What is an Eddy Current Brake? A Guide to Contactless Braking Technology

Every engineer who designs a system with moving parts eventually faces the same critical challenge: how to slow it down or stop it reliably, efficiently, and with minimal wear. For decades, the answer has been friction. But if you’ve ever found yourself designing around the limitations of friction brakes—the constant maintenance, the brake dust, the noise, the potential for fade at high temperatures—you know there has to be a better way for certain applications. You’re in the right place.

This article explores a powerful alternative: the eddy current brake. It’s a fascinating piece of engineering that uses the magic of electromagnetism to create a smooth, silent, and virtually wear-free braking force. We’ll dive into the core principles, weigh the pros and cons, and explore where this technology is changing the game, from high-speed trains to the roller coaster that gives you that thrilling, safe stop.

In This Article

- How Do Eddy Current Brakes Work? The Science Behind the Stop

- Types of Eddy Current Brakes

- Key Advantages of Eddy Current Brakes

- Disadvantages and Limitations

- Common Applications of Eddy Current Brakes

- Eddy Current Brakes vs. Traditional Braking Systems

- The Future of Eddy Current Braking Technology

- Your Engineering Takeaway

How Do Eddy Current Brakes Work? The Science Behind the Stop

At its heart, an eddy current brake is a deceptively simple device that performs a complex task. It doesn’t use pads, shoes, or hydraulic fluid. Instead, it relies on a fundamental principle of physics discovered by Michael Faraday in the 1830s: electromagnetic induction.

The Fundamental Principle: Electromagnetic Induction & Lenz’s Law

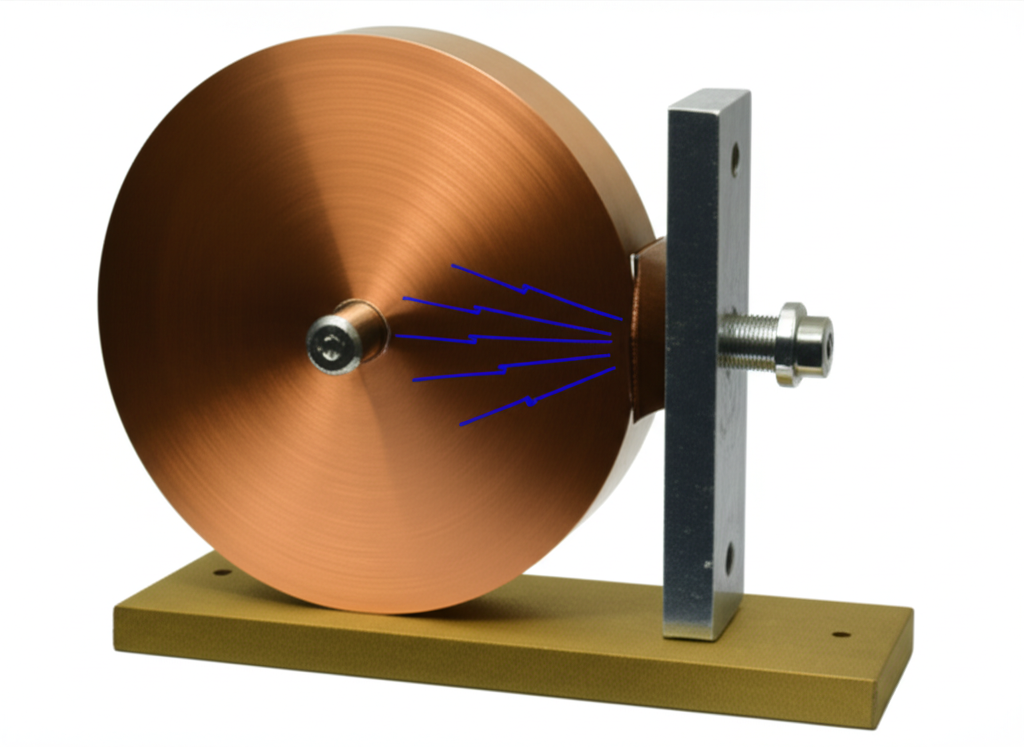

Imagine you have a solid, conductive metal disc—like one made of copper or aluminum—spinning freely. Now, bring a powerful magnet close to the edge of that spinning disc. Something amazing happens: the disc slows down as if it were moving through thick honey. No physical contact was made, yet a powerful braking force was generated.

What’s really going on? This is the core of how eddy current brakes work.

This drag is the braking force. It converts the kinetic energy of the moving object (motion) directly into thermal energy (heat) within the conductive material. It’s an elegant way to stop something without ever touching it.

Key Components of an Eddy Current Brake

While the principle is universal, the physical components are straightforward. Every eddy current brake has four main parts:

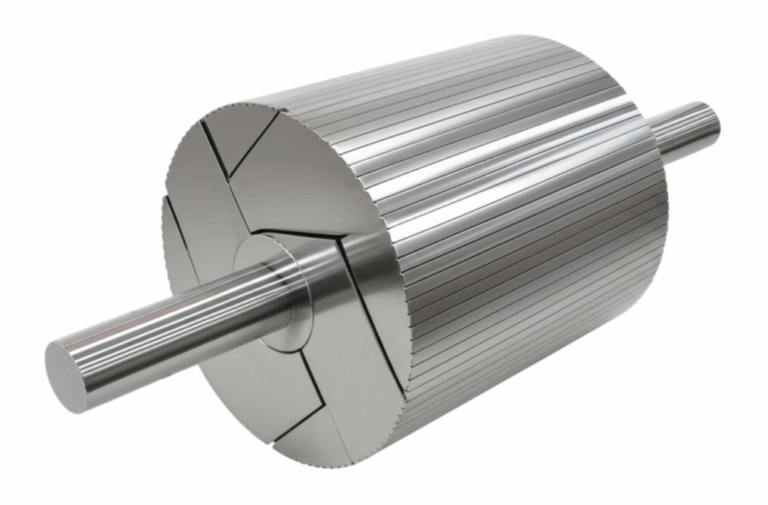

- Rotor: This is the moving part of the system. It’s typically a disc or a drum made of a highly conductive, non-ferromagnetic material like copper or aluminum. The quality of the rotor core lamination is crucial for managing the heat and electrical currents efficiently.

- Stator: This is the stationary part that generates the magnetic field. It holds the magnets and is positioned close to the rotor, but never touches it. The design of the stator determines how the magnetic field is applied to the rotor.

- Magnets: These are the source of the magnetic field. They can be either permanent magnets or, more commonly in industrial applications, electromagnets (coils of wire that become magnetic when electricity passes through them).

- Air Gap: This is the small, precise space between the stator and the rotor. The entire principle of contactless braking depends on this gap. The strength of the braking force is highly sensitive to the size of this air gap—the smaller the gap, the stronger the braking effect.

The Braking Process Explained Step-by-Step

Let’s put it all together. Here’s the sequence of events when an eddy current brake engages:

Types of Eddy Current Brakes

Not all eddy current brakes are created equal. They are generally categorized by how they generate their magnetic field and their physical configuration, which dictates their best-fit applications.

Passive Eddy Current Brakes (Permanent Magnets)

Passive systems use strong permanent magnets (like neodymium magnets) to create a fixed, constant magnetic field. They are simple, reliable, and don’t require an external power source to function.

- How they work: The braking force is entirely dependent on the relative speed between the rotor and the magnet. The faster the rotor moves, the stronger the induced eddy currents, and thus the stronger the braking force. As the rotor slows down, the braking force naturally diminishes, becoming zero when the rotor stops completely.

- Use cases: Their simplicity and fail-safe nature make them perfect for applications like roller coaster braking systems, elevators, and some types of fitness equipment where a predictable, speed-dependent deceleration is desired.

Active Eddy Current Brakes (Electromagnets)

Active systems use electromagnets—coils wrapped around a ferrous core—to generate the magnetic field. This is a game-changer because the strength of the magnetic field can be precisely controlled.

- How they work: By varying the amount of electrical current sent to the electromagnet coils, you can adjust the magnetic field strength on the fly. This gives you direct control over the braking torque, independent of the rotor’s speed (within its operational range).

- Use cases: This level of control is essential for heavy-duty applications. You’ll find them in high-speed trains, as auxiliary brakes (retarders) in large trucks and buses, and in industrial dynamometers used for testing engines and motors. The design of the stator core lamination in these systems is critical for managing the magnetic flux and efficiency.

Linear vs. Rotational Eddy Current Brakes

The concept can be applied to two different types of motion:

- Rotational Brakes: This is the more common design, where a conductive disc or drum rotates through a magnetic field. They are used to control the speed of rotating shafts in everything from industrial machinery to exercise bikes.

- Linear Brakes: Instead of a spinning disc, a linear brake uses a long, conductive rail (often attached to the vehicle) that passes through a magnetic field generated by a stator on the track (or vice-versa). This is the technology used in high-speed trains and some roller coasters to provide smooth, powerful braking without touching the rails.

Key Advantages of Eddy Current Brakes

Engineers choose eddy current brakes because they solve many of the inherent problems associated with friction-based systems. Their benefits are significant, especially in demanding environments.

Contactless & Wear-Free Operation

This is the most significant advantage. Because nothing physically touches, there are no brake pads or discs to wear out. This drastically reduces maintenance requirements and costs. A well-designed eddy current retarder on a truck can last the lifetime of the vehicle, whereas conventional brakes require regular, costly replacement. It also means no brake dust, which is a growing environmental concern.

Smooth and Quiet Braking

The braking force is generated by magnetic fields, resulting in a completely smooth, continuous, and silent deceleration. There’s no shuddering, grabbing, or screeching associated with friction brakes, leading to improved comfort for passengers and a quieter operating environment.

High Reliability & Low Maintenance

With no wearing parts and a simple mechanical design (especially in passive systems), eddy current brakes are exceptionally reliable. Maintenance often consists of little more than ensuring electrical connections are secure (on active systems) and keeping the unit clean. This high uptime is a massive benefit for commercial and industrial applications.

Precision Control (Active Systems)

For active electromagnetic brakes, the ability to modulate the braking force with high precision is a powerful tool. This allows for automated control systems, smoother stops, and the ability to hold a constant speed on a downhill grade, a feature used extensively in heavy vehicle retarders.

Effective at High Speeds

Unlike friction brakes, which can overheat and lose effectiveness (“brake fade”) during high-speed stops, eddy current brakes thrive at high speeds. The braking force naturally increases with speed, making them ideal for decelerating objects from very high velocities, which is why they are the primary choice for bullet trains and hyperloop development.

Disadvantages and Limitations

Despite their many advantages, eddy current brakes aren’t the perfect solution for every problem. Their unique operating principle comes with specific limitations that designers must account for.

Heat Generation

This is the biggest engineering challenge. All the kinetic energy absorbed during braking is converted directly into heat within the rotor. In heavy-duty applications, this can generate an enormous amount of thermal energy very quickly, with rotor temperatures potentially exceeding 300°C. This heat must be effectively managed with cooling systems—either air cooling (using fins) or liquid cooling—to prevent the rotor from overheating, which can reduce efficiency and cause material damage.

Reduced Effectiveness at Low Speeds

The braking force of an eddy current brake is proportional to speed. This means as the object slows down, the braking force diminishes. At very low speeds, the force becomes negligible, and at zero speed, there is no braking force at all. This is a critical limitation: an eddy current brake cannot be used as a holding brake or parking brake. It can’t hold a vehicle stationary on a hill. For this reason, they are almost always used as an auxiliary system alongside a traditional mechanical friction brake that can handle the final stop and hold the load.

Energy Consumption (Active Systems)

Active eddy current brakes require a constant supply of electrical power to energize their electromagnets. While the power consumed is typically a small fraction of the braking power being dissipated (a truck retarder might use 1-2 kW of electricity to handle hundreds of kilowatts of braking energy), it is still a continuous energy draw that must be supplied by the vehicle’s electrical system.

Cost and Weight Considerations

The powerful magnets (permanent or electromagnets), large conductive rotors, and necessary cooling systems can make eddy current brakes heavier and more expensive upfront than comparable friction brake systems. For example, an eddy current retarder for a heavy truck can add 100-200 kg to the vehicle’s weight. However, this initial cost is often recouped over the vehicle’s lifetime through drastically reduced maintenance and service brake replacement costs.

Common Applications of Eddy Current Brakes

You can find this clever technology in a surprising number of places, often working silently in the background to ensure safety and control.

High-Speed Rail & Roller Coasters

For vehicles moving at extreme speeds, eddy current brakes are a perfect fit. High-speed trains like the Japanese Shinkansen and French TGV use linear eddy current brakes for smooth, powerful deceleration from speeds over 300 km/h without wearing out their wheels or tracks. Similarly, roller coasters use fins on the car that pass through permanent magnet arrays to provide a reliable, fail-safe final stop.

Heavy Duty Vehicles (Trucks, Buses)

Often called “retarders,” active eddy current brakes are used as an auxiliary braking system on heavy trucks and buses. They are invaluable for navigating long, steep downhill grades. The retarder does most of the braking work, keeping the primary friction brakes cool and ready for an emergency stop. This single application can reduce service brake wear by up to 80%, saving fleet operators thousands in maintenance costs.

Industrial Machinery & Dynamometers

In industrial settings, eddy current brakes are used to control the speed of large rotating machinery. They are also the core component of engine and motor dynamometers. By applying a controlled braking force to an engine’s output shaft, a “dyno” can measure its torque and horsepower across its entire RPM range. The design of these systems often relies on high-quality motor core laminations to ensure accurate and repeatable performance.

Fitness Equipment & Elevators

The smooth, adjustable resistance in high-end stationary bikes and elliptical trainers is often provided by an eddy current brake. It allows for a silent workout with precisely controlled difficulty. In elevators, they are used as a safety mechanism to ensure a smooth, controlled stop.

Eddy Current Brakes vs. Traditional Braking Systems

To fully appreciate the role of eddy current brakes, it’s helpful to compare them directly to the other major braking technologies.

Comparison with Friction Brakes

| Feature | Eddy Current Brake | Friction Brake |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Electromagnetic drag | Mechanical friction |

| Wear | Virtually none | High (pads, rotors wear out) |

| Maintenance | Very low | High (regular replacement) |

| Noise | Silent | Can be noisy (squealing) |

| Performance | Best at high speeds; no fade | Can fade at high temps |

| Holding Ability | None at zero speed | Excellent |

| Control | Highly precise (active systems) | Less precise |

Comparison with Regenerative Braking

Regenerative braking is another advanced, contactless braking method, commonly found in electric and hybrid vehicles. The key difference lies in what happens to the energy.

- Eddy Current Brake: Converts kinetic energy into heat and dissipates it. It’s an energy dissipation system.

- Regenerative Brake: A motor is run in reverse to act as a generator, converting kinetic energy into electricity that can be stored in a battery or capacitor. It’s an energy recovery system.

While regenerative braking is more energy-efficient, it is more complex and its effectiveness depends on the battery’s state of charge. Eddy current brakes are simpler and can provide consistent braking regardless of battery level, making them excellent for safety-critical auxiliary systems.

The Future of Eddy Current Braking Technology

Research in eddy current braking continues to focus on a few key areas:

- Advanced Materials: Developing new conductive alloys and composites that can handle higher temperatures and offer better conductivity to improve braking efficiency.

- Improved Cooling: Designing more efficient air and liquid cooling systems to increase the power density and allow for more compact brake designs.

- Smart Integration: Integrating active eddy current brakes with advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) in vehicles to provide automated, predictive braking for enhanced safety.

Your Engineering Takeaway

Eddy current brakes represent a brilliant application of fundamental physics to solve a very real engineering problem. They offer a powerful, reliable, and low-maintenance solution for controlling motion, especially in high-speed, high-duty-cycle applications where traditional friction brakes would falter.

Here are the key points to remember when considering this technology for your design:

- They are contactless and wear-free, making them ideal for reducing long-term operating costs.

- Their primary limitation is heat, which must be actively managed in any demanding application.

- They are not holding brakes. They must be paired with a mechanical brake for final stopping and parking.

- Active systems offer unparalleled control, while passive systems offer fail-safe simplicity.

By understanding both the powerful advantages and the clear limitations of eddy current brakes, you can make an informed decision about whether this silent, invisible force is the right solution for your next engineering challenge.