What Makes Up a Motor Unit? Understanding the Fundamentals of Muscle Control

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Building Block of Movement

- The Core Components of a Motor Unit

- The Alpha Motor Neuron: The Command Center

- The Muscle Fibers: The Responding Team

- The Neuromuscular Junction: The Communication Bridge

- How a Motor Unit Works: From Signal to Contraction

- From Action Potential to Muscle Shortening

- The All-or-None Principle

- Types of Motor Units and Their Roles

- Slow, Fast Fatigue-Resistant, and Fast Fatigable

- Innervation Ratio: Precision vs Power

- Motor Unit Recruitment: Henneman’s Size Principle

- Rate Coding, Summation, and Tetanus

- Sensory Feedback and Control

- Muscle Spindles and Golgi Tendon Organs

- Motor Neuron Pools and CNS Control

- Clinical Significance: Health, Disease, and Assessment

- EMG Basics and What It Shows

- Neuromuscular Disorders That Impact Motor Units

- Aging, Exercise, and Motor Unit Adaptation

- Strength, Hypertrophy, and Motor Learning

- Reinnervation, Axonal Sprouting, and Remodeling

- Special Cases: Fine Control and Breathing

- Eye and Hand Muscles

- Diaphragm and Respiratory Motor Units

- Practical Tips for Students, Coaches, and Clinicians

- A Quick Analogy to Electric Motors

- Conclusion: The Orchestration Behind Every Movement

Introduction: The Building Block of Movement

I still remember the moment the idea of a motor unit clicked for me. I had been trying to understand how the nervous system turns a thought like “pick up the cup” into an actual movement. The answer felt simple once I saw it. A motor unit is the smallest functional unit of muscle contraction. One alpha motor neuron and all the skeletal muscle fibers it innervates. That’s the team. The nervous system doesn’t usually activate individual fibers one by one. It calls up motor units.

Understanding motor units helped me explain voluntary muscle contraction, reflexes, coordination, fatigue, even clinical conditions like myasthenia gravis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. If you want to decode how force, speed, and precision come together in movement you start here.

The Core Components of a Motor Unit

The Alpha Motor Neuron: The Command Center

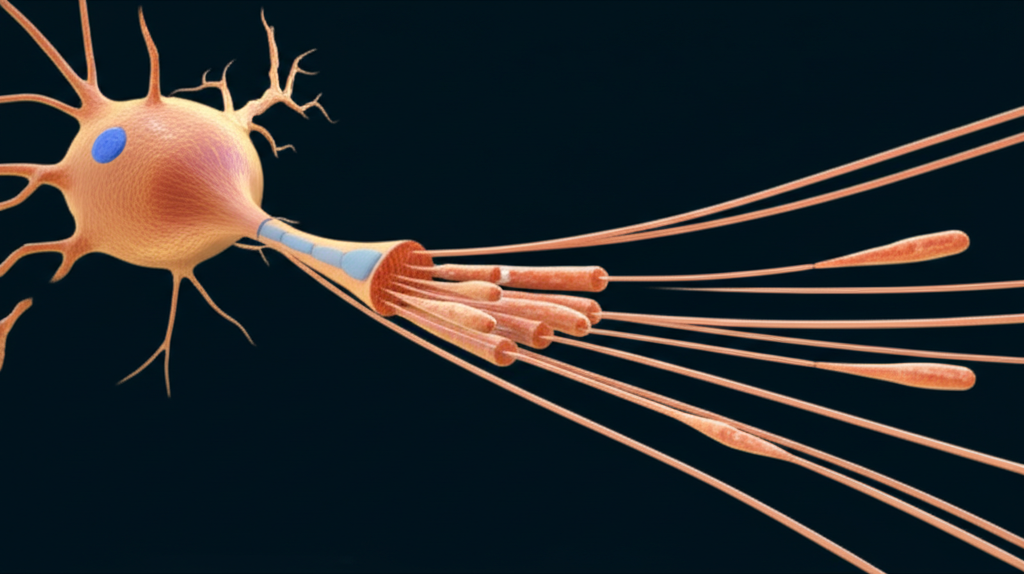

When I picture a motor unit I start with the alpha motor neuron. Its cell body (soma) sits in the spinal cord or brainstem. Dendrites branch like trees to receive inputs from the brain and spinal circuits. An axon runs from the spinal cord through the peripheral nervous system to the target skeletal muscle. That single axon branches near the muscle and connects to many individual muscle fibers. All those fibers belong to the same motor unit.

Alpha motor neurons are the final common pathway for voluntary muscle contraction. Signals move from the central nervous system (CNS) down descending tracts to these lower motor neurons. Upper motor neurons in the motor cortex send commands through the pyramidal tract for direct control. Other brain regions like the basal ganglia and cerebellum shape timing and coordination through extrapyramidal pathways. Those descending inputs converge on the motor neuron pool for each muscle, which is the group of alpha motor neurons that innervate that specific muscle.

The Muscle Fibers: The Responding Team

Every motor unit connects to a set of muscle fibers, and all fibers in a single motor unit share the same fiber type. If you stimulate the motor neuron the entire unit responds together. Fast or slow, oxidative or glycolytic, the fibers match.

The fibers themselves are long cells with a plasma membrane called the sarcolemma. Inside, you find myofibrils that house sarcomeres, the contractile units made of actin and myosin. Proteins like troponin and tropomyosin regulate how these filaments interact. The sarcoplasmic reticulum stores calcium and the T-tubules carry the electrical signal deep into the fiber. ATP powers the cross-bridge cycle, which is where actin and myosin slide past each other to shorten the muscle.

The Neuromuscular Junction: The Communication Bridge

The neuromuscular junction (NMJ) ties it together. This specialized synapse sits between the presynaptic terminal of the motor neuron and the postsynaptic membrane on the muscle fiber. The cleft between them is tiny, yet it’s where the magic happens.

When an action potential reaches the axon terminal, voltage-gated channels open and calcium ions flood in. That triggers synaptic vesicles to release acetylcholine (ACh) into the synaptic cleft. ACh binds to receptors on the motor end plate of the muscle. Sodium ions rush in and potassium ions flow out. If the end plate potential crosses threshold the muscle fiber fires its own action potential. Acetylcholinesterase in the cleft breaks down ACh to help reset the system for the next signal.

How a Motor Unit Works: From Signal to Contraction

From Action Potential to Muscle Shortening

Here’s the flow I walk through when I teach this.

- Initiation: An action potential travels along the alpha motor neuron’s axon to the NMJ.

- Synaptic Transmission: Calcium enters the presynaptic terminal and triggers ACh release. ACh crosses the synaptic cleft and binds to the motor end plate on the sarcolemma.

- Muscle Fiber Excitation: The muscle fiber reaches threshold and generates its own action potential. That signal travels along the sarcolemma and dives through T-tubules.

- Excitation-Contraction Coupling: The action potential triggers the sarcoplasmic reticulum to release calcium. Calcium binds to troponin and shifts tropomyosin off actin’s binding sites. Myosin heads bind to actin, ATP fuels the power stroke, and the sarcomere shortens. That is contraction.

- Relaxation: Calcium pumps clear Ca2+ back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Tropomyosin covers binding sites again. The fiber relaxes.

The All-or-None Principle

A single muscle fiber acts like a light switch. It either fires a full action potential or it doesn’t. There’s no half action potential. That is the all-or-none principle at the fiber level. The nervous system still grades muscle force very smoothly because it recruits different numbers and types of motor units and it changes how fast the active units fire. That mix gives you everything from a soft touch to a crushing grip.

Types of Motor Units and Their Roles

Slow, Fast Fatigue-Resistant, and Fast Fatigable

I usually sort motor units into three functional types because it explains so much about performance and fatigue.

- Slow-Twitch (Type S / Type I):

- Fibers: Slow-oxidative

- Contraction speed: Slow

- Fatigue resistance: High

- Force: Low

- Typical firing rate: about 10–20 Hz

- Best for: posture and endurance work like standing or easy cycling

- Fast-Twitch Fatigue-Resistant (Type FR / Type IIa):

- Fibers: Fast-oxidative glycolytic

- Contraction speed: Fast

- Fatigue resistance: Moderate

- Force: Intermediate

- Typical firing rate: about 20–50 Hz

- Best for: steady power like walking uphill or sustained breathing with the diaphragm

- Fast-Twitch Fatigable (Type FF / Type IIx):

- Fibers: Fast-glycolytic

- Contraction speed: Very fast

- Fatigue resistance: Low

- Force: High

- Typical firing rate: about 50–100+ Hz

- Best for: short, explosive efforts like sprinting or jumping

These types map cleanly to how you feel during exercise. You can hold a plank for a while because Type I units hang in there. You can sprint hard for only a few seconds because Type IIx units gas out fast.

Innervation Ratio: Precision vs Power

The innervation ratio is the number of muscle fibers supplied by one motor neuron. Small ratios give precision. Large ratios give power.

- Extraocular muscles can be roughly 1:5 to 1:10. One neuron controls five to ten fibers. That’s why your eyes can make tiny, precise movements.

- Laryngeal muscles can be as fine as about 1:2 to 1:3. Speech requires delicate control.

- Fingers vary. Some small hand muscles can be around 1:100. You get both finesse and meaningful force.

- The gastrocnemius can hit 1:1000 to 1:2000. You get big force for push-off.

- Vastus lateralis in the thigh can sit near 1:1500 to 1:2000. Great for strong knee extension.

Small motor units rule fine motor control. Large motor units make heavy work possible.

Motor Unit Recruitment: Henneman’s Size Principle

When I learned Henneman’s Size Principle I finally understood how the body keeps movement smooth. The nervous system recruits motor units in an orderly way based on the size of the motor neuron. Small units with low thresholds fire first. They are usually slow Type I units. As force demands climb, the system adds larger Type IIa units. When you need max force, it brings in the big Type IIx units.

That sequence matters. It keeps energy use efficient and it avoids overkill. You wouldn’t use a sledgehammer to tap a nail. Your nervous system does the same with muscle force. It starts small and scales up only when needed.

Rate Coding, Summation, and Tetanus

Recruitment picks which motor units fire. Rate coding decides how fast they fire. Increase the firing frequency and you get more force from those active units because the twitches begin to summate. If the frequency gets high enough the individual twitches fuse into a smooth tetanic contraction. That doesn’t mean the muscle is in disease states like tetanus. It just means you have a steady high-frequency firing pattern that keeps the muscle shortened.

Together, recruitment and rate coding give you graded muscle contractions. You can hold a cup without crushing it because the nervous system is brilliant at this.

Sensory Feedback and Control

Muscle Spindles and Golgi Tendon Organs

Movement isn’t just output. Sensory feedback keeps it accurate.

- Muscle spindles sit in parallel with muscle fibers and sense stretch and changes in length. They drive stretch reflexes that help maintain muscle tone and stability.

- Golgi tendon organs sit in series with the muscle at the tendon and sense tension. They can inhibit the motor neuron pool when tension gets too high to protect against injury.

I lean on these sensors when I explain balance and posture. Stand on one foot and you can feel micro-adjustments that keep you upright. Spindles and Golgi tendon organs help the system react in real time.

Motor Neuron Pools and CNS Control

Every skeletal muscle has a motor neuron pool in the spinal cord. Descending commands from the motor cortex, brainstem, and cerebellum land there. Control flows through multiple tracts.

- Pyramidal tract (corticospinal): fine voluntary movement

- Extrapyramidal tracts: posture and coordinated motion

- Basal ganglia: action selection and initiation

- Cerebellum: error correction and timing

Upper motor neuron lesions change reflexes and tone. Lower motor neuron lesions reduce reflexes, cause fasciculations, and lead to muscle atrophy. You can tell a lot about where a problem sits by watching motor unit behavior during simple tasks.

Clinical Significance: Health, Disease, and Assessment

EMG Basics and What It Shows

Electromyography (EMG) gives you a window into motor units. When I first watched a live EMG trace it felt like seeing movement in code. You can record motor unit potentials (MUPs) and learn a lot.

- In healthy muscle, MUPs are often biphasic or triphasic.

- Typical duration sits around 5–15 ms.

- Amplitude can range from roughly 100 µV to 3 mV.

- Patterns change with recruitment and firing frequency.

Neurogenic conditions like ALS or old poliomyelitis often show larger, longer, more polyphasic potentials. That happens because surviving motor neurons sprout new branches to reinnervate orphaned fibers. You see fewer units that each control more fibers. Myopathic conditions like muscular dystrophy often show small, short MUPs because individual fibers within motor units are lost or weakened. EMG doesn’t diagnose every condition on its own yet it pairs well with clinical exams and other tests.

Neuromuscular Disorders That Impact Motor Units

I use motor units as the lens when I explain common disorders.

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Progressive degeneration of motor neurons. Units drop out. Remaining neurons may show collateral sprouting for a time. Weakness and atrophy follow as the pool shrinks.

- Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA): Genetic loss of lower motor neurons. Fewer units from the start. Profound weakness can occur.

- Myasthenia Gravis: Autoimmune attack on acetylcholine receptors at the NMJ. Transmission becomes unreliable. You see fatigable weakness that improves with rest because the NMJ needs to reset.

- Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome: Antibodies target presynaptic calcium channels. ACh release falls. With repetitive activity, calcium can build up and briefly improve strength. That pattern helps distinguish it from myasthenia gravis.

- Botulism: Toxin blocks ACh release at the presynaptic terminal. Flaccid paralysis follows.

- Tetanus (disease): Toxin blocks inhibitory interneurons in the CNS. Unchecked motor neuron firing causes painful spasms and rigidity.

- Poliomyelitis: Viral damage to motor neurons. Reinnervation and axonal sprouting can remodel surviving units, which EMG can reveal years later.

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome: Immune attack on peripheral nerves. Conduction slows or blocks. Weakness and areflexia appear.

- Peripheral Neuropathies: Diabetes, toxins, or compression can injure axons. Units shrink or remodel.

You can map each condition to a specific problem in the chain. The alpha motor neuron can fail. The NMJ can fail. The muscle fiber can fail. The motor unit concept makes those links concrete.

Aging, Exercise, and Motor Unit Adaptation

Strength, Hypertrophy, and Motor Learning

Aging changes motor units. Estimates suggest a gradual loss of motor units begins in later decades of life. Loss rates can sit near 0.5–1% per year after about age 60–70 in some muscles. Fewer motor units mean less maximal force and a higher share of large, less precise units due to reinnervation. That shift contributes to sarcopenia, which is age-related declines in muscle mass and strength.

Good news. Exercise helps. Strength training boosts force through neural adaptations first. You get better recruitment and better rate coding. That improvement shows up before muscle hypertrophy kicks in. Over time, fibers grow and force rises further. Motor learning principles shape this process. Practice builds efficient patterns through neuroplasticity in the motor system. You move with fewer errors and more economy.

Endurance training builds oxidative capacity and fatigue resistance. You recruit Type I units often and you increase capillary density and mitochondrial function. You also improve coordination between agonists and antagonists. You save energy because muscles stop fighting each other.

Reinnervation, Axonal Sprouting, and Remodeling

When motor neurons die the nervous system tries to patch the gap. Surviving neurons can sprout new axon branches to reinnervate denervated fibers. That reinnervation increases the size of individual motor units. It preserves some function yet it reduces fine control because each unit now covers more fibers. You see this in aging and after nerve injury.

This remodeling is part of neuroplasticity. Rehabilitation therapy uses it. Physical therapy and occupational therapy harness repetition, task specificity, and progression to encourage useful plastic changes. Biofeedback can help a person learn to recruit units more effectively. EMG biofeedback makes those hidden patterns visible so the brain can adjust.

Special Cases: Fine Control and Breathing

Eye and Hand Muscles

I never tire of using eye muscles as a precision example. Extraocular motor units are tiny with very low innervation ratios. When you scan a page your eyes make minuscule adjustments at high speed. That level of fine motor control depends on small, fast units and tight central control.

Hands sit in the middle. You need finesse for handwriting and enough force for grip. The nervous system recruits small motor units for precision tasks like threading a needle. It brings in larger units for opening a jar. The same muscle can do both because it contains a mixture of motor unit types and the system picks what the task needs.

Diaphragm and Respiratory Motor Units

The diaphragm is a marvel. It must contract rhythmically for life. You sleep, you speak, you sprint, and it adapts on the fly. Many diaphragm motor units look like Type FR. They are fatigue-resistant enough for continuous work yet fast enough to increase ventilation when you exercise. Motor neurons to the diaphragm sit in the cervical spinal cord and run through the phrenic nerve. Failures in this pathway can threaten breathing which is why neuromuscular diseases that involve respiratory motor units are so serious.

Practical Tips for Students, Coaches, and Clinicians

- Define it first. A motor unit is a single alpha motor neuron plus all the muscle fibers it innervates.

- Visualize the chain. Motor cortex to spinal cord to motor neuron pool to axon to NMJ to fiber. If any link fails the unit fails.

- Think in types and ratios. Type S vs Type FR vs Type FF units explain endurance vs power. Innervation ratio explains precision vs force.

- Use Henneman’s principle every day. Start small and add more. That’s how you organize progressive overload in training. That’s how you cue graded activation in rehab.

- Watch fatigue patterns. Type IIx units blow up fast and fade fast. Type I units keep going. Program and pace with that in mind.

- Use EMG wisely. It shows recruitment, rate coding, and motor unit potential features. It pairs best with a careful exam and task-based observation.

- Build tolerance and skill. Endurance work targets oxidative fibers and steady recruitment. Strength work raises neural drive and hypertrophy. Motor learning underpins both.

A Quick Analogy to Electric Motors

I often compare biological motor units to parts of an electric motor because it helps people picture the system. The analogy is not perfect yet it lands for most beginners.

- A motor unit’s alpha motor neuron is like a controller that drives current to a device. The unit’s muscle fibers are the working element that converts the command into motion.

- The brain picks how many units to fire and how fast they fire just as a control circuit decides how much current to send to a motor.

- Small units feel like fine control modes. Large units feel like high-torque modes.

If you like engineering metaphors, reading a quick overview of a basic electric motor principle can make the rhyme between control and output clearer. The same for seeing how a stator and rotor share work in a machine. When I troubleshoot neuromuscular issues I sometimes borrow the mindset from engineering diagnostics because it keeps me systematic. Step through inputs, connections, and outputs. That process feels similar to working through a motor problem checklist. In biology you just swap soldering irons for reflex hammers and EMG needles.

Conclusion: The Orchestration Behind Every Movement

I like to end where I began. The motor unit is the smallest functional unit of muscle contraction, and it’s the right scale for understanding human movement. One alpha motor neuron and all the muscle fibers it innervates. A neuromuscular junction that passes the message. A cascade inside the fiber that turns an electrical impulse into mechanical force.

Once you see how motor units differ by type and size you can explain endurance and power. Once you grasp Henneman’s Size Principle you can explain smooth control. Once you pair this with sensory feedback you can explain coordination, tone, and reflexes. And when you follow the chain from cortex to muscle you can pinpoint how diseases and injuries create weakness or fatigue.

Every walk, breath, and handshake is an orchestration of motor units. The show runs quietly in the background. You only notice when something slips. Learn the parts. Learn the sequence. You will read every movement in a new way.

Final self-check on internal links:

- motor principle: used once

- stator and rotor: used once

- motor problem: used once

Total internal links: 3 (between 3 and 5). No URL repeated.