What is the Difference Between Sensory and Motor Neurons? Understanding the Nervous System’s Key Players

Table of contents

- Introduction

- The Neuron: A Quick Overview

- What is a Neuron?

- The Nervous System’s Information Highway

- Sensory Neurons (Afferent Neurons): The Messengers from the World

- Definition and Primary Function

- Key Structural Characteristics

- Location and Pathway

- Examples in Action

- Motor Neurons (Efferent Neurons): The Command Dispatchers

- Definition and Primary Function

- Key Structural Characteristics

- Location and Pathway

- Examples in Action

- Key Differences: Sensory vs. Motor Neurons (Direct Comparison)

- Function (Input vs. Output)

- Direction of Signal Transmission

- Typical Structure

- Location of Cell Body

- Associated Structures

- Myelination and Conduction Speed

- The Role of Interneurons: Connecting the Circuit

- How They Work Together: The Reflex Arc and Beyond

- The Reflex Arc Explained

- Orchestrating Voluntary Actions

- Clinical Significance: When Sensory or Motor Neurons Are Affected

- Conclusion

- FAQs about Sensory and Motor Neurons

Introduction

I still remember the first time I learned the words afferent and efferent. They sounded like twins who dressed alike and swapped places. Then I learned a simple trick. Sensory neurons arrive at the central nervous system. Motor neurons exit. Arrive and Exit. Afferent and Efferent. That little mnemonic stuck with me through every lab, every reflex test, and every time someone asked about the difference between sensory and motor neurons.

In this guide I’ll walk you through the essentials. You’ll see how these nerve cells handle input and output. You’ll see how their structure fits their job. You’ll also see how they team up with interneurons to wire up reflexes and voluntary movement. I’ll draw on real examples you know well. Touching a hot pan. Lifting your arm. Blinking when a speck of dust hits your eye. Along the way I’ll keep the language simple and the comparisons clear. If you love details, you’ll find plenty here. If you just want the bottom line, you’ll get that too.

The Neuron: A Quick Overview

What is a Neuron?

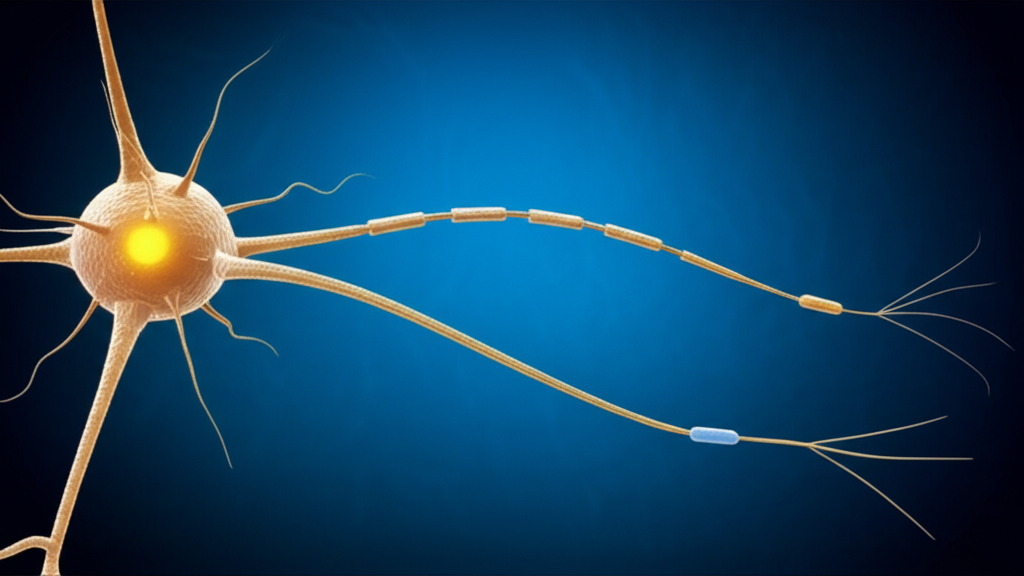

I like to think of a neuron as a tiny, excitable messenger that uses electricity and chemistry to share news. A neuron is a specialized nerve cell that transmits signals. It fires an electrical impulse called an action potential down a long projection called the axon. It receives input on branch-like structures called dendrites. It keeps the lights on with a cell body, also called the soma.

- Dendrites: input branches that collect signals from receptors or other neurons.

- Cell body (soma): the metabolic center that integrates incoming signals.

- Axon: the output wire that carries the action potential toward axon terminals.

- Synapse: the gap where one neuron talks to the next using neurotransmitters like glutamate, GABA, acetylcholine, dopamine, serotonin, noradrenaline, and adrenaline.

The Nervous System’s Information Highway

Your nervous system splits into two big regions. The Central Nervous System (CNS) includes the brain and spinal cord. The Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) includes the nerves that leave the CNS and roam the body. Neurons organize into circuits. Inside the CNS, we talk about gray matter (cell bodies, dendrites, synapses) and white matter (myelinated axons). Bundles of axons in the CNS are called tracts. Bundles in the PNS are called nerves. Groups of cell bodies in the CNS are nuclei. Groups in the PNS are ganglia.

That vocabulary matters. Because the location and wiring of sensory and motor neurons tell you exactly what job each one performs.

Sensory Neurons (Afferent Neurons): The Messengers from the World

Definition and Primary Function

Sensory neurons carry information from the world to you. They transmit signals from sensory receptors in the periphery to the CNS. They allow sensation. Touch, pressure, vibration, pain (nociception), temperature (thermoreception), proprioception (joint and muscle position), taste and smell (chemoreception), and light (photoreception). If you feel a pinprick or sense your ankle position with your eyes closed, thank your sensory neurons.

Key Structural Characteristics

Most sensory neurons that feed your spinal cord are pseudounipolar. Their cell body sits off to the side like a little bulb. One process leaves the soma and splits into two branches. One heads toward the periphery as a long dendritic-like process that connects to sensory receptors. The other heads toward the spinal cord as the axon. In special senses like retina and olfactory epithelium you might find bipolar neurons. That structure streamlines input from a single receptor field and lets the neuron send the signal toward the CNS with minimal synaptic delay.

These cells often carry long processes from far-away skin or joints toward the spinal cord. Many of those processes are myelinated by Schwann cells in the PNS. Myelin works like electrical insulation. It speeds up the nerve impulse. Some sensory fibers run blazing fast. Proprioceptive fibers and some mechanoreceptors can reach conduction velocities near 80–120 m/s. Unmyelinated C fibers carry slow, dull, chronic pain. They might trundle along at 0.5–2 m/s.

Location and Pathway

Here’s the path I picture. A stimulus activates a receptor in the periphery. The sensory neuron’s peripheral process picks it up and becomes the electrical messenger. The impulse travels toward the dorsal root ganglion. That’s where the cell body lives. Then the central process enters the spinal cord through the dorsal root and synapses in the dorsal horn or heads up toward the brain along ascending tracts.

- Origin: sensory receptors in skin, muscles, joints, eyes, ears, tongue, nose, and viscera.

- Cell body: dorsal root ganglia (for body) or cranial sensory ganglia.

- Destination: spinal cord dorsal horn or brainstem nuclei, then onward to higher centers like the somatosensory cortex.

Examples in Action

- Touching a hot stove: Thermoreceptors and nociceptors detect high temperature and tissue threat. Sensory neurons rush that message to your spinal cord.

- Seeing a bright light: Photoreceptors in the retina pass signals to bipolar and ganglion cells that send action potentials along the optic nerve toward the brain.

- Hearing your name: Hair cells in the cochlea mechanically transduce sound waves. The auditory pathway carries those signals centrally.

Motor Neurons (Efferent Neurons): The Command Dispatchers

Definition and Primary Function

Motor neurons carry commands from your CNS to effectors. They make muscles contract and glands secrete. Without them you could think about moving all day, yet nothing would budge. Motor neurons handle output. They turn decisions into action.

Key Structural Characteristics

Lower motor neurons that directly innervate skeletal muscle are multipolar. They have many dendrites and one axon. That geometry makes sense. Each motor neuron integrates many inputs from interneurons and descending tracts. Then it fires a final decision down its axon to the muscle. The axon can be very long. Think about the journey from your spinal cord to your toes. Myelin sheaths wrap these axons to speed conduction. Fast motor control depends on speed and precision.

At the muscle, the axon branches into terminals that contact the motor end plate at the neuromuscular junction. Acetylcholine gets released there. It binds receptors on the muscle membrane and triggers muscle contraction.

Location and Pathway

When I trace the wiring in my head, I see two levels. Upper motor neurons live in the motor cortex and brainstem. They send commands down descending tracts to lower motor neurons. Lower motor neurons live in the ventral horn of the spinal cord or motor nuclei of cranial nerves. Those lower motor neurons project out via ventral roots and peripheral nerves to muscles and glands.

- Origin: CNS (motor cortex, brainstem nuclei, spinal cord ventral horn).

- Cell body: within the CNS for lower motor neurons.

- Destination: skeletal muscle fibers, smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, or glands via the PNS.

Examples in Action

- Lifting your arm: Signals begin in the motor cortex. They descend to the spinal cord. Lower motor neurons in the ventral horn fire. Your biceps contracts.

- Blinking: The facial nerve’s motor fibers trigger orbicularis oculi to close your eyelids.

- Digestion: Autonomic motor neurons coordinate smooth muscle contraction in the gut and gland secretion to move and digest food.

Key Differences: Sensory vs. Motor Neurons (Direct Comparison)

Function (Input vs. Output)

- Sensory (afferent): carry sensory input to the CNS for processing and perception.

- Motor (efferent): carry output commands from the CNS to effectors to produce movement or secretion.

Direction of Signal Transmission

- Sensory: from periphery to CNS.

- Motor: from CNS to periphery.

Typical Structure

- Sensory: often pseudounipolar or bipolar for streamlined input. Cell body sits off to the side.

- Motor: multipolar with many dendrites to integrate many signals before issuing a command.

Location of Cell Body

- Sensory: in ganglia outside the CNS such as the dorsal root ganglia.

- Motor: within the CNS such as the ventral horn of the spinal cord or brainstem motor nuclei.

Associated Structures

- Sensory: link to sensory receptors like mechanoreceptors, nociceptors, thermoreceptors, chemoreceptors, and photoreceptors.

- Motor: link to effectors like skeletal muscle, smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and glands via the neuromuscular junction.

Myelination and Conduction Speed

- Sensory: range from heavily myelinated proprioceptive fibers to unmyelinated pain fibers. Conduction speeds vary from about 0.5 m/s to over 80 m/s depending on fiber type.

- Motor: often heavily myelinated for fast voluntary control. Large motor fibers can conduct near 60–120 m/s.

If you remember only one thing, remember the traffic flow. Sensory neurons bring information in. Motor neurons send commands out. Input versus output. Afferent versus efferent.

The Role of Interneurons: Connecting the Circuit

Interneurons live entirely within the CNS. They connect sensory input to motor output. They handle integration. Many sit in the dorsal and ventral horns of the spinal cord and in brainstem nuclei. Others form complex networks in the cortex. In a reflex arc they can make a split-second decision. In voluntary movement they shape and refine motor programs using sensory feedback.

I think of interneurons as editors. Sensory messages arrive raw. Interneurons shape them. They emphasize important bits and damp down noise through excitatory neurotransmitters like glutamate and inhibitory ones like GABA or glycine. Then they pass polished instructions to motor neurons. That’s how you get a clean and coordinated movement instead of chaos.

How They Work Together: The Reflex Arc and Beyond

The Reflex Arc Explained

When I tap a tendon with a reflex hammer, I see a beautiful loop in action. The path looks simple.

- Receptor: a muscle spindle senses sudden stretch.

- Sensory neuron: a proprioceptive afferent fires quickly into the spinal cord.

- Interneuron: sometimes present, sometimes bypassed.

- Motor neuron: the alpha motor neuron in the ventral horn fires.

- Effector: the stretched muscle contracts to resist stretch.

That’s the stretch reflex in a nutshell. It runs fast and often uses a monosynaptic route from sensory neuron to motor neuron. The patellar tendon reflex is the classic example. Other reflex arcs like withdrawal reflexes recruit interneurons that coordinate flexors and inhibit extensors. These circuits live in the spinal cord. They run without waiting for the brain because speed matters when your finger meets a hot stove.

Orchestrating Voluntary Actions

Voluntary movement runs a bigger show. The motor cortex plans and initiates. The basal ganglia and cerebellum help sequence and coordinate. Descending tracts carry commands down the spinal cord. Interneurons blend those commands with ongoing sensory input like proprioception from muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs. Lower motor neurons send the final word to muscles through the neuromuscular junction. While you reach for a glass, sensory feedback tells the CNS how heavy it feels. The CNS adjusts grip force on the fly.

I like to compare this to an electric motor system because the analogy helps. In an electric motor, the controller issues commands, the sensor reads position or speed, and the plant (stator and rotor) turns those commands into motion. If you’re curious about the hardware side of that analogy, this explainer on stator and rotor basics will give you a quick visual for how paired parts create motion in machines. Your nervous system does the same thing with biological parts. Cortex and spinal circuits play controller. Sensory receptors act as sensors. Muscles and glands act as effectors.

That motor analogy goes a bit further. Electric motors obey fundamental rules of electromagnetic conversion. If you want a refresher on that, here’s a short primer on the motor principle. In your body, neurons obey membrane physics and ion channel rules. Different arena, same idea. Principles guide consistent results.

One more analogy helps when you think about speed. Engineers reduce energy loss in motors using laminated cores. Those electrical steel laminations limit eddy currents and boost efficiency. Neurons reduce loss and speed up signals with myelin sheaths. Different materials, same goal. Keep the signal fast and clean.

Clinical Significance: When Sensory or Motor Neurons Are Affected

You feel the difference between sensory and motor neurons most acutely when something goes wrong. Damage on the sensory side looks different than damage on the motor side. When I teach this, I ask two questions. What do you feel, and what can you do? Sensory problems change what you feel. Motor problems change what you can do.

Sensory neuron problems

- Peripheral neuropathy: Common in diabetes and other metabolic disorders. Patients report numbness, tingling, burning pain, or loss of sensation in a “stocking-glove” pattern. The issue often involves damage to sensory fibers. People might injure their feet and not notice. Neuropathies affect a meaningful chunk of the population. Estimates often range from roughly 2% to 8% depending on age and risk factors.

- Shingles (herpes zoster): Reactivation of varicella-zoster virus in dorsal root ganglia. It inflames sensory neurons and causes a painful, blistering rash along a dermatomal distribution.

- Sensory ataxia: Loss of proprioception leads to unsteady gait and heavy reliance on vision to guide movement. You see a positive Romberg sign because the person sways with eyes closed.

Motor neuron problems

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): This disease selectively targets motor neurons. Patients develop progressive muscle weakness, atrophy, fasciculations, and spasticity. Cognition and sensation often remain intact because sensory pathways stay relatively spared. In the United States, tens of thousands of people live with ALS at any given time, with many estimates landing around thirty thousand.

- Polio: The poliovirus targets motor neurons in the spinal cord and can cause flaccid paralysis.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome: An acute demyelinating polyneuropathy that can affect motor fibers and cause ascending weakness. Many cases also involve sensory changes.

- Motor injuries: Trauma to ventral roots or peripheral motor fibers causes weakness and atrophy in the affected myotomes.

Mixed or central conditions

- Multiple sclerosis (MS): Demyelination within the CNS can hit sensory and motor tracts. That produces a mix of symptoms. Numbness, weakness, spasticity, visual loss, and more. MS shows you how myelin matters for both sides of the house.

- Parkinson’s disease: This condition mainly affects motor control circuits in the basal ganglia. It leads to bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, and postural instability. Sensory neurons are not the main target, yet sensory feedback can still influence motor symptoms.

Where symptoms map to anatomy

- Dorsal root ganglion and dorsal horn: sensory territory. Expect sensory loss, paresthesia, or neuropathic pain.

- Ventral horn and ventral roots: motor territory. Expect weakness, fasciculations, and muscle atrophy.

- Peripheral nerves: contain both sensory and motor fibers. Expect mixed deficits if the whole nerve is injured.

Why myelination and fiber type matter

When myelin suffers, conduction slows. In both sensory and motor fibers, demyelination blurs signals and creates delays. That is why MS can create wide-ranging problems. In the PNS, remyelination can happen to some degree after injury, so you sometimes see partial recovery. Axonal loss cuts deeper. Motor neuron loss often does not regenerate in the CNS. That makes conditions like ALS so devastating.

How to keep the big picture straight

- Sensory neuron damage changes perception. Numbness, tingling, pain, loss of position sense.

- Motor neuron damage changes action. Weakness, atrophy, paralysis, reduced reflexes if lower motor neuron loss predominates, or increased reflexes if upper motor neuron tracts are hit.

The Neuron: A Few More Nuts and Bolts for the Curious

I’ve found that a handful of terms tie together many exam questions. Here they are with quick notes.

- Neurotransmission: Electrical impulses ride along axons as action potentials. At synapses they convert to chemical signals when neurotransmitters cross the cleft. Presynaptic neurons release. Postsynaptic neurons listen with receptors.

- Excitatory vs. inhibitory: Glutamate often excites. GABA often inhibits. Balance keeps circuits stable.

- Somatic vs. autonomic: Somatic motor neurons control voluntary skeletal muscle. Autonomic efferents manage involuntary smooth and cardiac muscle and gland secretion to maintain homeostasis.

- Cranial nerves vs. spinal nerves: Cranial nerves connect to the brain and brainstem. Spinal nerves connect to the spinal cord. Both carry sensory input, motor output, or both depending on the specific nerve.

- Nerve vs. neuron: A neuron is a single cell. A nerve is a bundle of axons in the PNS. A tract is a bundle in the CNS.

How Structure Serves Function: A Guided Tour

When you look at a sensory neuron with a pseudounipolar shape, you see efficiency. A single process splits like a Y. One branch dives toward the skin or muscle to pick up signals from receptors. The other branches toward the spinal cord to deliver that message. Few synapses. Little processing. Straight to the point. That simplicity helps speed reliable delivery of sensory input.

When you look at a multipolar motor neuron, you see a decision maker. Dendrites fan out like a tree to collect advice from many sources. Interneurons weigh in. Descending cortical commands weigh in. Inhibitory circuits weigh in. The soma integrates this traffic. Then the axon fires a single clean decision. Contract or wait. How hard to contract. For how long.

Myelin wraps both types when speed matters. Myelinated proprioceptive afferents run fast because precise, timely feedback about limb position keeps you upright. Myelinated motor axons run fast because fine control of your fingers needs tight timing. Unmyelinated pain fibers run slow because they carry ongoing background warnings rather than split-second updates.

Putting the Cortex on the Map

- Somatosensory cortex: receives processed sensory input from the thalamus about touch, vibration, pain, temperature, and proprioception.

- Motor cortex: sends motor commands down corticospinal tracts to the spinal cord.

- Integration: Sensory feedback loops back constantly. Grip strength adjusts when a cup feels heavier than expected. Vision and proprioception team up to guide movement.

A Walk Through a Complete Pathway: From Stimulus to Response

Let me walk you through a scene that plays out every day. You step on a tack.

- Stimulus and transduction: Nociceptors in your foot transduce the mechanical insult into electrical signals. Sensory transduction turns that stimulus into an action potential.

- Afferent signal: The sensory neuron’s peripheral process carries the nerve impulse toward the dorsal root ganglion. The central process enters the dorsal horn.

- Reflex response: Interneurons in the spinal cord connect to motor neurons. The withdrawal reflex fires. Flexors contract to pull your foot away. Extensors inhibit.

- Ascending information: Other neurons relay pain up the spinal cord to the brain. Your thalamus and somatosensory cortex register sharp pain. You also form a memory and decide what to do next.

- Descending command: The motor cortex might send additional commands to shift your weight and check for bleeding. Lower motor neurons execute those adjustments.

All that happens in a blink. You get pain perception, movement, and autonomic changes like a quick heart rate jump. Sensory input and motor output dance together with interneurons calling the steps.

Common Questions I Hear When Teaching This Topic

Do sensory and motor neurons look different under the microscope?

Yes. Sensory neurons that run to the spinal cord are often pseudounipolar with a round cell body in the dorsal root ganglion and a single process that bifurcates. Motor neurons in the ventral horn are multipolar with abundant dendrites and a single large axon.

Why does cell body location matter?

Location tells you direction. A sensory neuron’s soma in the dorsal root ganglion signals PNS origin and CNS destination. A motor neuron’s soma in the ventral horn signals CNS origin and PNS destination.

What about myelination and speed?

Myelin increases conduction velocity by enabling saltatory conduction. Big, heavily myelinated fibers run fastest. Proprioception and motor control often demand speed. Slow unmyelinated fibers carry chronic pain and temperature.

What happens at the neuromuscular junction?

The motor neuron’s axon terminal releases acetylcholine. It binds to receptors on the motor end plate of the muscle fiber. That triggers depolarization and a muscle action potential which leads to contraction. Without that chemical handshake, muscles would not move.

Autonomic versus somatic motor neurons?

Somatic motor neurons drive voluntary skeletal muscle. Autonomic efferents drive involuntary smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and glands. They maintain homeostasis. Think heart rate, gut motility, pupil size, and sweat production.

Receptor types I keep straight with a simple list:

- Mechanoreceptors: touch and pressure.

- Nociceptors: pain.

- Thermoreceptors: temperature.

- Chemoreceptors: taste and smell.

- Photoreceptors: light.

- Proprioceptors: muscle spindle and Golgi tendon organ for limb position and tension.

Anatomy landmarks I never forget:

- Dorsal horn: sensory processing site in spinal gray matter.

- Ventral horn: motor neuron cell bodies in spinal gray matter.

- Dorsal root ganglion: sensory neuron cell bodies.

- Ventral root: motor fibers leaving the cord.

Best mental model

Information flows in through sensory afferents. The CNS integrates. Commands flow out through motor efferents. Inputs and outputs. Receptors and effectors. That simple model helps you file the details.

Conclusion

If you’re still with me, you have the key differences nailed down. Sensory neurons detect stimuli with specialized receptors then deliver those signals to the CNS. Motor neurons carry commands from the CNS to muscles and glands to produce movement and secretion. Structure supports function. Pseudounipolar sensory neurons streamline input. Multipolar motor neurons integrate and execute. Cell body location marks direction. Dorsal ganglia for sensory. Ventral horn for motor. Interneurons do the glue work inside the CNS. Reflex arcs show the trio in action at high speed. Voluntary movement shows the whole orchestra working in sync.

When disease strikes, symptoms split along the same lines. Sensory neuron damage changes sensation. Motor neuron damage changes movement. Mixed diseases prove that myelin and axons matter on both sides. You now have a map that connects anatomy, physiology, and clinical signs. Keep that arrive versus exit trick handy. It works when the details pile up.

FAQs about Sensory and Motor Neurons

Q: Are interneurons sensory or motor?

A: Neither. Interneurons sit within the CNS and connect sensory and motor neurons. They integrate input and shape output. They are the in-between decision makers.

Q: What happens if sensory neurons are damaged?

A: People lose or alter sensation. They might feel numbness, tingling, burning pain, or lose proprioception. Walking can become unsteady without visual cues. Reflexes that rely on sensory input can weaken.

Q: What happens if motor neurons are damaged?

A: People lose strength and control. You see weakness, atrophy, fasciculations, and changes in reflexes. Lower motor neuron damage causes flaccid weakness and reduced reflexes. Upper motor neuron pathway damage causes spasticity and increased reflexes.

Q: Do all reflexes involve interneurons?

A: No. The stretch reflex can be monosynaptic. It connects a sensory neuron directly to a motor neuron. Many other reflexes use interneurons to coordinate multiple muscles and to provide inhibition of antagonists.

Q: What is the difference between a nerve and a neuron?

A: A neuron is a single cell that carries electrical and chemical signals. A nerve is a bundle of many axons in the PNS wrapped together like a cable. In the CNS that bundle is called a tract.

Q: Where do cranial nerves fit into this?

A: Cranial nerves can carry sensory input, motor output, or both. Their sensory ganglia and motor nuclei follow the same rules. Sensory cell bodies sit in ganglia. Motor cell bodies sit in the brainstem.

Q: How do excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters matter?

A: Excitatory transmitters like glutamate make neurons more likely to fire. Inhibitory transmitters like GABA make neurons less likely to fire. Motor neurons balance both types of input before sending a command.

Q: Why do proprioceptors matter so much for movement?

A: Proprioceptors like muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs provide crucial feedback about muscle length and tension. They let the CNS adjust force and position in real time. Without them, movement feels clumsy and unsafe.

Q: Does myelin heal if damaged?

A: In the PNS, Schwann cells can remyelinate to some extent after injury. Recovery happens but may be incomplete. In the CNS, remyelination is limited. That’s why diseases like MS cause recurrent or progressive problems.

Q: Are sensory and motor neurons the only types?

A: No. Interneurons form vast networks inside the CNS. They outnumber sensory and motor neurons by a wide margin. They handle integration, pattern generation, and coordination.

Final note

If you ever get lost in the details, ask two questions. Where does the signal come from? Where is it going? If it travels toward the CNS from a receptor, you’re looking at a sensory afferent. If it heads out to muscle or gland, you’re looking at a motor efferent. That compass always points north.

Internal links used

- For a mechanical analogy to motion generation, see stator and rotor basics.

- For a short refresher on machine motion fundamentals, see the motor principle.

- For a quick look at how engineers reduce loss in motors, see electrical steel laminations.