What is a Squirrel Cage Motor? Understanding its Design, Function, and Widespread Applications

As a design engineer or procurement manager, you face a constant balancing act. You need to specify components that deliver maximum performance and reliability without blowing up the budget. When it comes to electric motors, one name surfaces more than any other: the squirrel cage motor. You’ve likely heard it called the “workhorse of industry,” a title it has earned over a century of dependable service.

But what exactly is a squirrel cage motor? Why does this specific design dominate an estimated 85-90% of all industrial applications? If you find yourself weighing the trade-offs of different motor types and want to understand the fundamental principles behind this ubiquitous technology, you’re in the right place. This guide will break down the engineering behind the squirrel cage motor, explaining not just what it is, but why it works so well, where it excels, and what limitations you need to consider for your next project.

In This Article

- The Core Principle: How a Squirrel Cage Motor Works

- Key Components and Construction

- Types of Squirrel Cage Motors

- The Undeniable Advantages

- Disadvantages and Design Considerations

- Where You’ll Find Them: Common Applications

- A Quick Comparison: Squirrel Cage vs. Wound Rotor Motors

- Your Engineering Takeaway: Why This Motor Still Dominates

The Core Principle: How a Squirrel Cage Motor Works

At its heart, the squirrel cage motor is a type of AC induction motor. Its magic lies in a brilliant and simple application of physics—no direct electrical connections to the rotating part are needed. It all boils down to a principle called electromagnetic induction.

Electromagnetic Induction at Play

Let’s start with a basic concept first described by Michael Faraday. If you move a magnet past an electrical conductor (like a copper wire), you generate a current in that wire. It’s a fundamental law of physics. The reverse is also true: if you pass a current through a wire, it creates a magnetic field around it. An induction motor cleverly uses both of these principles to create motion from electricity.

The Rotating Magnetic Field (RMF)

The process begins in the stationary part of the motor, the stator. When you connect a three-phase AC power supply to the stator’s windings, something incredible happens. Because the current in each of the three phases peaks at a slightly different time, their combined magnetic fields create a single, larger magnetic field that rotates at a constant speed.

Think of it like three people standing around a playground merry-go-round. If they push on it one after the other in a perfectly timed sequence, they can make it spin smoothly without ever having to run around it themselves. The stator windings do the same thing with magnetic forces, creating an invisible, rotating magnetic field (RMF). The speed of this field is known as the synchronous speed.

Rotor Current and Torque Generation

Now, let’s look at the rotor—the “squirrel cage” itself. It’s essentially a set of conductive bars shorted out at both ends by rings. As the stator’s RMF sweeps across these stationary rotor bars, it’s like moving a powerful magnet past a conductor. True to Faraday’s Law, this induces a massive electrical current in the rotor bars.

Because these bars are short-circuited by the end rings, this current flows freely, creating its own powerful magnetic field around the rotor. And here’s the brilliant part, governed by Lenz’s Law: the rotor’s newly created magnetic field will always arrange itself to oppose the change that created it. In practical terms, this means it gets “dragged” along by the stator’s RMF. This dragging force is what we call torque, and it’s what makes the motor’s shaft spin and do useful work.

Understanding “Slip”

Here’s a crucial concept: for an induction motor to produce torque, the rotor must always turn slightly slower than the rotating magnetic field. This difference in speed is called slip.

Why is slip necessary? Imagine the rotor somehow managed to catch up and spin at the exact same synchronous speed as the RMF. At that point, from the rotor’s perspective, the magnetic field would no longer be “sweeping” past its bars—it would be stationary. With no relative motion between the field and the bars, no current would be induced, no rotor magnetic field would be created, and therefore, no torque would be produced. The rotor would start to slow down.

As soon as it slows, slip is re-established, current is induced again, and torque is produced. This self-regulating nature means the rotor is in a constant state of “chasing” the RMF but never quite catching it. The amount of slip depends on the load; a heavily loaded motor will have more slip (a larger speed difference) than one with no load.

Key Components and Construction

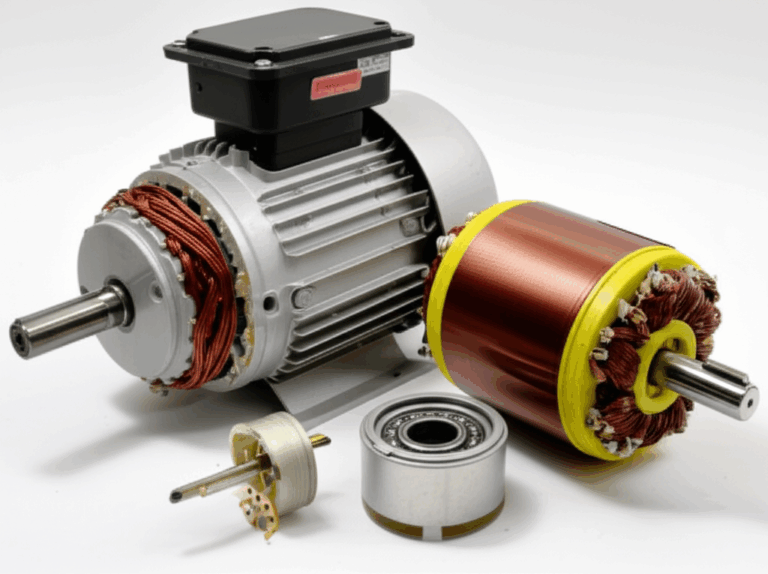

The beauty of the squirrel cage motor lies in its elegant simplicity. While other motor designs rely on brushes, commutators, or permanent magnets, this design has very few moving parts that can wear out, making it exceptionally reliable. The two main functional parts are the stator and rotor, each a marvel of engineering.

The Stator: The Stationary Part

The stator is the motor’s stationary outer housing. It consists of two primary elements:

The Rotor: The “Squirrel Cage” Itself

The rotor is the rotating component that transfers mechanical power to the load via the motor shaft. Its construction is where the motor gets its unique name.

- Rotor Core: Like the stator, the rotor core is made from a stack of thin laminations to reduce energy losses. The quality of the rotor core lamination is vital for efficiency.

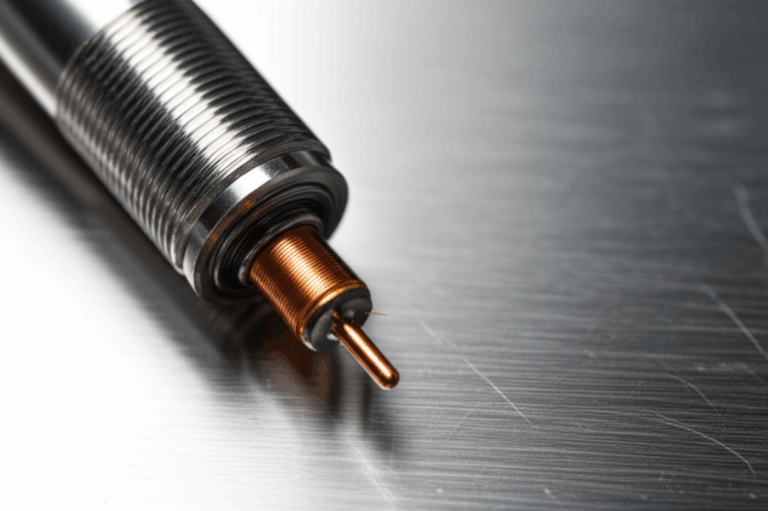

- Rotor Bars: Running through slots in the rotor core are conductive bars, typically made of aluminum or copper. In most motors, molten aluminum is die-cast directly into the rotor slots, forming the bars and end rings in one solid piece. Copper bars offer higher conductivity and efficiency but are more expensive and complex to manufacture.

- End Rings: These conductive rings are located at each end of the rotor core and are integrally connected to the rotor bars. Their job is to create a complete, short-circuited path for the induced currents to flow.

When you look at the rotor assembly without the laminated core, the bars and end rings form a cylindrical cage-like structure—remarkably similar to the exercise wheels used for pet rodents. Hence, the name “squirrel cage motor.”

Air Gap

The tiny, precisely controlled space between the outer surface of the rotor and the inner surface of the stator is called the air gap. This gap is a critical design parameter. It must be as small as mechanically possible to ensure strong magnetic coupling between the stator and rotor, which maximizes efficiency. However, it must also be large enough to prevent any physical contact due to thermal expansion or bearing wear.

Bearings and Housing

These supporting components are crucial for a long operational life. Bearings, typically ball or roller types, support the rotor and allow it to spin freely with minimal friction. In fact, reliability studies show that bearing failures account for up to 40% of all motor failures, highlighting the importance of proper lubrication and maintenance. The motor housing, or enclosure, protects all these internal components from dust, moisture, and mechanical damage.

Types of Squirrel Cage Motors

While the operating principle is the same, squirrel cage motors come in two main electrical configurations designed for different power supplies.

Single-Phase Squirrel Cage Motors

These are the motors you’ll find all around your home in appliances like washing machines, dryers, refrigerators, and fans. A single-phase AC supply can’t create a true rotating magnetic field on its own; it just creates a pulsating one. To solve this, single-phase motors require an extra starting mechanism—often a separate “start winding” used in conjunction with a capacitor—to create an initial rotational “push” and get the rotor moving in the right direction. Once running, this starting circuit is typically disengaged.

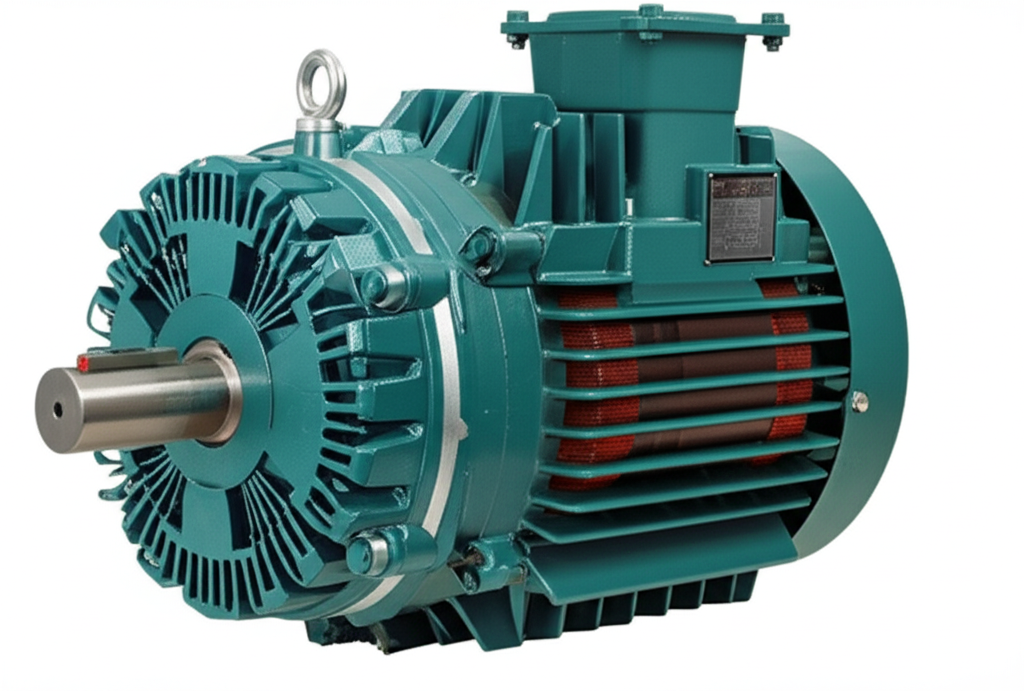

Three-Phase Squirrel Cage Motors

This is the true industrial powerhouse. As we discussed, a three-phase power supply naturally creates a smooth, rotating magnetic field in the stator, making the motor inherently self-starting. They are more efficient, have a better power factor, and can be built to much higher horsepower ratings than their single-phase counterparts. You’ll find them running nearly everything in factories, processing plants, and commercial buildings.

The Undeniable Advantages

There’s a reason this design is so dominant. For engineers and procurement managers, the benefits directly address core business needs: reliability, cost, and performance.

Robustness and Durability

The squirrel cage rotor is a solid, almost indestructible block of metal with no electrical connections. There are no brushes to wear down, no commutators to arc, and no slip rings to maintain. This elegantly simple, brushless design leads to incredible durability. With proper maintenance, a typical industrial squirrel cage motor can operate reliably for 15 to 30 years or more.

Simplicity and Low Maintenance

Fewer parts mean fewer points of failure. The maintenance schedule for a squirrel cage motor is wonderfully straightforward, primarily consisting of bearing lubrication (annually or every 2,000-4,000 operating hours) and keeping the motor clean. This minimal requirement reduces downtime and lowers the total cost of ownership.

Cost-Effectiveness

The simple design and materials make squirrel cage motors relatively inexpensive to manufacture. Analysis shows that their initial purchase cost is typically 20-40% lower than comparable-power permanent magnet or DC motors. This economic advantage makes them the go-to choice for a vast range of applications where exotic performance isn’t required.

High Efficiency (Modern Designs)

While older motors could be inefficient, modern designs are a different story. Thanks to global efficiency standards like NEMA (in North America) and IEC (internationally), manufacturers have made huge strides. Premium Efficiency (IE3) motors routinely achieve efficiencies of 90-94%, while Super Premium (IE4) models can reach 95-96%. This translates directly into lower electricity bills and a smaller carbon footprint over the motor’s lifespan. The quality of the motor core laminations is a primary driver of these efficiency gains.

Disadvantages and Design Considerations

No single technology is perfect for every job. Being an effective engineering partner means being honest about a product’s limitations. Here are the key considerations when specifying a squirrel cage motor.

High Starting Current (Inrush Current)

When first switched on, a squirrel cage motor draws a very large amount of current from the power supply—typically 5 to 7 times its rated full-load current. This is because at standstill (100% slip), the motor behaves like a transformer with a shorted secondary coil. This inrush current can cause voltage dips in the electrical system, affecting other equipment. To manage this, various starting methods are employed:

- Direct-On-Line (DOL) Starting: The simplest method, used for smaller motors where the inrush current is manageable.

- Star-Delta Starting: Reduces the starting current to about one-third of the DOL value.

- Soft Starters: Electronic devices that gradually ramp up the voltage to provide a smooth, controlled start.

Fixed Speed Operation (without VFD)

The running speed of a standard squirrel cage motor is inherently tied to the frequency of the AC power supply and the number of poles in its stator winding. This makes it a fixed-speed device, which is perfectly fine for applications like pumps or fans that just need to run continuously. However, for applications requiring speed control, you need a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD). A VFD is an electronic controller that can adjust the frequency of the power supplied to the motor, allowing for precise speed regulation.

Lower Starting Torque (compared to wound rotor)

While generally providing good starting torque for most applications, a standard squirrel cage motor’s starting torque is lower than that of a DC motor or a wound rotor induction motor. For very high-inertia loads that require a massive initial breakaway force, a different motor type or a specially designed high-torque squirrel cage motor might be necessary.

Where You’ll Find Them: Common Applications

The combination of reliability, low cost, and solid performance has made the squirrel cage motor ubiquitous. Their impact is so vast that electric motors, predominantly squirrel cage types, consume an estimated 45-50% of the world’s total electricity. You will find them everywhere:

- Industrial Machinery: They are the prime mover for over 75% of industrial pumps, fans, compressors, and blowers.

- Manufacturing and Conveyor Systems: From large conveyor belts in distribution centers to the machine tools on a factory floor, these motors keep production lines moving.

- HVAC Systems: Every large commercial air conditioning and ventilation system relies on squirrel cage motors to move air and circulate fluids.

- Consumer Appliances: As mentioned, they power countless devices in our homes.

- Electric Vehicles (Certain Types): While many modern EVs use permanent magnet motors, some, notably certain models from Tesla, have successfully utilized high-performance AC induction motors for their robustness and lack of rare-earth magnets.

A Quick Comparison: Squirrel Cage vs. Wound Rotor Motors

A common point of comparison is with the wound rotor induction motor, which is the other main type of induction motor. The key difference lies entirely in the rotor construction.

| Feature | Squirrel Cage Motor | Wound Rotor Motor |

|---|---|---|

| Rotor | Solid conductive bars short-circuited by end rings | Insulated windings connected to external slip rings |

| Complexity | Very Simple | More Complex (windings, brushes, slip rings) |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Maintenance | Very Low | Higher (brush and slip ring inspection/replacement) |

| Starting Torque | Good | Very High (adjustable via external resistors) |

| Speed Control | Requires a VFD | Limited speed control possible via rotor resistance |

Essentially, the wound rotor motor sacrifices simplicity and cost for the ability to achieve extremely high starting torque and some degree of speed control without a VFD. For the vast majority of applications, however, the squirrel cage motor’s balance of features is far more practical.

Your Engineering Takeaway: Why This Motor Still Dominates

The squirrel cage motor isn’t just a legacy technology; it’s a foundational pillar of modern industry that continues to evolve. Its enduring dominance comes from a near-perfect balance of essential engineering virtues: it is simple, reliable, efficient, and cost-effective. While more specialized motors exist for niche applications, no other design offers such a compelling all-around package for the majority of industrial and commercial needs.

When you specify a modern, high-efficiency squirrel cage motor, you are choosing a proven, dependable solution that minimizes operational headaches and delivers excellent long-term value.

Key Takeaways for Your Next Project:

- Simplicity is Strength: The lack of brushes and internal electrical connections makes it incredibly robust and low-maintenance.

- Efficiency is Key: Modern IE3 and IE4 motors offer significant energy savings over their operational lifespan.

- Starting Current Must Be Managed: Always consider the impact of inrush current on your electrical system and select an appropriate starting method (DOL, Star-Delta, Soft Starter).

- Pair with a VFD for Speed Control: For variable-load applications like pumps and fans, pairing a squirrel cage motor with a VFD is the industry standard for maximizing efficiency and control.

Understanding these core principles empowers you to have more productive conversations with suppliers and make design and purchasing decisions with confidence, ensuring you select the right motor for the job every time.

Related FAQs

Why is it called a squirrel cage motor?

It’s named for its rotor. If you were to remove the laminated steel core, the embedded aluminum or copper bars connected by end rings would look just like a cylindrical cage or exercise wheel for a small animal like a squirrel.

Are squirrel cage motors AC or DC?

Squirrel cage motors are a type of AC (Alternating Current) motor. Their operation relies entirely on the rotating magnetic field created by an AC power supply. They cannot run on DC power directly.

What is the difference between an induction motor and a squirrel cage motor?

This can be a point of confusion. “Induction motor” is the broad category of motor that works on the principle of electromagnetic induction. The “squirrel cage motor” is the most common type of induction motor, characterized by its unique rotor design. The other, less common type is the wound rotor motor. So, all squirrel cage motors are induction motors, but not all induction motors are squirrel cage motors.

What are the limitations of a squirrel cage induction motor?

The main limitations are its high starting current, which can stress electrical systems; its inherently fixed speed, which requires a VFD for adjustment; and its lower starting torque compared to DC or wound rotor motors.

What are the starting methods for a squirrel cage motor?

The most common methods include Direct-On-Line (DOL) for small motors, Star-Delta starters to reduce starting current, soft starters for smooth electronic voltage ramping, and Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs), which provide the most control over both starting and running speed.