Why Are They Called Eddy Currents? Unraveling the Name Behind the Phenomenon

As an engineer or designer, you’re constantly balancing performance, efficiency, and cost. Every decision, down to the very materials in a motor core, has a ripple effect on the final product. You’ve likely encountered the term “eddy currents,” often in the context of core losses and inefficiency. But have you ever stopped to ask why they have such a peculiar name? Understanding the origin of the term isn’t just a matter of trivia; it provides a powerful mental model for grasping what these currents are, why they cause problems, and how we can harness them for our benefit.

If you’ve ever found yourself puzzling over the physics of motor core losses or trying to visualize what’s happening inside a transformer, you’re in the right place. This guide will unravel the story behind the name “eddy currents,” connecting a simple, intuitive analogy to the deep engineering principles that govern the efficiency of your designs.

In This Article

- The Core Question: What’s in a Name?

- Visualizing the “Eddy”: An Analogy from Fluid Dynamics

- The Discovery and Naming: A Glimpse into History

- How Eddy Currents Form: The Physics Behind the Swirl

- Characteristics That Solidify the Name

- Beyond the Name: Why Eddy Currents Matter in Your Work

- Your Engineering Takeaway: A Name That Perfectly Describes a Phenomenon

The Core Question: What’s in a Name?

So, why are they called eddy currents?

The short answer is that they are named for their striking resemblance to eddies in a fluid, like water or air.

When you see a river flowing smoothly and it suddenly encounters a rock or a bridge piling, the water’s flow is disrupted. It can’t just stop; instead, it swirls around the obstacle, forming small, localized whirlpools. These swirling patterns of movement are called eddies. They represent a chaotic, circulating flow that breaks away from the main, uniform current.

In the 19th century, when physicists first observed the strange electrical currents induced inside solid blocks of metal, they needed a way to describe them. They noticed that these currents didn’t flow in a straight line from point A to point B. Instead, they formed closed loops, swirling and circulating entirely within the conductive material. The visual and behavioral parallel to water eddies was so perfect that the name stuck. It was an intuitive, descriptive term for a complex electromagnetic phenomenon.

Visualizing the “Eddy”: An Analogy from Fluid Dynamics

To truly appreciate the name, let’s deepen the analogy. Thinking like a 19th-century physicist can make this abstract concept concrete.

Eddies in Water: A Familiar Picture

Imagine a wide, calm river. Its flow is laminar—smooth and predictable. Now, place a large boulder in its path. The water immediately behind the boulder forms swirling vortices. These are eddies. Key characteristics include:

- Circular Paths: They move in closed loops, separate from the main flow.

- Energy Dissipation: These whirlpools contain kinetic energy, but it’s a chaotic energy that often dissipates as heat and sound, contributing nothing to the river’s overall progress downstream.

- Localized Nature: They exist within a specific area of the fluid where the flow is disturbed.

The Electromagnetic Parallel: Electrical Whirlpools

Now, let’s translate this to the world of electromagnetism. Instead of a river of water, picture a solid block of a conductor, like copper or aluminum. This block is filled with a “sea” of free electrons, ready to move if given a push.

The “boulder in the river” is a changing magnetic field.

According to Faraday’s Law of Induction, whenever you expose a conductor to a changing magnetic field, you induce an electromotive force (EMF), which is essentially a voltage. This EMF acts as a pressure that pushes on the sea of electrons, compelling them to move.

But where do they move? Since they are inside a solid block of metal, they can’t just flow out into the air. Instead, they begin to circulate within the conductor, forming closed loops of electrical current. These tiny, swirling electrical currents are the “eddies.”

Just like their fluid counterparts, these eddy currents have parallel characteristics:

- Circular Paths: They flow in closed loops within the conductive material.

- Energy Dissipation: As these currents swirl through the material’s natural electrical resistance, they generate heat through a process called Joule heating. This is a direct power loss, converting useful electrical energy into wasted thermal energy.

- Localized Nature: They are strongest where the change in the magnetic field is most significant.

This analogy isn’t just a convenient teaching tool; it’s the very reason the phenomenon got its name. It perfectly captures the visual of a circulating, energy-wasting current that emerges in response to an external disturbance.

The Discovery and Naming: A Glimpse into History

While the term “eddy current” is descriptive, the credit for first observing and documenting their effects goes to the brilliant French physicist Léon Foucault in 1855.

Leon Foucault’s Contribution

Foucault, who is perhaps more famous for his pendulum experiment demonstrating the Earth’s rotation, was also a master of experimental physics. In one famous experiment, he rotated a copper disc between the poles of a powerful electromagnet. He observed two fascinating things:

Foucault correctly deduced that the magnet’s field was inducing circulating currents within the rotating disc. These currents, in turn, generated their own magnetic fields that, according to Lenz’s Law, opposed the very motion that created them. This opposition produced the braking force. The heat was a direct result of these induced currents flowing through the copper’s resistance.

Because of his foundational work, eddy currents are still often referred to in academic and technical circles as “Foucault currents.” While “Foucault currents” is the historically precise term, “eddy currents” won out in common engineering language because of its powerful and intuitive descriptive nature. It simply does a better job of painting a picture of what’s happening inside the material.

How Eddy Currents Form: The Physics Behind the Swirl

Understanding the name and the analogy is the first step. For an engineer, knowing the underlying physics is crucial for designing systems that either mitigate or utilize this effect. The formation of eddy currents is a beautiful interplay of fundamental electromagnetic laws.

1. Changing Magnetic Fields are Key (Faraday’s Law of Induction)

The entire process begins with a change in magnetic flux. Magnetic flux is a measure of the total magnetic field lines passing through a given area. You can change this flux in two primary ways:

- Move a conductor through a stationary magnetic field (like Foucault’s rotating copper disc).

- Expose a stationary conductor to a time-varying magnetic field (like the core of an AC transformer).

Faraday’s Law of Induction states that any change in the magnetic flux through a conducting loop will induce an electromotive force (EMF), or voltage, in that loop. The faster the magnetic field changes, the greater the induced EMF.

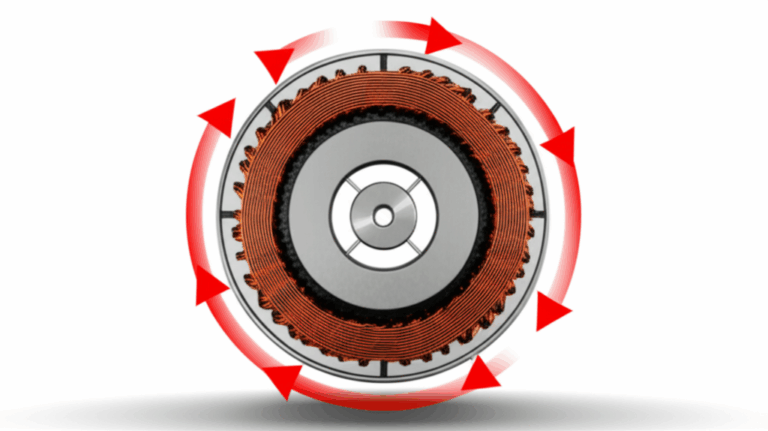

2. The Conductor’s Response

This induced EMF acts on the free electrons within the conductor. In a solid piece of metal, these electrons are now driven to flow. Because the conductor is a bulk material, the electrons don’t follow a single wire path. Instead, they take the path of least resistance, which results in them forming broad, circulating planes of current—the eddies.

The size and strength of these eddy currents depend on several factors:

- Strength of the Magnetic Field: A stronger field induces stronger currents.

- Rate of Change: Higher frequencies of AC or faster motion result in much stronger currents.

- Material’s Resistivity: Materials with low resistivity (like copper and aluminum) allow large eddy currents to form easily. Higher resistivity materials (like ferrites or silicon steel) resist the flow, reducing the currents.

- Geometry of the Conductor: A solid block of metal provides a large, uninterrupted area for huge eddies to form.

3. The Opposing Force (Lenz’s Law in Action)

This is where the magic happens. An electric current always produces its own magnetic field. According to Lenz’s Law, the magnetic field created by the induced eddy current will always be in a direction that opposes the original change in magnetic flux that created it.

Think of it as nature’s inertia for magnetism. If you try to increase the magnetic field through a conductor, the eddy currents will create a field pointing in the opposite direction to fight your increase. If you try to decrease the field, the eddy currents will create a field pointing in the same direction to try and prop it up.

This opposition is the source of the braking or damping effect. The interaction between the original magnetic field and the one produced by the eddy currents creates a repulsive or attractive force (a Lorentz force) that resists motion and dissipates energy.

Characteristics That Solidify the Name

The name “eddy current” is reinforced by the observable effects it produces, all of which stem from its circulating, energy-dissipating nature.

- Circular Paths: As discussed, this is the direct visual link to the name. Visualizing these swirling paths is key to understanding how mitigation techniques, like laminations, work by breaking up these paths.

- Resistive Heating (Joule Heating): Every conductor has some electrical resistance. As the eddy currents flow, they encounter this resistance and lose energy, which is released as heat. The power lost to heat is proportional to the square of the current (P = I²R). This is the primary cause of energy loss in transformers and motors and, conversely, the principle behind induction heating.

- Damping/Braking Effect: The opposing magnetic field generated by the eddy currents creates a force that resists the relative motion between the conductor and the magnetic field source. This effect is powerful enough to stop a high-speed train without any physical friction.

Beyond the Name: Why Eddy Currents Matter in Your Work

For engineers, eddy currents are not just a fascinating physical phenomenon; they are a critical design consideration with a dual personality. They can be a major source of inefficiency or a powerful tool, depending entirely on the application.

The Undesirable Effects: A Source of Loss and Heat

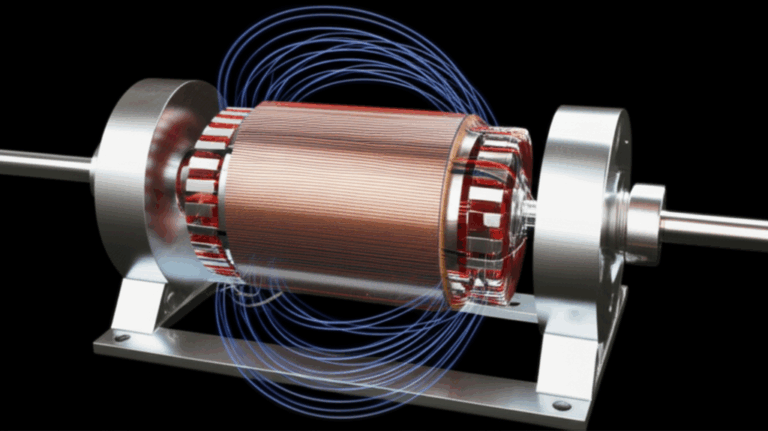

In most power conversion devices like transformers and electric motors, eddy currents are the enemy of efficiency. The AC magnetic fields that are essential for the operation of these devices inevitably induce eddy currents in the iron cores.

- Energy Loss in Transformers and Motors: The Joule heating caused by eddy currents is a direct loss of energy. This wasted energy doesn’t contribute to the motor’s torque or the transformer’s power transfer. It simply heats the device, which can lead to overheating, reduced component lifespan, and the need for larger cooling systems. The relationship between the key components, the stator and rotor, is fundamentally governed by magnetic fields, making core losses a central design challenge.

- How We Fight Back: Laminations: The single most effective strategy for minimizing eddy currents is to break up their flow paths. Instead of using a solid block of iron for a motor or transformer core, we construct it from a stack of very thin sheets of electrical steel, each coated with a thin insulating layer. These are laminations. The insulation prevents large currents from swirling across the entire core. Instead, only tiny, insignificant eddies can form within each thin sheet. By using thin silicon steel laminations, engineers can dramatically reduce these losses, often by 90% or more compared to a solid core. This principle is fundamental to the design of an efficient transformer lamination core.

The Beneficial Applications: Putting Eddies to Work

While we spend a lot of effort fighting eddy currents, clever engineering has turned this “problem” into a solution in many fields.

- Electromagnetic Braking: In high-speed trains, roller coasters, and heavy machinery, eddy current brakes provide smooth, powerful, and frictionless braking. A powerful electromagnet is lowered near a conductive rail or disc. The rapid motion induces massive eddy currents, which generate an opposing magnetic field and a strong braking force. There are no parts to wear out, making it incredibly reliable. The design of the rotor core lamination can even be optimized to enhance this braking effect in certain motor designs.

- Induction Heating: An induction cooktop uses a coil to generate a high-frequency alternating magnetic field. This field induces strong eddy currents directly in the base of a ferromagnetic pot or pan. The pan’s own electrical resistance causes it to heat up rapidly due to Joule heating, while the cooktop itself remains cool. This same principle is used in industrial furnaces to melt metals without direct contact.

- Metal Detectors: A metal detector works by transmitting a changing magnetic field from a search coil. When this field passes over a metal object, it induces eddy currents in the object. These currents generate their own weak magnetic field, which is then picked up by a second coil in the detector, signaling the presence of metal.

- Non-Destructive Testing (NDT): In aerospace and manufacturing, eddy current testing is used to find cracks and flaws in conductive materials. A probe induces eddy currents on the surface of a part. If there is a crack or defect, it disrupts the swirling path of the currents. This disruption is detected by the probe, revealing hidden flaws without damaging the component.

Your Engineering Takeaway: A Name That Perfectly Describes a Phenomenon

The name “eddy currents” is more than just a label; it’s a masterclass in scientific communication. It provides a powerful and intuitive analogy that instantly conveys the core nature of a complex electromagnetic effect.

Here’s what to remember:

- The Name is the Analogy: Eddy currents are named for their resemblance to the swirling, circular eddies that form in a fluid when its flow is disturbed.

- The Cause is Change: They are generated anytime a conductor is exposed to a changing magnetic field, as described by Faraday’s Law of Induction.

- The Effect is Opposition: The currents create their own magnetic field that opposes the change that created them (Lenz’s Law), leading to resistive heating and a damping force.

- A Dual Nature: In many applications like motors and transformers, these currents are parasitic losses that must be minimized, primarily through the use of thin, insulated laminations. In other applications, they are a powerful tool for braking, heating, and sensing.

The next time you are specifying the grade of electrical steel for a core or analyzing the efficiency of a motor design, remember the image of a simple whirlpool in a river. That swirling eddy is happening electrically inside your components, and understanding how to break it up—or in some cases, how to make it stronger—is fundamental to great engineering.

If you have questions about selecting the right lamination materials or manufacturing processes to manage eddy current losses in your specific application, a technical consultation can help clarify your options and optimize your design for peak performance and efficiency.