When to Choose a Wound Rotor Induction Motor: Key Applications & Benefits

Of course, here is the comprehensive, long-form article based on your instructions.

Table of Contents

- The Heavy Lifter: Needing Insanely High Starting Torque

- The Gentle Giant: When You Must Limit Starting Current

- The Original Speed Controller: When You Need Adjustable Speed Without a VFD

- Material Handling: The Art of the Smooth Lift

- Mining & Aggregates: Taming the Toughest Loads

- Cement, Sugar & Heavy Processing: Powering Through Inertia

- Pumps & Fans: A Controlled Start for Big Air and Fluid Movers

- Unmatched Starting Performance

- Smooth as Silk Acceleration

- Built Tough: Robustness and Simplicity

- Useful Speed Control Capability

- WRIM vs. the Standard Squirrel Cage Motor (SCIM)

- WRIM vs. the Precision of a DC Motor

- The Elephant in the Room: WRIMs vs. Modern VFDs

Introduction: Meeting the Unsung Hero of Heavy Industry

If you’ve spent any time in heavy industrial settings—think sprawling cement plants, noisy mining operations, or towering port cranes—you’ve probably walked right past one without even realizing it. I’m talking about the wound rotor induction motor, or WRIM for short. For years, I saw them as just another type of motor, a bit of an old-school relic. But a few tough projects taught me that these motors aren’t relics; they’re specialists. They are the problem-solvers you call in when the standard, everyday motor just can’t cut it.

So, what exactly sets a WRIM apart?

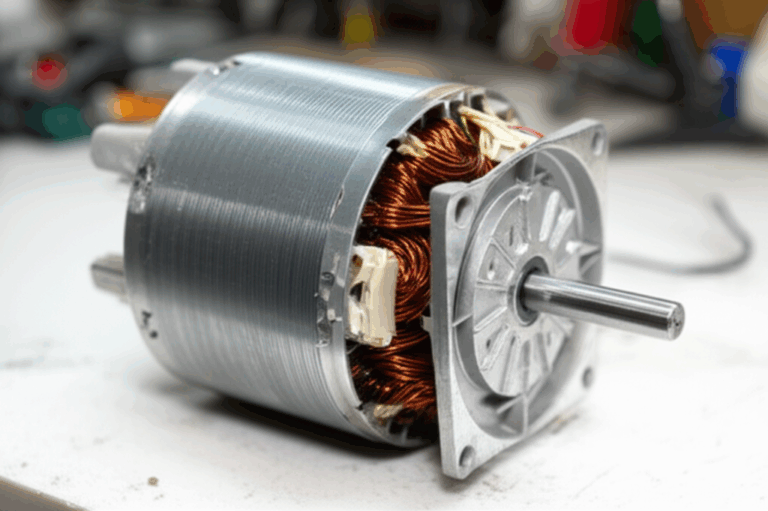

Unlike the more common squirrel cage induction motor, which has a simple, rugged rotor, the WRIM has a more complex one. Its rotor has windings, much like the stationary part of the motor, the stator. These windings are connected through slip rings and brushes to an external control panel, usually a bank of resistors. This one difference—the ability to connect to the rotor from the outside—is its superpower. It allows you to fundamentally change the motor’s performance characteristics during startup and operation.

Think of it this way: a standard squirrel cage motor is like a car with an automatic transmission that only has one gear. It’s simple, reliable, and great for cruising on the highway. A wound rotor motor, on the other hand, is like a heavy-duty truck with a manual transmission and a clutch. It gives you incredible control right when you need it most—when you’re starting from a dead stop with a massive load hitched to the back.

Over the years, I’ve learned that choosing a WRIM isn’t about picking the newest technology. It’s about strategically picking the right technology for a specific, demanding job. Let’s dive into exactly when and why you’d make that choice.

The Big Three: When a Wound Rotor Motor Becomes Your Best Friend

In my experience, the decision to use a wound rotor induction motor almost always comes down to solving one of three core problems. If you’re facing any of these, a WRIM should be high on your list of potential solutions.

The Heavy Lifter: Needing Insanely High Starting Torque

I’ll never forget a project at a rock quarry. They had a massive crusher that was an absolute beast to get moving. A standard motor would either trip the breaker or just sit there and hum, unable to overcome the immense static friction and inertia of the loaded machine. This is the classic scenario for a WRIM.

Because you can add external resistance to the rotor circuit, you can manipulate the motor’s torque-speed curve. This lets you generate maximum torque right at zero speed. We’re talking about starting torque that can reach 250% or even 300% of the motor’s full-load rating. This is essential for applications involving:

- Large Inertia Loads: Think of things that are incredibly heavy and take a long time to get up to speed, like grinding mills in a cement plant, large industrial fans, or flywheels. You need a sustained, powerful push to get them going.

- Starting Under Load: A conveyor belt loaded with tons of ore or a crane lifting a heavy container can’t afford a weak start. The motor needs to deliver powerful torque from the very first moment.

- High Static Friction: Some machines, due to their design or the materials they process, have a huge amount of “stickiness” to overcome. A WRIM provides that initial breakaway force without breaking a sweat.

A standard squirrel cage motor struggles here. Its starting torque is fixed by its design and is often much lower, which is fine for a simple pump or fan, but not for these heavy-duty industrial motors.

The Gentle Giant: When You Must Limit Starting Current

The second major reason I’ve turned to WRIMs is to be kind to the electrical grid. A large standard induction motor starting up is like flushing every toilet in a skyscraper at once—it puts a huge, sudden demand on the system. This massive inrush of current (often 5 to 7 times the motor’s normal running current) can cause serious problems:

- Voltage Sag: You’ve seen this at home when the AC kicks on and the lights dim for a second. Now imagine that on a factory-wide scale. This voltage dip can cause sensitive electronics to trip, affect other running machinery, and create instability.

- Utility Penalties: Power companies don’t like these huge current spikes. In many areas, they’ll hit you with hefty “demand charges” if your facility draws too much power too quickly.

- Weak Grids: In remote locations, like a mine or a rural processing plant, the power grid might not be robust enough to handle a massive inrush current. The WRIM is a network-friendly motor solution.

By inserting resistance into the rotor circuit at startup, a WRIM can dramatically lower its starting current, often to just 1.5 to 2.5 times its full-load current. It’s a “soft start” that’s built right into the motor’s design. As the motor gains speed, you gradually remove the resistance in steps, allowing for a smooth, controlled ramp-up that doesn’t shock the power system. It’s an incredibly effective method for motor starting current reduction.

The Original Speed Controller: When You Need Adjustable Speed Without a VFD

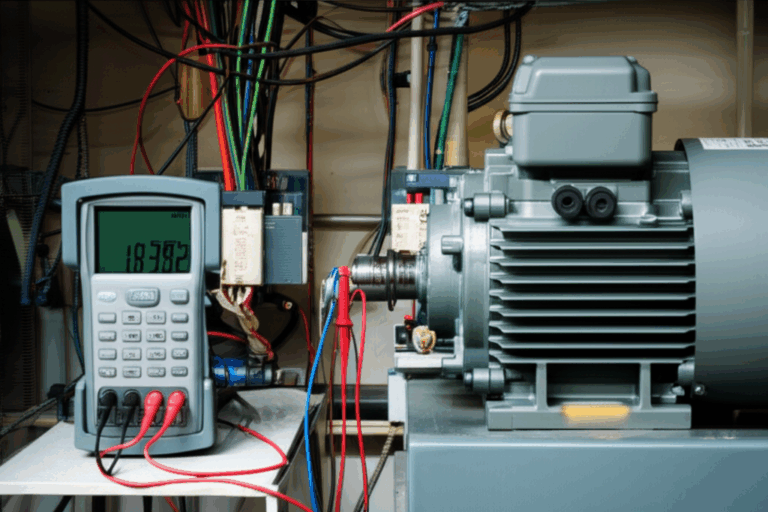

Before Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs) became the go-to for speed control, the WRIM was king. By leaving some resistance in the rotor circuit during operation, you can make the motor “slip” more, effectively reducing its speed. While it’s not as precise or efficient as a VFD, this method of speed regulation in a WRIM is simple, robust, and incredibly effective for certain jobs.

This is particularly useful in applications where you need limited speed adjustment, maybe between 50% and 90% of full speed. Think of:

- Cranes and Hoists: You need to lift a heavy load quickly but then slow down for precise placement. A WRIM allows for this fine speed control at start and during the lift.

- Conveyors: Adjusting the speed of a conveyor belt to match the process throughput.

- Pumps and Fans: Making moderate adjustments to flow rates without the complexity of an electronic drive.

In environments that are extremely hot, dusty, or prone to electrical noise, the simplicity of a resistor bank can be more reliable than a sensitive VFD. While VFDs are amazing, sometimes a tougher, simpler solution is the right call. The fundamental principles behind how a motor works are key here; understanding the motor principle helps clarify why this external control is so powerful.

Where I’ve Seen WRIMs in Action: Real-World Industry Applications

Theory is great, but seeing where these motors pull their weight is what really drives the point home. I’ve specified or worked on WRIMs in some of the toughest environments out there.

Material Handling: The Art of the Smooth Lift

Nowhere is the smooth control of a WRIM more apparent than in cranes, hoists, and elevators. When you’re lifting a multi-ton load, the last thing you want is a jerky, uncontrolled start. This puts immense mechanical stress on cables, gears, and the structure itself. WRIMs provide that smooth acceleration, gradually applying torque to lift the load without shock. This controlled start-up is vital for both safety and equipment longevity.

Mining & Aggregates: Taming the Toughest Loads

Mining is brutal on equipment. Crushers and grinding mills are classic examples of high inertia, high shock load applications. A WRIM is perfect for this. It can provide the massive starting torque needed to get a mill full of rock turning and can absorb the shock loads that come with a large, uncrushed boulder entering the system. The robust design of these motors for harsh environments makes them a reliable choice deep in a mine or in a dusty quarry. Mine hoists, which carry people and materials deep underground, also rely on the controlled acceleration and braking that WRIMs offer.

Cement, Sugar & Heavy Processing: Powering Through Inertia

I once worked on a commissioning for a cement mill drive. The sheer scale of the equipment was mind-boggling. These massive, rotating kilns and ball mills are the definition of high inertia loads. A WRIM allows these giants to be started slowly and gently, without putting excessive strain on the gears or the power grid. Similarly, in the sugar industry, large cane shredders and crushers use WRIMs to handle the heavy, intermittent loads as cane is fed into the mill.

Pumps & Fans: A Controlled Start for Big Air and Fluid Movers

For very large industrial pumping applications or large fan drives, starting can be an issue. A direct-on-line start can cause “water hammer” in pipes or put huge stress on fan blades and ducts. A WRIM, with its soft-starting capability, can gently bring these systems up to speed, protecting the mechanical components and the electrical network. While VFDs are very common here now, in some cases, a WRIM is still chosen for its simplicity and robustness, especially in retrofitting old motors where the infrastructure for a VFD might be complex to install.

Breaking It Down: The Key Advantages I Always Come Back To

When I’m explaining to a project manager why we should consider a WRIM, I usually boil it down to four key benefits that directly address the problems we’ve discussed.

Unmatched Starting Performance

This is the headline feature. You get the best of both worlds: incredibly high starting torque combined with remarkably low starting current. No other AC motor type can achieve this without the help of an external electronic drive. This is why it’s the go-to solution for heavy inertia applications.

Smooth as Silk Acceleration

By staging the removal of the external resistance, you get a stepped but very smooth acceleration profile. This gentle ramp-up reduces mechanical shock on everything connected to the motor—gearboxes, couplings, belts, and the load itself. This directly translates to less wear and tear and a longer life for your entire system.

Built Tough: Robustness and Simplicity

The motor itself is a simple, rugged piece of machinery. The control system—a bank of resistors—is also fundamentally simple and durable. In dirty, hot, or vibrating environments where complex electronics might fail, a WRIM system often proves more reliable. The maintenance of slip ring motors is higher due to the brushes, but it’s a straightforward mechanical task, not a complex electronic troubleshooting one. The core of the motor, with its durable stator core lamination, is built to last for decades in tough conditions.

Useful Speed Control Capability

While not as versatile as a VFD, the ability to control speed by about 20-40% is incredibly useful for process control in many applications. It provides a level of adjustability that a standard SCIM just can’t offer on its own.

The Big Showdown: WRIMs vs. The Alternatives

A WRIM doesn’t exist in a vacuum. To truly understand its place, you have to compare it to the other players on the field. The choice often comes down to a detailed analysis of performance, cost, and maintenance.

WRIM vs. the Standard Squirrel Cage Motor (SCIM)

This is the most common comparison. A SCIM is cheaper, simpler, and requires almost no maintenance because it lacks brushes and slip rings. For any constant-speed application with low to moderate starting torque needs, a SCIM is almost always the right choice. It’s the workhorse of the industry for a reason.

You choose a WRIM only when the SCIM’s fixed starting characteristics (high current, lower torque) are a deal-breaker for your application.

WRIM vs. the Precision of a DC Motor

Historically, if you needed precise speed control and high torque, you used a DC motor. They offer fantastic performance, especially at very low and zero speeds. However, they require a DC power supply and have commutators and brushes that need significant maintenance. I’ve found that for most heavy industrial AC applications, a WRIM offers a more practical, lower-maintenance solution unless that ultra-precise, full-torque-at-zero-speed capability is an absolute must.

The Elephant in the Room: WRIMs vs. Modern VFDs

This is the big one. The rise of the VFD has, without a doubt, reduced the number of new applications for WRIMs. A modern VFD paired with a standard (and cheaper) squirrel cage motor can do almost everything a WRIM can do, and often better. A VFD can provide:

- Full torque at zero speed.

- Extremely low starting current.

- Precise speed control across the entire range (0-100%+).

- Higher overall system efficiency, especially at reduced speeds.

So, is the WRIM obsolete? Not at all. I still find myself specifying them in a few key niches. The choice becomes strategic when you consider the total cost of ownership and the operational environment. When diagnosing issues, understanding the interaction between the stationary and moving parts is critical, as a problem with the stator and rotor can mimic other failures.

WRIMs retain their value when:

- The Environment is Brutal: In extremely hot, dusty, or vibration-prone locations, the simple resistor bank of a WRIM can be more reliable than a complex VFD packed with sensitive electronics.

- The Power Grid is Unclean: VFDs can sometimes be sensitive to poor power quality, whereas a WRIM system is generally more tolerant.

- Simplicity is Paramount: For staff in a remote location, troubleshooting a resistor bank is often far easier than diagnosing a fault in a complex VFD.

- Cost for a Specific Niche: For a large, high-power application that only needs a soft start and no ongoing speed control, a WRIM with a starting resistor might actually be cheaper than a comparably rated VFD.

Conclusion: It’s Not Obsolete, It’s a Specialist

So, when is a wound rotor induction motor to be used?

My journey with these machines has taught me to see them not as an old technology, but as a highly specialized tool. You don’t use a sledgehammer to hang a picture frame, and you don’t use a standard motor to start a multi-thousand-ton grinding mill.

You turn to a WRIM when you’re backed into a corner by the laws of physics and electricity. You use it when your load demands immense starting torque, when your power grid begs for a gentle start, or when you need simple, robust speed control in an environment that would chew up and spit out more delicate electronics. The balance of its internal components, including the precisely manufactured rotor core lamination, gives it this unique capability.

While the VFD has rightly taken over as the master of variable speed, the wound rotor motor remains the undisputed, old-school champion of the tough start. It’s a testament to solid, fundamental electrical engineering, and in the right application, it’s still the best solution for the job.