materials or simply wondered what gives these objects their persistent, invisible force, you’re in the right place.

A permanent magnet is a material that creates its own persistent magnetic field without needing an external power source. Unlike an electromagnet, which requires a constant flow of electricity to function, a permanent magnet’s power comes from its intrinsic atomic structure. Understanding this fundamental difference is the first step toward appreciating their indispensable role in everything from tiny sensors to massive industrial machinery.

What We’ll Cover

- How Do Permanent Magnets Work? A look at the science behind their enduring attraction, from electron spins to magnetic domains.

- Types of Permanent Magnets: A guide to the spectrum of materials, from cost-effective ferrites to powerful rare earth magnets.

- Applications of Permanent Magnets: Discovering where these components are used across countless industries.

- Permanent vs. Electromagnets: A clear breakdown of the key differences and when to use each.

- Factors Affecting Performance: Understanding the real-world conditions that impact a magnet’s longevity and strength.

How Do Permanent Magnets Work? The Science Behind the Enduring Attraction

The seemingly magical force of a permanent magnet isn’t magic at all; it’s a fascinating dance of physics happening at the atomic level. To truly grasp how they work, we need to zoom in on the material’s fundamental building blocks.

The Atomic Origin of Magnetism

Every atom contains electrons, and these tiny particles are the source of magnetism. Two specific actions of electrons create a small magnetic field, known as a magnetic moment:

In most materials, these tiny magnetic moments are completely random. For every electron spinning one way, there’s another spinning the opposite way, and their magnetic fields cancel each other out. This is why you can’t stick a piece of wood or plastic to your fridge. However, in certain materials—specifically ferromagnetic materials like iron, nickel, and cobalt—things are different. These elements have unpaired electrons whose spins can be aligned, creating a net magnetic moment.

Magnetic Domains: The Power of Teamwork

Even in a block of iron, the atomic magnets don’t automatically align. Instead, they group themselves into microscopic regions called magnetic domains. Within each domain, all the atomic magnetic moments are pointing in the same direction, like a tiny, perfectly organized army. But the block as a whole isn’t a magnet yet because each domain is pointing in a random direction, canceling out its neighbors. The material is strong, but its strength is disorganized.

This is where the magnetization process comes in. By exposing the ferromagnetic material to a very strong external magnetic field (often from a powerful electromagnet), we provide the energy needed to force these domains to align. They pivot and merge until a vast majority of them are pointing in the same direction.

For a material to become a permanent magnet, it must be a “hard” magnetic material. This means that once its domains are aligned, they are stubborn and resist falling back into their random, disordered state after the external field is removed. This locked-in alignment is what creates the persistent, powerful external magnetic field we can observe and use.

Key Properties of Permanent Magnets

When engineers select a magnet, they look at several key metrics that define its performance. Think of these as the magnet’s technical specifications.

- Remanence (Br): This value tells you how much magnetic flux density remains in the material after the external magnetizing field is removed. In simple terms, it’s a measure of the magnet’s raw strength. It’s typically measured in units of Tesla (T) or Gauss (G).

- Coercivity (Hcj/Hcb): This is the material’s inherent resistance to being demagnetized by an external opposing magnetic field. A high coercivity is crucial for magnets used in environments with fluctuating magnetic fields or high temperatures, such as in an electric motor. It’s like the magnet’s stubbornness.

- Energy Product (BHmax): Often considered the primary indicator of a magnet’s overall power, the maximum energy product represents the total magnetic energy stored within the magnet. Measured in MegaGaussOersteds (MGOe), a higher BHmax means you can achieve more magnetic force with a smaller volume of material, which is critical for miniaturization in electronics and high-power-density motors.

Types of Permanent Magnets: A Spectrum of Strength, Temperature, and Cost

Not all permanent magnets are created equal. They are a diverse family of materials, each with a unique profile of strength, cost, and environmental resistance. Choosing the right one is a critical design decision based on the specific application’s demands.

Rare Earth Magnets (The Powerhouses)

As the name suggests, these magnets are made from rare earth elements on the periodic table. They are, by far, the strongest class of permanent magnets available today.

Neodymium (NdFeB)

- Properties: Neodymium magnets are the undisputed champions of magnetic strength, boasting the highest BHmax of any commercially available magnet. They offer an incredible amount of magnetic force in a very small package.

- Applications: Their strength-to-size ratio makes them indispensable in modern technology. You’ll find them in high-performance motor core laminations, electric vehicle (EV) traction motors, hard disk drives, high-end speakers and headphones, and the powerful magnets used in MRI machines.

- Considerations: Their main drawbacks are a relatively low maximum operating temperature and poor corrosion resistance. They are very brittle and almost always require a protective coating (like nickel-copper-nickel) to prevent them from rusting and crumbling.

Samarium Cobalt (SmCo)

- Properties: The predecessor to Neodymium magnets, Samarium Cobalt is the second-strongest type of magnet. Its key advantages are superior temperature stability—it can operate at much higher temperatures than NdFeB—and excellent corrosion resistance without needing a coating.

- Applications: These traits make SmCo the go-to choice for demanding applications in aerospace, military equipment, high-temperature motors and sensors, and medical implants where reliability is non-negotiable.

- Considerations: SmCo magnets are more expensive and more brittle than Neodymium magnets, which reserves them for applications where their specific benefits justify the cost.

Metallic Alloy Magnets

Alnico

- Properties: Made from an alloy of aluminum, nickel, and cobalt (Al-Ni-Co), Alnico magnets offer excellent temperature stability, able to function at up to 550°C (1022°F), and have high residual induction.

- Applications: Before the advent of rare earth magnets, Alnico was the strongest material available. Today, it remains relevant in high-temperature applications like automotive sensors, ABS systems, meters, and famously, in electric guitar pickups for its unique tonal qualities.

- Considerations: Alnico has a relatively low coercivity, meaning it can be more easily demagnetized by external fields compared to rare earth or ceramic magnets.

Ceramic (Ferrite) Magnets (The Workhorses)

- Properties: Composed of strontium ferrite or barium ferrite, these are the most common and cost-effective permanent magnets. They offer moderate magnetic strength but have outstanding corrosion resistance and can operate at reasonably high temperatures.

- Applications: Their low cost and reliability have made them ubiquitous. They are the driving force in most loudspeakers, small DC motors, magnetic separators in recycling plants, and, of course, the classic refrigerator magnet.

- Considerations: Ferrite magnets are hard and brittle (like a ceramic pot) and have a lower energy product than metallic magnets, meaning they are larger and heavier for the same magnetic output.

Flexible Magnets

- Properties: These aren’t a distinct chemical type but rather a composite. They are made by mixing ferrite magnetic powder with a flexible polymer binder, like rubber or vinyl. They have low magnetic strength but can be easily cut, bent, and shaped.

- Applications: Their flexibility is their main selling point. You’ll find them used in refrigerator door seals, magnetic signs for vehicles, crafts, and educational toys.

| Feature / Magnet Type | Neodymium (NdFeB) | Samarium Cobalt (SmCo) | Alnico | Ferrite (Ceramic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Strength (BHmax) | 35-52 MGOe | 16-32 MGOe | 1.5-10 MGOe | 1.0-4.5 MGOe |

| Max. Operating Temp. | 80°C to 230°C | 250°C to 350°C | 450°C to 550°C | 250°C to 300°C |

| Cost (Relative) | High (Volatile) | Very High | Medium-High | Low |

| Corrosion Resistance | Poor (Requires Coating) | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent |

Applications of Permanent Magnets: Everywhere You Look

Once you start looking for them, you’ll find permanent magnets are a hidden pillar of our daily lives and industrial infrastructure. The global market for these components was estimated at around USD 25 Billion in 2023 and is projected to grow at a CAGR of over 7%, driven largely by the transition to electric mobility and renewable energy.

- Everyday Life: The most obvious examples are refrigerator magnets, compass needles, cabinet latches, and magnetic toys. They are also in the magnetic strips on credit cards and ID badges.

- Electronics: They are essential for converting electrical energy into sound in speakers and headphones. The tiny motors that create vibrations in your phone and power drones and computer fans rely on permanent magnets. Hard disk drives use powerful NdFeB magnets to control the read/write head with incredible precision.

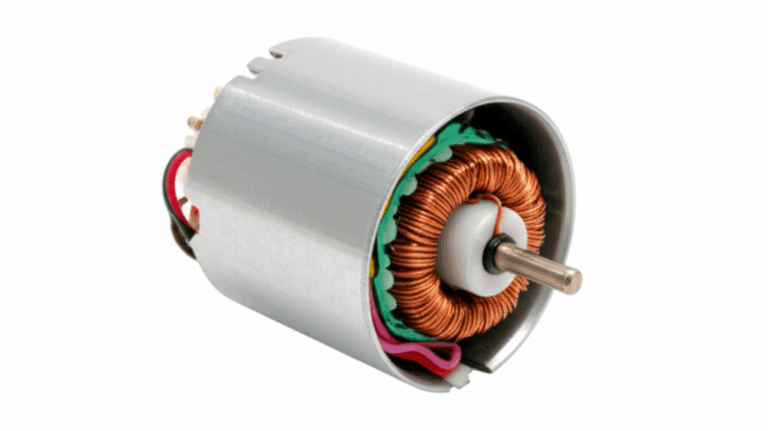

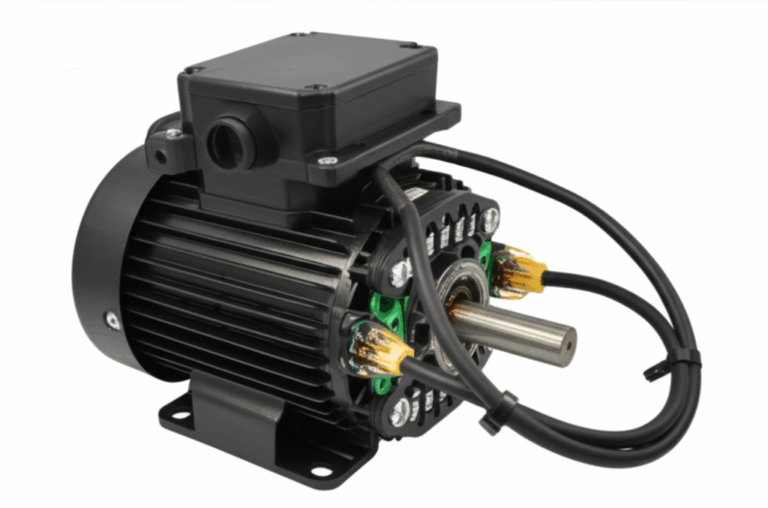

- Automotive: A modern car contains dozens of magnets. They are used in everything from starter motors and ABS sensors to power window lifters. The shift to electric vehicles has created a massive demand; a typical EV traction motor can use 2-3 kg of Neodymium magnets to efficiently convert battery power into motion.

- Industrial: Magnets perform heavy lifting in industrial settings. Magnetic separators pull ferrous metals from waste streams in recycling facilities, powerful lifting magnets move scrap metal, and magnetic chucks hold steel workpieces in place for machining. The fundamental motor principle relies on the interaction between permanent magnets and electromagnets.

- Medical: The medical field relies heavily on magnets. The most prominent example is Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), which uses an incredibly powerful superconducting magnet to generate detailed images of the human body. They are also used in pacemakers, drug delivery systems, and surgical tools.

- Renewable Energy: Permanent magnet generators are at the heart of many modern wind turbines. Direct-drive turbines, especially those used in offshore wind farms, can contain tons of rare earth magnets to generate electricity efficiently without a gearbox.

Permanent vs. Electromagnets: Understanding the Key Differences

It’s crucial to distinguish permanent magnets from their powered counterparts, electromagnets. While both produce a magnetic field, they operate on different principles and are suited for different tasks.

- Nature of the Field: A permanent magnet has a constant, “always on” magnetic field. An electromagnet’s field only exists when an electric current flows through its coil, and disappears the moment the power is cut.

- Power Requirement: Permanent magnets require no external power to maintain their field. Electromagnets require a continuous supply of electricity.

- Strength Control: The strength of a permanent magnet is fixed based on its material and geometry. An electromagnet’s strength is highly controllable and can be varied by changing the electric current.

- Applications:

- Permanent magnets are preferred where a constant, reliable field is needed without a power source. This includes most electric motors where the interaction between the permanent magnets on the rotor and the electromagnets on the stator creates motion. Understanding the relationship between the stator and rotor is key to motor design.

- Electromagnets are preferred where control is paramount. Think of industrial lifting cranes that need to pick up and then release scrap metal, or the powerful magnets used in particle accelerators.

Factors Affecting Permanent Magnet Performance and Longevity

A permanent magnet isn’t necessarily permanent forever. Several environmental factors can degrade its performance or even demagnetize it completely. For engineers, anticipating these factors is critical for long-term product reliability.

- Temperature: This is arguably the biggest enemy of a magnet. Every magnetic material has a Curie Temperature, a critical threshold at which it loses all its magnetic properties. Well below this point, high temperatures will still cause a temporary (reversible) loss of strength. However, if a magnet is heated above its maximum operating temperature, it can suffer permanent (irreversible) losses, meaning it won’t regain its full strength upon cooling.

- External Demagnetizing Fields: Exposing a magnet to a strong magnetic field from another magnet or an electromagnet in the opposite orientation can weaken its internal domain alignment, reducing its strength. This is why high coercivity is such an important property.

- Physical Shock and Vibration: For brittle materials like Ferrite and Neodymium, severe physical impacts can sometimes provide enough energy to knock some of the magnetic domains out of alignment, causing a slight reduction in performance.

- Corrosion: As mentioned, this is the Achilles’ heel of Neodymium magnets. Exposure to moisture and oxygen will cause them to rapidly corrode into a useless powder. This is why protective coatings of nickel, zinc, or epoxy are standard for almost all NdFeB applications. Materials like electrical steel laminations, used in electromagnets, also require careful material selection and coatings to manage performance and longevity.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power and Innovation of Permanent Magnets

From the simple compass that guided early explorers to the complex motors powering our sustainable future, permanent magnets are a foundational technology. They are the silent, unseen workhorses that translate the principles of physics into tangible motion, sound, and data storage.

Their power lies in their ability to store energy in the form of a persistent magnetic field, a property derived from the quantum mechanical behavior of electrons. By understanding the core characteristics of different magnetic materials—from the sheer power of Neodymium to the cost-effective reliability of Ferrite—engineers can make informed decisions that optimize performance, cost, and longevity.

As research continues into new materials that reduce reliance on critical rare earth elements and push the boundaries of temperature resistance and strength, the role of permanent magnets will only continue to expand. They are a testament to how mastering the properties of materials at the atomic level can unlock innovations that change the world.