What is Eddy Current Damping? Understanding the Physics and Applications

As an engineer or designer, you constantly face the challenge of controlling motion. Whether it’s bringing a high-speed train to a smooth stop, stabilizing a sensitive measuring instrument, or preventing a spinning component from over-speeding, the method you choose has profound implications for performance, reliability, and long-term cost. Traditional friction-based systems have their place, but they come with inherent drawbacks: wear and tear, maintenance downtime, and often noisy, jerky operation.

If you’ve ever found yourself searching for a more elegant, reliable, and maintenance-free solution for braking or damping, you’re in the right place. Eddy current damping offers a fascinating and highly effective alternative, using the fundamental principles of electromagnetism to control motion without a single physical contact. This guide is designed to walk you through exactly what it is, how it works, and where it can be the perfect fit for your next project.

What We’ll Cover

- The Fundamental Physics: A clear breakdown of how eddy current damping works, from Faraday’s Law to the final damping force.

- Key Components and Variables: The essential elements required and the factors you can tweak to control the damping strength.

- Real-World Applications: A tour of where this technology shines, from massive roller coasters to microscopic instruments.

- The Engineering Trade-Offs: A balanced look at the significant advantages of eddy current damping.

- Understanding the Limitations: An honest discussion of when to consider alternative damping methods.

- Your Engineering Takeaway: A concise summary to help you make an informed design decision.

The Fundamental Physics: How Eddy Current Damping Works

At its heart, eddy current damping is a masterful application of 19th-century physics principles discovered by scientific giants like Michael Faraday and Heinrich Lenz. It feels almost magical—creating a braking force out of thin air—but it’s grounded in three core concepts: electromagnetic induction, current generation, and force interaction.

Think of it as a three-act play.

Act 1: Electromagnetic Induction (Faraday’s Law)

The story begins with Faraday’s Law of Induction. This law states that if you change the magnetic field passing through a conductive loop, you’ll induce a voltage, or electromotive force (EMF), in that loop. The key word here is change. A stationary magnet next to a stationary piece of copper does nothing. But the moment you introduce relative motion—moving the magnet, the copper, or both—the magnetic field experienced by the conductor changes. This changing magnetic flux is the trigger for everything that follows.

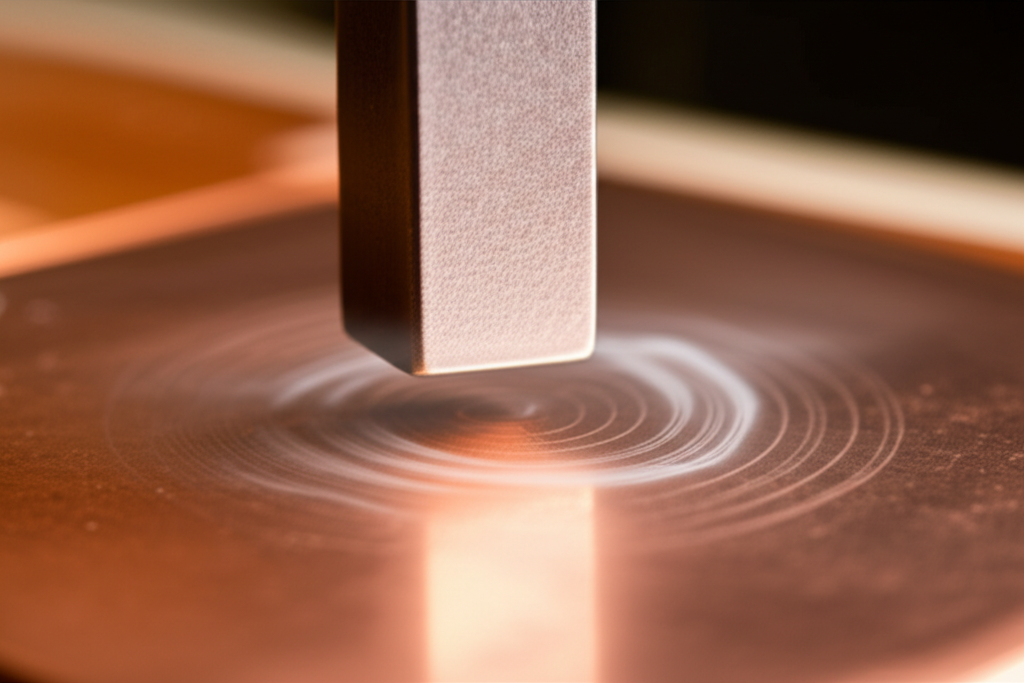

Imagine dragging a strong magnet over a sheet of copper. As the magnet moves, different parts of the copper sheet experience a magnetic field that grows stronger as the magnet approaches and weaker as it moves away. This continuous change is the engine of eddy current damping.

Act 2: Eddy Current Generation (Lenz’s Law)

This induced voltage needs somewhere to go. In a simple wire, it would drive a current from one end to the other. But in a solid conductive plate or disc, the voltage creates localized, circular paths of electrical current within the material itself. These swirling, closed-loop currents are what we call eddy currents.

You can visualize them as small, invisible whirlpools of electricity spinning inside the conductor. Their existence is a direct consequence of Faraday’s Law.

Now, here’s where it gets clever. According to Lenz’s Law, these newly created eddy currents will flow in a direction that generates their own magnetic field, and this new magnetic field will oppose the very change that created it. It’s nature’s way of maintaining equilibrium. The conductor essentially says, “Hey, I don’t like this changing magnetic field you’re imposing on me, so I’m going to create my own magnetic field to fight back.”

Act 3: The Damping Force (Lorentz Force)

This “fight” is what produces the physical braking effect. You now have two magnetic fields interacting: the original field from the magnet and the opposing field generated by the eddy currents. This interaction creates a physical force known as the Lorentz force.

This force acts on the moving conductor in the opposite direction of its motion, creating a magnetic drag. It’s this drag that slows the object down.

The final piece of the puzzle is energy conversion. Where does the motion energy (kinetic energy) go? It’s not destroyed; it’s transformed. The kinetic energy of the moving object is first converted into electrical energy in the form of eddy currents. As these currents swirl through the conductor—which has its own electrical resistance—that electrical energy is dissipated as heat (a phenomenon called Joule or Ohmic heating).

So, in essence, eddy current damping is a highly efficient process for converting unwanted kinetic energy into heat, which is then safely dissipated into the environment. All of this happens silently and without any physical contact.

Key Components and Variables That Define the System

To implement eddy current damping, you only need three fundamental things. However, the effectiveness of the system depends on several key variables that engineers can manipulate to achieve the desired performance.

The Essential Trio: Conductor, Magnet, and Motion

- Permanent Magnets: Made from materials like Neodymium or Samarium-cobalt, these provide a constant magnetic field without any power input. This makes them incredibly reliable and fail-safe, which is why they’re used in safety-critical applications like roller coaster brakes.

- Electromagnets: These are coils of wire that become magnetic when an electrical current is passed through them. Their biggest advantage is controllability. By varying the current, you can adjust the strength of the magnetic field and, therefore, the damping force, in real-time. This is ideal for applications like exercise equipment or dynamometers.

Factors Influencing Damping Strength

If you need to fine-tune the braking effect, you can adjust four primary factors:

- Strength of the Magnetic Field: This is the most direct relationship. Double the magnetic field strength (B), and you’ll get a significantly stronger damping force. Using more powerful magnets or increasing the current to an electromagnet is a primary way to boost performance.

- Speed of Relative Motion: The damping force is generally proportional to the velocity. The faster the conductor moves through the magnetic field, the greater the rate of change of magnetic flux, which induces stronger eddy currents and a more powerful braking force. This creates a wonderful self-regulating effect: the faster something is moving, the harder the system brakes. However, at extremely high speeds, the effect can plateau or even decrease.

- Conductivity of the Material: A material with higher electrical conductivity (like copper over aluminum) will allow for the formation of larger eddy currents for the same induced voltage, resulting in a stronger opposing magnetic field and a greater damping force. The management of these currents is a core principle in the design of efficient electrical steel laminations.

- Geometry and Thickness of the Conductor: A thicker conductive material provides more volume for eddy currents to flow, reducing the material’s overall resistance and increasing the damping force. Similarly, the shape and path of the conductor through the magnetic field can be optimized to maximize the interaction.

Real-World Applications: Where Eddy Current Damping Shines

The elegance and reliability of eddy current damping have made it a go-to solution in a surprisingly diverse range of fields, from massive industrial machinery to high-precision scientific instruments.

High-Impact Braking Systems

When smooth, consistent, and maintenance-free braking is required, eddy currents are often the best answer.

- Roller Coasters and Theme Park Rides: This is a classic example. Look at the end of a modern roller coaster’s track, and you’ll often see rows of powerful permanent magnets. As copper or aluminum fins attached to the train pass through these magnets, a powerful but incredibly smooth braking force is generated, bringing the train to a safe stop without the jolt or squeal of friction brakes. Because it’s a non-contact system, its performance isn’t affected by rain or snow, and there are no brake pads to wear out.

- High-Speed Trains: Trains like the Shanghai Maglev, which can reach speeds over 430 km/h (268 mph), rely on eddy current braking as a primary or supplementary system. It allows for controlled deceleration from very high velocities without the immense wear and heat that would destroy conventional brakes.

- Industrial Machinery: In factories, eddy current brakes are used to control the speed of large rotating equipment like flywheels, paper mill rollers, and industrial centrifuges. They provide a reliable way to decelerate heavy loads smoothly and prevent damage.

Precision in Scientific and Commercial Instruments

On the other end of the scale, eddy current damping is essential for achieving stability and accuracy in sensitive devices.

- Weighing Scales and Analytical Balances: When you place an object on a high-precision scale, you want a quick, stable reading. Any oscillation of the balance mechanism can delay and compromise the measurement. A small aluminum vane attached to the balance arm is often designed to pass between the poles of a small magnet. This tiny eddy current damper quickly eliminates any overshoot or “wobble,” allowing the display to settle almost instantly. This can reduce settling time from several seconds to under a second.

- Galvanometers and Analog Meters: In older analog instruments, the pointer needle could easily swing past the correct reading and oscillate back and forth. To prevent this, the coil was often wound on a lightweight aluminum frame. As the frame and coil rotated within the instrument’s permanent magnet, eddy currents were induced in the frame, damping the needle’s movement and bringing it to a swift, clean stop.

- Vibration Damping in Sensitive Equipment: For equipment like atomic force microscopes, optical tables, or high-precision manufacturing tools, even the slightest vibration can ruin an experiment or a product. Eddy current dampers are integrated into these systems to dissipate vibrational energy, creating an ultra-stable environment. The principles of minimizing unwanted electrical and magnetic effects are also central to the design of high-quality motor core laminations for precision applications.

Other Notable Uses

- Fitness Equipment: The resistance knob on many high-end magnetic exercise bikes and ellipticals controls the current flowing to an electromagnet. Increasing the current strengthens the magnetic field interacting with a spinning conductive flywheel, which increases the eddy current braking force and makes it harder to pedal.

- Electromagnetic Dynamometers: When testing the torque and power output of an engine or electric motor, a dynamometer is used to apply a controllable load. Eddy current dynamometers are a popular choice because they can apply a very precise and rapidly adjustable braking torque to the output shaft, allowing engineers to map performance across a range of speeds and loads.

The Engineering Trade-Offs: Advantages of Eddy Current Damping

Choosing eddy current damping for a design brings a host of compelling benefits, especially when compared to friction-based alternatives.

- Non-Contact Operation: This is the headline advantage. Since nothing physically touches, there is no wear and tear. This translates directly to an extremely long operational life and drastically reduced maintenance needs. A study of industrial applications showed that eddy current systems can reduce maintenance costs and downtime by over 80% compared to equivalent friction brakes.

- Smooth and Silent Braking: The damping force is inherently smooth and progressive, free from the shuddering or grabbing that can occur with friction systems. The operation is also nearly silent, a significant benefit for user-facing products and sensitive environments.

- High Reliability and Fail-Safety: Systems using permanent magnets are incredibly reliable because they require no external power to function. They are “always on,” making them an excellent choice for safety-critical emergency braking systems.

- Clean Operation: With no friction, there are no brake pads to grind down. This means no dust or fine particulate byproducts are created, making eddy current damping ideal for cleanroom environments, medical devices, and food processing machinery.

- Speed-Proportional Damping: The braking force naturally increases with speed, creating a self-regulating system. It provides strong damping when needed most (at high speeds) and gently fades as the system slows down.

- Precise and Controllable Force: When using electromagnets, the damping force can be controlled with high precision by simply adjusting the input current. This allows for dynamic, real-time adjustments to braking torque.

Understanding the Limitations: When to Consider Alternatives

Despite its many advantages, eddy current damping isn’t a universal solution. It has specific characteristics that make it unsuitable for certain tasks.

- Significant Heat Generation: All the kinetic energy absorbed by the system is converted into heat within the conductor. In heavy-duty or high-frequency braking applications, this heat can be substantial. The design must account for this thermal load, often requiring cooling fins, forced air, or even liquid cooling systems to prevent the conductor from overheating and losing effectiveness.

- Requires Relative Motion for Braking: This is a crucial limitation to understand. Eddy current damping produces zero force at zero speed. Therefore, it can slow a load down, but it cannot hold it stationary. For applications requiring a “parking brake” or holding a load against gravity, an eddy current brake must be paired with a mechanical friction brake. The interaction between moving and stationary parts is a key design consideration, much like it is when engineering the relationship between a stator and rotor.

- Lower Force at Low Speeds: While the speed-proportional nature is often an advantage, it also means the braking force can be quite weak just before the object comes to a complete stop. For applications needing aggressive, hard stops, a friction brake is often superior.

- Not a Regenerative System: Unlike regenerative braking in electric vehicles, where kinetic energy is converted back into stored electrical energy to charge a battery, eddy current damping dissipates the energy as waste heat. It is a purely dissipative system.

Your Engineering Takeaway: Making an Informed Decision

Eddy current damping is a powerful and elegant engineering tool that leverages the fundamental laws of electromagnetism to provide smooth, silent, and exceptionally reliable braking and damping without physical contact. By inducing swirling currents within a moving conductor, it creates a magnetic drag that converts unwanted motion into manageable heat.

When deciding if this technology is the right fit for your application, consider these key points:

- Core Benefit: Its primary advantages are zero wear, minimal maintenance, and smooth, silent operation. If these are your top design priorities, eddy current damping should be a leading contender.

- Best-Fit Applications: It excels in high-speed deceleration (trains, roller coasters), precision stabilization (scales, scientific instruments), and controllable resistance (fitness equipment, dynamometers). The material science behind these systems, particularly the use of specialized silicon steel laminations in related motor technologies, is a field of constant innovation.

- Critical Limitations: Remember that it cannot hold a load stationary and that managing the heat generated is a critical design consideration for heavy-duty applications.

By understanding these principles, advantages, and limitations, you are empowered to make a more informed decision, select the right technology for your needs, and engage in more productive conversations with suppliers and partners. Eddy current damping is a testament to how fundamental physics can be harnessed to solve complex modern engineering challenges.